SPACE February 2025 (No. 687)

I AM AN ARCHITECT

‘I am an Architect’ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

interview Cha Jae principal, studio mmer × Kim Bokyoung

Along the Streamside

Kim Bokyoung (Kim): Your office is very nice. Is this office for your use alone?

Cha Jae (Cha): Instead of managing a large organisation and taking on unnecessary projects to sustain it, I prefer working alongside partners on projects that are meaningful. Instead, I manage a co-working space lounge called the ‘wet Segeomjeong’, where current and potential collaborators from the local community can freely use the space whenever required. I am currently curating the stories of wet Segeomjeong, while sharing the stage left and right as work spaces with Kim Daewoo, who planned and oversaw the overall operation of the Place Camp Jeju. The two pieces of furniture you see there have wheels. When turned, they can be used as a stand and therefore make the space versatile for lectures and performances.

Kim: How did you end up settling in this neighbourhood?

Cha: It has been a little over a year now since I first opened my office in this area. The most important factor for me when searching for the office site was whether the building was close to the natural environment with a large window that could frame it. I almost moved into an office right in front of Yangjaecheon Stream two years ago, but it didn’t go well. While searching for a new space, I came across this place. The fact that Hongjecheon Stream is right in front, with three windows of the office open to Inwangsan Mountain, Bukaksan Mountain, and Bukhansan Mountain, is a huge advantage.

Kim: You seem to have a preference for streamside locations.

Cha: That is true. Our previous office was in Euljiro. The area was good as the district was not sensitive to noise in the evenings and therefore I could have band practice rooms inside the office. However, Euljiro has its unique feeling of draining away one’s energy, and I realised that it wasn’t a place for me to stay and so decided to move on. This is why I ended up looking for a quiet riverside location where I could recharge. Now I think about it, I once had an office near Bulgwangcheon Stream as well!

Cha Jae

Models of milk cow in the studio mmer. studio mmer’s logo features the milk cow.

Architect Who Designs Scenes

Kim: studio mmer is not a typical architectural design firm. What is the nature of your work?

Cha: When launching this business, we introduced ourselves as ‘an agency for architecture, sound, visual design’, aiming to encompass various creative fields beyond architecture. Now we believe that we have moved on to our next stage, and therefore we are currently working on an overall restructuring and reconceptualisation, including that of our website. Quite different to that initial outline, we are now more focused on business strategy and operational consulting as much as spatial creativity with a keyword, ‘brand-space-experience-design’. Unlike the traditional architecture design, which does not directly deal with the contents, studio mmer aims to create spatial experiences by planning the contents itself. We place particular focus on creating brand experiences, developing brand strategies and assets, all of which takes precedence over spatial design, requiring strong consulting capabilities.

Kim: So within the broad framework of brand-space-experience design, you engage in a wide range of activities—from planning brand experiences for major corporations to working on local small businesses and brand urbanism projects for regional regeneration.

Cha: It seems like a broad working range if you categorise it that way. But, at its core, there is common ground in that everything starts by imagining the ‘scene’. Every project begins with the scene envisioned even before the start of building design. People may interpret this differently, but I consider the distinction between ‘scene’ and ‘scenery’ important. I define ‘scenery’ as elements like spatial proportions and materiality carefully framed compositions meant to be seen, and sensory-driven staging. Things like typical architectural photographs are considered to be ‘scenery’. These are spotless things that were shot at the perfect ‘magic hour’ with cameras positioned at the ideal angles. On the other hand, scenes capture the moment when the space is actually in use. Instead of the ‘magic hour’, it is a moment of ‘any hour’. A scene is about spontaneously dropping by at any time— not when everything is perfectly arranged, but when the space is bustling, lively, and full of everyday traces of use. It’s a cross-section of activity, capturing the raw, unfiltered energy of a place in motion.

Kim: Please tell us about your most memorable project.

Cha: The series of projects in Namhae remain the most memorable to me thus far. One night during a casual drinking session, a friend named Sugihara Yuta, who works on planning cultural projects between Korea and Japan, mentioned that he was organising a concert in Tokyo and invited me. Of course, it could have been just a friendly gesture but I am the type of person who follows up on such invitations. (laugh) So I ended up showing up to the show in Japan and having dinner together. Over dinner, Sugihara showed me a picture of the Namhae Dolchanggo Project, that he was helping out on in Korea. I was captivated by the shabby images of the Dolchanggo so much that I impulsively traveled to Namhae as soon as I returned to Korea. There I met the CEO of the Namhae Dolchanggo, Choi Seungyong and became friends, ultimately leading to my participation in an exhibition held at the Dolchanggo. Beyond that, I also initiated independent projects in Namhae. It was a project to transform a 40-year-old frozen storage facility into a cultural space called Space Mijo, where I worked on both content planning and spatial regeneration. Cultural spaces run by the public institution typically operate from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., aligned with the working hours of civil service workers. However, the most active time of the Mijohang Port is at 3 a.m., when fishing boats come and go, and fishermen start gathering catches. To ensure the space would be genuinely useful for the local community, I proposed a need for ‘Mijo 24’, a place that is brightly lit and sells lunch boxes, ramen, and fish baits at this time. In addition, I suggested creating a preparation space and system that could nurture people who would actually participate in these exhibitions, performances, and markets. This approach and project direction carried over into other projects like Anggang Pass and Namhaegak.

스튜디오 음머 내부 전경

It is Okay to be Spotted

Kim: The name studio mmer and the logo featuring a cow’s buttocks are quite striking.

Cha: studio mmer was the name I came up with during my years in school. It was meant to reflect a more every day, approachable architecture. Although I came into this field admiring ‘cool’ architecture, I became resistant to it after witnessing the obsession with the work of famous architects or of the often pretentious theoretical discourse that was prevalent in the field. Then one day, I came across Made in Tokyo (2001) by Atelier Bow- Wow in a library. It was a book on unique spaces that were informed by the need for spaces that suited the daily lives of those that would use them, not architects. Reading it I thought, ‘This is what real architecture is!’ I did not want to become an architect who just spoke in esoteric phrases that are totally disconnected from daily life. I decided that I’d rather engage with commercial architecture— the kind that many architects looked down on at the time. That’s where ‘mmer’ comes from—it derives from the word commercial. For my graduate thesis, I worked on a Korean version of Made in Tokyo. Commercial buildings in front of apartment complexes are covered in signs. Inside, you will find that the building is a mix of conflicting spaces, such as study rooms, tutoring centres, PC bangs, karaoke, billiard halls, all crammed together. I saw this chaotic but functional urban landscape as the true pattern of modern architecture. This was then linked to the image of a cow—how the white and black mix and make blotches, instead of turning grey.

Kim: Even if you were tired of the architecture of great architects, you could still have continued within the field of architectural design. Instead, you took interest in things that were ‘commercial’ or ‘popular’ and branched out into other areas.

Cha: I have always been interested in pop culture, even from my younger years. I played in a band since middle school. I had a desire to step further from just enjoying pop culture to creating it. One of my more minor reasons for starting out in architecture was the fact that musician Kim Dongryul from the band Exhibition, whom I admired as a boy, had studied architecture. Since I studied my undergrad and masters degree at Seoul National University’s school of architecture, and had my first job experience at SAC International, Ltd., most would have expected me to continue to pursue a career as an architect. After 7 – 8 years of work experience with mega projects at SAMOO A&E, I decided to work on small projects, making a bold decision to move to Japan without knowing a single letter of Japanese—this was a major turning point of my career. At that time, I developed connections with Korean IT professionals who had been sent to Japan on assignments, and through them, I had opportunities to explore work outside of architecture. It was then that I learned how other fields, particularly gaming and IT, would engage with the public. This experience proved invaluable when I returned to Korea and later joined Cheil Worldwide when they were establishing the Brand Experience Group.

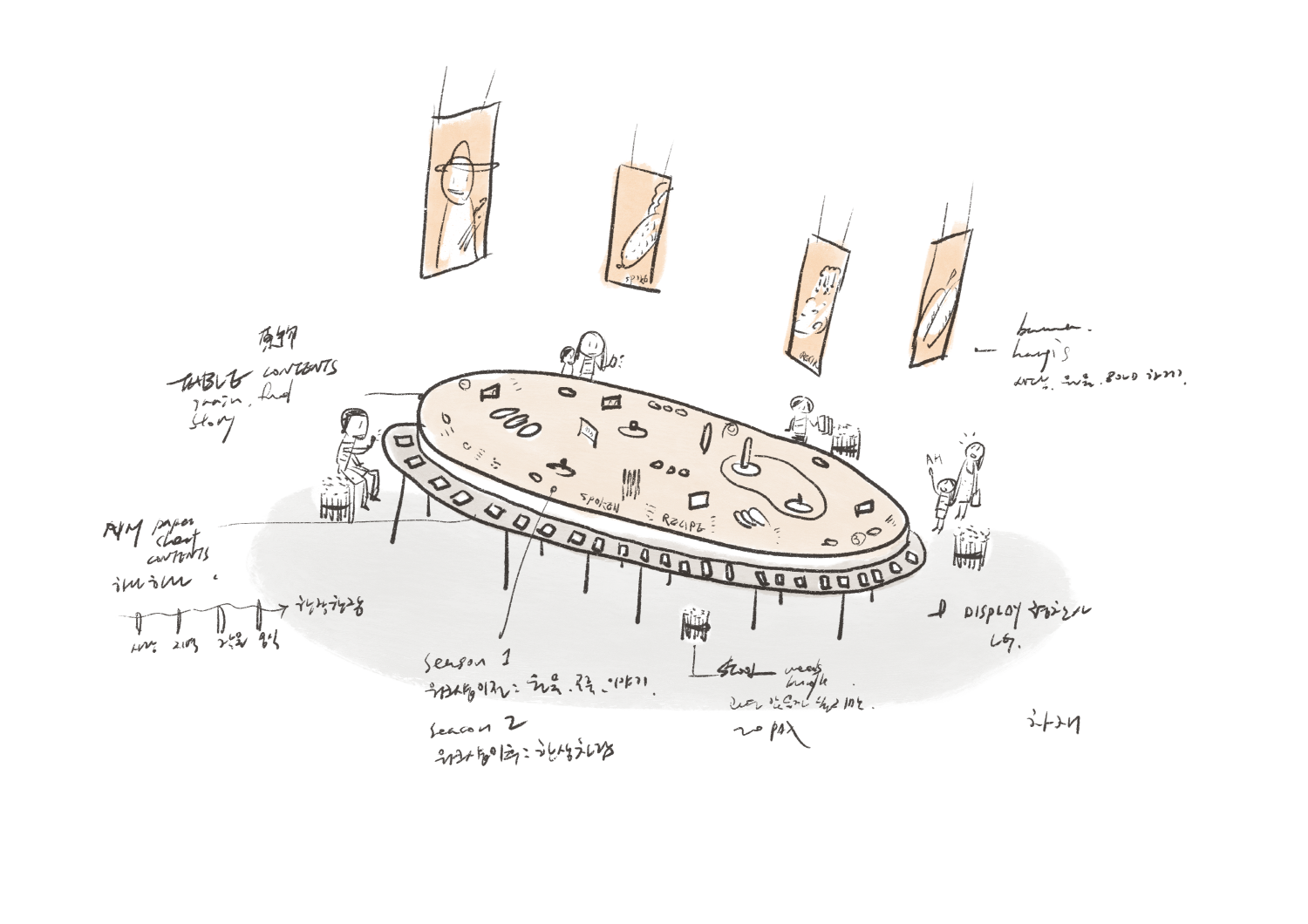

Cha Jae’s drawing imagining the scene of the exhibition, when he was the space director for the exhibition ‘The Recipes from the Earth’ (2023) at the National Agricultural Museum. ©Cha Jae

Cha Jae’s drawing imagining the scene of the exhibition, when he was the space director for the exhibition ‘The Recipes from the Earth’ (2023) at the National Agricultural Museum. (bottom) Cha Jae (left) and Park Seokhee (right) were directly involved in the construction of the first Veke project. ©Natural Sequence Architects

In Desire of Full Contributions and a Swift Response

Kim: Despite the wide range of projects studio mmer takes on, do you have one fundamental guiding principle?

Cha: I always aim to contribute fully to a project, to the extent that I can confidently say I was a part of it. I always think, ‘What does it take for me to say that I truly did this project?’ That question has guided how I choose projects—I only take on ones where I can confidently say that I was ‘fully involved’ from start to finish. Being engaged in the entire process is something I genuinely enjoy. One of the most memorable moments for me was during the first Veke in Jeju when we were pouring concrete. The construction worker above was coughing as he mixed different materials to get the right black concrete blend, while I was shoveling, mixing, and pouring the blend. There was no vibrator and therefore to settle the concrete, everyone took part in pounding on it. I took part as the creative director starting from the planning of the contents and space, refining things through design, constructing, and resolving problems during the operational phase, all done in collaboration with the project owner and landscape architect Kim Bongchan (principal, The Garden), art director Choi Jeonghwa, and architect Park Seokhee (co-principal, Natural Sequence Architects). Everyone contributed across all aspects of the project. It was truly an enjoyable experience to the point where I feel as if I don’t smile as brightly either ten years before or after that time, and this shows in the faces of everyone.

Kim: You published an album taking part as a member of the ‘band beenu’. That must also have been a really enjoyable experience as well.

Cha: Of course, that was a great time as well. I’m not sure if I smiled as brightly as I did in this photo, though! (laugh) Speaking of the band, it made me realise how much I craved immediate feedback. With large-scale projects backed by massive capital or national significance, the design phase takes several years, and construction takes even longer. As a result, it takes too long to receive any feedback, and even when you do, it’s difficult to apply those insights to the next project in a meaningful way. At Cheil Worldwide, creating spaces as content and designing brand experiences provided instant feedback helped satisfy this craving. Since becoming independent, I still work on urban-scale projects, but I strive to keep things as light and agile as possible.

Kim: How is the reorganisation of studio mmer progressing?

Cha: The things that I can do under the name of the ‘studio’ is quite limited. The word often gives a connotation of something that is experimental, gives an impression of working on small projects, and this sometimes tricks you into self-limiting your limits to these perceptions. To expand our scope, I’m preparing to launch a company called remm Korea, which is essentially ‘mmer’ flipped backward. remm Korea will focus more extensively on regional and spatial development projects from a brand urbanism perspective. Instead of filling cities with developments driven solely by financial calculations, we aim to shape urban spaces with alternative, locally rooted content. For this type of local development to be successful, we need small business owners and small brands to thrive. This is why we are also planning educational programmes that will help strengthen the competence of these local players.

Cha Jae, our interviewee, wants to be shared some stories from Chae Ahram (principal, Studio UDTT) in March 2025 issue.