SPACE October 2024 (No. 683)

Memorial Stone of Hoehyeon, 1000, Neighbor, Tree (2020) Image courtesy of a.co.lab architects

Memorial Stone of Hoehyeon, 1000, Neighbor, Tree (2020) Image courtesy of a.co.lab architects

The Confession of a Stone which Failed to Find Its Form

In a conversation in the SPACE No. 662 (Jan. 2023), Kim Jang Un (former director, Art Sonje Center) highlighted an episode concerning a review of public art designed by architects which approached public art as ‘a kind of project’. As soon as I read the article, I could tell that the young architects were us, and the project was Hoehyeon, 1000, Neighbor, Tree (2020) of the Seoul is a Museum. In his article, he was wondering why we were satisfied with a tattered project, quite apart from the original plan, due to the collection of different desires of residents, management agency, Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG), and Jung-gu Office. Ironically, we found his feedback comforting at the time. When we are invited to work on public art or pavilion projects, we work with quite a different approach to other architects. Usually, our society expects architects to create something that emphasises formal performances on a large scale, but we have taken a critical stand of this methodology in many aspects. Thus, we are sometimes invited to participate in fine art exhibitions as artists rather than architects. Kim’s criticism of ‘approaching public art as a kind of project’ is a welcome one considering our desire to avoid auteurism, but a rash judgment considering our willingness to work.

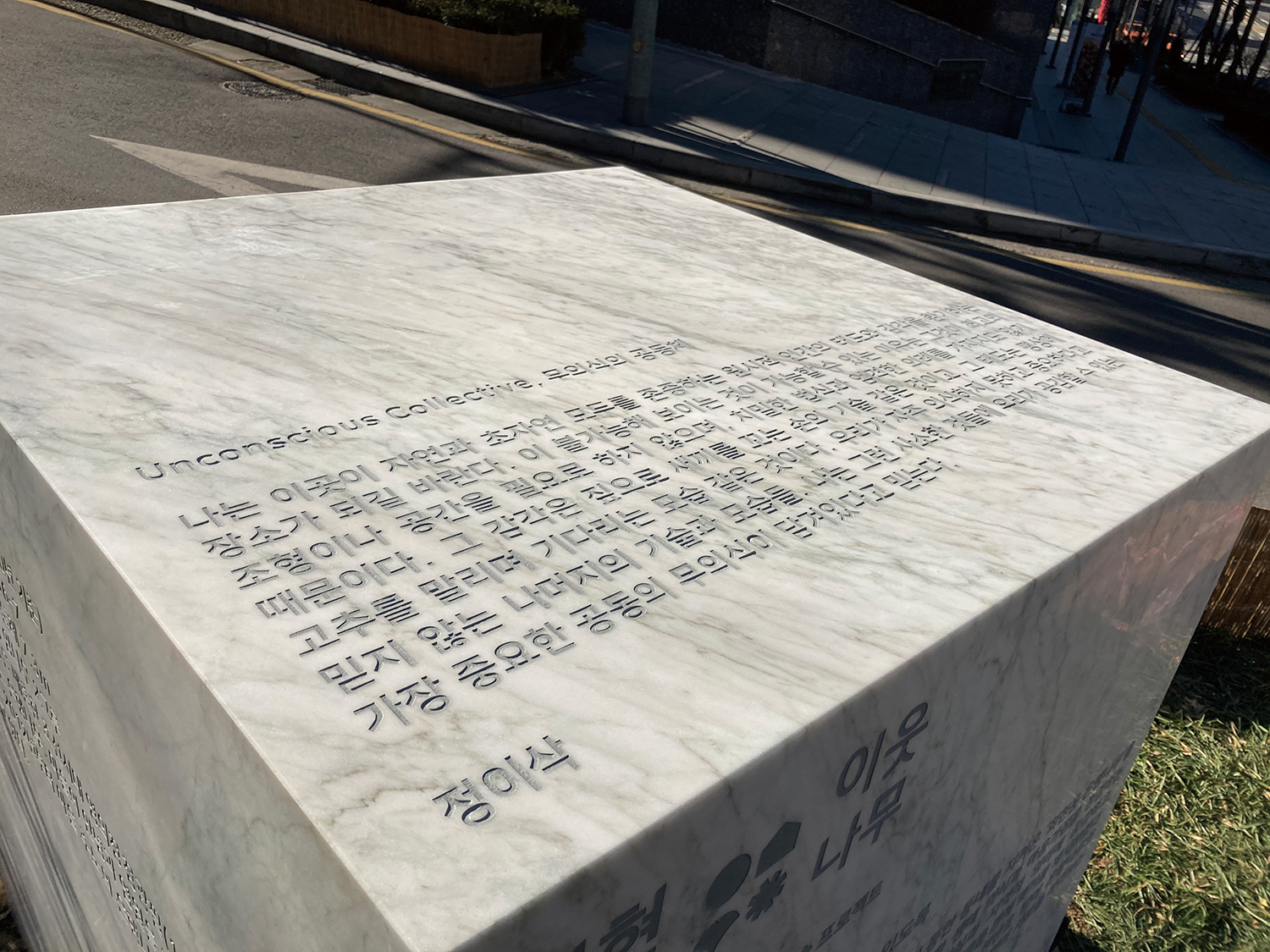

We don’t think we have to produce a lot of work to demonstrate sound ideas. It may be contradictory considering that the building industry is all about tearing down and building up, but this standard applies to all of our works. Hoehyeon, 1000, Neighbor, Tree still has a special meaning for me, along with my compassion for the interested party. The opportunity to create a permanent sculpture in the centre of Seoul would mean a great deal to many, but we believed from the beginning of the project that less is more when it comes to new things in our public spaces. Our submitted proposal was only text, and after we were appointed, we lacked the effort and ability to find the right form for what was outlined in this text. We could not escape from the compulsion to create something. On the contrary, as the project progressed, the selfishness of many primary agents and stakeholders lessened that burden. The chaotic situation of simply doing nothing was truly a wonderful outcome in the performance. The project management agency should fulfill the task of creating the memorial stone. We left some of the text from the proposal on the upper surface of the memorial stone, which is hardly intended for that purpose.

Unconscious Collective

I want this place to evoke a primitive human attitude and sense of respect for both the natural and the supernatural. The reason why this seemingly impossible thing is possible is that it does not require the best landscaping or space, nor does it have an elaborate form or strict rituals. The sense is like the manual skill of twisting a straw rope, and the attitude is like the waiting for chilli peppers to dry on a low wooden bench. The marginal skills and behaviours we don’t often notice and don’t consider important. I believe that these little things contain the most important collective unconscious with which we can sympathise.

‒ Text on Hoehyeon, 1000, Neighbor, Tree of memorial stone written by Chung Isak

Let It Be (2023) Image courtesy of a.co.lab architects

Fish Cart (2023)

©Hong Cheolki

Production and Reflection: Beyond Areum▼1, Continuity and a Natural Course

Nevertheless, I don’t consider doing nothing to be a virtue. We ask all why we keep practicing architecture. We do it even though we are reluctant to produce, because of the experiences in private production create ripples through our relationships with others. Socially, the oscillation of production and the relationships it creates are both a disaster and a miracle. If our world touches the evolutionary road in any direction, the tragedy of such catastrophes and the comedy of miracles are part of nature. When the tragicomedy process is over, both the tragic complaint and the comic touch will disappear, and they will be replaced by another hesitation, another private vibration.

At the same time as we produce, we also have to look back. There are many things we leave behind, and so we should pick them up. If we can, we want to fill in the overturned ground and the sinkholes left after pumping up water with the things we’ve left behind. Before we decide whether an object on the ground is new or banal, good or bad, we need solid and filled ground on which anything can stand. Our work is akin to filling in the holes in that ground, to solidifying it. It’s about cleaning up the places which growth and development have thrown away, and empathising with the urgent and clumsy products. This cleanup and empathy are the hope for continuity and natural course.

In the winter of 2020, I visited a sushi restaurant in Bukseong Port, Incheon. Once the largest port in the metropolitan area, it is now abandoned, its torn yellow fish stand nailed down with rusty nails. Influenced by this place, we presented Fish Cart (2023), a new fish stand in Bukseong Port, when we had the opportunity to exhibit at the Incheon Art Platform last year. On the new fish stand in the exhibition hall, we arranged the display with the site plan of the Sorae salt farm, the largest one in Korea, and the abandoned technical books of the Japanese engineers, along with props of fish models. After the exhibition, this new fish stall has been placed next to the existing ones in Bukseong Port.

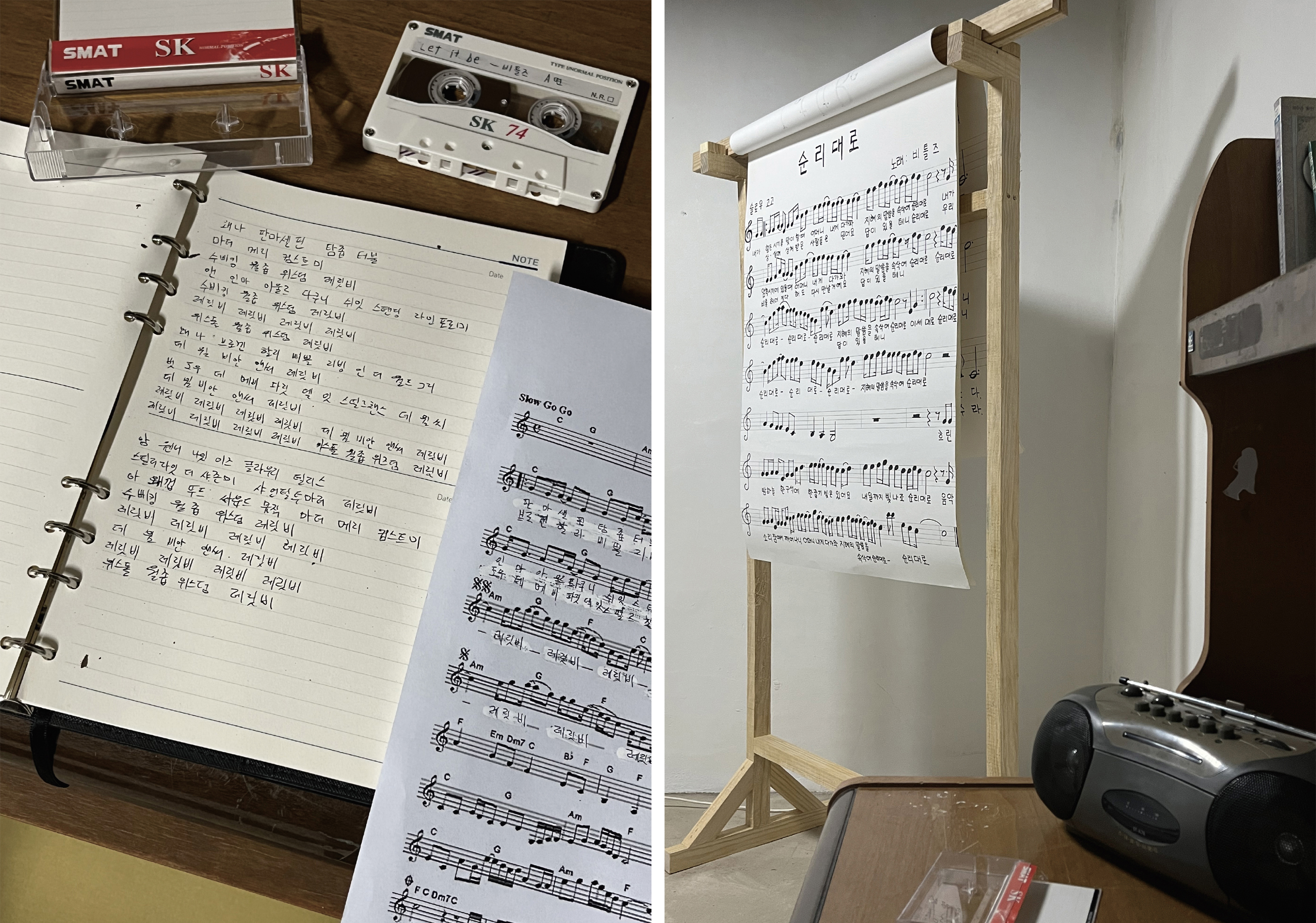

Last fall, we participated in a public art exhibition in the old town of Seongnam. Let It Be (2023) provided an opportunity to experience the room of Park Seongnam (then 14 years old), who was a student of Gwangju Seogwang Middle School (current Sungnam Seo Middle School) in October 1993. In the late 1960s, SMG relocated 120,000 people who lost their homes due to urban redevelopment to Gwangju-gun, Gyeonggi-do (current Sujeong-gu and Jungwon-gu in Seongnam). Seongnam was built on a nameless mountain hastily and haphazardly. The then 14 year old Park Seongnam recorded the Beatles’ Let It Be on the radio and sang along without knowing the meaning of the lyrics. Thirty years later, he understands the song’s meaning, but the natural course of Seongnam is still far-off. Today, Taepyeong-dong, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam-si is forging a redevelopment plan for the apartment complex.

The architecture of the Rest (covered in SPACE No. 634) pursues continuity and a natural course, but it is not sufficient. It has little attraction for the Rest and little power of its own. Therefore, it sometimes retains old values without interest or change. At the same time, the loss of momentum sometimes causes it to disappear recklessly. Its powerlessness is both hope and despair. The leaders ignore the Rest, weaving together relationships of singularity, like islets to create a plausible narrative. We must imagine a multi-stemmed narrative by discovering the stories of the Rest under the water. We also need to read history flat, even though it is jaggedly inclined. The Parthenon was originally colourfully painted, like the Korean five cardinal colours. You can’t ignore the colourful spirit while you praise a washed-out Parthenon. I propose ‘Beyond Areum’. Embracing the raggedy books and those who have white faith, toward the colourful and flat architecture.

Painter N’s House (2024)

Painter N’s House (2024)

Four Years, Three Practices

Painter N’s House (2024) in Yeonhui-dong is the remodeling of an old residence and studio that the client couple who are painters lived in for ten years. The project was an attempt to find a new form for their existing way of living. The first and second floors are accessed by the existing alleyway staircase as the original way instead of adding an indoor staircase, and the small but familiar scenery such as the existing cabinet inlaid with mother-of-pearl in the master bedroom and the IKEA ceiling manual lightings have been retained. The lush exterior insulation was stripped away to reveal the original decoration bricks, and we added similar bricks found from a redevelopment site over the mountain. Previous occupants have changed the building structure over the years. It was important to find a formal, three-dimensional grid within the existing house’s atypical floors and walls to complement the performance of the existing structure. Columns within the physical contact are reinforced with wood, beams by metal, and the extruded volume from inside the existing building finish rises to the level of the railing next door. The gutters have been left exposed to unite the ends of the roof, and downspouts have been placed on the structural axis or made as outdoor structural reinforcement. The hope was that furniture elements and minor devices would be part of the structure, organised to function as part of the whole system.

Be, Fore (2024) in Siheung is the rehabilitation of a neglected area in the sewage terminal treatment plant in Sihwa National Industrial Complex. We didn’t propose a program. Before we placed something here, we wanted it to be a backdrop to the various activities in the place. We created a minimal experiential device by finding out how the sewage terminal treatment plant works and the faded context of the existing site. Using the axes of the distribution and thickening basins, the centre of the inspection deck, and the pipes of the facility as guides, we intended to establish an open sequence of the individual underground civil structures. We wanted what we introduced to the space to be minimal tools that would guide light and water rather than the facilities. The abandoned industrial space and the primitive space for human occupation are complete opposites end of the spectrum but a very similar conception of form. While maintaining the existing shapes as much as possible, I tried to realise the unconscious community that is inherent in all of us through cheap contemporary materials and minimal architectural gestures into architectural forms.

Blue Hip (2022) in Galhyeon-dong is a new construction for a residence and workshop for a young artist couple. We had to secure the necessary interior space and a yard with privacy within a site where the usable area had been absolutely reduced due to the regulations for the road intersection and road widening. Our work is about finding order in a seemingly irregular world. Two calculable lines allowed for maximum occupancy within the given site. The two bands thus conceived provide a thin layer between the city and the house while maximising the building coverage. This urban liminal space provides an entry point for the dwelling on the second floor and a yard for the workspace on the first floor. The language of everyday architecture (semi-subterranean), which emphasises accessibility to the street, is partially applied. To minimise the height of the staircase to the second floor and maximise the ceiling height of the first floor, the indoor floor level of the first floor was lowered by 1m from the ground. Inside the first floor, a grid system was used to divide the space and determine the location and size of the windows, lighting, and furniture.

Be, Fore (2024)

Blue Hip (2022)

Blue Hip (2022)

1 perimeter of the rough circle formed by the two arms