SPACE November 2024 (No. 684)

On the 30th of August, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the Korea Craft & Design Foundation announced that the ‘Omok Park Renovation’, a collaboration between Yangcheon-gu Office, Seoul-si, design studio loci (principal, Park Seungjin), and moss architects (principal, Kim Heejung), had been selected as the grand prize winner (Presidential Award) in the project category of the 2024 Korea Public Design Awards. On the 1st of October, Park Seungjin, Kim Heejung, and Ohn Sujin (team manager, Landscape Planning Division of Seoul Metropolitan Government, and former director, Parks & Landscape Division of Yangcheon-gu Office) were interviewed at Omok Park to explore the decisions informing the project, from the design competition in 2021 to its present manifestation from the perspective of public design.

_

The question, ‘Where is your park?’ appears at first glance somewhat paradoxical. Can there be ‘yours’ and ‘mine’ when it comes to a park, one of the key public services? Over the past decade, the importance of public spaces and the extent to which they are intimately tied to our daily lives has been underscored by a range of institutional projects. Meanwhile, societal shifts have placed increasing value on individual experiences; this was particularly acute during the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic and its required social distancing, prompting discussions about the proper use and value of parks. Parks, which offer the opportunity to connect with nature in an urban landscape, are open 24 hours, and do not discriminate visitors based on identity or intended use, are more accessible than any other public facility. Thus, hospitality and the diversity of experiences that parks offer between ‘me’ (individual) and ‘us’ (community) places them at the forefront of the public realm. The colonnades and single-person benches that appeared in Omok Park after its renovation and reopening last December presented countless possibilities for new encounters between the individual and the community.

corridor lounge and courtyard

forest lounge

New Towns and Parks: Facing Change Once Again

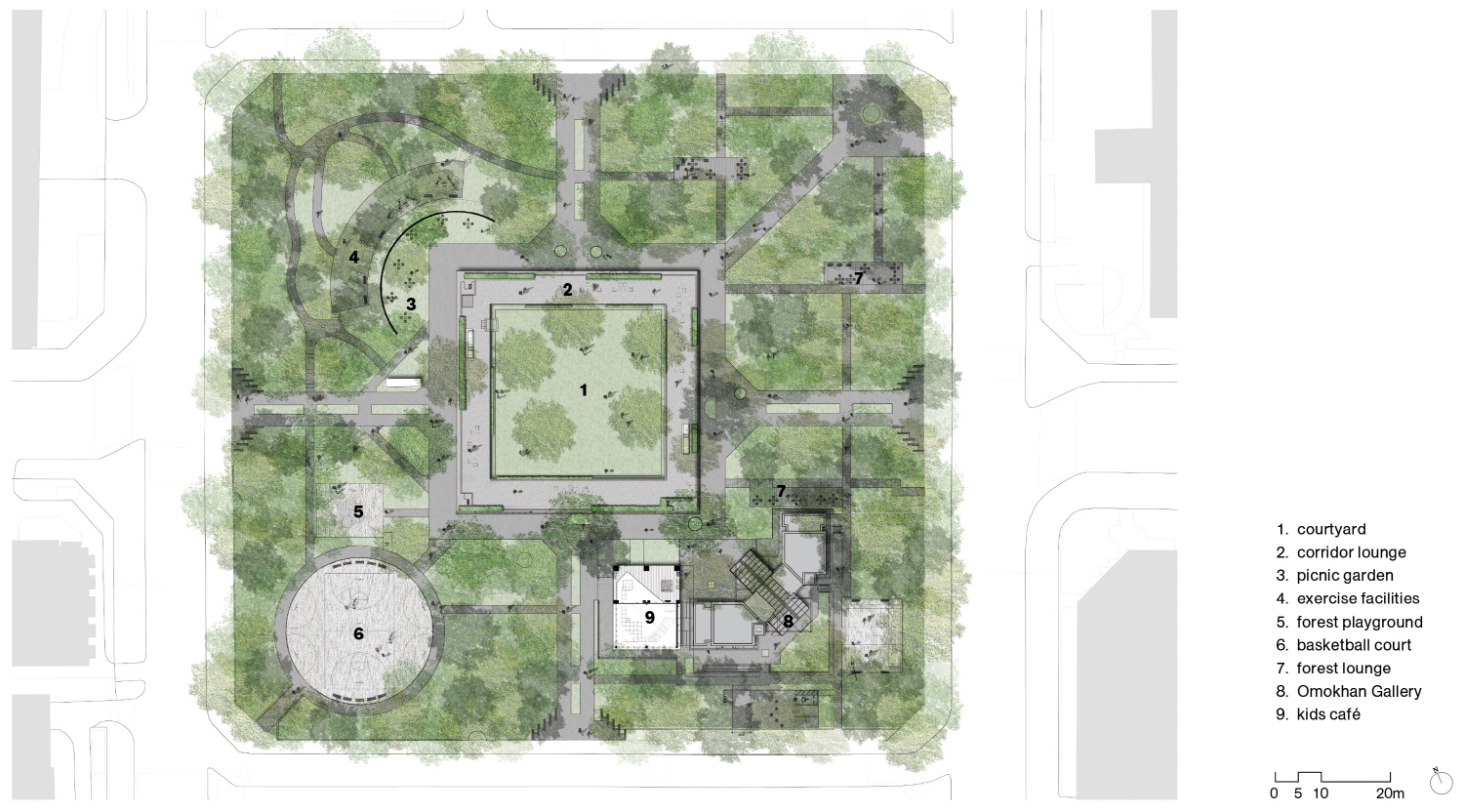

Omok Park, situated in Mok-dong, Yangcheon-gu, Seoul, sits at the central axis between five parks (Mongma Park, Paris Park, Omok Park, Yangcheon Park, and Sinteuri Park) that were established alongside the Mok-dong New Town, which was developed during the 1988 Seoul Olympics. It is surrounded by businesses and commercial facilities such as broadcasting centres or the mall, and therefore the park is frequently visited by not only by local residents but also by office workers. With future redevelopment plans for the Mok-dong complex, the population is expected to more than double, and there are also plans to transform the Gukhoe- daero to a park and develop a nearby reservoir site. Opened in 1989 and following the street formation, Omok Park is arranged in a square shape with dimensions of 150m on each side. As is typical of parks in new towns built on converted farmland, large trees planted on mounded earth around the perimeter have grown into a dense forest over the past 30 years. A sunken plaza and a wall fountain have also been introduced, while exercise equipment has been scattered between the forest and the plaza. Aware of relatively low usage rates compared to other parks in Yangcheon-gu, and faced with imminent urban changes and evolving demands from the public, Omok Park required a significant overhaul to meet these challenges and encourage new users to this space.

The corridor and courtyard were terraced so that people could use it as seating. The corridor's aerial walkway can accommodated several activities, such as pop-up stores.

site plan

Urban Public Lounge

Whether it is the renovation of a building or a park, the starting point for any renovation project is the decision of what to keep or what values to introduce. From the perspective of the landscape architect Park Seungjin, who led the overall renovation design, the park was initially devoid of undergrowth between the tall trees and had an insufficient number of benches to rest in the shade. The central plaza was sunken and therefore overlooked or circumvented by visitors, while pedestrian paths were unnecessarily wide. ‘The thought of a perfect awning under which visitors could comfortably stay and avoid the rain led to the idea of a corridor that would place a roof over half of the large pedestrian path.’ This is how the core concept behind the park, Urban Public Lounge, emerged. People come to the park without a specific purpose, staying alone or coming with others, and therefore Park thought that instead of fixed benches, it would be better to introduce single-person chairs that could be moved around freely. The chairs come with tables. On the table, one can place a lunch box or a laptop. In this way, it is a lounge—a space where people can comfortably stay, either alone or together. Rattan chairs were placed where they would be protected from the rain by the roof of the corridor, while metal chairs were placed outside of this covering. ‘It is not just any ordinary park seating, but a small luxury to arrive at a premium lounge chair and relax in a park.’ In fact, the original inspiration for portable park chairs came from the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. The city of Paris specially commissioned Fermob to create lightweight, stackable chairs for the garden. New York City’s Bryant Park, once infamous for drugs and prostitution, also succeeded in its renovation by placing Fermob’s green aluminum chairs. There is also a history of portable chairs in Korean parks. When Park participated in the design of Seonyudo Park during his years at Seoahn Total Landscape Design & Consulting Group, he drew upon teak chairs, and enjoyed watching users placing the chairs where they wanted. Although the chairs were eventually fixed due to maintenance issues, Park feels that seeing the chairs well-used in Omok Park is a sign that public design experiments in park culture, conducted together with its citizens, are finally bearing fruit.

The previously well-used basketball court has been maintained and renovated.

The corridor in the centre of the park

A Three-Dimensional Use of the Park

The central lawn courtyard was elevated from its original level to promote easier access. With the exception of a few trees transplanted from the corridor area, the area has been left open to serve as a plaza for various activities such as playing catch, performances, or flea markets. The outer forest area was enhanced with undergrowth and fitted with wooden decks raised slightly above ground level, serving as both pathways and rest areas (forest lounges). The corridor is an artery connecting all of the paths running through the park and becomes the central space for activities. Thus, the structure of the park is one of layers, like the layers of an onion, with the corridor separating the rectangular central courtyard and the outer forest. The square-shaped corridor has sides measuring 50m, a width of 8m, and a height of 3.7m. The roof of the corridor is used as a circular walking trail. The initial competition design only included a small observation deck on the corridor’s roof, but Ohn Sujin suggested the idea of using the corridor roof as a walking trail. The idea was to extend the narrow walking paths for when more users visit the park, after observing the walking trends at nearby Yangcheon Park. This three-dimensional use of the corridor provides another perspective to visitors as they overlook the forest. At present, there is a gardening centre and additional areas for reading in the indoor spaces of the corridor. The transparent ground-level indoor spaces have been separated from the structure in prefabricated fashion. Architect Kim Heejung explains that the indoor spaces and programmes can be flexible and changed whenever, both visually and practically. Temporary structures can be installed for special events such as pop-ups or local markets. If connected with the inner lawn courtyard, this area may transform into seating for a performance or an outdoor exhibition space. Kim further explained that efforts to enhance the completion of the park, such as constructing indoor spaces distanced from the corridor ceilings, or filling of concrete to prevent hollow sounds, are closely tied to cost issues, and credited Yangcheon-gu Office for their fully understanding design intentions. Ohn prioritised areas that received most attention from the designers when it came to the budget allocation, while securing additional funds through donation. Although receiving corporate sponsorships for renovation projects can be challenging, they were able to secure such support by successfully conveying the environmental and social significance of the project.

There are single-person benches and tables that can be moved freely throughout the corridor.

The building that was used as a management office and woodworking shop has been remodeled to create the Omokhan Gallery, and a kids café has been built here. ©Kim Jaekyeong

Continuing Community Memory

A hundred explanatory scenarios were added to the masterplan design that Park and Kim submitted during the Omok Park design competition. These scenarios ranged from ‘a woman in her 20s sitting on a park bench looking at SBS after failing her final interview at CBS’ to ‘high school girls pondering which donut to buy from a food truck’, from ‘residents settling down in the lawn area at 6PM to enjoy a small concert’ to ‘an office worker in his 40s reviewing meeting materials in the garden on his way to work’. Park Seungjin says he conceived of 100 such characters and their stories while imagining who might use the park. He reflected, ‘Isn’t a park a place in which such people gather? Because it’s open to everyone.’ From the streets, the park lined with trees looks familiar. The entrance where the park meets the street and the semi-circular rest pockets were all preserved in their original forms. Only a modest concrete boundary, that also serves as a bench, has been added to encircle the park and to provide a resting place for pedestrians. Elements preserved from the original park include not only such physical elements but also the memories of its users. During our visit to the park, we noticed a number of elderly people gathered under the steps of the corridor playing baduk. Ohn noted that they had been playing baduk at Omok Park prior to the renovation. Initially, they couldn’t find a suitable spot in the newly polished park but have now found a quiet corner. Personal stories cannot exist in isolation. While the elderly men playing baduk have their own individual lives, their activities in the park also reflect broader societal pressures in Korea, such as its aging population, generational conflicts, leisure culture, polarisation, and welfare. Individual memories converge to form collective memory and history. The public space that citizens experience is unrelated to the boundaries placed by design practice or academics, such as landscape architecture, architecture, or industrial design. This is why an integrated public design perspective is needed. It remains to be seen how Omok Park, regenerated by various experts with an understanding of each other’s fields of design expertise, will enrich and continue a prosperous community experience.

At the corner of the corridor, an indoor space has been created by separating it from the primary structure.