SPACE October 2024 (No. 683)

a0100z (principal, Sung Sangwoo) is a studio that has focused on housing projects since its establishment 20 years ago. The architect’s inquisitive personality – which drives him to constantly interrogate the nature of houses, madangs (yards), thresholds, and floors, as well as questioning the essence of those he designs for – compels him to look beyond conventional moulds for a house. a0100z’s attitude toward houses is reflected in its principles: design work begins only after spending time travelling with the client and his or her family, and architectural photos of the finished building are taken only after a year has passed since its construction. The wooden house in a small town where the architect lives is filled with traces of people who became visiting friends after participating in his designs. By reviewing five of their housing projects in Daejeon, Sejong, and Geochang, Lee Kyungah (professor, Seoul National University) traces a0100z’s new interpretations and insights regarding interior and exterior madangs, combinations of standing and floor-sitting spaces, and wooden structures.

Study and porch with jjongmaru of Yeongchungjae. By utilising various meticulous combinations of floor-sitting and standing spaces, a0100z demonstrates new possible directions for housing design. ©Lee Hanul

Madang of Yeongchungjae. Yeongchungjae and Cheongudang represent the most conventional interpretation of madangs in a0100z’s houses. ©Lee Hanul

a0100z’s five new housing projects reveal the studio’s experimental forays regarding houses by showcasing its novel interpretation of madangs (yards), an unusual integration of disparate spaces, and an experiment on wooden housing in a time where concrete is mainstream. Houses are characteristically change-resistant. Because houses are deeply tied to actual living, they tend to follow what is habitually familiar and resist innovation. Despite such inflexibility, however, a0100z makes various proposals for a new kind of house.

The five houses that will be examined in this text are On Sill (2022) and POOM (2019) at

Hagi-dong in Daejeon; Yeongchungjae (2016) at Noeun-dong in Daejeon; Sangsangrak (2020) at Areum-dong in Sejong; and Cheongudang (2019) at Jangpal-ri in Geochang. I will study the experiments performed by a0100z in these projects and reflect on their significance.

Living and dinning room of Sangsangrak. A thick wooden beam that runs across the two-storey high space has exposed. ©Yoon Donggyu

Upper madang of POOM. A jjongmaru is attached to the madang, providing a place for contemplation while admiring the sky and the trees. ©Lee Hanul

Rediscovering the Exterior Madang and Experimenting with the Interior Madang

First, the madang that commonly features in a0100z’s houses draws attention. One defining characteristic of a traditional Korean house is the madang. Unlike the word jeongwon (garden) which possesses a more contemplative and static connotation, a madang designates a dynamic exterior space that embraces various aspects of life. However, madangs are difficult to find nowadays even in single family houses, let alone apartments. There is little room for madangs to be considered in contemporary housing projects in Korea where filling building to land ratio and floor area ratios via maximisation of floor space tend to be the main priority. In contrast, a0100z seeks to rediscover the value of madangs that are slowly becoming forgotten.

Out of the five houses, Yeongchungjae and Cheongudang offer the most conventional interpretation of a madang. These two houses resemble either the ㅁ-shaped or ㅂ-shaped hanoks that are built around their central madangs. The madang secures an appropriate amount of distance between each room and an exterior space that is privy to the family. In Sangsangrak and POOM, segmented madangs that are divided by differing ground levels were introduced. The madangs were divided into two or three segments, and each segment was designed differently with contrasting floor finishes and vegetation to demarcate their different purposes and acknowledge users. Still, the madang as a whole unites the house, acting as its centring space. Aside from central madangs, a0100z’s houses also feature multiple smaller madangs that are hidden around the site. One of them has a jjongmaru (narrow wooden veranda) attached to it to provide a place for contemplation while admiring the sky and the trees outside, while another acts as an elongated bamboo garden that adds a green-tinted shade to the adjacent room along with breeze and sunlight.

Of the five projects, the most adventurous form of madang reinterpretation is displayed in On Sill at Hagi-dong in Daejeon. An onsill (glasshouse) space which is positioned at the centre of the house functions as an interiorised external madang that is neither completely interior nor exterior. This two-storey high onsill functions as an axis that not only defines the eastern-western and higher-lower spatial dimensions of the house but also ties them together. Aside from connecting spaces, the onsill also connects the family members. The family members enjoy the intimacy of one another at the onsill as they spend time together reading, playing games, or watching movies in it. The onsill is also extended by its connection to the north-south madangs that have respectively contrasting personalities. While the southern madang, which is artificially elevated via a concrete cantilever structure, blocks out unnecessary views from outside to preserve the family’s privacy, it also directs the line of sight within the onsill structure and adds a sense of cosiness. The northern madang, which had its floor finished with stones and dirt that surround a small tree, blurs the boundary between the house and the natural ridge and invites the green scenery of the nearby mountain into the interior. In this way, the three madangs with respectively different characters and materials meld into a unified long madang to act as the house’s axis, and the onsill sits right at its centre. This onsill that appears at times like an open exterior and at times like a closed interior is a0100z’s new interpretation of the madang.

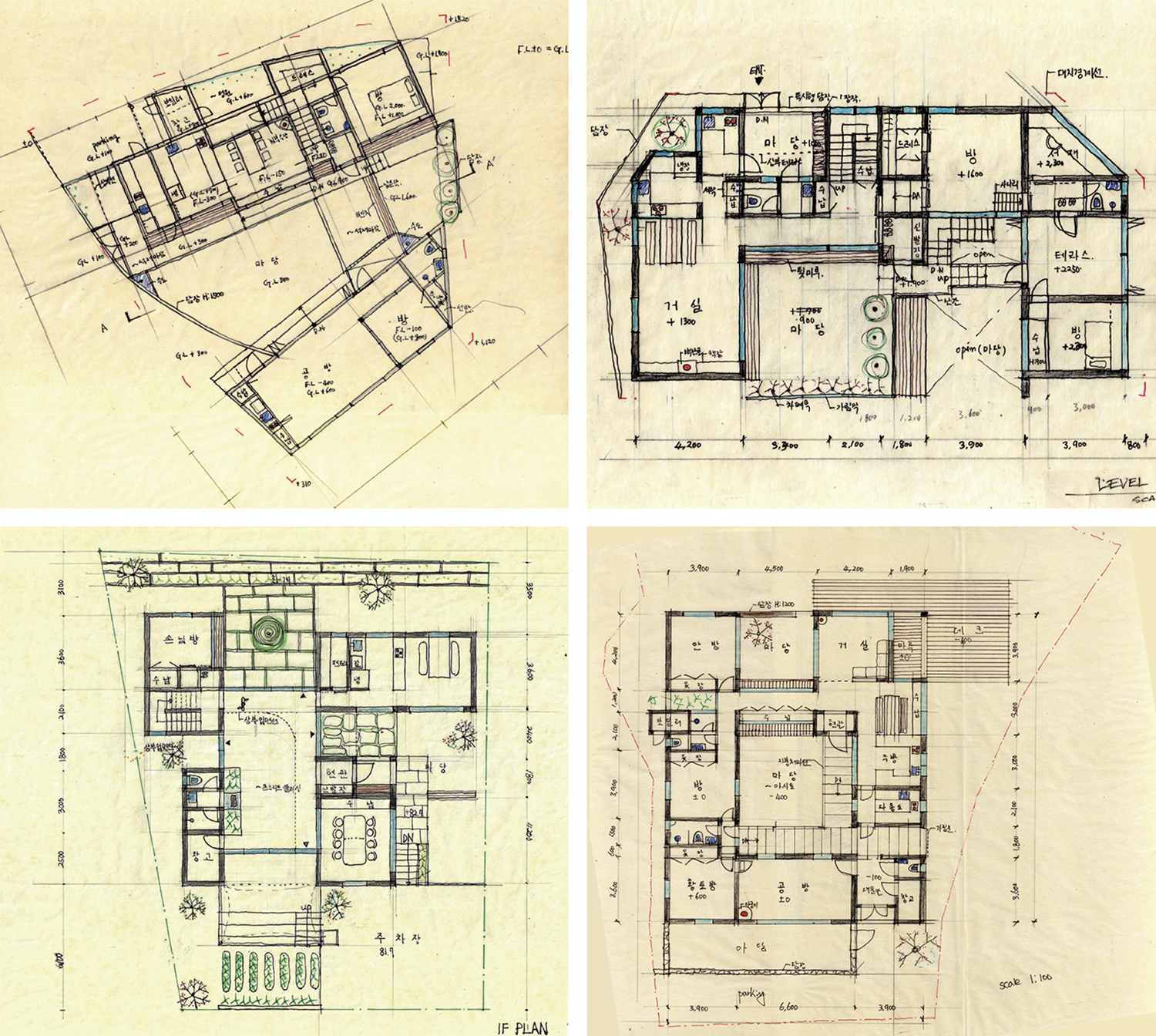

(in clockwise) Floor plans of Sangsangrak, POOM, Cheongudang, and On Sill

Different Combinations of Floor Seating and Standing Spaces

a0100z’s houses integrate spaces of different characters in various ways. Because traditional customs such as taking one’s shoes off indoors as well as the floor material choices and its heating system have evolved over countless corrections and adaptations over a long period of time, they are generally highly resistant to change. In that sense, it is very challenging to come up with a convincing way to integrate spaces that have long been defined by strictly different domestic roles such as floor seating and standing (which also includes sitting on chairs) spaces and private and semi-public spaces. However, a0100z offers various solutions to this.

First, in the case of On Sill, the piano practice room of the client’s wife is positioned near the house entrance as the representative standing and semi-public space. The centre onsill is a private standing space for the family, the first-floor dining room and the second-floor study are mixture types that offer standing spaces as well as floor heating, and the bedrooms have fully private floor-sitting spaces that require shoes to be taken off. A gradual transition from the relatively public standing spaces to the relatively private floor-sitting spaces can be observed.

In POOM, this integrative method is further enhanced by using split floors. As the first-floor embroidery workroom, the second-floor guestroom, and the terrace space – in contrast to the private residence spaces in the 1.5 and 2.5 floors – are all standing spaces that are open to visitors, these spaces are demarcated by the madang and staircase. These demarcations can also be understood as ‘boundaries’ that implicitly indicate how much of the house is open to the public, how long can one occupy that space, and the purpose of that space. But these boundaries can also be flexibly reconfigured at will to also present a visually unified space.

The experiment with floor-sitting and standing spaces sometimes functions to highlight the boundary between them, as in Sangsangrak where the workroom and guestroom as standing spaces are separated from the main building, or to showcase how they can also be bonded together as in the cases of Yeongchungjae and Chungudang where the two spaces appear to have seamlessly fused with one another. While this combination of floor-sitting and standing spaces will become a theme that will be requested in various ways in the future, the transition will not be easy. By utilising various meticulous combinations of floor-sitting and standing spaces, a0100z demonstrates new possible directions for housing design.

©Yoon Donggyu

Cheongudang. While the structure is western-style wood, it adopts depth and compartmentalisation reminiscent of traditional hanok. The façade uses wood carbonised by the family themselves from the house construction stage. ©Yoon Donggyu

Resurrection of Wooden Houses and Its Meaning

All a0100z’s houses are built using a wooden structure. Regardless of whether it uses a combination of heavy timber with lightweight timber structure or fully commits to a heavy timber structure, what is remarkable is that a0100z is trying to bring back the long-neglected wooden structure and use it in various ways. Aside from On Sill, where the heavy timber structure is fully exposed to allow its users to directly interact with the wood’s natural colours and texture, the heavy timber structures in the other houses are only partially exposed in large common spaces such as the living room, dining room, and kitchen to inform their users that this house has a wooden structure. One good example of this is Sangsangrak, where a thick wooden beam that runs across the two-storey high space that contains the living room, dining room, and kitchen has been left exposed. Resembling the beam that one can find in the main room of a hanok, the large amount of space surrounding the beam that might otherwise seem rather empty is imbued with a loose sense of division and stability without using any partitions.

There are also other interesting examples like Yeongchungjae and Chungudang which deliberately simulate the depth and compartmentalisation of a traditional hanok’s spatial composition despite the large roofs enabled by their lightweight timber structures. Like the architectural DNA that remains uncompromised throughout the tumultuous history of Korea, these houses – despite having western-style wooden structures – capture the feel of a traditional wooden hanok.

Wood is more than just structural material for a0100z’s houses. Wood is also actively used in the interior and exterior façades, and this has led the users to care for their houses. The family living in Chungudang used their own carbonised wood for the façade, and the families of Yeongchungjae and On Sill – after regularly maintaining their aging houses by adding fresh coats of paint over the columns and exposed wood – have developed a certain fondness fot their houses. Would they have experienced the same kind of joy that comes from caring for one’s home if they had lived in a concrete house instead? I think not. a0100z’s houses and their inhabitants’ attitudes remind us of the essence of home that we have long forgotten.

In these ways, a0100z’s houses challenge our conventional beliefs at every turn. And yet the reason why their attempts do not end up being too overt or forced is because Sung Sangwoo believes that a design for a house — which is an architecture that is closest to one’s life – can only begin after a deep reflection on the client’s life trajectory and direction. A young family with children, a middle-aged couple that lives with their sick mother-in-law, and an old couple whose children have all grown up and left—to understand these individually different lives, Sung reflects on the places that they have called and will call home in the past and future and draws out their answers. The bond of trust that is created over the time of questioning and answering manifests into distinctly unique designs.

a0100z’s hybrid experiments are still ongoing. But their direction will remain the same: that is, to preserve the real value of houses, to reinterpret what is familiar in an unfamiliar way, and to showcase a new possibility for houses towards which we should all aim.

Madangs of POOM (left) and Sangsangrak (right). Segmented madangs that are divided by differing ground levels were introduced. The madangs were divided into two or three segments, and each segment was designed differently with contrasting floor finishes and vegetation to demarcate their different purposes and acknowledge users. (left) ©Lee Hanul, (right) ©Yoon Donggyu

On Sill, a house that actively reinterprets the concept of madang. The onsill (greenhouse) placed in the centre feels like an interiorised madang, neither completely interior nor exterior space. The south madang, raised with a concrete cantilever structure, protects family privacy by blocking views from outside while creating cosiness by receiving views from inside the onsill. The north madang, which had its floor finished with stones and dirt, invites the green scenery of the nearby mountain into the interior.