SPACE May 2024 (No. 678)

In the heart of Seoul, behind Gyeongbokgung Palace and up a little hill, the Baegundongcheon Stream flows and the remains of a house from Korean Empire era belonging to an independence activist can be found. Although the waterway is now buried under the road and only the site of the house remains, making it difficult to envisage, there is someone who argues that restoring this area’s ecology and history is crucial to reclaiming Seoul’s identity. Last February, after receiving a call to SPACE, we met Heo Seogoo (principal, Heo Seogoo Architects). According to him, the Baegundongcheon Stream area is currently at risk of being bought and developed by private developers. He is active in spreading awareness because he fears that the story of our land might be lost forever. Let’s hear more about the story he wants to protect and what further issues need to be addressed.

A large engraved rock that Kim Gajin marked with ‘白雲洞天 (Baegundongcheon)’ in 1903 still remains in the upper reaches of Baegundongcheon Stream.

The site of Baegunjang, where Kim Gajin lived and worked until his exile to Shanghai in 1919

Youn Yaelim (Youn): The Baegundongcheon WaterWay Park Masterplan (hereinafter the WaterWay Park Masterplan) is a proposal to turn the area around Baegundongcheon Stream and the site of Baegunjang in Jongno-gu of Seoul into a public park. Baegundongcheon Stream is known as the source and the longest tributary of the Cheonggyecheon Stream, but its existence is hardly noted today since most of it is covered, except for some parts upstream. What drew your attention to this place?

Heo Seogoo (Heo): It all started when I learned about the history of this land. The area around Baegundongcheon Stream and Baegunjang intertwines traces of the Joseon Dynasty’s noble classes and a four-generation family history of independence activists. Baegunjang is known to have been built by Kim Gajin (1846 – 1922), a Minister of Justice during the Korean Empire, who after refurbishing The Secret Garden of the Changdeokgung Palace, was granted leftover materials and land by King Gojong. The plaques at Aeryeonjeong and Gwanramjeong pavilions in Changdeokgung Palace bear Kim Gajin’s writings. Kim was active here until he fled to the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Shanghai. A large engraved rock that he marked with ‘白雲洞天 (Baegundongcheon)’ in 1903 still remains. However, during the Japanese occupation, the ownership of Baegunjang transferred to the Oriental Development Company. Although a lawsuit for its return was raised, it was halted after Kim’s exile to Shanghai in 1919 and his death in 1922. After liberation, Kim’s descendants tried various efforts to reclaim the confiscated Baegunjang, but it was halted again in 1950 when his son, Kim Euihan, was taken to North Korea, and during the May 16 coup, the property was sold to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereinafter LDS Church). Since then, the LDS Church has been actively seeking to sell and develop the site. The descendants have long tried to reclaim the meaning of this land. That’s when they approached me for counsel, and thus began our present journey.

Youn: It’s fascinating that the plan began with a private narrative that was scaled up to address public discourse.

Heo: The historical narrative sparked my interest in this region, and one story led to another, like unraveling a spool of thread. Baegundong was one of five scenic spots to be found in Hanyang (old Seoul) during the Joseon Dynasty period, along with places like Inwang-dong and Samcheong-dong. Originating near the Changuimun Gate and flowing between the gate mountains of Hanyangdoseong, the Seoul City Wall, Bugaksan Mountain and Inwangsan Mountain, Baegundongcheon Stream’s landscape has been recorded through ages. Indeed, it appears in poetry recited by Joseon Dynasty scholars such as Kang Huimaeng and in the landscape paintings by Jeong Seon of the late Joseon Dynasty period.

From an academic perspective, a range of significant documents exist including the topographical maps made by the Japanese Government-General of Korea, Baegunjang’s architectural blueprints for repair in 1954, documents from the lawsuit after liberation, survey maps for property claims, various photos, and articles. All these trace how this land and space have evolved over the course of modernisation. It’s rare to find such a culturally and academically rich repository.

The current cadastral situation of the Baegunjang area shows no significant changes since the first modern survey in 1912, probably because it includes several green conservation areas and is occupied by a religious facility. What’s now a road used by a million cars a month still connects rocks underneath and has water flowing. If you listen carefully at the manhole in front of Yoon Dongju Literature Museum, you can hear the water! (laugh) The deeper I delve into the story, the more potential and possibilities I see as an architect for this area. And I felt that a public approach, rather than a private one, was necessary. The restoration of historical, ecological, and environmental lineages through waterway recovery is urgent. If the land is sold and developed, it will be a dream lost forever. We rally with the descendents to tap on the public conscience.

(left) Jeong Seon’s Baegundong from the Jangdongpalkyeongcheop, depicting the landscape of Baegundong among eight scenic spots around Inwangsan Mountain and Bugaksan Mountain (National Museum of Korea collection), (right) A photo postcard of Baegunjang estimated to have been produced around 1925 by the Oriental Printing Company in Gyeongseong

Youn: It’s a public plan, but it’s impressive that it started with an individual’s voice and bloomed. How are you advocating your views?

Heo: We began weaving the story of Baegundongcheon Stream area more tightly into our plans, considering not only architectural and civil engineering values but also humanities and environmental possibilities. In fact, the restoration of Baegundongcheon Stream as the origin of Cheonggyecheon Stream has been a topic across various plans, including the ‘Cheonggyecheon 2050 Masterplan’ announced by Seoul in 2013. However, because there’s not enough consensus on its importance, actioning actual plans and galvanising support has been sluggish. Therefore, spreading awareness of its potential and broadening consensus was a priority. I thought it essential not only to argue this verbally but to show people our ideas through illustrations so they can imagine and sense its value for themselves. Thus, I started conceptualising and drawing my own plan.

Youn: The main concept behind the WaterWay Park Masterplan is to expose the rock and reconnect the waterways. I’d like to hear what potential you found in the land as an architect.

Heo: The upper region of Baegundongcheon Stream is a top-rated ecosystem conservation area, where human intervention has been minimal for a long time, preserving an excellent ecological environment. Although now hidden by topsoil and fallen leaves, removing them would reveal Seoul’s original topography and waterways. This unique topography and waterways are Seoul’s identity and story. It’s rare for a city to be surrounded by mountains like Bukhansan Mountain, Dobongsan Mountain, Bugaksan Mountain, and Inwangsan Mountain, which are connected as a united mass of granite. Despite this, it seems there aren’t many opportunities for citizens in central Seoul to truly experience and interact with this environment. In cities like Kyoto or London, small waterways of about 30 – 50cm wide naturally coexist along the streets where people walk, play, and work. Likewise, if Seoul could reconnect the disrupted upstream and downstream of Baegundongcheon Stream, restore the original appearance of the rock mountains damaged by Jahamun Tunnel, and make parks around the surrounding areas, it could enhance the environmental value of a city where mountains and water coexist.

There is notably no proper entrance to Inwangsan Mountain now, but if the WaterWay Park Masterplan is realised, it could serve as an entry corridor to Inwangsan Mountain. Also, I see geographic and programmatic connections with the nearby Cheongun Literature Library as feasible.

Youn: The WaterWay Park Masterplan consists of five Water Pavilions and three Book Pavilions. What kind of park did you imagine and outline?

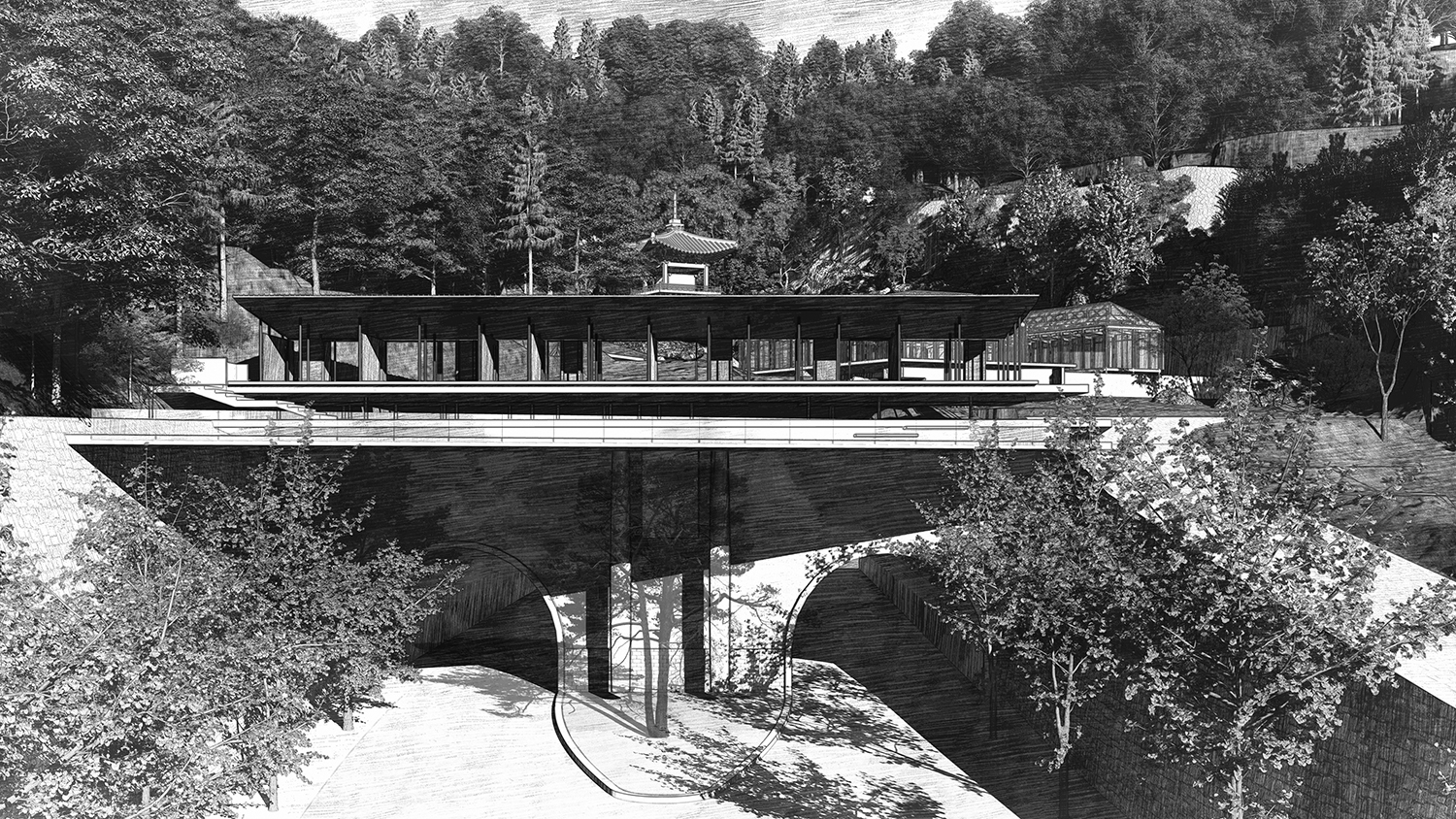

Heo: I imagined a downtown retreat, an invitation to the forest from the busiest part of the city, and a park for reading books. Along the original waterways, across the topography, and throuhgout the Baegunjang site, the Water Pavilions and Book Pavilions form a ‘WalkWay’. Jahamun Mangakru where one can look down at the city and overlook Bugaksan Mountain, and rest areas with the park as its backdrop, a sunlit and breezy library and exhibition hall are planned. Each space is more of a pavilion that houses water features rather than a building. From the Springhead at the top of the site down to traces of Kim Gajin at Mongryongjeong and the engraved rock, Baegunjang, and the Reservoir and Waterfall Pond, these water spaces recreate the waterway of Baegundongcheon Stream. I proposed restoring the structure and space of Baegunjang based on thorough research. It could also serve as a space for collecting, analysing, and displaying various materials and documents related to Baegunjang. In this design, the structure follows the form of a hanok but planned with a transparent exterior so that the trees in the forest themselves form the roof, exposing the beauty of the wooden structure. This specific imagery was designed around the themes of Water Pavilions and Book Pavilions. However, the role of my drawings is just to suggest one possible direction, not to suggest it must be designed this way. The important thing is that the stories contained in this plan may lead to further stories. I hope more supporters who also think about the values and direction proposed by the WaterWay Park Masterplan and have thoughts and plans for the future will join us.

The site plan of Baegunjang (material courtesy of descendants of Kim Gajin)

The site plan of the Baegundongcheon WaterWay Park Masterplan

Youn: What’s the reaction from public institutions and those in surrounding areas? I’m curious about the current status of the project.

Heo: We’ve visited and knocked on every possible door with the descendants. We’ve met the Seoul City Architect, contacted the media, and even visited the offices of National Assembly members. We’re trying to garner support to expand the outreach of this issue into the public domain. The Green City Leisure Bureau of Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG), which previously worked with me on the Oil Tank Culture Park (2017) project, also reached out after seeing a newspaper article. Thanks to this contact, we could discuss realistic obstacles with the city’s relevant departments. On one occasion, I presented the plan and hosted a discussion as part of a meeting attended by Mayor Oh Sehoon and his directors. We’ve also discussed it with the Jongno-gu Mayor. Although the reactions have been positive, linking it to the budget has led to various practical questions and issues. However, I never thought it would be resolved all at once. We’re trying to form a consensus and create a positive atmosphere step by step. We are also continuing to reach out to the LDS Church. If the property is sold to a real estate operator, irreversible development will surely proceed, so the most critical issue right now is to prevent that from happening.

Youn: Is there a way to stop it?

Heo: The way to do it is to publicise and spread the story widely. When a religious corporation sells land, the city’s approval is ultimately necessary. SMG is somewhat aware of this issue. From what I’ve heard, the LDS Church is making its own attempts to resolve its issues, including contacting the U.S. Embassy. Depending on the situation, I’m considering visiting the LDS Church in the U.S.

I’ve already sent a letter suggesting we talk more after explaining the historical and environmental value of the land. Besides, we are continuously trying to expand and publicise the project in various fields. We’ve thought about running projects on this topic in university architecture studios and considering citizen campaigns such as fundraising.

We’re planning seminars and forums within the architectural community.

I’m concerned about how actively architects will participate. We are trying to collaborate with people who are active near Baegundongcheon Stream.

Youn: It seems that gaining greater public awareness and sympathy is the priority right now. Please tell us about the development plan going forward.

Heo: If society, including the architectural community, can take interest, I believe it won’t take long before realising the plan and preventing indiscriminate development. We’ve made meaningful steps so far, and now we’re reorganising to keep moving forward. I confess, the endpoint of the project would be literary, specifically a novel. Whether the setting of the story is in the past or present, whether I am the narrator or someone else, or what form it will take, I’m not sure yet.

I want the completion of the project to be literary. If there was to be a refined story about our own cultural sites, it itself would become a cultural asset. If this project could lead to the formation of a cultural asset centred around Baegundongcheon Stream and Baegunjang, starting from there, more stories could be created, and more people will come to discuss a progressive tomorrow.

Perspective view of Baegunjang from the Baegundongcheon WaterWay Park Masterplan

Perspective view of Jahamun Mangakru from the Baegundongcheon WaterWay Park Masterplan