SPACE April 2025 (No. 689)

The Dokebi Platform amidst the dense urban fabric of Banghak-dong, Dobong-gu. In contrast to the crowded surroundings, it presents a calm, white appearance.

Merchants busy carrying their loads, an elderly woman picking out fresh spring vegetables, thick smoke rising from a large pot, and a bicycle zigzagging between them all—the Dokebi Platform is located in the bustling crowds of Dokkaebi Market at Banghak-dong. A white box sits quietly on top of an existing public parking facility, set within this noisy backdrop, offering something like the shade of a tree on the side of the road and attracting the gaze of those coming and going below. Plot Architects (co-principals, Kim Myoungjae, Choi Yeojin) share their insights and thoughts on the transformative potential of public facilities, as spaces that exist everywhere and are open to everyone.

interview Kim Myoungjae, Choi Yeojin co-principals, Plot Architects × Youn Yaelim

The Dokebi Platform, renovated from the public parking facility of the Dokkaebi Market

Youn Yaelim (Youn): The Dokebi Platform project was initiated in response to the 2022 ‘Seoul Breathe Space Competition for Leisure Spaces’, hosted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG). It was an open call for ideas, where any publicly accessible space in Seoul, such as streets, parking lots, parks, riversides, and the interior or exterior of public buildings, could serve as a potential site for new construction. In this sense, selecting the site itself was a significant part of the project. What led you to discover Banghak-dong in Dobong-gu as your project location?

Kim Myoungjae, Choi Yeojin (Kim, Choi): The competition was part of a SMG’s initiative to create a space for its citizens, aiming to discover accessible public areas and to propose suitable designs for these spaces. We chose Banghak-dong as our site because of our previous experience working in Dobong-gu as ‘village architects’ on a similar project. Although it doesn’t exist anymore, SMG once assigned village architects to each district to advise on and plan local spatial policies, with the goal of improving small-scale public facilities closely tied and attuned the daily lives of residents. One of the tasks of these village architects was to discover spaces that needed improvement and to seek new values within them. The idea for the Dokebi Platform took shape during that time. While surveying various parts of Dobong-gu,

we recognised the potential of the public parking facility at the Dokkaebi Market. We only dreamed of realising it someday, and we were met with a pertinent competition which allowed us to come this far.

Youn: The Dokebi Platform is the renovation of a public parking facility at the entrance to the Dokkaebi Market. At what point did you understand the potential of this space to become a place of rest and repose for the community?

Kim, Choi: The Dokkaebi Market is a beloved traditional market among local residents, always bustling with life and full of a vibrant energy. The same goes for the small park that faces the north side of the public parking facility. We still remember the first time we visited this place. It was a hot summer day carrying a heat warning, and it was hard to even walk a few steps. We kept walking around the neighbourhood in search of a target and saw old men and women squatting on a crumbling bench in front of the parking facility and on the steps. After making a full loop around the neighbourhood, we returned to find the same spectacle, and on another evening, the same scenes again repeated themselves. Many people also used the nearby park for walks or exercise. On such an unbearably hot day, you wouldn’t normally expect to see people outside, but this place naturally drew people in due to its location at the market entrance, its connection to the park, and its function as a parking facility. Moreover, aerial photographs revealed the neighbourhood densely packed with houses, leaving virtually no open space except for this one. We wanted to make the most of the existing facilities and the park to create a high-quality outdoor space, which would be open and welcoming to everyone. During our subsequent survey, we discovered that Banghak-dong has the highest proportion of elderly residents and recipients of National Basic Livelihood Security Program in Seoul. It seems that in areas where people face economic hardship, the use of public outdoor spaces and the strength of community ties tend to be greater. This gave us confidence that the model we proposed would work especially well here. If this had been in Gangnam-gu, we likely would not have designed it in the same way.

Aerial view of the Dokebi Platform. The grid system applied to the extension acts as a guide, helping the space to be perceived as a unified whole.

The bench on the ground floor of the Dokebi Platform. A corner offering anyone a quiet spot to rest for a moment. Red bricks were used to harmonise with the building’s original façade.

Youn: What condition was the public parking facility and its surrounding area in prior to the renovation?

Kim, Choi: The public parking facility of Dokkaebi Market was originally composed of a two-storey underground parking garage and a single-storey administration building next to it, but, over time, it was added to several times due to the needs of the residents. On the ground floor, a community café is located, and container units were added on top of the parking structure to host local self-governance activities, leading to incremental expansion. In the beginning, the space was actively used across a range of programmes, but what with the prolonged suspension of activities during the pandemic, maintenance became difficult and the facility deteriorated. Moreover, the programmes that were run voluntarily by residents, while well-intentioned, had the disadvantage of being perceived as closed spaces as certain groups took over the space. The north park was being used in complete isolation from the back of the neglected building. We decided to remove the haphazardly constructed containers and design a shelter that would accommodate the existing programmes, but would be flexible and open to a wider audience.

Youn: A small rest area with brick benches was created at the front of the building, while a tiered seating area was built at the back, exploiting the slope of the parking structure. This stepped seating naturally connects to the courtyard on the second floor of the building, which links directly to the adjacent park. How did you envision the separate roles of these outdoor spaces?

Kim, Choi: We consider the degrees of interaction when designing various types of open spaces and shelters. First, the bench on the ground floor is a small gesture, but it served as a key starting point from which the entire project emanated. By using the same red brick as in the building’s original façade, we aimed to create a corner that would be in harmony with the existing environment and offer anyone a quiet spot to rest alone for a moment. Second, on the north side of the building, we adjusted the roof slope at the top of the parking ramp to create a stepped shelter. Here, we envisioned people sitting, resting, and chatting, which we hoped would expand on the activities that already take place in the park. At the top of these steps lies the courtyard, designed as a space not just for brief rest, but for lingering and interacting with others. As the name suggests, Dokebi Platform is a project focused on outdoor space. We began the design by first envisioning and drawing the courtyard that would feature at the heart of the site. Since our aim from the start was to create an outdoor space, there was no reason to cover it with a roof. The various box-shaped structures arranged around the courtyard were conceived with the assumption that their doors would always be open—not as enclosed rooms, but as temporary shelters supporting outdoor activities. The structure allows for flexible use, being separate yet becoming one when the doors are open.

©Plot Architects

The façade of the original public parking facility (top) and the renovated façade (bottom)

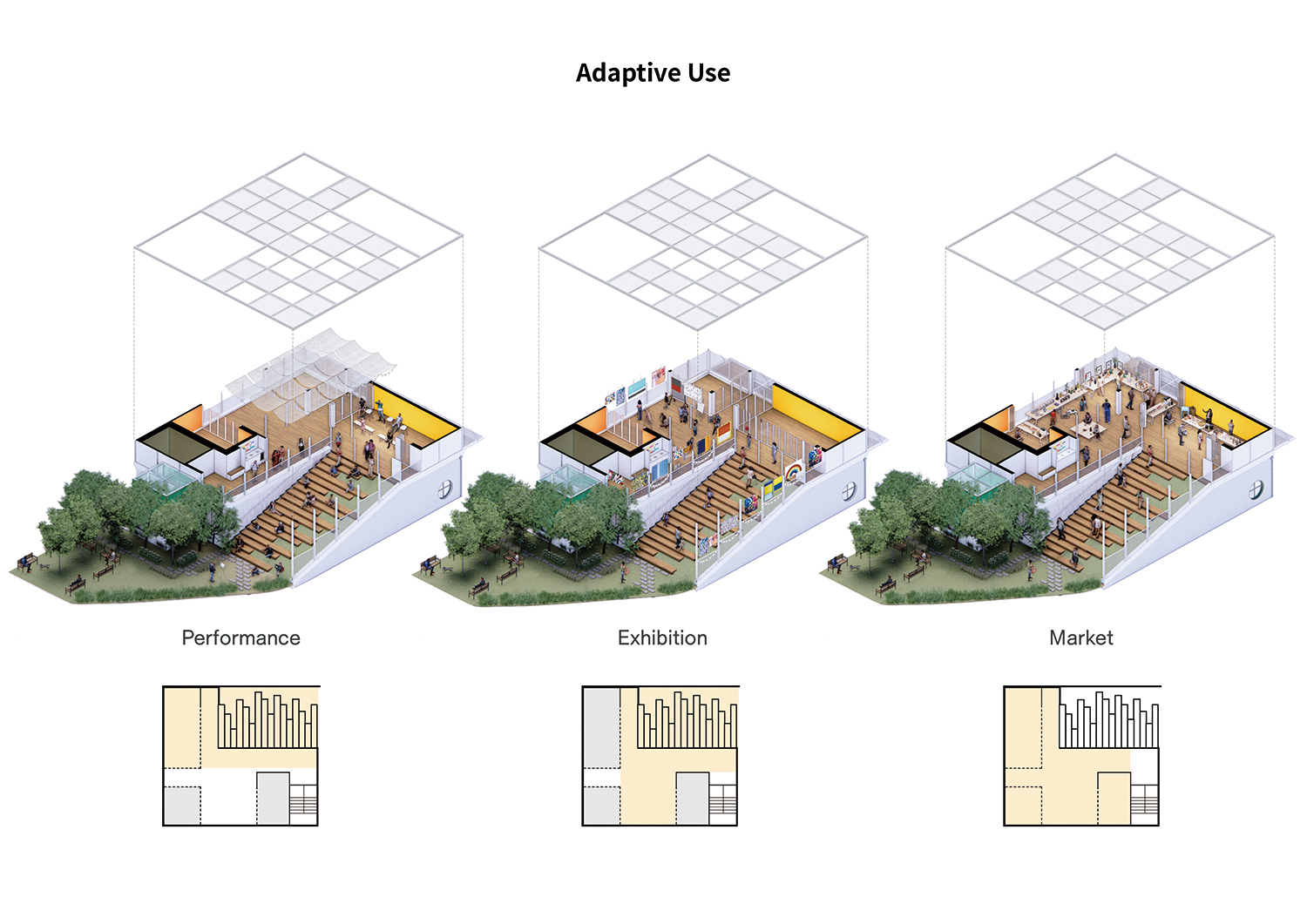

Diagram imagining the diverse possibilities of the Dokebi Platform’s use. It was designed to be adaptable to the changing needs of residents. The grid system allows for the organic use of the space.

Youn: Although the space is divided into three separate boxes and a courtyard, from the outside it reads as a single, unified volume. The previously isolated container modules were integrated into one clean, white, and flat structure. The grid system applied to the extension likely played a key role in achieving this sense of cohesion.

Kim, Choi: If you look around, you can notice that the urban fabric is very small. There are hardly any apartment buildings. Instead, the neighbourhood is filled with tightly packed low-rise houses, and the streets are densely packed with everything from signs to markets. We wanted the Dokebi Platform to have a strong presence as a community facility, so we decided to make it completely different. To do this, it needed to be whiter and calmer so as to stand in contrast to its crowded surroundings. Therefore, rather than dividing the building, we used a single box that encompasses the parking facility entrance and administration office and hoped that this would create a degree of visual recognition. The grid acts as a guide to read the space as one. Depending on which parts are filled or left empty, the use of the space changes, but the overall appearance remains unaffected. The challenge was that the roofs of the parking facility and the administration office had different conditions. To make them appear as one, we meticulously investigated the existing conditions and drew several detailed plans; quite a challenging task.

The grid system was also introduced to enable a more organic use of the space. Just as the original facility had evolved over time, we wanted to create a space that would be able to adapt to our changing times and the evolving needs of residents. We wanted to create a space filled with as much potential as possible. At one point, we even considered creating a structure that could physically move. Of course, that wasn’t feasible given the limited budget and conditions of a small public project. (laugh) Still, the grid holds just as much potential. As we designed the space, we imagined different possibilities of how it could be used for performances, exhibitions, or markets, and developed the design by envisioning these scenarios. Though some of these ideas haven’t yet been realised, we believe they’re fully possible in the future.

Youn: What did you take into account when selecting the materials and structural system?

Kim, Choi: The structure is a steel frame extension on top of a reinforced concrete building, and the basic construction method is not unlike a conventional container box. Since it was built in a narrow and busy alleyway, the project was designed to be 100% dry construction from the beginning. With a construction budget of less than 500 million KRW, we anticipated that a small contractor might take on the project, so we selected materials and designed the structure in a way that would minimise on-site errors and allow for easy adjustments, ensuring that any issues could be addressed during construction. We were looking for a material for the roof that could express the grid concept while providing shade, remaining lightweight, transparent, and not entirely solid. We eventually chose grid-patterend FRP panels, which have perforations that cast shifting shadows onto the calm metal-paneled walls and floor, changing with the time of day and the seasons. In the summer, the shadow patterns become especially vivid. We even convinced the client by saying they looked like the shadows of tree leaves. (laugh)

Second-floor views of the Dokebi Platform. Various boxes of different sizes are arranged around the courtyard. The structure is separate, yet becoming one when the doors are open.

Youn: How do you feel after observing how the space has actually been used since completion?

Kim, Choi: The most well-used aspect are the benches on the ground floor. In the afternoon, there are a lot of elderly people shopping for groceries and hikers sitting there. Many people think that the people in the completion photos were staged, but it’s not. We asked the residents who happened to be there that day for their permission to take the photos. (laugh)

In fact, many of the community-run initiatives that had taken place in the previous container boxes were already quite good. In the early stages of design, we reflected a lot on those existing programmes. For example, a shared kitchen was proposed after we heard about a volunteer programme where participants would shop at the market with elderly residents and cook meals together. After the management of the space was transferred to Dobong-gu Office, many of those programmes were removed, but we think the space can be used in a myriad of ways because we left the possibilities open without stipulating what the space should be used for and how it should be used.

These days, residents often gather at lunchtime, bringing their own tumblers filled with instant coffee to enjoy a break together. In the evenings, volunteer patrol members stop by to rest, and regularly, the space is used for dementia counseling run by the public health centre or as a meeting place for the Dobong-gu community office. It’s being used in various ways, but we still hope it will be used more actively. For instance, with the market right in front offering fresh ingredients, wouldn’t it be great to hold a kimchi-making event? Maybe even dry chili and garlic in one corner. (laugh) Of course, things like this require boldness and creativity from those managing the space. One major regret is that we couldn’t replace the elevator due to budget constraints. For elderly residents in the 80s and 90s, reaching this space isn’t easy.

Youn: This project was conceived and realised by both of you, drawing on your imaginative powers. In idea-based competitions like this, how do architects and the SMG work together to develop concrete plans and bring them to life?

Kim, Choi: As architects, we might never get to work on a project like this again! (laugh) Usually, there are guidelines to follow regarding the area, the programmes, and so on, but this project was carried out from the site selection stage based entirely on the architects’ proposals, without such constraints. As a result, the architects’ design intentions were able to be actively reflected throughout the project. The maximum allowable building area was over 200m2, yet the interior space of Dokebi Platform is only about 80m2. That’s how much we prioritised our design intention. The Future Space Planning Office of the SMG, who collaborated with us, fully understood our vision and embraced it with an open mind. At the same time, we believe that the public policy direction at the moment played an important role. There was a general movement supporting small-scale public projects, and this competition reflected that. Since Dokebi Platform began as a pilot project, we hope that the ongoing and future follow-up projects will also be actively pursued so that small public spaces like Dokebi Platform naturally become part of people’s daily lives.

The stepped shelter connecting to the park on the north side of the building. It was hoped that the activities already taking place in the park would expand into this space.