SPACE September 2024 (No. 682)

Where can we locate an alternative way of living life in our society? Phenomena like ‘apartment republics’ and ‘apartment kids’ have become pervasive and no longer a novel social phenomena in Korea. The exhibition ‘Performative Home: Architecture for Alternative Living’, which opened at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Gwacheon in July, challenges the familiar urban landscape and suggests that other forms of dwelling are not just possible but promising. The 58 houses, excluding those built in detached housing developments in new towns and luxury homes with a floor area of more than 100 pyeong (330m2), are a counter-declaration to the apartment republic and act as an archive for an alternative way of life that is not far away. Meanwhile, the exhibition ‘Investigating the Archetypal Korean Apartment Layout’, scheduled for the 28th of September at Gwangwoon interior, intends to discover the possibility for an alternative everyday life by examining apartment floor plans that are so familiar that they have not been discussed in depth.

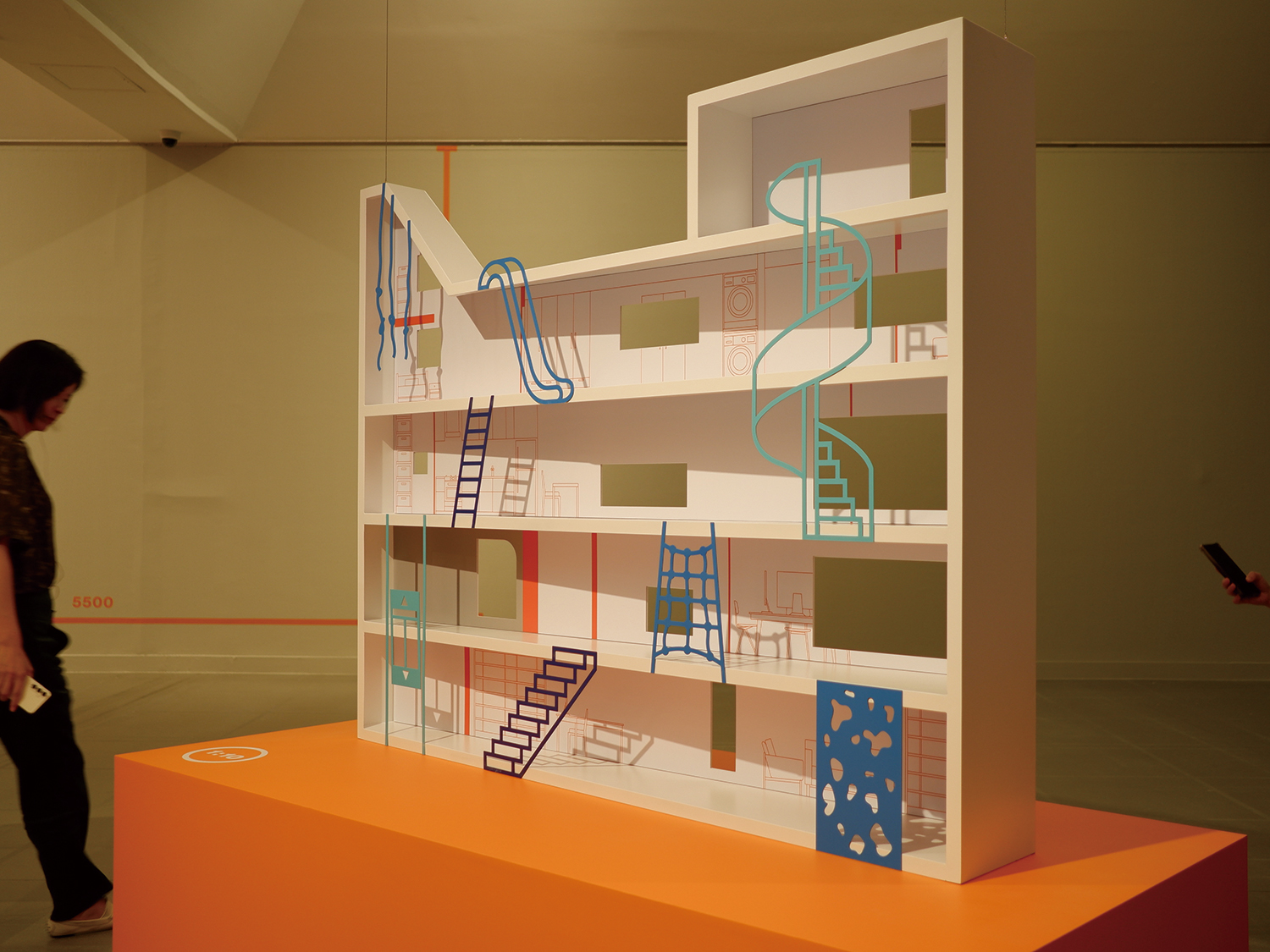

Exhibition view of ‘Performative Home: Architecture for Alternative Living’ ©Son Mihyun

The Ideal and the Reality of Korean Housing: Detached Houses and Apartments

‘Daunting, overwhelming, pie in the sky, a baby in the woods, extreme challenges, a great deal of trouble….’ These are all modifiers that come with building a house. The decision to build or renovate one’s home in Korea is neither assumed nor easy. In our society, where homes are seen as more of an investment than a place to live, detached houses are more challenging to resell than the typical apartment, making them less valuable than apartments of the same size. This is one of the main reasons why it’s hard to opt for a detached house. According to the Statistics Korea’s Housing Census in 2023, 19.8% of all houses in Korea are detached houses. While these detached houses legally include multi-family dwellings and mixed-use housing (such as commercial properties), only 13.4% of detached houses are occupied by only one household.

On the other hand, apartments are the dominant form of housing in Korea, with more than 300,000 built annually. Branded apartments mass-produced by big construction companies from the 2000s have accelerated the standardisation of floor plans, making them a convenient form of living and an excellent asset.

Basecamp Mountain (2004) by studio_K_works (principal, Kim Kwangsoo) ©Kim Jongoh

‘Performative Home: Architecture for Alternative Living’

Even in the Korean situation described above, some people wanted to build their own ‘house’ rather than live in an apartment. Curated by Chung Dahyoung (curator, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art), art director for the 2025 Venice Biennale Korean Pavilion, ‘Performative Home: Architecture for Alternative Living’ introduces residential architecture that goes beyond a well-planned apartment for a family of four, and explores the architectural stories of people who have been ahead of the curve in pursuing alternative ways of living.

The exhibition presents a total of 58 residential works designed by 50 architects (teams), from emerging to established, divided into six sections. What alternatives do we discover in each of the six sections—‘The Home as Architectural Manifesto’, ‘Reimagining Family Homes’, ‘The Home as a Social Ground’, ‘The Home as a Panorama’, ‘Small Homes, Renovated Homes’, ‘The Home as a Temporary Dwelling’?

The Home as Architectural Manifesto

‘The Home as Architectural Manifesto’ is a collection of the architect’s various experiments and architectural declarations. Among them, Basecamp Mountain (2004) by studio_K_works (principal, Kim Kwangsoo) is a unique house and café that combines a plastic house and a container house. Most of the projects’ clients in this section are the architects, and the projects feature experiments that the architects could perform because it was their project. On the other hand, the experiment at Basecamp Mountain was born out of the owners’ extraordinary lives. Based on the philosophy that ‘a home is a place to stay, eat, rest and go out for a while on the long road of life’, the couple commissioned a house for living, not settling, in the city.

Although both the owners and Kim thought this temporary construction would last five to seven years, Basecamp Mountain is still going strong 20 years later. It’s a reminder that the 30-year lifespan of an apartment is not natural, but a social one, driven by the pressure to rebuild.

(left) Model of Beyond the Screen (2019) by OBBA, (right) Model of House M (2018) by o.heje architecture

Reimagining Family Homes

A day before the exhibition opened, the Supreme Court of Korean ruled in favour of same-sex spouses qualifying as dependents for health insurance. In addition, the country’s total fertility rate reached a record low of 0.72 in 2023, marking the beginning of a new era in low birth rates. As such, our society is being forced to embrace more diverse lifestyles beyond the traditional heterosexual family of four. ‘Reimagining Family Homes’ reflects this social trend, featuring homes with pets or plants, large families, two couples without children, and single young adults. What would a home look like if it was not a standardised apartment plan for a family of four but an architect-designed home for different kinds of families?

Unlike apartments and multi-unit dwellings, which are often designed for human occupancy where furniture is often used to create a space for pets, these homes are designed from the ground up for families with pets and can accommodate pets at the architectural scale.

One such example, the GoGaeJip (2016, covered in SPACE No. 587) by Lifethings (principal, Yang Soo-in), is a house for a family of two people, two cats, and two dogs. The family has lived in the house for over eight years, and three of their pets have crossed the rainbow bridge. It shows that living with animals as part of a family requires both spatial and temporal considerations, as their lives are shorter than ours. The owner couple said they wanted the house to be remembered as ‘the home where three friends lived happily for eight years’.

Other examples, mostly built since the late 2010s, include a house with three generations and 11 families (Yeonhui Living Workshop, 2018), a home with separate spaces for husband and wife (Malefemale House, 2018, covered in SPACE No. 625), and co-living for young single households. (Mangrove Sungin, 2020) Still, it was disappointing that there were no examples of houses inhabited by queer couples, non-married members of the communities who are actively redefining the meaning of family.

1:2 scale model of Basecamp Mountain in Gallery 1

The Home as a Social Ground

The previous section examined architecture for alternative living within the family framework, while ‘The Home as a Social Ground’ focuses on living with neighbours.

These include those that are meant for one family but open up space for neighbours to stay and interact; multi-family and multi-generational homes where multiple families live together voluntarily; co-operative homes that bring individuals together to continue the practice of building their own homes; and dormitories for young people living on their own.

In particular, the story of two or more close family members building and living in houses nearby together is something we all dreamed of as children. But while we dream of a more active relationship with our neighbours, rather than a passive relationship from within an apartment where it’s best to stay out of harm’s way, it’s not always easy to make the decision to take action. As you can see, all of the cases of unrelated families living next door or together are led by an architecture professor or an architect himself.

Nevertheless, there are also some examples that show that living in active relationships does not have to be difficult. One such example is Beyond the Screen (2019), a flat-style multi-family housing by OBBA (co-principals, Kwak Sangjoon, Lee Sojung). Typically, flat owners are keen to maximise the private area for rental, so it’s not easy to try something new. Beyond the Screen utilises a skip-floor structure to maximise the private area, while the exterior walls surrounding the core of the building are hollowed out and stacked with bricks to create a kind of courtyard that faces the outside world. Someone puts out a plant pot, someone hangs a Christmas wreath, and the courtyard is gradually enriched. Perhaps these small attempts can help us become neighbours instead of strangers next door?

The Home as a Panorama

‘The Home as a Panorama’ explores how house building in the countryside has changed. Among them, we can find the recent trend of building rural houses in House M (2018) by o.heje architecture (co-principals, Lee Haedeun, Choi Jaepil). Three generations of the owner’s family share the house at one time. It's a way of living in the countryside more actively than the so-called ‘4 do 3 chon’ (four days in a city, three days in the country). Indeed, while there have been fewer and fewer households are settling down in the countryside, the ‘4 do 3 chon’ life style, which provides both the convenience of the city and the atmosphere of the countryside, is gaining popularity. House M consists of The Side House, The Main House, and The Small House. In The Side House, the owner’s parents and other family members reside, having come to help during the harvest season to tend the crops, consume them together, and prepare for next year’s production. The Main House is the space that best reflects the ever-changing nature of the people who live in it. It is a kind of family meeting place that can accommodate the owner’s parents when they are in town during the busy farming season, the owner and his wife who spend a third of the year travelling abroad for when they are preparing for or returning from a trip, and the children when they visit during school holidays. The Small House is an attic above The Side House and The Main House, where one can relax and take in the countryside.

1:10 scale section model of House THIN-THIN (2018) by AnLstudio in Gallery 1

The signboard used in Eemizip (2023), by Mundo e hoje (principal, Yim Taebyoung)

Small Homes, Renovated Homes

‘Small Homes, Renovated Homes’ collects stories of people living on unique small plots or fixing up old houses in urban centres where land is scarce. Those who continue this practice of house building see the house not as real estate but as a place where they will continue to live, which inevitably leads them to consider the sustainability of their lives and cities and to adopt an attitude of downsizing. 50m2 House (2015) by OBBA is located at the entrance to Gaemimaeul in Hongje-dong, one of Seoul’s disappearing poor hillside villages. The owner, a newlywed, needed to find the right plot of land to build a house within his budget. The owners decided to build the house not because they ‘wanted a bigger house, so they kept moving to a bigger house’ but because they wanted to live a simpler life. The 1 pyeong (3.3m2) of exterior space is often used as a vegetable garden, sometimes as a playground for children, and, unlike apartment buildings, detached houses are less sensitive to noise. They can be used as a community space where the owners can hold a ‘backyard spring greeting’ or ‘house film festival’.

House THIN-THIN (2018, covered in SPACE No. 613) by AnLstudio (co-principal, Ahn Keehyun, Shin Minjae) is a house built on a narrow piece of land that the Gyeongbu Expressway cut off to create a buffer green space. The unfavourable conditions of the 2.5m border width led to the unexpected possibility of a parking lot exception. Also, the buffer greenery located right next to the house becomes the yard of the house. This example turns the assumption that single-family homes must have a yard on its head and makes us consider how life in dense urban centres should be.

The Home as a Temporary Dwelling

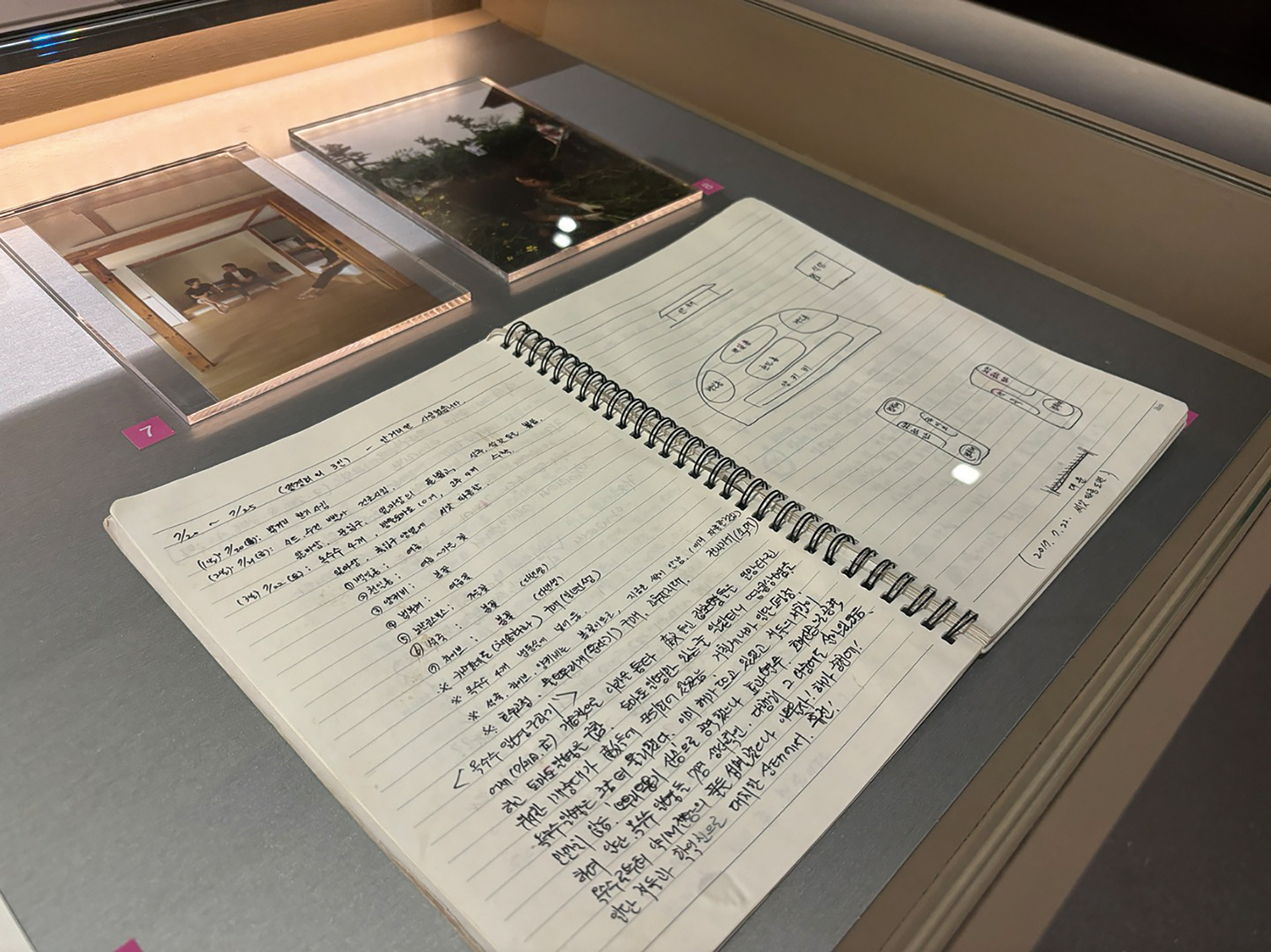

‘The Home as a Temporary Dwelling’ puts together a collection of weekend homes and stays where the accommodation itself is the purpose, centred around unusual or nondaily architectural spaces. Here again, we find a house shared by the hour. Unlike House M, which is shared by a family of three generations, the Gosan-jip (2017) is by a root architecture (co-principals, Lee Changkyu, Kang Jungyoon) shared by eleven families. They retain the dwelling format of a traditional Jeju Island house but have modified it to accommodate modern life. Angeori (central structure) became a space for families, bakgeori (subordinate structure) became a single room for a single person, and soemak (stable) became a shared kitchen where families could meet when they visited the main and the subordinate buildings.

The shared villa was initiated by Kang Miseon (professor, Ewha Women’s University). Shared houses, co-living and co-working spaces, and other ways of sharing space are rising, but a villa shared by eleven families still seems reckless. But they’ve been sharing their villa for the past seven years without incident, with agreements in place for things like ownership changes and several rules to make operate the villa easier. Kang has a very positive opinion of shared cottages, noting, ‘The maintenance and financial burden is shared by eleven people, but the joy of having a villa is the same.’ The records of the Gosan-jip on display shows that, one family shared their experiences of weeding and sowing flowers, another of fixing electrical equipment, and the another of being bitten by and catching centipedes. These Gosan-jip show us what life can be like when we let go of ownership attachments based on the expectation of rising home prices and prioritise the value we get from using a space.

The records of Gosan-jip (2017) by a root architecture

‘Investigating the Archetypal Korean Apartment Layout’

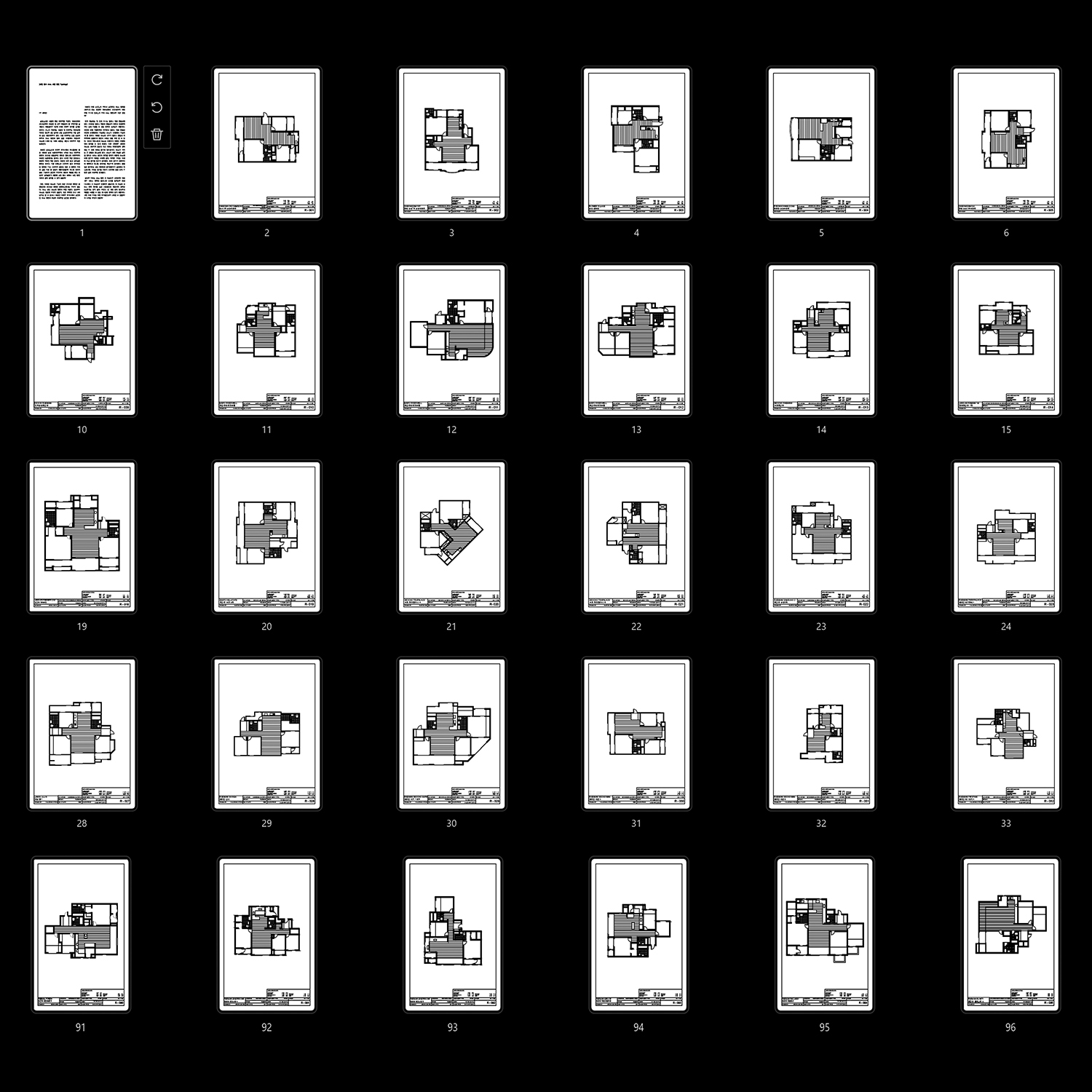

Meanwhile, an exhibition, ‘Investigating the Archetypal Korean Apartment Layout’, which reveals the results of the namesake workshop conducted by Ko Jaehyub (adjunct professor, Hongik University) and Chon Jaewoo (principal, HYPERSPANDREL), aims to discover new possibilities for an alternative way of life by targeting the most common type of housing: the apartment, which is the opposite of a detached house. The intention is that we need to understand the existing rules before we can propose ‘alternatives’. Kukminpyeongsu (standard area), that the exhibition focuses on, refers to apartment units of 33 pyeong (108.9m2) with less than 85m2 dedicated floor space, considered the most common and standard size for a family of four. It is also typically the size of the first home most people buy.

Although the size is now so familiar that it is no longer new, Ko and Chon wanted to analyse new questions with the objective eye of an architect. Are standard-sized apartment floor plans changing with the times, or are we still living in the same floor plans created decades ago?

With more than 80 participants, they collected and drew floor plans for 1,000 33-pyeong-type branded apartments built since the 1990s from the top eight builders in the 2023 contractor rankings.

While there were some familiar trends, the results were more varied and interesting than expected. In 2006, living room modifications were legalised, allowing balconies to be extended. The desire to own even one more pyeong of space in a densely populated metropolis has led to the transformation of 33-pyeong-type flats from two-bay to three-bay to four-bay, and finally creating corridors inside the units. Improvements in home appliance technology, such as washing machines, dryers and air conditioners, have reduced the role of balconies, making balcony extensions a necessity rather than a choice. At the same time, the living room and master bedroom, where guests were typically welcomed, have become smaller, and the space for the children has increased. On the other hand, new forms of standard area were also being experimented with in new cities. Even within these uniform apartment plans, there were many attempts to do something different.

Imagining Realistic Alternative Forms of Housing

‘Performative Home: Architecture for Alternative Living’ brings the seemingly remote and unrealistic object of the detached house into the realm of the more intimate space and shows that life outside the apartment does not have to be highly complex. To achieve this, the exihibition shows the building as occupied and people living in it rather than as a brand-new building just after completion, as is often the case in architectural media. Each section shows a film compiled from photos and videos taken by the residents of the houses. Actual plaques, cleaning logs, and guest books were displayed alongside models and drawings of each house. The caricature models created for the exhibition by Various Artists and Architects … (principal, Lee Yoonseok) are one way in which the architectural work has been designed to be accessible to the public. It shows the house not as an architect’s work of architecture but as a fully realised ‘home’ in every sense and makes the viewer wonder if they could live like this. At the same time, the gallery functions as a kind of architect’s showroom, open to the desires and interests of visitors. Visitors often discuss which architect they would choose if they were to build a house or which architect’s work suits their style. This line is further developed by the 58 books at the end of the exhibition, which collects all the books on house building and materials from the 58 houses. However, it is tough for an individual to implement the practices of these homes, a collection of unique examples. It is meant for alternative living and is unlikely to become a universal form of housing. On the other hand, the analysis of the apartment floor plan in ‘Investigating the Archetypal Korean Apartment Layout’ is more universal and realistic, even if it has not yet presented alternative possibilities of concrete everyday life. Somewhere between the two exhibitions, we hope to find the key to a better future form for housing.

Part of the apartment floor plan analysed in the ‘Investigating the Archetypal Korean Apartment Layout’ workshop ©Ko Jaehyub