SPACE October 2024 (No. 683)

From the 4th to 7th of September, Frieze Seoul was held at COEX in Seoul. Frieze, often mentioned alongside Art Basel as one of the world’s premier art fairs, first launched in London in 2003 and has since expanded to cities such as New York (2012), Los Angeles (2019), and Seoul (2022). Both its first and second occasions in Seoul received much attention. Frieze continues to capture the interest of various media outlets, from art magazines and lifestyle publications to the culture sections of major newspapers. With each edition, it’s becoming a large-scale urban event. Let’s take a closer look at how the term ‘frieze’ – deriving from classical architecture – is now making waves across Seoul’s art scene.

Installation view of SAC Gallery from Bangkok, Image courtesy of Frieze, Lets Studio / ©Lets Studio

Indian gallery DAG’s booth. Examining how each gallery divides the booth space is one of the interesting aspects of an art fair. Image courtesy of Frieze, Lets Studio / ©Lets Studio

A Look Inside the Convention Center

Art fairs and biennales are similar in that they both bring together some of the most noteworthy works of art from around the world under one roof. However, the same object can be seen from completely different perspectives depending on the setting. In a biennale, it becomes an artwork to be appreciated while in an art fair, it’s a product waiting to be sold. The fundamental distinction between art and product shapes the entire spatial experience of these two events. In an interview with Artforum, Matthew Slotover, co-founder of Frieze, explained that in a biennale, ‘there’s a certain relationship between things,’ while at an art fair, ‘you have 2,000 – 3,000 objects that were never intended to be shown together.’ In short, there’s little curation in an art fair. Instead, the visitors become the curators. By selecting and purchasing the items they want to own, they curate their own personal space. Even for those not intending to buy anything, visitors discover and connect with objects based on their interests and tastes, weaving their own new meaning from the objects on display.

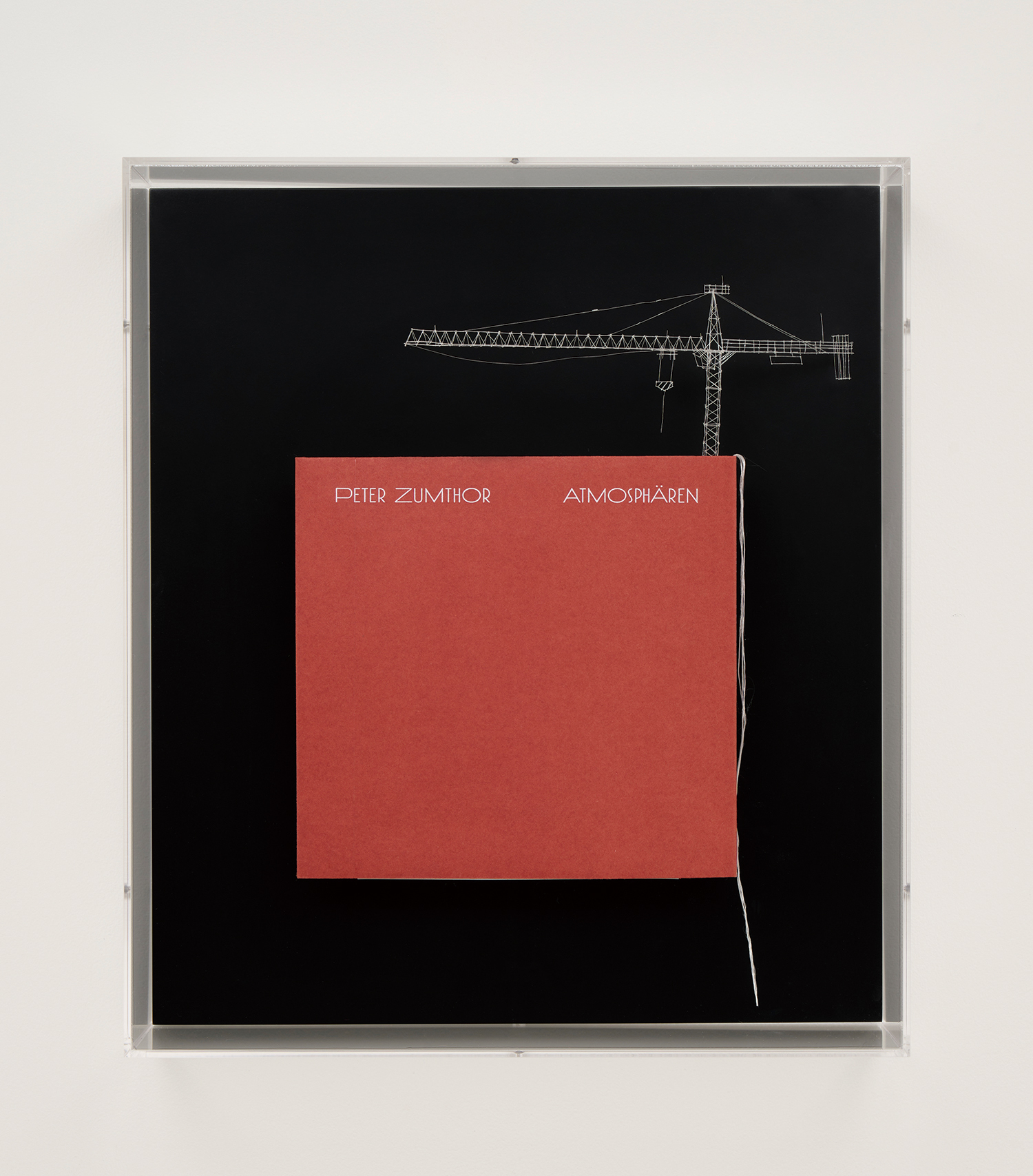

Takahiro Iwasaki, Tectonic Model (Peter Zumthor “Atmosphären”), 2024, book, 40.3×35.3×13.5cm, Image courtesy of ANOMALY / ©︎Takahiro Iwasaki

Anum, Phalaenopsis O, 2024, oil on linen, 50.5×75cm, Image courtesy of Yeo Workshop

Anomaly from Japan, which has participated in Frieze Seoul since its inaugural year, introduced the work of Iwasaki Takahiro for the first time. Though still relatively unknown in Korea, Iwasaki, born in Hiroshima, has long been fascinated by the construction and deconstruction of large structures, a theme influenced by his childhood growing up near the Atomic Bomb Dome. This fascination is uniquely reflected in the piece displayed at the booth, Tectonic Model: Peter Zumthor’s Atmospheres (2024). The work features a copy of Zumthor’s architectural classic encased in a clear acrylic box, with a small tower crane made of bookmark ribbons attached to the top of the book, turning this revered text into a kind of construction site. Is Atmospheres being dismantled for redevelopment, or is it being expanded?

Kosaku Kanechika’s gallery booth, Image courtesy of Frieze, Lets Studio / ©Lets Studio

Campus Valley at Ewha Women’s University, Image courtesy of EMAP

Meanwhile, the French gallery Jocelyn Wolff presented three gouache works by Isa Melsheimer, Nr 384, Nr 393, and Nr 398 (2015). Based on her profound understanding of architectural history, Melsheimer describes herself as an ‘archaeologist’ of forgotten or neglected buildings. She recreates familiar concrete structures yet remains silent about the origins of the buildings she references, sparking the viewer’s imagination. Some interpret this as portraying the landscape of a ‘post-human’ world through built environments devoid of human presence.

Isa Melsheimer, Nr 384, 2015, gouache on paper, 24×17cm, Image courtesy of Isa Melsheimer, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff

On the other hand, there are artists who create unique effects by omitting architectural structures. Singapore’s Yeo Workshop presented Anum’s Phalaenopsis O (2024), a diptych series that juxtaposes realistic still-life paintings with geometric form studies. To fully grasp this work, it is helpful to compare it with Anum’s other piece, Tea (2024). In Tea, which recreates the distinct Peranakan architectural style of Singapore, both representational and abstract elements coexist, but they are mediated by architectural structures. For instance, the walls and floor are filled with abstract patterns, while the man in the room is depicted realistically. In Anum’s recent diptych series, the architectural structure is removed, and the still-life and abstract patterns are placed in juxtaposition. Anum, who studied architecture in Malaysia before moving to Germany to become a painter, is noted by Charmaine Kok, associate of Yeo Workshop, for her avid reading of ancient Roman architectural texts.

Exhibition view of 'Dream Screen' at Leeum Museum, Image courtesy of Leeum / ©Kim Yeonjae

Another trend observed at Frieze Seoul 2024 is that of practicing architects becoming involved in how artworks are displayed, in that they aim to create ambiguity or optical illusions rather than establishing clear spatial order. The best examples of this are Suh Eulho’s OLED project and Kosaku Kanechika’s booth. Suh Eulho, who worked with his brother, artist Do Ho Suh, on a project dedicated to their father, artist Suh Seok, arranged the works in layers, allowing viewers to see from the entrance to the back of the exhibition space in one glance. This setup creates a space where the audience becomes immersed in the artwork. When visitors enter the ‘in-between space’ between the transparent fabric and transparent OLEDs, they appear like the moving figures often depicted in Suh Seok’s paintings. Kosaku Kanechika Gallery enlisted Ishida Kentaro (principal, KIAS) to design their booth in such a way that the ceramic works of Japanese artist Kuwata Takuro and American artist Dan McCarthy seemed as if they were created by the same hand. Ishida explained that he focused on the ‘technical similarities’ between the two artists, especially in their glazing techniques. Typically, marketing and sales strategies magnify small differences to emphasise a product’s uniqueness. However, Ishida’s design took a different approach, downplaying and blurring the distinctions between the two artists, effectively erasing those subtle contrasts.

Exhibition view of Suh Eulho and Do Ho Suh's OLED project, Image courtesy of LG Electronics

The View Outside

Before and after the four-day Frieze Seoul, the city’s art scene takes on a slightly different appearance. Yoon Wonhwa, a visual culture researcher, offered a keen observation of the changes that occur in Seoul during Frieze week: ‘Almost every event that takes place during the first week of September is planned with Frieze in mind, so there’s no avoiding it. [...] The flow of people changes, and the mood and impression of entire neighbourhoods shift. It felt as though the very sense of place was temporarily altered. Of course, when the event ends, that atmosphere disappears.’ The degree and manner in which this ‘sense of place’ alters impressions of the city depend largely on the unique spatial characteristics of each exhibition space. A prime example is the Leeum Museum of Art, which transformed its underground exhibition space into a massive mansion. Rirkrit Tiravanija, the artistic director of the 2024 Art Spectrum group exhibition ‘Dream Screen’, turned the museum’s ground gallery into a space with over 20 rooms, courtyards, entrances, and hallways. Tiravanija was inspired by the Winchester House, a labyrinthine mansion built by the Winchester family, who made their fortune in firearms, to ward off the spirits of those killed by their weapons. Leeum Museum of Art explained that the complex layout reflects contemporary feelings of disorientation and isolation. The more people filled the space, the more its mystery and claustrophobia intensified. When I later encountered the same faces in the long line outside Pace Gallery or in a small gallery on Gyeongnidan-gil, it felt as if Itaewon itself had become a vast labyrinth for those who had lost their way, reflecting the maze-like spaces inside the museum.

A visitor at Frieze Seoul 2024 inspects a painting, Image courtesy of Frieze, Lets Studio / ©Lets Studio

Until last year, Frieze Week was primarily focused on Hannam, Samcheong, and Cheongdam. This year, Euljiro has been added to the list. The special edition of the art monthly The Art Newspaper introduced Euljiro as an exhibition area with an ‘alternative identity’, noting that these spaces are ‘located in unexpected places, making them hard to find even for locals’. Euljiro’s alleys are intricately intertwined, and many of the exhibition spaces are tucked away on the tops of buildings or hidden in obscure corners. However, during Eulji Night (2 September), when exhibition spaces in Euljiro stayed open late for Frieze, things were different. Simply following the crowd as people chatted about art led directly to the galleries. In this way, the ‘flow of people’ created a stronger connection between the exhibition spaces in Euljiro. The largest exhibition space in the area, artspaceHYEONG filled its five-storey building with works by Korean artists. As one curator described it, moving between floors felt like getting a glimpse of the ‘unique cross-section of Korean art’.

One of the new developments during Frieze Week this year was the involvement of universities. Ewha Womans University College of Fine Arts collaborated with Frieze to host the exhibition ‘All Things Weaving the Universe, and Their Quantum Relationships’. The Frieze Film Program, which was previously held in independent and non-profit art spaces in Tongui-dong, Anguk-dong, and Insa-dong, moved to a university campus this year. They scattered 15 screens across the campus, showcasing works by both artists and students. The ‘outdoor theater role’ of the campus valley, as mentioned by the architect of the Ewha Campus Complex, Dominique Perrault, (covered in SPACE No. 487), was thus extended throughout the campus. However, had the programme more actively explored the potential of knowledge production alongside the activation of campus spaces, it could have been even richer. For example, the Art Basel Visiting School programme, run by the AA School of Architecture in collaboration with the University of Basel Graduate School of Social Sciences, provides a strong model of what universities can uniquely offer. Their aim is less about tours and more akin to anthropological fieldwork, where students, under the guidance of instructors from architecture, curating, and social sciences, critically analyse Art Basel, one of the most important art fairs in the contemporary art world. For instance, they explore how Art Basel might integrate more ‘thoughtfully and sensitively’ into the existing urban fabric, rather than remaining a ‘city within a city’.

Exhibition view of Artspace Hyeong, 3rd floor, Image courtesy of artspaceHYEONG / ©Xunguuk Jang

In the Artforum interview mentioned earlier, Slotover explained that Frieze aims to be more of a ‘festival’ than a ‘trade fair’. This is why Frieze London, the original Frieze fair, is not held in a typical MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions) venue like Frieze Seoul. Instead, each year, Frieze London collaborates with architects to build temporary structures for the art fair in Regent’s Park, a green public space in London. In the 2000s, architects such as David Adjaye, Jamie Fobert, and Caruso St John designed these structures, while in the 2010s, the likes of Carmody Groarke, Barber Osgerby, Annabelle Selldorf, and, this year A Studio Between took on the task of designing the tented pavilion. Of course, simply collaborating with architects doesn’t automatically remove the ‘trade fair’ framework, nor does it guarantee a ‘festival’ atmosphere. However, Frieze London offers a freshness that cannot be experienced in conventional spaces like COEX, which stays true to the traditional convention centre model. During Frieze week, various art spaces in Seoul used their unique spatial assets to alter the ‘mood’ of their neighbourhoods and welcomed visitors who were eager to experience the festival vibe. Could the festive energy displayed by Frieze Seoul’s side programmes one day draw the fair out beyond the walls of the convention centre?

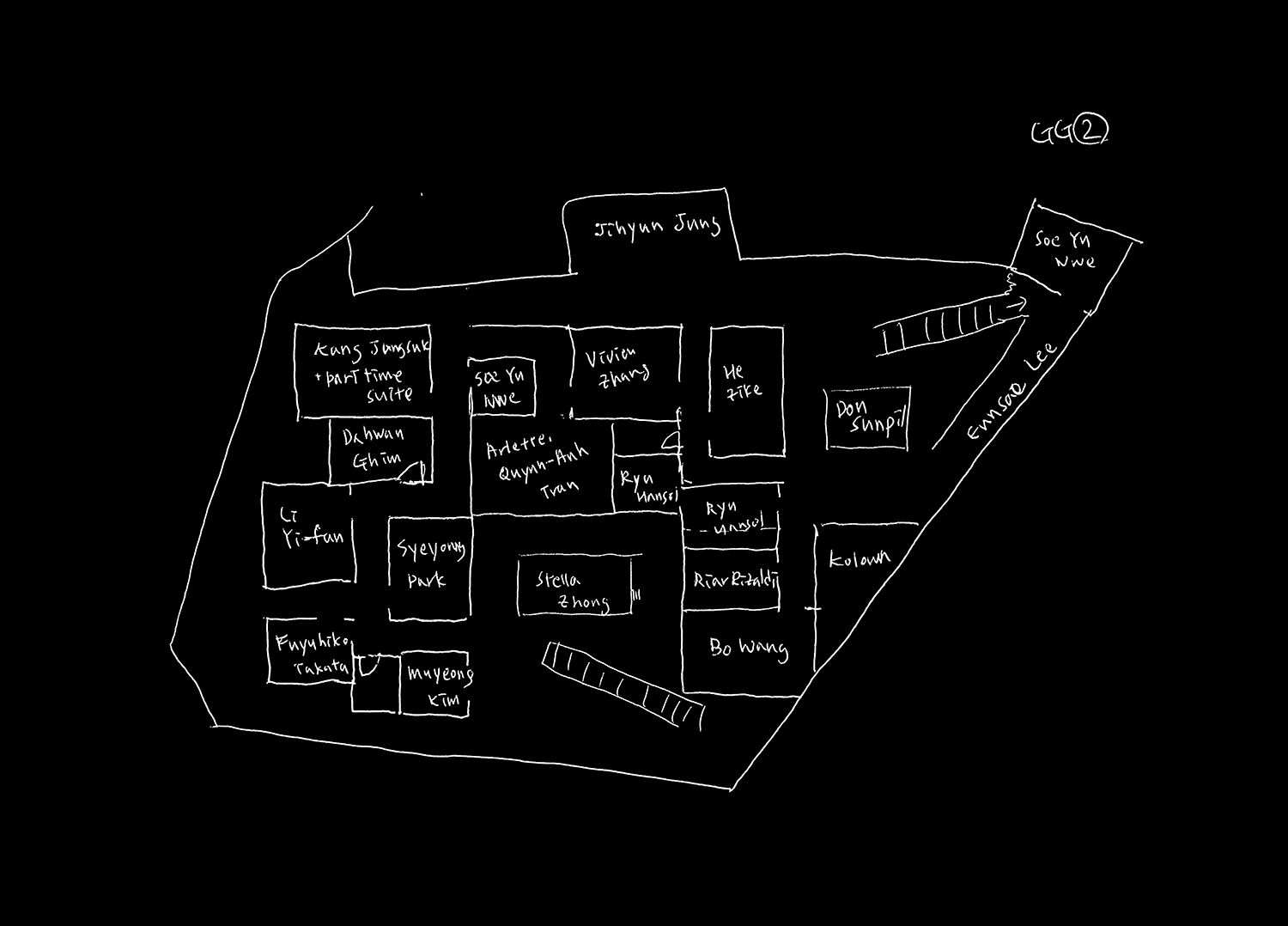

A hand-drawn floorplan for 'Dream Screen' at Leeum Museum of Art, Image courtesy of Leeum