SPACE September 2024 (No. 682)

Trocadero Plaza, overlooking the Eiffel Tower, became host to the Champion’s Park, as a celebration ground for medalists and the public. ©Clement Dorval, Ville de Paris

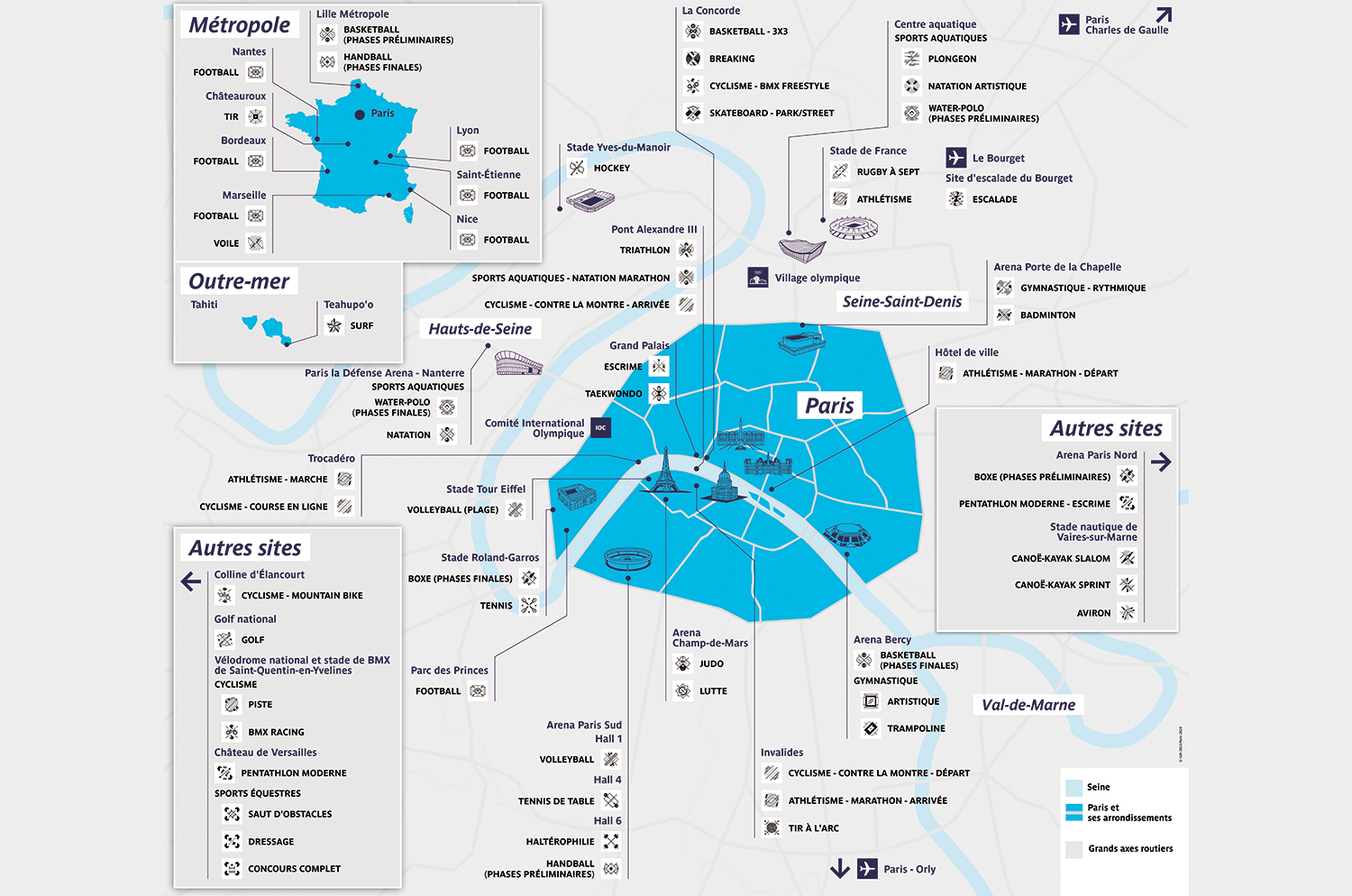

This summer, the Olympic Games made its return to Paris for the first time in a century. Launched with an opening ceremony on the Seine River, with fierce competitions playing out in landmark sites such as at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, in the Versailles Palace, Concorde Plaza. If hosting mega sporting events has achieved notoriety as a means of securing the political and financial backing necessary for urban redevelopment, the Paris 2024 Olympics took on the motif of urban regeneration with its relatively modest budget of approximately 9 billion EUR. The Paris City has pointedly set forth a ‘de-growth’ urban regeneration model, placing emphasis on renewing living environments for Parisians as opposed to national or urban marketing. By drastically reducing the number of newly built stadiums, a concerted effort was made for projects such as swimming in the Seine River and installing bike lanes in the city centre – all which are more are less in line with the last decade of urban planning in Paris. The question remains – can such a strategy succeed in providing a new foundation for a future Paris, well after the Olympics are over?

Keeping their pledge to use 95% existing or temporary venues, the games were held in renovated or repurposed venues in the heart of Paris. ©Paris 2024

Mega Sporting Events and the City

At the inception of the first French Republic, shortly after the French Revolution, the mathematician Charles-Gilbert Romme created the Republican Calendar, entirely free from religious or royalist impact. This calendar, composed of 12 months of 30 days each, had an additional 5 – 6 days at the end of the year. Romme primarily proposed that the leap year, falling once every four years, be called the ‘year of the Olympiad’, and that the remaining day be used to hold a sports competition. At the time, the public security advisor for Paris proposed that these games be opened on the Champs de Mars Plaza, and in 1796, tens of thousands of spectators gathered to watch the likes of wrestling and long-distance running competitions. While the Republican Calendar, and this form of the Olympiad, was suspended under the reign of Napoleon, it would later serve as an inspiration for the modern form of the Olympics, created in 1896 by the Pierre de Coubertin.

The Olympics as we know them today seem to at a far remove from Coubertin’s Olympics, hosted on the Champs de Mars Plaza and all over the city, as inspired by the spirit of the French Revolution and the Paris Commune. The games today, attracting fans worldwide and operating under strictly controlled broadcasting licenses are defined as a ‘mega sporting event’, with municipalities fervently chasing this ‘golden ticket’ that could secure a massive cash injection for urban development. Evidently, past Olympics have been successful at providing a fresh look for cities like Barcelona or Athens, by redeveloping post-industrial brownfields, and therefore opening up dense and closed of cities to the sea. However, these sporting events have also been criticised for fueling capitalistic logic, and hence inciting urban displacement or gentrification or producing ‘white elephants’, whether it be in the context of emerging economies like Rio or Beijing, or global financial centres that have vowed to invest in social inclusion like London or Tokyo.

Paris has the highest population density among European capitals. The temporarily built venues are nestled tightly into the urban fabric.

The Paris City and Its Urban Strategy

This summer, under the theme of Games Wide Open, Paris achieved its goal of hosting the Olympics for a third time, coming second to London. Following the Paris Olympics just after the Worldwide Expo (1900) and after the First World War (1924), the Paris 2024 Olympics herald a return to the city after a century-long absence. After three failed bids since the 1990s, in 2017, the Paris City made the ultimate decision to reframe the games as environmentally conscious and low cost. It proposed that 95% of its stadiums be reused or temporary fixtures, contributing to both reduced construction costs and lower pollution rates. As a result, the only new construction projects to count are a sports arena, as well as an Olympics village and swimming arena in the relatively impoverished northern suburbs.

This agenda set by the municipality falls largely in line with the climate-friendly political agenda of the long-time mayor Anne Hidalgo, and Carlos Moreno’s ‘15-minute city’. To put it in the words of an urban planner for the city, ‘all urban planning decisions are made by first determining their ability to tackle climate change.’ The mayor had already pledged the ambitious, and somewhat unrealistic, goal of reducing carbon emissions by 80% by 2050 upon election in 2014. And today, the municipality claims that the past decade has seen the accomplishment of a 35% reduction in car traffic (50% reduction over 20 years), a 25% reduction in micro dust particles, and a 40% reduction in nitrogen dioxide.

Yet, in spite of this, Paris remains resolute in continuing to prepare itself for hot summers, of potential temperatures rising above 50 degrees. (India, at the same latitude, already reached 51 degrees in 2022.) Since last hosting the Olympics a century ago, average Paris’ temperatures have risen 3 degrees, with the likelihood of experiencing abnormal temperatures over 30 degrees has increased three-fold. Moreover, greenhouse gas emissions, a true marker of climate change, have also risen up to 30% over the last decade. Like an enormous beast unfurling in fantastical metamorphosis, Paris, and its immense antiquarium, must figure out how to combat climate change, exemplified by the partial use of UV-resistant or double-glazed windows as part of the restoration of the Grand Palais.

The Champs-Élysées Street. Having completed open water swimming in the Seine River, triathletes complete their competition with cycling and running through the major north-south and east-west axes of Paris.

Out with the Cars, In with the Bikes

Rivoli Street: a 3km long boulevard that forms the central east-west axe of Paris, starting from the Concorde Plaza and cradling the Louvre Museum and the Tuileries Garden on one side, as 53 vein-like roads branch out to the left and right banks of the city. Since the 2000s, the once-thriving commercial industries housed under the repeating neo-classical arcades have shifted towards lacklustre souvenir shops and five-star hotels, with up to 25,000 vehicles passing by each day resulting in raucous traffic jams.

Since the Coronavirus Disease-19 crisis, the situation on the Rivoli Street has changed, to say the least. The road, once dominated by car traffic, has taken on a livelier tone, where cyclists, commuters and tourists abound. Since initial installation of bike lanes in 2017, the Coronavirus Disease-19 restrictions helped the Paris City permanently establish ‘corona-pistes’ – bicycle lanes – while gradually ramping up restrictions on traffic. Today, up to 94,000 cyclists pass through the Rivoli Street each day, with only a few select vehicles allowed to circulate on the two remaining traffic lanes, at a meagre 30km per hour. During the games, the Rivoli Street was central to an immense security zone—car traffic was more or less banned, with over 15 million visitors and members of the press moving from venue to venue uniquely on foot, bike or public transport.

While Paris is a relative latecomer to cycling infrastructure planning, compared to London or Utrecht of the Netherlands, it is rapidly making results. If a mere 440km of bike lanes existed in 2010, this has now increased to 1,300km inner-city, with an immense sprawling 4,000km network reaching deep into Paris’ suburbs. The city claims that such a commitment to reducing car traffic has paid off, with air pollution decreasing by 40%. Paris’ urban design is increasingly geared towards discouraging drivers, with parking fees for SUVs tripled, over 50,000 parking spaces eliminated, over 100 car roads closed down, and an upcoming full ban of diesel cars by 2025.

Nevertheless, as one urban planner suggests, putting bike travel first has resulted in the formation of a new ‘hierarchy of the street’. As bikes takeover the streets, situations arise where pedestrians feel unsafe crossing the road. Yet, he claims that it’s up to bikes to stop, as a signal that the problem is ‘cars, not bikes’. The fact of the matter is that a rare opportunity has arisen, whereby it may be possible to redefine who should be at top priority on the street. As part of the scheme, cars are being banned from passing in front of nursery or elementary schools, or ‘zone de rencontre’ full of terraces, with speed limits of under 20km per hour being put in place around these areas.

©Ville de Paris

The Paris 2024 Olympics marked the lifting of a century old ban on swimming in the Seine River.

Recovering the River: Rehabilitating Industry as Nature

Let’s leave the Rivoli Street, for a quick stroll by the Seine River, in the direction of Austerlitz Station. Of course, Paris is far from being a pedestrian paradise. On rainy days, over-congestion dominates the trains, with runoff bubbling up from the metro sewers. Hidden corners on the banks of the Seine River still stink of urine, and, the city is still quietly battling with the ominous threat of terrorism. Against this backdrop emerges Paris City’s most ambitious, and in some respects foolhardy, Olympics legacy project.

Improving the water quality of the Seine River to host open water swimming events is the de facto legacy project that has garnered the most media attention for the Paris Olympics. The Bassin of Austerlitz, capable of holding up to 20 swimming pools worth of sewage water was built to prevent waste water overflowing into the Seine River during sudden rainfall. On top of this, houseboats on the Seine River, as well as upstream Parisian suburbs have all taken part in an accelerated effort to reconfigure their sewage systems. As if anxious about the backlash to what could amount to a 1.4 billion EUR ‘pipedream’, top tier politicians, including the French president, minister of sports, and mayor of Paris all pledged to go swimming in the Seine River, to which the chronically dissatisfied French public responded by threatening to relieve themselves in the Seine River at the most opportune moment. While the Games saw the successful hosting of the Triathlon and 10km marathon swimming contests, the opening ceremony was marked with 15 days’ worth of downpour in the space of a day, resulting in the cancellation of several practice runs, and with one athlete withdrawing from the mixed relay after having vomited from a previous race. (It was later announced to have not been caused by e-coli.)

Can we gauge such a feat as an Olympic legacy? The greater vision for the city is to eventually open up the Seine River for public swimming in summers, by exploiting the Olympics to carry out the necessary works. Yet, this challenge seems somewhat reckless once we understand that fate of the open water swimming contests depended solely upon two bacteria counts – e-coli and enterococci – known to be harmful to humans.

Just how important was swimming in the Seine River? What led to such a far-fetched plan to be put into action? The Seine River suffered from mounting and intense pollution from 1910s to the 1980s, followed by a period of respite in the 1990s and 2000s, in which it eventually plateaued. It could have been hoped that mounting media and political pressure surrounding the Olympics could help push the Seine River cleanup efforts over this plateau. It might have been hoped that redefining a once off-limits place as a somewhere where people could jump in and get wet could help people perceive the river as an urban resource for leisure, even if the water was not entirely clean. What they must have needed was to put on a spectacular show, to create the momentum needed to shift perceptions of what the architect Dominique Perrault describes as ‘a transition from industrial to natural resource, whereby the Seine River is requalified as a sort of ‘umbilical cord’ of Paris.’

The project has therefore involved within the context of the Paris City setting up sandy beaches in summer on the banks of the Seine River since 2002, banning car circulation from 2016, and opening up select spots for bathing since 2021.

Ahead of the public in the ‘marathon for all’, marathon runners pass through Vendôme Plaza on their way to the Versailles Palace, in a quest to complete 42.195km. ©Valentin Chesneau , Ville de Paris

Cultural Heritage as a Sports Arena

For travelers, upon completing visits to the Louvre Museum, the Orsay and the Orangerie Museums, a quick stop at the Champs-Élysées Street and the Arc de Triomphe is the ordre du jour. The Arc de Triomphe high at the tip of the Grand Axe, as if to mark the evolution of the urban fabric in Paris, yet doubts remain as to whether the Champs-Élysées Street, now overrun by tourists and luxury boutiques, can still be seen as ‘the world’s most beautiful avenue’.

The Paris 2024 Olympics were launched with a bold vision to use the entire city as an arena, by drawing upon Paris’ vast cultural assets. Yet, something else can be detected behind the scenes: a desire to use the games as an opportunity to experiment with what would normally be deemed daring—more precisely, rehabilitating the city’s historical axes into a more pedestrian-oriented environment. Let’s take the Grand Palais, Alexandre III Bridge, and the Concorde Plaza, where respectively, fencing, judo, triathlon, 10km marathon swimming, BMX, breaking, 3 × 3 basketball and skateboard took place. The historical axis of Paris stretches from the Louvre Museum, the Tuileries Garden, Concorde Plaza and the Champs-Élysées Street, leading on to La Defense. Another smaller axis branches down from the Élysées Palace, towards Concorde Plaza, squeezing in between the Grand Palais and Petit Palais, reaching over Alexandre III Bridge towards Les Invalides. Several key junctures here suffer from disruptions in pedestrian circulation, with the Concorde Plaza functioning as a massive roundabout, and eight lanes of traffic dedicated to cars on the Champs-Élysées Street. Only 5% of visitors on the Champs-Élysées Street, once dubbed the Grand Promenade, are locals seeking leisure.

Curiously, it is not the public sector, but a private sector group – the Champs-Élysées Street Committee led by local businessmen – which has launched this initiative to renew the walking environment. First founded by the founders of Louis Vuitton, the committee is now receiving the full-fledged backing of heads of French luxury brand conglomerates like LVMH. A specially requested urban diagnostic has given way to proposals such as the reduction of eight car lanes into four, reconfiguration of the sidewalks with trees and vegetation, with a completion date of 2030 on the table. Moving downhill to the Concorde Plaza, the Paris City is proposing its own ways, numbering a dozen, of regenerating the plaza. Adding greenery and permeability to the mineralised plaza will pave the way for half of the plaza to reintegrate and extend the Tuileries Garden. Once a place where Marie Antoinette and countless others lost their heads, the plaza will regain its role as a place of gathering for the people of Paris.

The installation of temporary arenas using cultural landmarks has the double impact of promoting tourism while reducing its environmental impact. Furthermore, the site-specificity of each site has been taken into account. Equestrian dressage and jumping, as well as the five sports of the modern pentathlon – fencing, jumping, running, and shooting – was hosted in the gardens of Versailles Palace, while archery took place on the Esplanade des Invalides, a former military hospital-turned military museum housing Napoleon’s grave. The hosting of the opening ceremony on the Seine River, or the ‘marathon for all’, where the pubic were granted the opportunity to run in the footsteps of the marathoners from Paris to Versailles Palace (albeit creating traffic complications for locals), all demonstrated how the city can become a live arena.

The Paris 2024 Olympics opening ceremony took place under torrential rain, backed by a strong sense of ‘the show must go on’, eliciting harsh criticism from near and far. To this, some pundits fought back to advocate for the ceremony and disparage its critics as ignorant of French history or culture. All due to the fact that it is often a challenge explaining why and how some things happen in France. Following this line of thinking, one can easily imagine the city’s current urban policies being dismissed as idealistic, or even reckless, especially by those who have not experienced the city first hand. Yet, if one spends a couple of sleepless sweltering nights without air-conditioning, and all because the city imposes strict regulations on the installation of outdoor units, then perhaps it becomes easier to understand this strange desire to jump in to the Seine River. If one can understand how what once used to be ‘the most beautiful avenue in the world’ has become overrun by cars and tourists and castigated as a sort of no-man’s land in the public memory, perhaps, it becomes easier to accept that any means, even a hefty push from the private sector, can be called in a quest to recover its former glory. If one has ever lived in this city, Europe’s densest capital, with less than 31m2 average living space per person (Seoulites benefit from 35m2 average per person) perhaps it becomes easier to understand why people might want to give their children the liberty to run and play, at least during the school run. As can be seen from some of the reviews of this year’s Olympics, the French are often mistaken to be showing off, to be engaging in demonstrating their superiority over others. Yet, perhaps, the Olympics served as a legitimate excuse to experiment with what would normally judge to be too bold or shocking, specifically breaking ties with the car-centric city. One might even play with the idea that the essence that lies behind this spectacular show, is in fact a number of ideas and experiments on how to plan for hot summers without going against nature. As such, it is hoped that the legacy of the Paris Olympics is that they will be remembered, not so much as a matter of national pride, but for its seemingly modest yet revolutionary effort to change everyday life in the city.

An urban park housing over 40,000 seats was installed as a temporary venue at the Concorde Plaza. ©Josephine Brueder, Ville de Paris

As of 2024, more bike lanes are being installed in Paris, over 1,300km inner city and 4,000km connecting to the nearby suburbs. ©Josephine Brueder, Ville de Paris