SPACE August 2024 (No. 681)

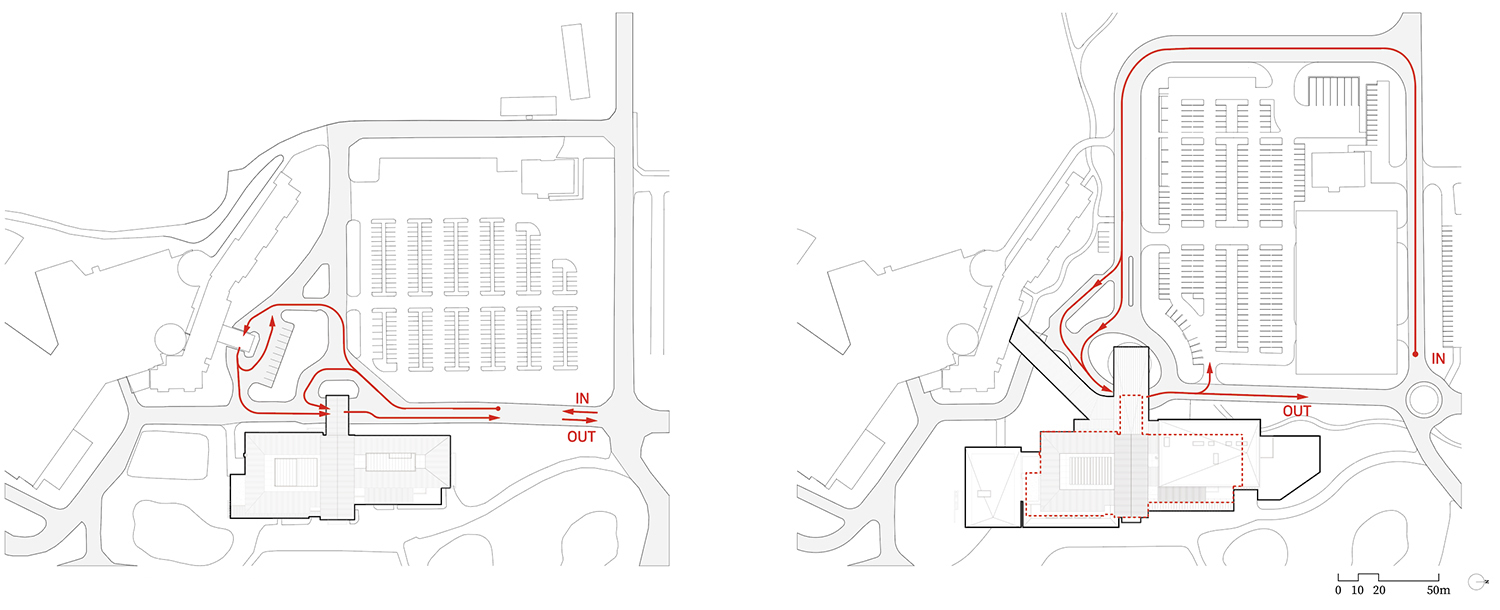

(left) Structural diagram of Seolhaeone Clubhouse Extension, (right) Site plan of Seolhaeone

There are two types of projects given to architects. One involves designing according to the predetermined use and capacity of the site, and the other requires creating rules and developing a plan from scratch, without any predetermined scope or usage. For an architect who has only been exposed to a site with a predetermined use and capacity, as in the former case, it can be a completely new challenge to establish rules for the site. Large-scale developments, unlike typical architectural projects, involve a considerably complex process of urban planning procedures. However, through these processes, architects can learn to perceive the potential value of the land and develop a new perspective through which to interpret the entire complex. Architects are capable of understanding and considering the entire process of transforming a site that is yet to be defined into a viable architectural area. This understanding of the process of land development is another challenge for architects, but it is significant in terms of being able to experience all the processes of development. This is because it allows architects to look at the entire process of business development not just at a single building, as well as the various infrastructure required in the planning of the complex, the relationship between buildings, and the possibility of expansion in stages.

If someone were to ask me the meaning of Seolhaeone, I would say it was a project that allowed me to experience the potential architectural and development possibilities of land from a site development perspective. This means, there was a shift from the architectural development of individual plots to a broader view of site development. I started my own practice in 2009 with a parking building project in Yongin. Since then, I have worked on a variety of projects of different scales and programmes, such as Namhae Cheo-ma House (2011), The Curving House (2012), Platform-L Contemporary Art Center (2016), Pergola of The Club at NINE BRIDGES (2017), Ulsan KTX Parking Complex (2019), and Eaves House (2019). In the early days of my practice, I mainly experimented with material combinations within limited budgets. However, Platform-L Contemporary Art Center provided an opportunity to work more in urban scale projects and implement various structural and mechanical ideas. However, all the projects mentioned were the ones that focused on solving problems on a site with predetermined conditions. Technically, most of the projects were of the first architectural type mentioned earlier, those with predetermined land use and capacity. The Seolhaeone project, which began in 2019, is distinctive in that the site conditions were not predetermined, but rather had the chance to be newly defined. Additionally, I was offered the opportunity to explore the direction and identity of large-scale complex development and delve into the detailed architectural development plan, overseeing the entire process as an architect.

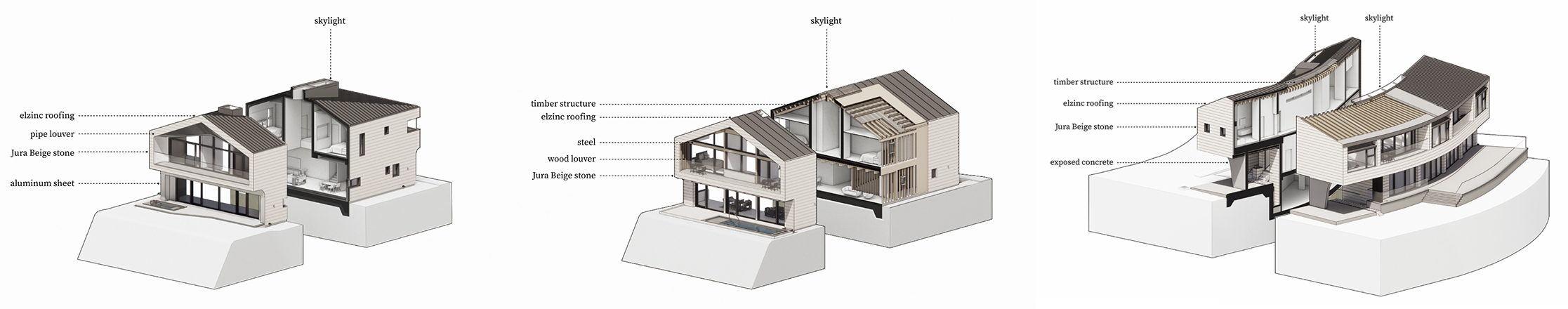

Sectional perspectives of Seolhaeone Clubhouse Extension

Seolhaeone Clubhouse Extension

The Seolhaeone project is a culmination of all the different types of projects I have worked on in my career so far. The Seolhaeone Clubhouse Extension (2022), for instance, was formally a remodeling project, but the actual process was no different from a new construction. In order to find a reasonable structural method for the required vertical and horizontal additions, various available construction methods were applied, including reinforced concrete (RC), steel reinforced concrete (SRC), steel frame, and timber structure. For example, the women’s sauna and locker room on the second floor is a vertical extension of the men’s sauna and locker room on the first floor, SRC was used as a method to minimise reinforcement of the existing structure and provide sufficient stiffness for long-span and vibration loads. This required ground reinforcement with grouting below the existing underground pit and strengthening the column cross-sections of the existing Clubhouse to secure the necessary column stiffness. For horizontal extensions, a new building was required for the Start House and the private dining room (PDR) expansions. Considering the connection with the existing building, these were planned using RC. Unlike the east side, which faces the golf course, the north side, which serves as the entrance to the Clubhouse, required a different gesture. A new image distinctive from the existing structural framework was necessary to connect with the existing Seolhae Hot Spring and establish a new identity for the Clubhouse. Therefore, dynamic forms and the mildness of the materials, which were markedly different from concrete and steel, were used to represent the spatial image that Seolhaeone aimed to projects.

Remodeling is based on structural and spatial complexity. It involves not only a rational extension system using the existing structure but also setting new relationships between customer and management circulation flow, upgrading and repairing existing mechanical systems, and considering future spatial expansions. Numerous administrative and technical aspects needed to be reviewed. Furthermore, in this project, in addition to the functional expansion of the Clubhouse, the connection with the existing accommodation facilities was also important. The relationship with Seolhae Hot Spring and the golftel on the west side aligned with the question of the Clubhouse’s role in the overall master plan. This required a circulation plan that provided convenient access for visitors while also considering non-golfing guests. The project also required a lot of consideration of the role of the Clubhouse as the central axis of the entire project based on its relationship with the future Seolhae Byuldam, Seolhaesoorim, and The Core.

(Left) Access circulation to the Seolhaeone Clubhouse (before), (right) Access circulation to the Seolhaeone Clubhouse (after)

Seolhae Byuldam

If the Clubhouse was a project based on systemic complexity, Seolhae Byuldam required an approach more akin to a housing complex. Unlike typical housing complexes that develop along various lines and patterns due to different owners, it was crucial for Seolhae Byuldam to guide a uniform architectural framework to create a unified landscape. The client did not want the site plan adjacent to the golf course to seem disorganised due to the diverse preferences and budgets of different landowners. In reality, the majority of housing complexes adjacent to the golf courses are built without principles based on the individual circumstances of each landowner, ruining the scenery of the golf course. In this sense, Type A, B, C of Seolhae Byuldam were multiple projects, which were 15 out of 20 units, and more of a master plan that sets the rules and principles for the entire complex. The problem was that the individual plots were not initially divided according to the current capacity and master plan. This indicated that the market conditions had changed significantly between the time the original complex was first planned and the time the new golf course was built. At the same time, it also meant that Seolhaeone had to find the optimal solution for the limited site while meeting the changed standards of the master plan. It was important to understand the market changes that occur in large-scale developments that are staggered in time, and to provide architectural alternatives that could respond flexibly to them.

Unlike typical housing designs that accommodate the needs of their users, Seolhae Byuldam was conceived as accommodation that intended to satisfy a broad range of unspecified customers. It needed to be universally appealing in the form of a housing while also serving as a key visual anchor for the golf course. Based on these criteria, the format and orientation of each type was determined. The architectural form that would dominate the entire landscape of Seolhaeone was the gable roof. By guiding the skyline with a consistent angle within the established maximum height, the aim was to create a unified development. Additionally, introducing diversity within these standardised forms allowed for a harmonious variety within the complex. For example, Type A is a RC structure with a triangular gable roof and a flat roof, while Type B is designed with a heavy timber structure where the form itself is defined by the structure. Type C employs a hybrid structure, mixing RC and heavy timber structure. Besides the diversity of types, it was important to study the combinations of types to generate synergy within the overall context of the complex. This means researching which type combinations would enhance the overall flow of the complex when developed consecutively on Seolhaeone’s plots. For example, Type A, a smaller unit, could be built as a separate building, whereas Type B, when two plots are developed consecutively, showcases the rhythmic quality of the timber structure more effectively. Thus, the types are arranged within the complex in a way that enhances the landscape based on their combinations. Based on these rules, Type C was built by merging two plots. The existing land was divided into small plots, and it was determined that it would be difficult to fill the actual capacity if developed as individual plots, so two plots were merged to create a larger workation space.

In this way, Seolhae Byuldam was a project aimed at optimising the advantages and combination possibilities of each type for the 20 plots owned by Seolhaeone out of the total 70 plots in the complex. The task required of the architect was not only to ensure the completion of individual buildings on each plot but also to overcome the drawbacks of the existing plots and complete the project with the most optimised combination within the entire complex. This project set the standard for the overall landscape of the complex in relation to the golf course and established the baseline for the other plots to be developed in the future.

Sectional diagram (Seolhae Byuldam Type A), Sectional diagram (Seolhae Byuldam Type B), Sectional diagram (Seolhae Byuldam Type C)

The Expansion of Scale and Perspective

An architect must acquire a wealth of knowledge and accumulate a diverse range of experiences. When I first began my practice, I focused on meticulous details and the relationships within spaces to ensure architectural completeness. As I experienced projects of various areas and scales, I became interested in how the district units that determine the ways plots are divided in urban planning and the methods for determining legal capacities, are constructed. Ultimately, it is about understanding how individual buildings come together to complete a complex and how these complexes form the urban fabric. This aligns with the question of ‘what space should be vacated and filled with’ the urban space that is created. In other words, it is a question of how to redistribute density and how to create relationships between necessary programmes. In this sense, the Seolhaeone project began with a consideration of the Clubhouse as a focal point in the context of the entire site and the future projects that would expand around it. It also expanded into a process of extending the area of developable land within the given volume of the tourist complex, redistributing the density of the constructable area, and interpreting it in a commercial context. Over the past four years, I have examined the possibilities of all the developable land in the Seoulhaeone site. Although it was not possible to plan all the projects that were reviewed, I had the opportunity to think deeply about the potential and possibilities of spaces in relation to construction. In this respect, the Seolhaeone project will be remembered as a work that allowed me to experience a new viewpoint and perspective on site planning, beyond the architectural scale.