SPACE April 2025 (No. 689)

Entrance of SHARE-US Evenesel (first branch, 2015)

Based on his experiences building houses as a university volunteer and repairing houses as a novice practitioner, Hyun Seunghun of SUNLABARCHITECTS (hereinafter SUNLAB) founded his firm in 2013. Considering it his mission to tackle areas where society needs architects, he has devoted more than a decade to private-public partnerships that remodel substandard gosiwons (a facility with tiny studio units in a shared house) at minimal cost into shared residencial housing. Behind SUNLAB’s experiments – partitioning a one-pyeong gosiwon into different kinds of units and connecting them across shared spaces to make them livable – reveal their design foundation to be one of meticulous investigation and research. Jo Jaehyuk, a researcher who pounded the pavement to elevate gosiwons and gosichons (gosiwon villages) into a shared public forum for discussion, also joined forces. SPACE met with them to discuss the potential and future of the gosiwon as an alternative form of housing and a hub for urban regeneration.

Hyun Seunghun principal, SUNLABARCHITECTS, Jo Jaehyuk partner, SUNLABARCHITECTS × Bang Yukyung

Exterior view of SHARE-US Sillim (fourth branch, 2019) ©Kim Yongseok

Gosiwons and Gosichons

Bang Yukyung (Bang): First of all, congratulations on winning the Korea Young Architect Award last year. It seems that this recognition has prompted a new perspective on the gosiwon.

Hyun Seunghun (Hyun): Thank you. We really didn’t expect much, since we assumed our work wouldn’t readily be viewed as ‘architectural work’ by those in the field, so we were equally surprised to hear the results. (laugh)

Bang: Looking over your past activities, it seems you haven’t necessarily been spotlighted within architectural circles, but have been introduced by various media outlets, including those in the public sector, as a practical example of a social enterprise capable of providing insight into social issues such as alternative forms of housing.

Hyun: Indeed. Starting from house-repair volunteering efforts on the Gwanak Dongjak Sunrising House, we undertook several intermediate steps before it became linked with a Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) pilot project. As more gosiwon remodeling projects were completed, a few media channels took an interest and featured them occasionally. Personally, winning the Korea Young Architect Award became an important opportunity to look back over that entire body of work and evolution of our design as an architect. I’m grateful to everyone who resonated with our work and our aims.

Bang: Could you briefly explain the process that brought SUNLAB to its current point?

Hyun: I’m originally from Jeju Island. After coming to Seoul for college, I moved around and lived in multiple temporary accommodation facilities – gosiwons, boarding houses, rooming houses, studios – like a nomad. I studied how to craft a ‘concept’ in architecture school, but it felt incompatible with my lived experience in that I couldn’t freely choose or change where I lived, despite learning an architecture focused on ‘myself’. Then, during my undergraduate degree, I volunteered in Cheoram and Inje building houses, which turned my attention to an ‘architecture that society needs’. Even after joining an architectural firm, I took part in house-repair volunteering on weekends and searched for a link between my architectural work and volunteer service. Around 2012, by chance I saw a poster for SMG’s Social Economy Idea Contest. Together with my friend Sung Cheolhwi, who volunteered and worked at the same firm, we proposed a project to improve housing environments by systematising repairs and remodels in areas difficult for architectural experts to access. We were happy to be selected, but it turned out to be the preliminary stage of a startup programme: we had to launch a business through the programme in order to receive tangible support, education, and consultation. After about a month of deliberation, my friend and I quit our jobs and established SUNLAB—adding

the concept of the ‘lab’ to the ‘Sunrising House’ repair activities we had been working on.

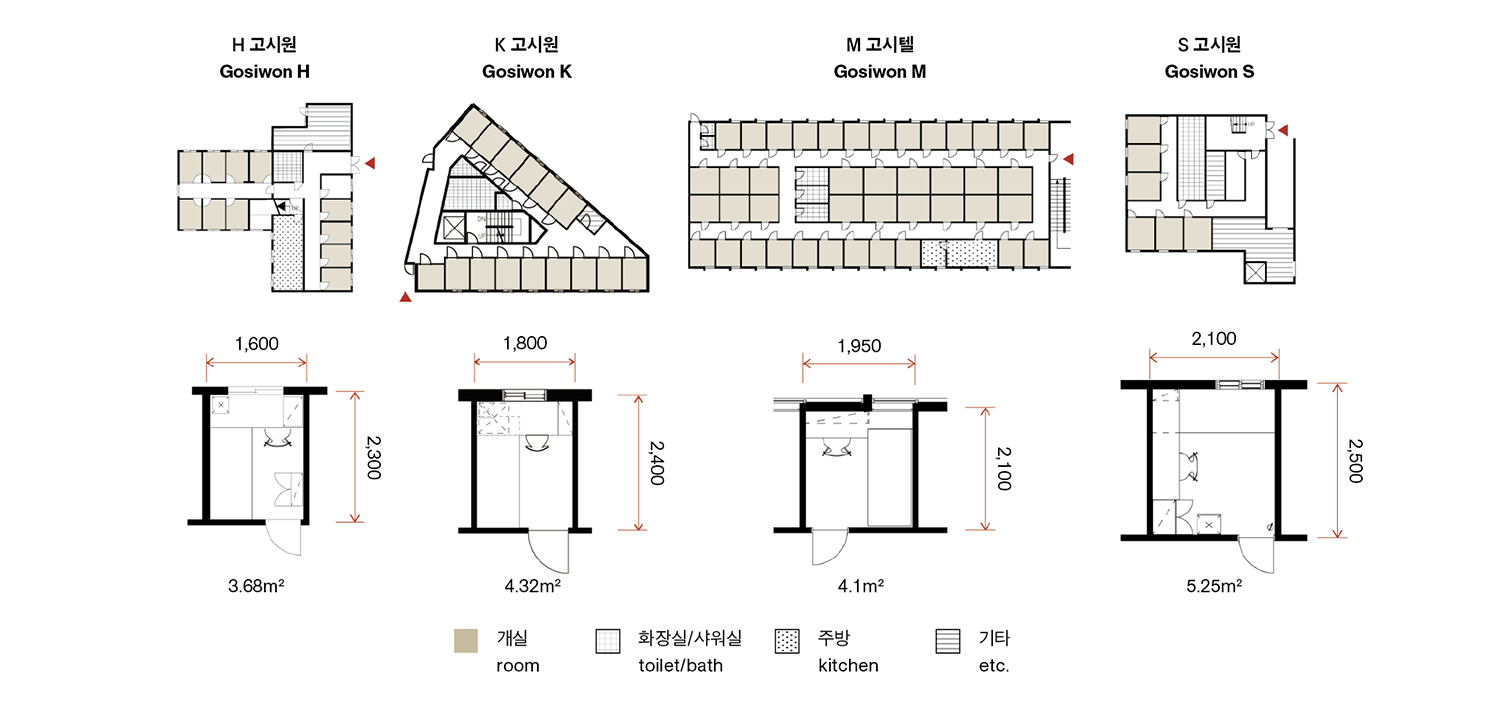

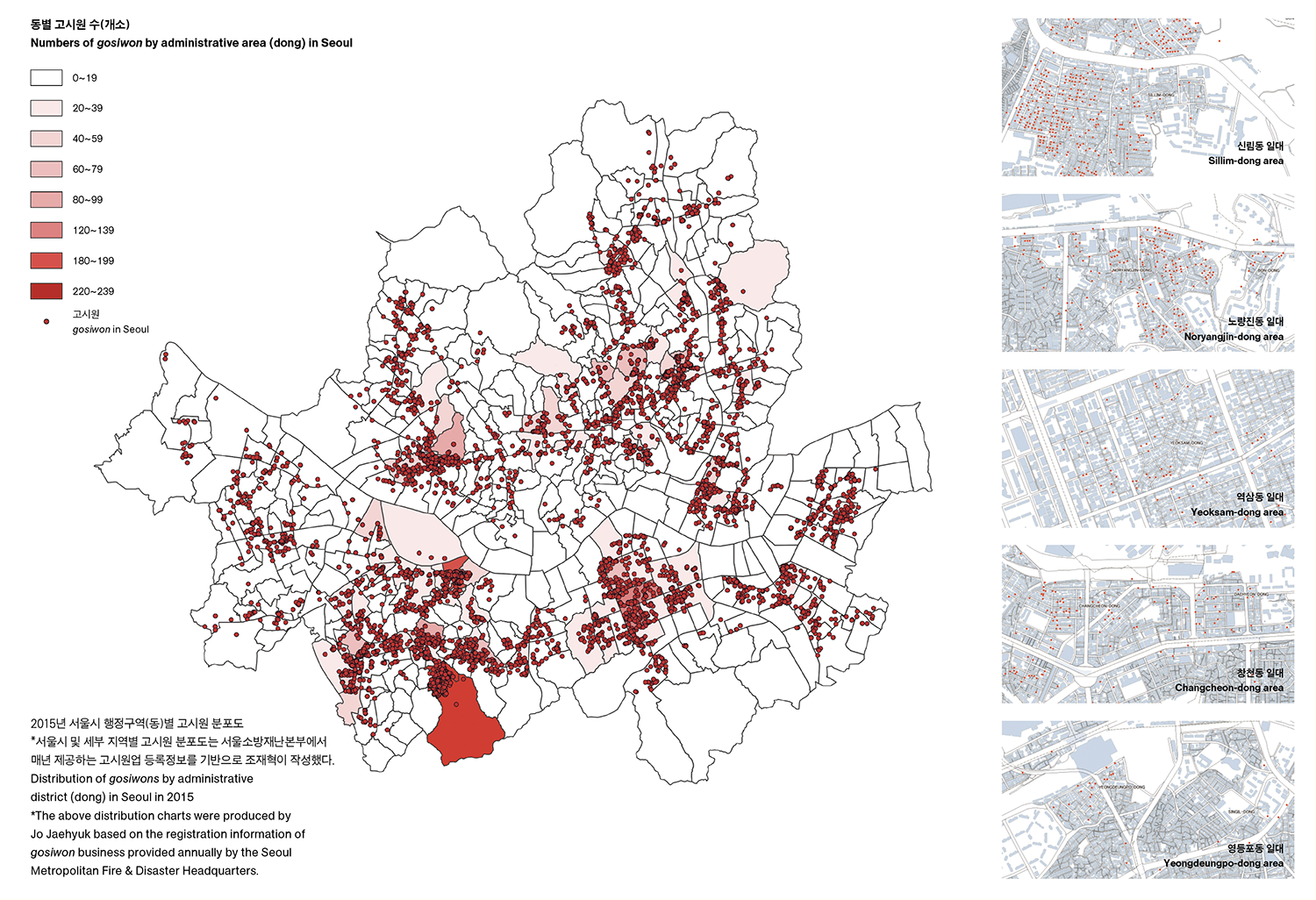

Floor plans of gosiwons (top) and layouts of each room type (bottom), drawn by Jo Jaehyuk

Bang: Jo Jaehyuk is in charge of research. How did you come to join SUNLAB?

Jo Jaehyuk (Jo): I majored in architecture as an undergraduate and then worked in the field. Later, I went to Japan to study, and my research focus became gosiwons and gosichons. I heard that someone in Korea was working on that topic, so I visited Hyun Seunghun out of the blue. After getting acquainted, we kept in touch. While working on my master’s and doctorate, I participated in field surveys closely examining gosiwons across Seoul—in Sillim-dong, Yeongdeungpo, Sinchon, Jongno, Dongdaemun, and Gangnam, and so on.

Hyun: SUNLAB was formed by architects and designers, but once we were asked in the pilot project to create physical spaces grounded in investigations of gosiwons, we joined forces not only in research but also spatial design. The layout of units and shared spaces emerged from that collaboration with Jo. After SUNLAB amassed several remodeling examples, in 2017, we took part as architectural researchers in an SMG-commissioned gosiwon actual condition survey project, together with the Korea Center for City and Environment Research. Jo was also on that project, and after finishing his doctoral dissertation and returning to Korea, I asked him to formally join us, so he’s been here for the past three years.

Bang: Why did study Seoul’s gosiwons from Japan, not in Korea? I’m curious about your primry research focus.

Jo: I wanted to explore a different possibility after I’d worked a bit in the field, so I went abroad for further studies. Back then, I paid more attention to gosichons than individual gosiwons.

I thought that by objectively examining the distinctive traits that emerge when gosiwons cluster densely, I speculated that we could potentially uncover possibilities in the domain bridging city and architecture. For example, when are gosiwons concentrated, the nearby cram schools, laundromats, convenience stores, cafés, and local restaurants make that entire neighbourhood appear like a home. You sleep in a gosiwon, study together in a reading room, go to a café to meet friends, and eat in a local diner—all within the gosichon. I started researching whether this phenomenon – where the various functions of a home are distributed across a neighbourhood – might be converted into an urban housing concept. But because of Korea’s preconceptions, people would ask, ‘Even if you study it, who’s going to care?’ Meanwhile, researchers in Japan found it intriguing and saw enough potential to offer collaboration and research grants. So, I carried out a fully-fledged research project there, mainly tracing where gosiwons and gosichons originated, how gosiwons came to be concentrated in specific areas, and how they are used collectively. By analysing gosiwon residents’ lifestyles and living patterns, I noted how the issues facing each neighbourhood can differ, requiring distinct solutions.

Hyun: When we meet other architecture or urban scholars, they often say ‘We ought to eliminate gosiwons.’ We see it differently. Jo insists gosiwons must remain, while I believe they must change. Jo interviewed many residents as part of his fieldwork, which is challenging because they have to talk about personal hardship. I was impressed at how he derived patterns from that data.

Jo: I had to initiate these interviews by dining together. We’d eat at a local gosichon eatery and listen to their everyday chit-chat. If I just show up, they’ll never open the door; I have to visit multiple times until they finally open up.

Bang: Did anything in the interviews stand out? Was it helpful in terms of identifying the desires of gosiwon residents for remodeling?

Jo: I realised how important communal facilities are. Typically, gosiwons are closed off because they lack shared spaces, or if they do have them, they’re limited solely to residents and not open to outsiders. But, through research, I found that wherever gosiwons are concentrated, certain facilities naturally emerge to connect with the local community. For instance, in Noryangjin’s gosichon, a church at the centre of the neighbourhood offers free breakfast at dawn, and students flock there. Later, those who pass their exams send rice or donate money to keep it going. That’s a virtuous cycle. In contrast, in Yeongdeungpo’s gosichon, which has many day labourers, people gather at an off-track betting spot at 2 p.m. to gamble away their pay, then disperse to their gosiwons. Seeing how such hubs form made me realise we can use them to transform the gosichon area. This was confirmed at Shillim Darak, the shared lounge in the fourth branch, SHARE-US Sillim (2019), which was initially a residents-only community space. We converted it into a café for sustainable operation, opening it up to local residents and making the area livelier. We hope to feed these insights into gosiwon remodeling prototypes.

Hyun: When we first tackled gosiwons, we tried to address issues like isolation and anonymity through ‘sharing’. Meanwhile, Jo interpreted them in terms of the relationships they encourage within the neighbourhood. The two approaches complement one another and create synergy.

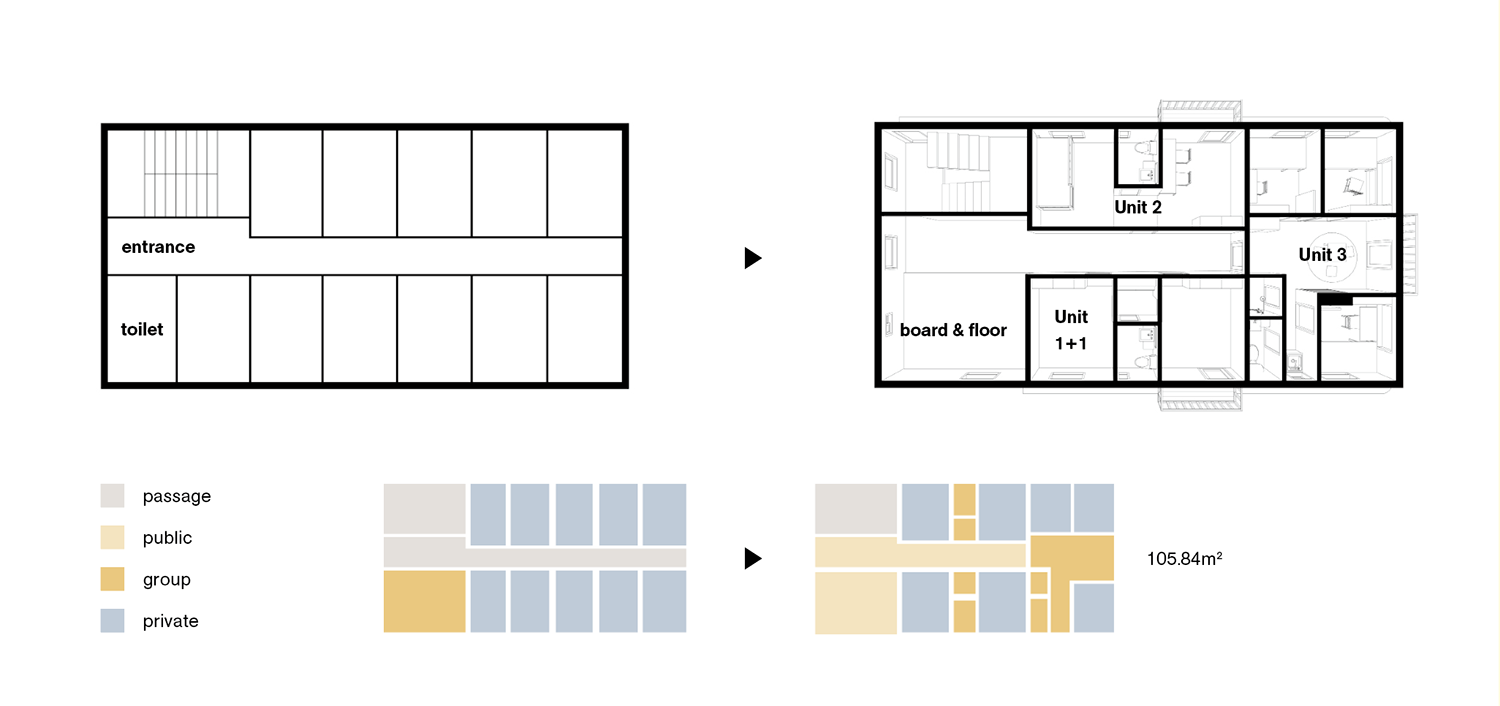

SUNLABARCHITECTS transformed Evenesel Gosiwon into a SHARE-US Evenesel, dividing the floor plan through common areas. The Unit 1+1 consist of two private rooms for two individuals, sharing only the entrance and bathroom. Unit 2 is a dormitory-style space for two individuals, and Unit 3 accomodates three individuals with private rooms that shares living room. The original gosiwon with layout of 11 rooms was remodeled to a shared residential space for 7 individuals.

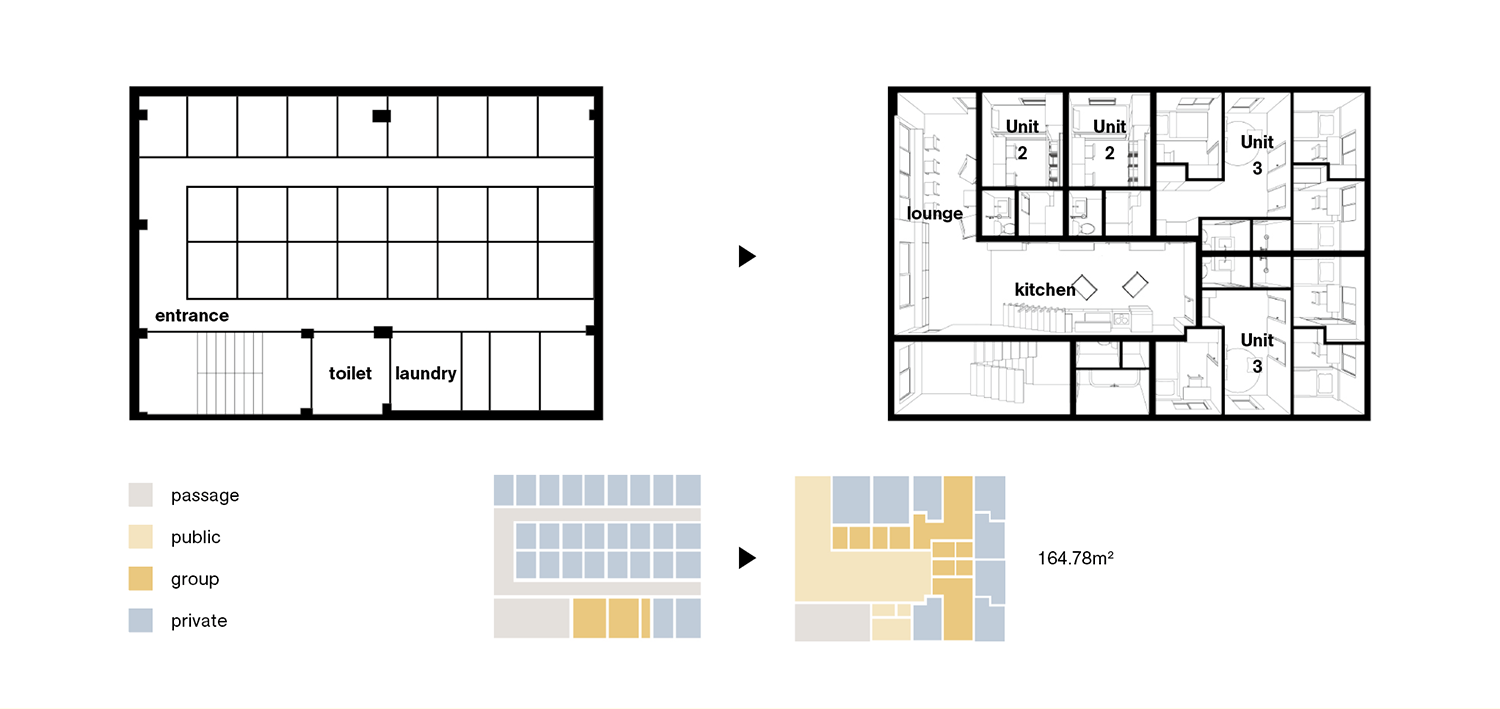

SUNLABARCHITECTS transformed Geosung Gosiwon into a SHARE-US Geosung (third branch, 2017), converting the circulation area into a shared space. The original gosiwon with layout of 27 rooms was remodeled to a shared residential space for 10 individuals using a combination of Unit 2 and Unit 3.

From Research to Implementation: The SHARE-US Experiment

Bang: SHARE-US is the name of the gosiwon remodeling project SUNLAB conducted with SMG. You’ve already completed five branches—can you describe your process?

Hyun: After our proposal was chosen at the 2013 Idea Contest, we refined it in 2014 under SMG’s Innovative Social Enterprise Public Offering Project, to become the ‘Alternative Model Project for Gosiwons’. We spent six months on research, receiving some public funding for remodeling, and leased a gosiwon for five years as a pilot. Because it was a public project, the goal wasn’t profit, but rather to propose a remodeling prototype and an operational model. That gave rise to the first branch, SHARE-US Evenesel (2015), which ran on a six-month cycle (moving in every March and out in August, then in again September and out in February) to align with local university terms and exam schedules in the gosichon. But because we set the rent fairly low, in line with local market rates, without factoring in the firm’s actual operational costs, we struggled to secure adequate funds for maintenance. Although the vacancies were near zero, we hadn’t accounted for follow-up costs, and as a design-centric firm, we realised we needed to adjust our team structure and business model. Building on that experience, we collaborated with SMG’s Housing Policy Division to institutionalise our work under the name ‘Remodeling Social Housing Pilot Project’. SMG redirected part of its youth dormitory budget toward this effort, leading us to open SHARE-US Geosung (second branch, 2017) and SHARE-US Cheonggwang (third branch, 2017) in succession. Around then, the gosiwon project fell fully under the ‘social housing’ concept, in step with SMG’s policy direction.

Bang: While the first to third branches were leased for a certain period and partly funded by the public sector for remodeling, the fourth branch merged with a Living Culture Support Center, where SMG purchased the land and building directly, then subsidised part of the rent. Why did the public support model change?

Hyun: That was because it was difficult to find a suitable private property for long-term leasing. So, SMG switched to acquiring spaces and then renting them out. We classify them as within a ‘lease model’, where the public funds construction, and an ‘acquisition model’, where the rent is lowered. With the lease model, we could select sites based on our full survey of Sillim-dong’s gosichon. That process was possible thanks to prior investigation.

Bang: How are the records and data generated during your research and operational processes actually being used?

Hyun: In conceptual terms, we put together our initial materials based on research Jo’s work. At the same time, the accumulated operational records have gone toward facility maintenance, which is key to a project’s sustainability. We aim to reduce costs by comprehensively considering the number of managers, what must be managed, and how much time is required. Concentrating move-ins and move-outs within a day or two – checking residents in and out and confirming payments – is also a way to protect our designers’ working hours. Interestingly, the know-how we acquired by constantly seeking greater efficiency ended up translating into cost savings. We encountered two major shifts. First, in terms of communication with users, we moved on from posting flyers and fielding phone calls to sharing an FAQ on social media, creating a more systematic manual in the process. Second, there’s the management of utilities such as water, electricity, and gas. Previously, dividing the bills equally (1/N) caused them to skyrocket. Starting with our second branch, we introduced individual metering and sent out separate statements. Having gathered nearly ten years of data this way, we discovered differences in energy usage and lifestyle patterns depending on unit type or area. We also created diverse graphs by factoring in individual preferences and variations—something that caught the interest of researchers at public institutions.

©SUNLABARCHITECTS

The shared spaces for residents of SHARE-US Evenesel (top) and SHARE-US Geosung (bottom) ©Kim Yongseok

Bang: It sounds like that information could become the basis for future policies or projects.

Hyun: We approach this conceptually as shared housing, but institutions – especially those in the public sector – are highly focused on the category of ‘non-housing’. Gosiwons are technically neighbourhood living facilities (hereinafter geunsaeng), yet they are in practice used as housing. The main question is how to develop these geunsaeng properties. Housing policy typically relies on developing land on the urban outskirts to supply rental units, but we’re proposing a model that uses existing geunsaeng buildings in central urban areas. Gosiwons are one example; more recently, the Korea Land & Housing Corporation has been remodeling hotels. In reclaiming underused spaces like this, some projects link up with broader urban regeneration efforts. As a result, we end up taking on a wide range of roles, from architect to landlord—research, planning, development, construction, and operation all rolled into one.

Bang: It seems you’ve discovered a pioneering new way for architects to join public sector projects. I imagine there must have been many invisible challenges in mediating between the private and public domains, building the project structure, and institutionalising it.

Hyun: Since we had no capital for land, construction, or ongoing operations, working with the public sector was one of the few ways of trying anything new. We’ve basically become experts at connecting our projects to public funding. (laugh) Through these activities, we’ve become familiar with words rarely used in architecture—like attracting investors or IR (investor relations). It’s know-how we picked up by experiencing how business structures and the flow of capital work in real life. People who don’t understand the risks even have trouble drawing up business plans, but thanks to our wealth of experience, we’ve reached a point where we can sense cost feasibility almost intuitively.

Bang: I also heard, Jo, that you lived in a SHARE-US branch—what was it like from a user’s perspective?

Jo: I experienced the difference between a manager’s standpoint and a resident’s standpoint. One big issue was how to handle relationships or complaints among tenants. It’s such a diverse group of people that they all report their inconveniences to the manager, who can end up doing emotional labour. Mediation is required between those who like to gather and carry out group activities in shared spaces and those who don’t, so I realised we need very detailed guidelines for operations.

Hyun: Internally, we even introduced the French gardien system, under the name of ‘supporters’, so someone could act as the liaison for the resident community. We compensated them by deducting a portion of their utility fees.

Bang: You obtained official certification as a social enterprise. I assume SUNLAB has an operating philosophy of its own.

Hyun: We sought that certification deliberately after founding the firm, because architecture has a strong public dimension and we wanted to demonstrate that our office is premised on a social mission. I feel gratified when I see designers, managers, and others who have passed through SUNLAB taking what they learned here into other projects or startups – those experiences have, I believe, had a positive impact.

©Kim Yongseok

Lounge on the third floor (top) and Unit 5 (bottom), SHARE-US Geosung (remodeled third and fourth floors) ©Kim Yongseok

Greater Diversity in Urban Housing

Bang: You spent eight years in Japan working on your dissertation. Were there any cases that influenced your perspective?

Jo: I arrived in Japan in 2013, right after the Great East Japan Earthquake. At that time, Japanese society was abuzz with the idea of sharing living spaces and spreading risk together. This gave rise to many new shared houses and corresponding research. One memorable example was Apartments with a Small Restaurant (2015) in Tokyo’s Meguro area, designed by Naka Architects’ Studio. The property owner had once lived in a shared house, but, after getting a partner, expanded that communal-living model to accommodate two-person households. The first floor had a small community restaurant, while the second and third floors were configured for pairs. They really thought about ‘what to share’, designing contact points: for instance, they placed a common laundry area in the corridor rather than inside the individual units, and arranged the entrance so residents would pass by each other’s living rooms. Another interesting example was the Yokohama Apartment (2009) by ON design partners, which experimented with different forms of shared housing. Four units have been placed back-to-back, and each occupant must pass through a shared living room on the ground floor. Still, I felt it was contradictory that while these were innovative works, they largely remained single ‘architectural pieces’ that didn’t fully expand into challenging structural issues in wider society.

Hyun: Broadening the diversity of urban housing is crucial. Gosi-yeonguwon, the precursor to modern-day gosiwons, first appeared in the 1950s. From the 1970s to the 1990s, it served as a place for exam preparation and lodging, and in the 2000s, it evolved into short-term urban housing for low-income single households. This history demonstrates how flexible it is. Meanwhile, the proportion of older men living alone in gosiwons is also noteworthy. In other words, at some point in their life cycle, many people experience gosiwons. Because it’s a temporary dwelling for socially disadvantaged individuals who can’t easily voice concerns about housing, I see it as precisely where architects must intervene for qualitative improvement.

Jo: In a gosichon, the ‘incomplete’ aspects of living in a gosiwon are supplemented by exam prep schools, ‘gosi-buffet’ eateries, and reading rooms that form a quasi-community, sometimes offering discounted packages. We could apply a similar approach to other neighbourhoods, appointing a local coordinator who curates or connects multiple facilities by theme – without necessarily building big complexes – linking people through their preferences and activities. That could lead to urban regeneration and community revitalisation.

Bang: You introduced the term ‘shared residential housing’ to redefine gosiwons. Sometimes ‘shared housing’ and ‘social housing’ are used interchangeably—how do you differentiate between them?

Hyun: ‘Social housing’ isn’t a legal term, but an SMG ordinance providing public housing to those below a certain income level. I personally avoid calling it ‘social’, since it can overshadow other qualities—like, ‘It’s fine if the space is cheap and not as complete.’ Another reason is that we hoped our work might be recognised under a separate institutional term, distinct from generic shared houses or shared housing. In reality, a shared house indicates an operational structure or system, while ‘shared housing’ refers more to the spatial concept. So we borrowed ‘urban residential housing’ from the Housing Acts, calling our projects ‘shared residential housing’ starting with the second branch, SHARE-US Geosung.

Jo: Under the Housing Acts, gosiwons are ‘quasi-housing’, along with senior welfare facilities and officetels—another term unique to Korea. It’s important to explore and experiment with such gray areas of alternative housing to diversify urban dwellings overall and expand the public conversation. Doing this kind of research can be lonely, but I believe the priority is for experts in academia and architecture to refine the critical language and form a new consensus.

Bang: Laws, administration, and policy clearly lag behind these rapid shifts in our conceptualisation of housing. As one of the leading researchers and practitioners in gosiwons, what do you focus on now?

Jo: In 2015, there were 5,921 registered gosiwons in Seoul, according to official statistics. Considering the average of 30 – 40 rooms per gosiwon and a vacancy rate of 20 – 30%, there were around 200,000 total rooms, with 140,000 – 160,000 (about 150,000 people) actually residing in them. That was roughly 13.4% of the city’s single-person households at the time (1,115,744). After peaking in 2015, the number of gosiwons steadily declined, dropping to 5,074 by 2024. Some predict that gosiwons will eventually disappear, but even if they physically vanish, the lifestyles or patterns established in gosichons may persist in another form. As such, I’m interested in how gosiwons transform or evolve. We’re considering ways to synthesise SUNLAB’s extensive archives and activities into a new research outcome.

Hyun: I think the key lies less in gosiwons themselves than in the alternative housing programmes that can stand in for conventional homes. That’s exactly where society needs architects. Also, I’d like to see the word ‘rental’ in ‘rental housing’ replaced with a different term. ‘Rental’ suggests a purely transactional idea – paying money to borrow something – whereas we want a term that captures the value of living space from the user’s perspective. I believe trying to formulate a new language can be a meaningful step toward improving how society perceives housing.

Exterior view of Shillim Darak at SHARE-US Sillim

The interior of Sillim Darak, a shared space created by connecting the first and basement floors of SHARE-US Sillim, currently used as a café.