SPACE October 2024 (No. 683)

‘I am an Architect’ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

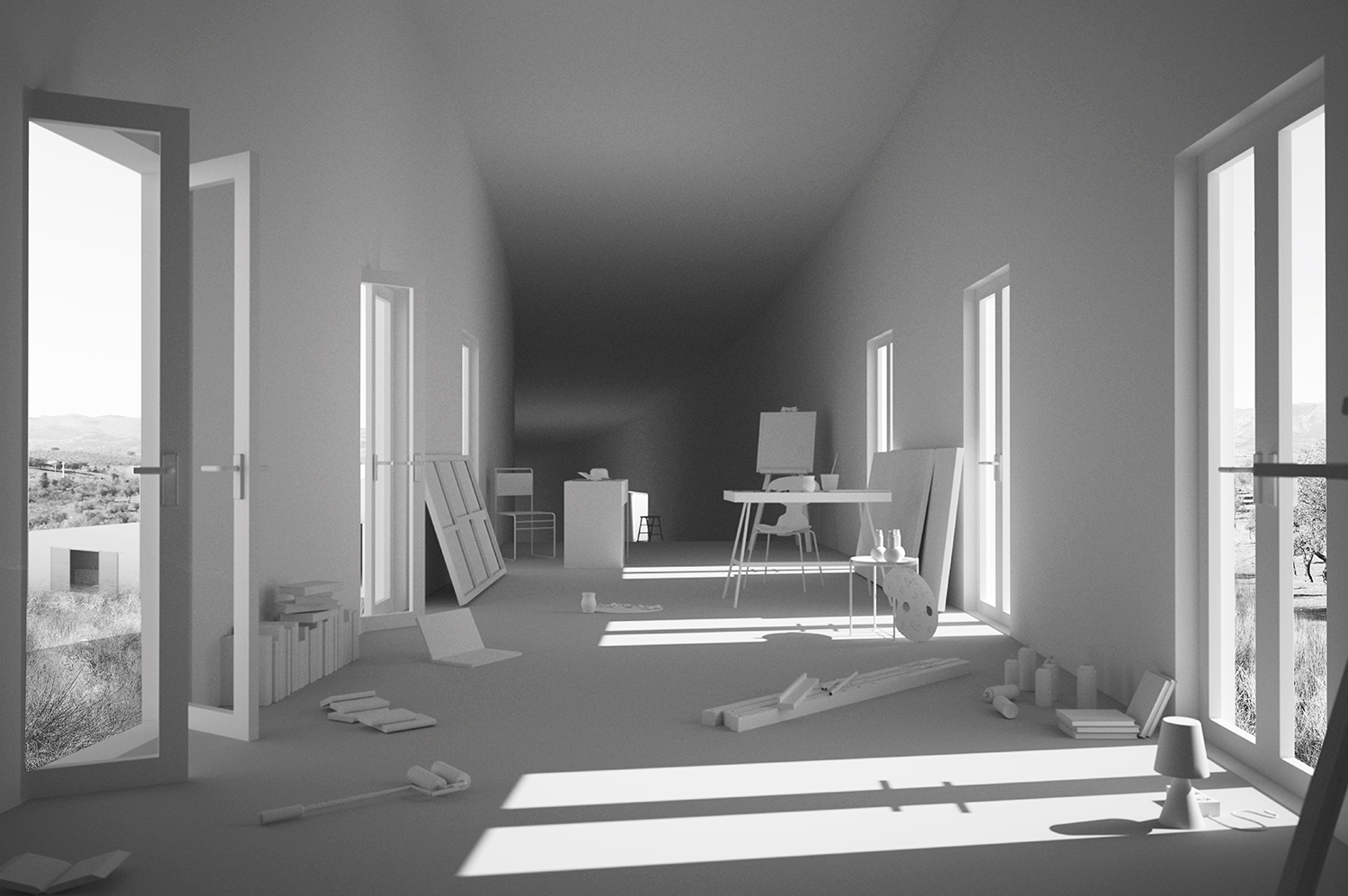

Endless Room worked at Royal College of Art

interview Park Taewon ARUP seniar architect × Kim Bokyoung

To a Bigger World

Kim Bokyoung (Kim): How is your life in London?

Park Taewon (Park): I visited the Serpentine Gallery multiple times since it opened in July, and I am now looking forward to visiting the park of the Natural History Museum. I have been here in London for 9 years now, but I think I am still in the adjustment phase—particularly in relation to the weather. (laugh) I mean, the weather changes multiple times within the day! I have mostly been working on international projects, so it has been quite hectic. Nowadays, family time is my favourite pastime. We held a party some time ago to celebrate my child’s second birthday.

Kim: What brought you to study in the U.K.?

Park: After graduating from college and working at a design studio, I started having some doubts about what I thought could be taken for granted regarding architecture and design. Specifically, I felt that I needed to reflect on why I often emphasised certain things and why I preferred certain designs over others. And I wanted to share these reflections with people from all over the world. Since London is home to many international architects and artists, I wondered why not start there. So, after my wife and I got married, we spent our honeymoon in London so that I could visit the schools and see for myself if the rumors were true. Even then, London was perfect except for the weather! (laugh)

Kim: There are many schools famous for architecture in London. Was there a particular reason why you chose the Royal College of Art (RCA) among them?

Park: During my studies and work in Korea, I felt that – as an architect – building professional connections and participating in collaborative experiences are important. I mean, aside from forging ties with other architects, I found forming connections with people outside architecture to also be very important. And so I concluded that I should go to an art school rather than a school only for architects. Also, instead of focusing on things like technicality, visual quality, or the end results, the RCA emphasises historical methodologies and the architect’s social self-awareness. As such, the RCA is also open to people who wish to enroll without a college degree in architecture. Many RCA graduates became curators, artists, and critics instead of continuing in architecture. I don’t wish to overgeneralise, but I think the RCA is relatively more open than other architectural schools.

During my studies at the RCA, I had the chance to collaborate with multiple artists with whom I still keep in contact. One example of this collaboration is the CASA NA BARRINHA: Artist Studio House in Brazil which I did with Joao Villas – an artist and a congenial partner whom I met during my student years. We worked on the design together as students and turned it into reality.

A meeting at ARUP London Office, Park Taewon (middle) ©ARUP

Architect in an Engineering Company

Kim: Isn’t ARUP well-known as an engineering company? What are your responsibilities as an architect?

Park: You are right. ARUP is relatively better known as an engineering company that collaborates with star architects to realise designs like the Sydney Opera House, Centre Pompidou, and Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP). My role here is to represent the design aspect of ARUP. ARUP has its own architecture department, and I am currently working there as a senior architect.

Kim: I’m curious to know what led you to work at a company known for engineering after your architectural studies at an art school rather than at a local atelier or some star architect’s studio based in the U.K..

Park: Before joining ARUP, I worked for a while at an atelier named Stuart Forbes Associates. Stuart Forbes is a fellow RCA graduate who used to work with Richard Rogers at the RSHP as its principal architect. Perhaps out of fondness regarding my passion for design, he had me participate in his client meetings and design decisions. These were defining moments for me. Because of the long heritage and tradition of British architecture, it is rare to get a chance to introduce new architectural designs in the U.K. It is already a major event to get a chance to build something new. These experiences led me to realise that I needed to look beyond the local U.K. scene if I wanted to achieve my full potential and pursue what I want in terms of design, and this motivated me to look for companies that work on an international scale. While the studios of star architects would undoubtedly provide many opportunities to become involved in projects of grand scales and to learn various skills, they also leave little room for taking initiative and crafting innovative new designs. And ARUP happened to be looking for an architect who is passionate about design to highlight its strengths in the design field alongside its established image as a professional engineering company. I could play a more proactive role in their projects and quickly respond to feedback in cases of conflict between design concept and structural difficulties. I think these are some of the major reasons that won me over to become an architect in an engineering company.

Kim: I heard you recently became the lead designer for the New Murabba Stadium. It was on the news in Korea. Congratulations!

Park: Thank you. The competition for the New Murabba Stadium invited various companies of famous star architects. Before participating in this competition, ARUP conducted its own in-house competition. An idea that was developed in collaboration with an architect named Maggie Wang Zuniga was selected as the winner for ARUP’s in-house competition as well as the actual competition. The win is special because our team had high hopes for this project. Whenever we hold in-house competitions like this, we are given a lot of freedom in terms of forming our teams. Even if one already belongs to a team, if one is willing to spend the time and take up the challenge, one can also simultaneously lead other projects as well. It is as easy as emailing or calling up some professional in structural engineering in a branch office in Spain – someone with whom you once had a pleasant work experience – and inviting him or her for a new collaboration. And this became easier due to the Coronavirus Disease-19 crisis. I think this is one of the interesting strengths of ARUP. In 2010, me and my fellow newcomers to the company submitted a glass pavilion design to a pavilion competition after following through with a proposal made by a glass company, and it was selected as the winning design. Unfortunately, the actual construction was cancelled due to the pandemic.

Korean Pavilion, Ieum ©Lee Eunyong

Pavilion O ©Lee Eunyong

Desire to Connect and Explore

Kim: You are also involved in many other activities aside from your work at ARUP. How did they come about?

Park: I think I am still driven by the desire to question and learn. Company work is mostly projects ordered by clients, so they are usually limited by the clients’ requests. While it is the professional’s job to work within these requests, however, I also have the desire to go beyond such predefined proposals and to question the fundamental methodologies and the essence of architecture. And I think it is important to connect with other architects and artists to accomplish that. During my time at RCA, I founded a group called Zero Lingual, together with architect Kim Ilhwan and curator Dr. Kim Stephani Seungmin. We still keep in touch by collaborating in competitions and projects. The name Zero Lingual is a humorous reference to the notion that if you try to speak both your native language and English, you’ll end up speaking neither language well. At the same time, it reflects our belief that by refusing to be defined into a single category, one can better grasp the essence of the culture, architecture, or art of foreign countries. Thanks to architect Nettie, a fellow member of Zero Lingual, I am also collaborating as a research designer at NIII SPACE. We were classmates of a studio class at the RCA, and we once co-designed a Chinese house. It was a renovation project for a property owned by Nettie’s parents. This building was a New Chinese style house that was printed out like apartments by using a traditional Chinese house as base template. We began this project by critiquing the practice of spatial production that relies on copy-pasted forms and templates. By asking fundamental questions such as what the daily cultural habits of Chinese people are and what kind of space would reflect such habits, we stripped off all ornamental elements from the template to demonstrate that cultural habits do not reside in mere template forms and outward expressions. Our project encourages contemplation of the notion of cultural authenticity and the essence of a home as a sanctuary of sincerity and comfort. At the same time, I personally designed Pavilion O and Korean pavilion, Ieum in Korea. These were design competition projects on which I collaborated with TEAM.SEOHWA (co-principals, Do Yeony, Kim Sungwoo) whom I got to know from Zero Lingual while working on an exhibition space design.

Kim: What is the biggest difference between company projects and personal projects?

Park: The biggest differences are the finances and time. Because pavilion projects, for example, was a public project, we had a tight budget. And yet we also had to consider the costs of installation and demolition within that budget. It was challenging. But I think it also led us to be very deliberate in terms of selecting the architectural elements. Architectural elements tend to add up recklessly when working on spectacular projects with multiple programmes such as the Murabba Stadium. Also, it was nice to work on a project that has a more grounded connection with the public.

Kim: What do you mean here by architectural elements?

Park: Pavilion O was a project that explored and reflected on the concept of the corridor. During my time as a student at the RCA, I became interested in the potential of corridor spaces. A corridor is not merely a passage connecting rooms, but an infinite space with its own unique function. In Pavilion O, I wanted to create a space where visitors could isolate themselves from the park’s flow circulation to reflect on the historical tomb and oneself. I aligned the corridor space to the natural ridge and turned it into a continuous circle. I then allowed a tiny bit of light to seep in through the ceiling and the floor so that visitors would walk in it while looking at either the floor or the sky. In Ieum, I explored the pillar element. It reflects my thoughts on themes such as, can pillars be more than just a straight vertical line, and can pillars function as façades that express Hangeul’s geometrical property while also performing structural roles. I always focus on the composition of the space created by the element before the form. This element-centric interest was developed during my time at the RCA. My work at the RCA also became the motif for the pavilion.

Rendering image of New Murabba Stadium ©New Murabba & PIF

Yunlu house ©NIII SPACE

Looking for the Essence in the Unfamiliar

Kim: What are your future plans?

Park: My top priority is to work on projects in as many countries as possible. Space changes based on a region’s climate and culture, and through these diverse environments, I want to discover the essential elements that define the quality of space and architecture. I aim to explore the environments and architecture of different countries and identify the common threads that link them. I also aspire to become a lead design architect who isn’t confined to any specific discipline. By remaining a generalist, with limited expertise in areas like stadium design, I believe I can offer fresh perspectives while collaborating with specialists in those fields. My immediate focus is to work on as many diverse and meaningful international projects at ARUP as possible, while staying open to pursuing personal research or competition projects outside the firm. And I guess I will return to continue working in Korea sometime in the future.

Kim: What is your ultimate goal or dream as an architect?

Park: My dream is to live in a home that I personally designed. Doing things like searching for the essence of architecture and applying an element-centric design approach are all meaningful, but feeling for yourself what it is like to live in a building that is designed informed by such reflections must itself be meaningful. And perhaps, and hopefully, that experience might even bring me to a different outlook. Now that I think about it, maybe this does not sound like it should be an ‘ultimate goal’. (laugh)

Park Taewon, our interviewee, wants to be shared some stories from Han Jeeyoung and Hwang Sooyong (co-principals, LIFE architects) in December 2024 issue.

Park Taewon