SPACE November 2024 (No. 684)

Project Songhyeon-dong site

Location Songhyeon-dong 48-9, Seoul, Korea

Site area 37,117m2

Site opening 2022 – 2024

‘Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) International Design Competition’ year 2024

Competition site area 9,787m2

Competition building area 25,696m2

Competition organizer Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism

1910 Used as a residence for Joseon Industrial Bank staff

Post-liberation Used as accommodation for the U.S. Embassy

1997 Decision to relocate the U.S. Embassy residence

2000 Samsung Life Insurance purchased the site from the Ministry of National Defense for 140 billion KRW, marking its first privatisation. Development was delayed for 8 years due to regulations

2008 Korean Air purchases the site from Samsung Life Insurance for 290 billion KRW

Mar. 2010 – June 2012 Jongno-gu Office rejectes Korean Air’s request for approval to develop a seven-star Hanok hotel, citing the School Health Act

Aug. 2015 – Jan. 2017 Korean Air proposes a cultural convergence complex (K-Experience), later voluntarily withdraws the plan

Feb. 2019 Korean Air announces the sale of the Songhyeon-dong site

Mar. 31, 2021 Anti-Corruption & Civil Rights Commission, Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG), Korean Air and Korea Land & Housing Coporation (LH) sign an agreement (selling the site to LH, then exchanging it with SMG-owned land)

Nov. 10, 2021 Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism selects Songhyeon-dong as the site for the Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) and sign an agreement with SMG

Dec. 22, 2021 A coalition of civil groups hold a press conference opposing the rushed construction of the Lee Kun-Hee Museum

Oct. 7, 2022 The Songhyeon-dong site is temporarily open to the public as Open Songhyeon Green Plaza for two years

May – Oct. 2023 Part of the 2023 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism was held on the Songhyeon-dong site

Nov. 2023 The Rhee Syngman Memorial Foundation requests SMG’s mayor Oh Sehoon preserve part of the site for a memorial building

July 12, 2024 ‘Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) International Design Competition’ is announced

Oct. 24, 2024 Winning design for ‘Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) International Design Competition’ is announced

2027 Completion and opening of Songhyeon Cultural Park, underground parking lot, and Lee Kun-Hee Museum

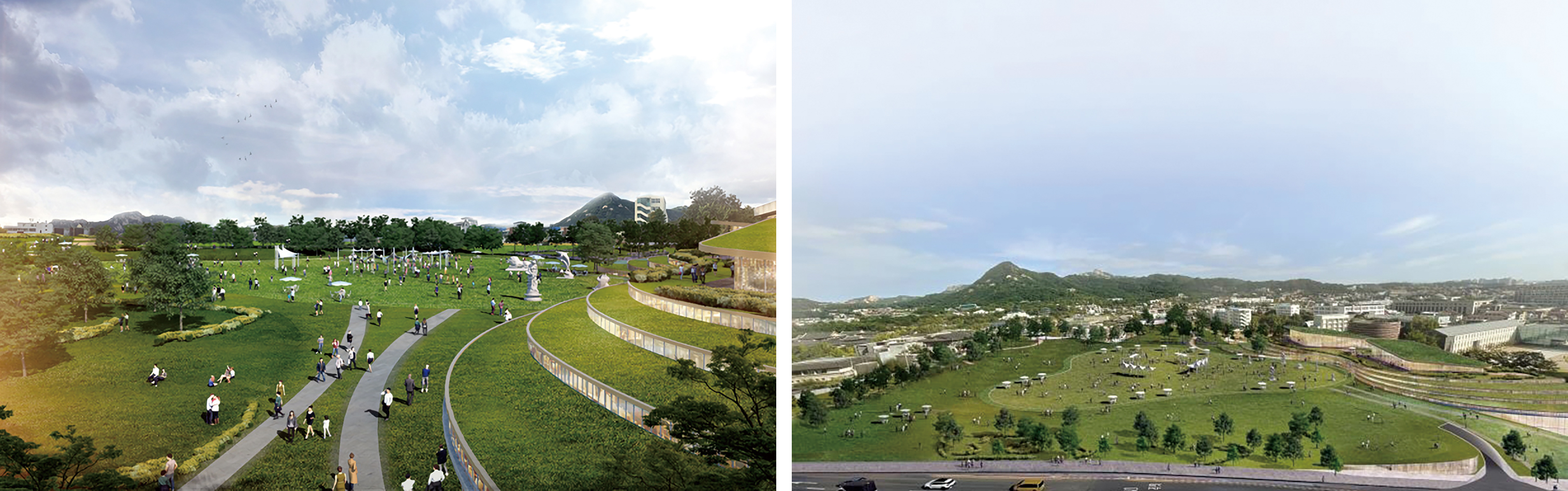

Rendering images of Songhyeon-dong site example by Seoul Metropolitan Government (2022) Image courtesy of Seoul Metropolitan Government

Why Is a Building Being Constructed on the Songhyeon-dong Site?

Before discussing whether the Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) is well suited to the Songhyeon-dong site, it’s important to consider whether the decision-making process was conducted properly.

The Songhyeon-dong site is the last large-scale undeveloped site left in the middle of Seoul. It is positioned in a key historical and cultural tourism zone, with Seochon, Gyeongbokgung Palace, and Changdeokgung Palace to the east and west, and Bukchon Village and Insa-dong

to the north and south. Nearby are a range of museums, including the Seoul of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Art Sonje Center. After ownership by a private company in 2000, the site remained undeveloped due to local government regulations. In 2021, just eight months after Seoul Metropolitan Government purchased the land from Korean Air, it was ironically designated as the location for the Lee Kun-Hee Museum.

The local government weighed two options: the Songhyeon-dong site and Yongsan site, ultimately choosing Songhyeon-dong site due to its proximity to cultural tourism infrastructure. However, this site analysis only compared which location would better accommodate the Lee Kun-Hee Museum; it didn’t consider whether constructing a building on the Songhyeon-dong site itself was appropriate.

At the time, a coalition of civil groups opposing the rushed construction of the Lee Kun-Hee Museum pointed out the lack of public participation and involvement in the decision-making process, and criticised the evaluation for being driven by economic ripple effects and the goal of boosting Korea’s image as a cultural powerhouse. Despite this, their concerns didn’t gain significant traction.

What direction did the project take after the decision to build was reached? In July 2024, the local government launched an Lee Kun-Hee Museum (tentative name) International Design Competition, but it focused solely on the plot ringfenced for the museum, excluding the rest of the Songhyeon-dong site, and invited only architects, excluding landscape designers. This raises questions, especially considering that in 2012, the Hanok hotel plan by Korean Air was essentially rejected, with public interest and green space cited as reasons for the purchase of the land. In response, a group within the architectural community, the Korea Architects Institute, issued a statement calling for ‘greater transparency from the judging panel to ensure fair public architecture’, but they focused only on the fairness of the judging process, not the broader vision for the site, which is a missed opportunity. If even self-reflective voices the architectural institute that have spoke out the is not addressing the project itself and its direction, the burden of judgment and action falls entirely on individual architects. For example, in May, an invited architect in the Nodul Global Art Island International Design Competition rejected the invitation, indirectly expressing a desire to preserve the current state of Nodul Island. Similarly, some architects are likely opposing the current situation by simply choosing not to participate in this competition. For architects who see this as a crucial opportunity, their colleagues are left to take a more passive, subdued stance. The problem here is that their voices remain beneath the surface and never come together.

The ‘Publicness’ and ‘Parkification’ We’ve Overlooked

When we consider the actions of the local government, citizens, and architects, it becomes clear that the Songhyeon-dong site is being shaped by the local government’s desire for development, without sufficient input from the public or careful thought from the architectural community. In the rush to push forward in a different direction with their vision of ‘publicness’ and ‘parkification’, what essential elements have been missed?

Cho Junggoo (principal, guga urban architecture) expressed concern, stating ‘It is a site for citizens arrived at with some difficulty following the twists and turns of modern and comtemporary history. However, according to the current plan, it seems that even the remaining parks are likely to be repurposed into underground parking lots or outdoor exhibition spaces, ultimately becoming subordinate to the Lee Kun-Hee Museum.’ And he emphasised, ‘I sincerely hope that we can all enjoy the magnificent original landscape of Seoul, starting from Inwangsan Mountain, passing through Seochon, Gyeongbokgung Palace, Bukchon Village and reaching Changdeokgung Palace and Naksan Mountain, all on this cherished land.’ According to the competition guidelines, the underground parking lot is expected to accommodate 400 regular vehicles and 50 buses. It also requests that the planned parking area and the museum’s lobby are connected as public pedestrian pathways. Additionally, the Songhyeon Cultural Park, allocated for the park site, has been left open to be developed as outdoor exhibition space for the Lee Kun-Hee Museum. As it stands now, Songhyeon Cultural Park is likely to function as a front yard for the museum, and the Songhyeon-dong site is expected to become a ‘public’ space focused on tourists, cultural figures, and vehicle users. Yes, public spaces need to offer different kinds of facilities, but some choices shape a place’s character, turning it into something not everyone can easily access. It’s important to remember that for many, public spaces are only truly public when they’re free—places where there’s no charge for a cup of coffee or a ticket. The scope of the public, including class, minorities, gender, and flora and fauna, varies depending on individuals and the era, and the role of a park is related to the context of the land. Therefore, achieving a social consensus on whose park this land will serve and what roles its facilities will fulfill is of utmost importance.

Look at Tapgol Park. In the aftermath of the 1998 financial crisis, the number of elderly men living in poverty soared, and the park became a hub for them. Or take Sinchon Park, behind Hyundai Department Store Sinchon. In the 2000s, it was an offline gathering spot for young lesbians who, until then, had only connected online. And today, Gyeongui Line Park is a meeting place for menhera youth. In each of these cases, people on the margins of society gathered in vacant spaces, giving these places a unique identity. What’s important here is not just that the park becomes a refuge for those marginalised in society, but that citizens can naturally gather on this vacant land, thereby forming the identity of the place. However, in today’s world, where the capitalist machine is constantly running, examples like feel almost like a fantasy.

View of Songhyeon-dong site during the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2023 (2023) ©Youn Yaelim