SPACE December 2024 (No. 685)

Evolution Timeline Wall leading into the Evolution Garden ©Kendal Noctor

interview Keith Jennings director of Estates, Projects and Masterplanning, Natural History Museum, London, Edmund Fowles, co-principal, Feilden Fowels, Neil Davidson partner, J&L Gibbons × Youn Yaelim

This July, a five-acre site that had long lain dormant within the grounds of Natural History Museum London was transformed for the first time in its 140-year history. By renovating the existing western garden and the under-used eastern lawn, the museum greatly expanded its wildlife habitat area and added two modest buildings. Going beyond the simple concept of green space, the Natural History Museum London aims to help support ‘urban nature recovery’, embracing citizens, wildlife, and the entire planet. SPACE spoke with the Natural History Museum London team, architects, and landscape architects who led this project to learn how this newly opened nature in the heart of the city is coming to life.

Pond landscape in the Nature Discovery Garden

Youn Yaelim (Youn): The Natural History Museum London (hereinafter Museum) has newly opened a five-acre garden. The new garden is a part of the Museum’s Urban Nature Project. What are the specific aims of this Urban Nature Project, and what tasks were given to the architect and the landscape architect?

Keith Jennings (Jennings): There is a critical gap in understanding how nature in urban areas is responding to a changing planet, so through its Urban Nature Project, the Museum is creating new tools and techniques to study urban nature. As part of this, the Museum’s gardens have been transformed into an accessible, free-to-visit green space that will be a haven for people and wildlife, and a living laboratory that will make the gardens one of the most intensively studied sites of its kind in the world.

Neil Davidson (Davidson): The brief from the Museum was to create a design for the gardens as a response to the urgent need to monitor and record changes to the U.K.’s urban nature and to develop skills to study in this field, as part of a national drive to re-engage people with the natural world and urban wildlife. Alongside Feilden Fowles we had long sought a special project for both our studios to work together on. As architecture and landscape architecture studios our design ethos comfortably align and when the opportunity arose to submit a response we jumped at the chance.

Edmund Fowles (Fowles): The key aims of the brief given to the design team were to: ensure best-practice accessibility; increase biodiversity; create a space for our five million visitors a year to enjoy, learn about the past, present and future of life on our planet, and to explore nature that can be found on our doorsteps in towns and cities; create a space that responds to and celebrates the existing historic building, etc. We led the transformation of the gardens, working closely with landscape architects J&L Gibbons, and created the Garden Kitchen and Nature Activity Centre as buildings integrated within the garden.

Evolution Garden

Youn: The Museum consists of the original building by Alfred Waterhouse from the 1800s, along with the later additions of the Paleontology Building (1976) and Darwin Centre (2005), each with different architectural styles. How did you harmonise the different styles of these buildings with the new garden and buildings?

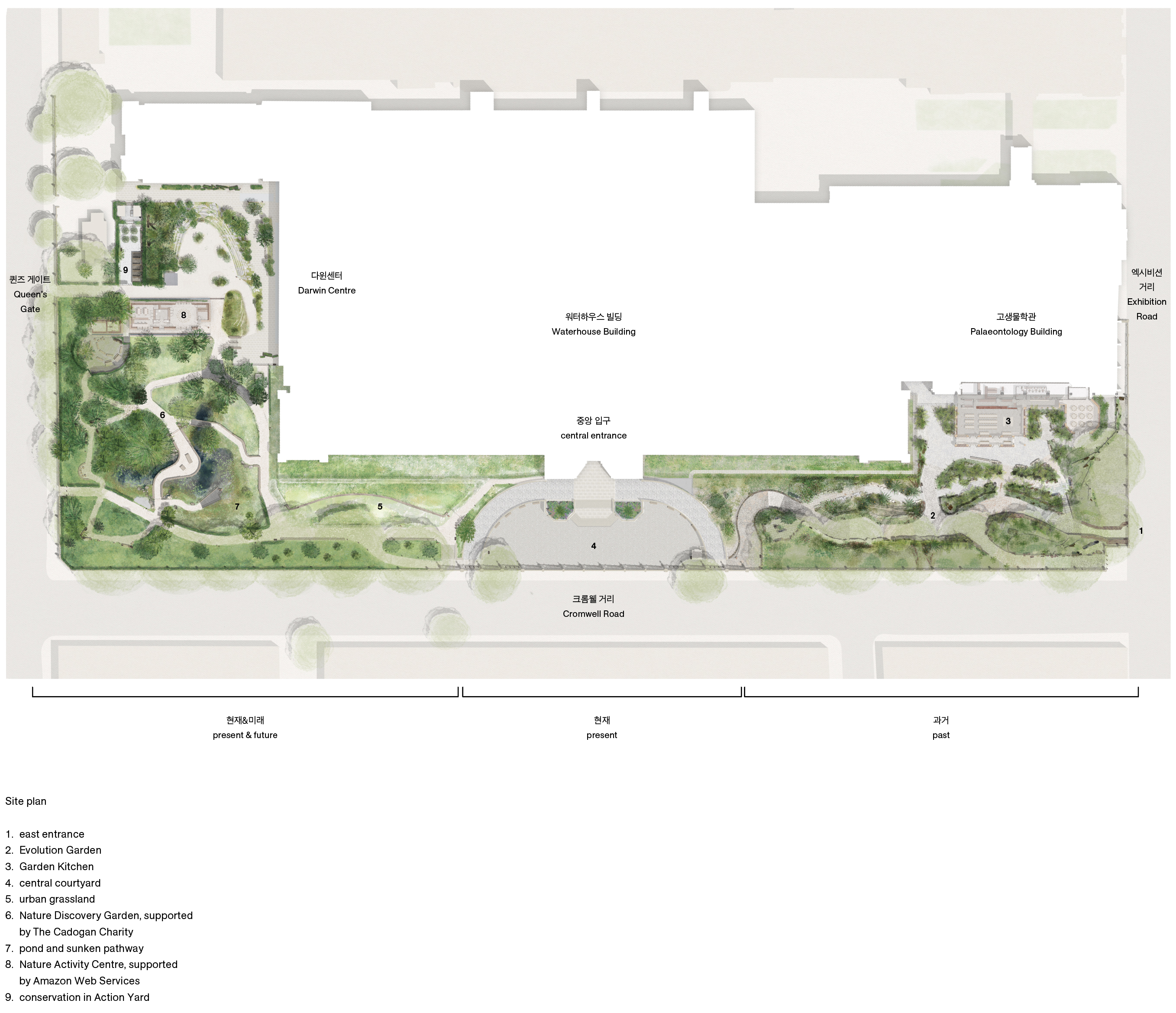

Jennings: Respecting the heritage of the Museum’s iconic Grade 1 listed building, designed by Alfred Waterhouse and dubbed a ‘cathedral to nature’, has been a core guiding principle. Waterhouse arranged the Museum with past (extinct) species in the east wing and present (living) species in the west. This idea is echoed in the thematic arrangement of the gardens.

Fowles: The building heights correlate with the datums of the Waterhouse Building, and key views of this 19th century landmark were carefully considered during the design of the Garden Kitchen, which can be seen from both Cromwell Road and Exhibition Road. Nestled into a previously under-used part at the north of the site between the Waterhouse Building and the Palaeontology Building, the Garden Kitchen matches the height of the plinth base of the Waterhouse Building and its back of house facilities are entirely concealed within the Palaeontology Building’s undercroft.

The Nature Activity Centre is reflective of the Directors’ Lodge, another Waterhouse-designed building on the western edge of the Museum’s gardens. The form is an evolution of Feilden Fowles’ own studio in Waterloo (2016), a building which opens out onto a garden. Topped by a pitched, timber framed roof that overhangs dramatically on the north and south, the Nature Activity Centre celebrates the capture of rainfall from the roof and provides a purpose-built covered space for learning about the nature on our doorsteps.

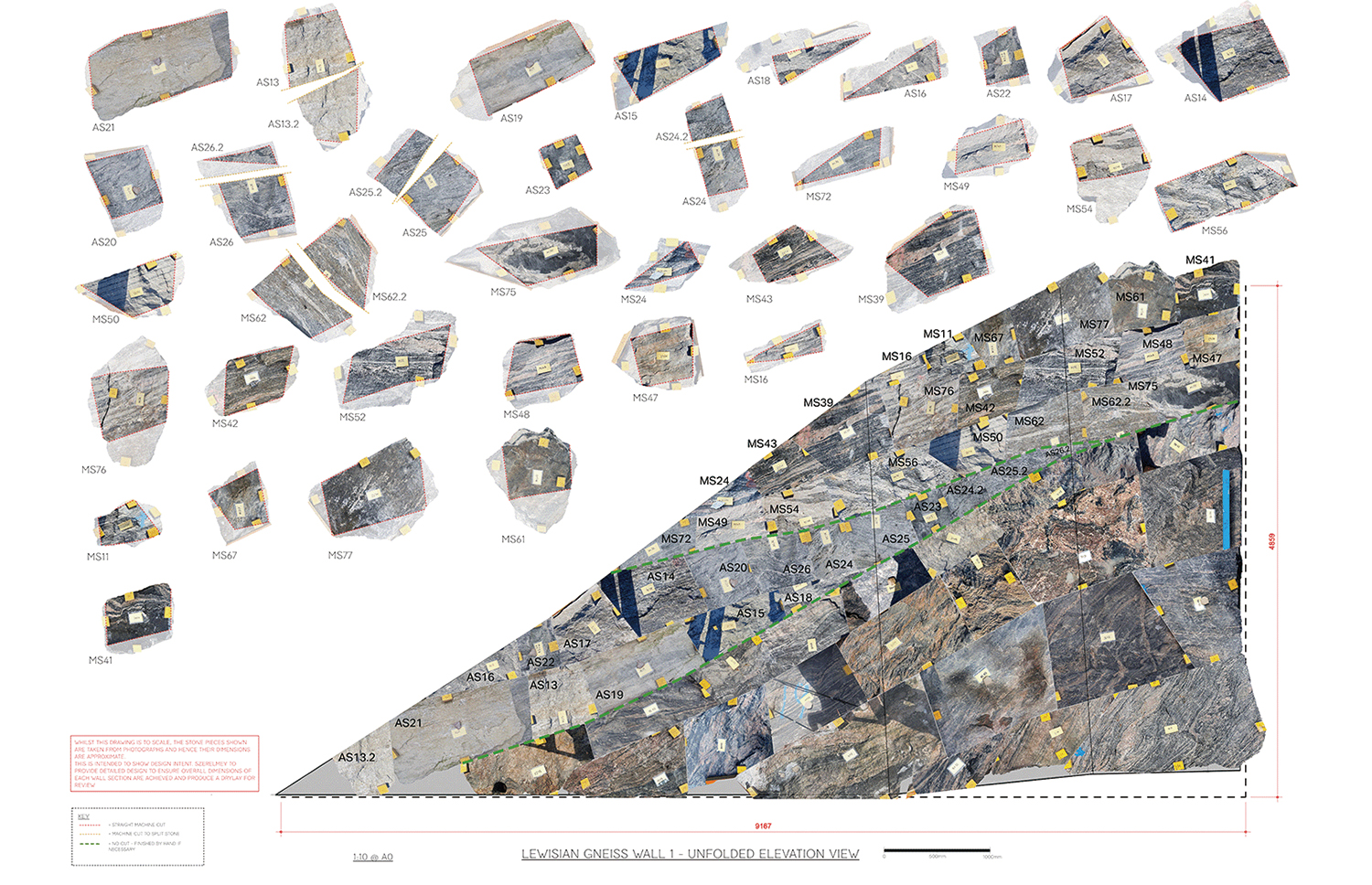

Lewisan gneiss stone layout of the rock canyon wall ©Feilden Fowles

Bronze Diplodocus cast named ‘Fern’

Youn: The two buildings were built using stone and wood to reduce carbon footprint.

Fowles: The two buildings were conceived as brother and sister, sharing motifs such as their linear plans, expressed corner entrances, layered, load-bearing stone façades and expressed timber framed roofs. This simple, primitive language is intended to be timeless and yet small flourishes of detail, such as rotated, and faintly ornamented corner columns are a nod to some of the more exuberant and witty decoration of Waterhouse’s masterpiece. The buildings are heavily crafted, intending to be at once solid, robust and grounded, whilst conjuring the language of simple rural vernacular buildings, very much in the spirit of Feilden Fowles’ ‘low-tech’ approach to architecture.

Jennings: This project was holistically planned and executed with sustainability at its core. It ensured a diesel-free, waste-free construction site, with all excess site materials recycled. Locally sourced natural materials, such as solid Douglas fir and low-embodied carbon limestone, were used to meet sustainability targets. Additionally, a comprehensive water strategy was implemented, including rainwater harvesting and the distribution of surface water to irrigate plants in the gardens.

Outdoor classroom in the Nature Discovery Garden

Nature Activity Centre ©Kendal Noctor

Youn: What are the unique characteristics of the east and west gardens, each designed with a different theme?

Fowles: The design concept across the gardens is inspired by the themes and organisation of the Waterhouse Building. Waterhouse’s famous façade boasts intricate decorations of flora and fauna, with extinct species on the east wing and extant (surviving) nature on the west. This organisational concept is reflected in the proposals for the grounds in which past, present and future nature are the themes of the east (Evolution Garden), west and Darwin Centre courtyard (Nature Discovery Garden).

Jennings: Dr. Paul Kenrick, a principal researcher at the Museum, worked with the design team on the Evolution Garden. The rocks are carefully positioned according to the geological period from which they were sourced, forming a scientifically accurate timeline. They are positioned so that from the Cambrian Period, every metre walked is the equivalent of 5 million years on Earth. The rocks can be seen in the rock canyon wall and they are also incorporated into the landscape in various ways, from individual large boulders, to benches and gravel mulch. At least 26 different rocks are used throughout the canyon and the rest of the Evolution Timeline Wall, representing different geological ages. All but two were sourced from across the U.K. These rocks include Lewisian gneiss that formed over 2.7 billion years ago, granites that tell of massive movements in the Earth’s crust driven by the formation and breakup of continents and limestones full of fossils that formed in shallow tropical seas.

The plants have also been carefully positioned to create a sense of place throughout the Evolution Garden, immersing visitors in their evolutionary stories. At the start of the garden, mosses and liverworts have a starring role in the Ordovician Period. Large tree ferns feature in an ancient coal forest of the Carboniferous Period. Flowers appear later in the garden to reflect their origin during the Cretaceous Period. A corner of the garden is devoted to the Eocene Epoch when London experienced a subtropical climate. ‘Fern’, the name given to a bronze life-size Diplodocus cast, takes centre stage in its own Jurassic garden, surrounded by ferns, Wollemi pines, dwarf ginkgos and cycads—plants all chosen to evoke the feel of a landscape in the Jurassic Period. Grasses and flowers in the daisy family feature towards the end of the timeline to illustrate the spread of grasslands during the Neogene Period. For other elements, creatures are represented in brass inlays in the paths and as bronze sculptures helping to tell the story of the evolution of life across 540 million years. Human footprints make their appearance at the end of the timeline.

Davidson: There are seats provided throughout the gardens. Some of these seats have been hewn straight from the geology of the era, such as cooked chalk and flint, Grampian granite or Purbeck limestone. The Nature Discovery Garden, showcases the broad range of present-day U.K. habitat types and approaches to climate adaptation set within an urban forest of the future. As part of the early stages of this project a comprehensive analysis of the existing mosaic of habitats was undertaken. This process helped establish an approach informed specifically by the site, as one entity, an ‘urban habitat mosaic’, to reflect the diversity of small pockets of created habitat that were thriving and could be enhanced through new interventions. A ‘habitat translocation strategy’ for relocating the original pond, wetland, grasslands and enhancement of the woodland and hedgerow habitats within the Wildlife Garden was prepared.

Listening funnels in the Nature Discovery Garden

Installing sensors in the gardens to gather audio and environmental data

Youn: Approximately 20% of London urban space is public green space. Among London’s numerous gardens and green spaces that decorate the city, such as Kensington Gardens and Regent’s Park, what new significance does this garden have?

Davidson: With the exception of Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens nearby, there is very little publicly accessible green space available in close proximity to the Museum. Therefore, accessible green space is greatly needed in the local community. The Museum grounds is now essential green space in the heart of South Kensington—not only as a place where visitors and the local population alike can relax or spend a lunch break surrounded by nature, but also as an important wildlife habitat.

Jennings: The gardens have been transformed into two outdoor living galleries ripe for exploration. The Museum’s aims are to help visitors gain a sense of the scale of geological time, to convey some of the great changes in Earth’s plants, and to draw connections between the evolution of life and geological processes. The Nature Discovery Garden is a space for visitors to find out more about the extraordinary wildlife right on our doorstep in our towns and cities. In this way, the gardens are supporting the Museum’s mission to create advocates for the planet. The gardens will also be the most intensively studied urban site of its kind, where Museum scientists and volunteers alike can develop best practices to support urban nature recovery. When it comes to protecting biodiversity, often all eyes are on woodlands and countryside spaces. However, studying urban nature can provide valuable insights into how wildlife interacts with our towns and cities and how it is responding to factors such as our behaviours as humans and climate change. This helps inform how urban spaces are managed, ensuring they safeguard and support biodiversity into the future.

The Museum’s partnership with Amazon Web Services (AWS) is integral to accelerating and enhancing this work. A network of 25 sensors across the Museum gardens will gather audio and environmental data. The calls of birds and bats, the sound of rain and wind, underwater sound recordings from the pond, as well as human-made sound such as traffic, will all be captured.

Wildlife in the garden

Youn: Urban Nature Project emphasises recovery of ‘urban nature’. When attempting to recover biodiversity, how should one’s approach differ between a high-density urban setting and a rural setting? Second, what method did this garden adopt for the protection and recovery of biodiversity?

Jennings: With the pre-existing gardens already home to important nature – Museum experts have recorded more than 3,500 species of animal, plant and fungus living in the Wildlife Garden since 1995 – the recent transformation of all five acres has been driven by an ambition to protect habitats and enhance biodiversity across the site.

The Museum’s Wildlife Garden was extended to double the area of native habitats within the grounds and the wetland area has been increased by 60%, with the aim of better supporting the gardens’ biodiversity. As part of the gardens’ transformation, the pre-existing pond was relined and excavated to add an accessible sunken pathway wide enough for two wheelchairs. The biodiversity of the pre-existing pond was preserved during construction by storing the original water and its wildlife in a temporary pond. Museum scientists closely monitored the water and its biodiversity throughout the entire process. The temporary pond thrived, and that very same water was then transferred back into the new pond area once ready. Plants such as water lilies, reeds and irises from the old pond have been re-planted. The pond has continued to thrive, with frogs, newts, dragonflies and mandarin ducks already spotted making themselves at home. In the Nature Discovery Garden, the different habitats showcase the rich biodiversity that can be found in the U.K.’s urban spaces. Woodland, grassland, scrub, reedbed, hedgerow and wetlands can all be found there. These are habitats that many people may find surprising to discover in urban settings.

Davidson: In a global context where more people live in urban environments than do not, the need to provide high quality and accessible green space and connection to nature is a prerequisite of good city planning and leads to the improvement of living conditions for city dwellers. The Urban Nature Project provides the opportunity to increase awareness and public engagement with urban nature, showcasing a variety of habitat typologies and techniques that can inspire projects in different locations.

The Urban Nature Project represents an inspiring case study for repurposing urban spaces to increase biodiversity and provide urban cooling, as well as offering recreational and wellbeing benefits and enabling scientific research. It is part of a national initiative aimed at inspiring people – and in particular young people – to develop a love for nature and become the naturalists of the future.

©Feilden Fowles + J&L Gibbons

©Feilden Fowles + J&L Gibbons