SPACE May 2024 (No. 678)

Alongside the building and relocation to Gwacheon of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) – Korea’s first contemporary art museum – in 1986, the Korean art museum scene boomed with the opening of the Arko Art Center (formerly Misulhoegwan, 1979), Whanki Museum (1992), Busan Museum of Art (1998), and Art Sonje Center (1998). These buildings are now three or four decades-old and need to be renovated. What should be the directive for the renovations of these old art museums regarding today’s changing demands in terms of their roles and spaces with basic repair? In this report, we review how art museums in Korea have approached the need for renovation and study some examples from the western world as potential reference points.

①Old Art Museums in Korea: Opening to the Audience

②Art Museums in the Postmodern West: From Preservation to Expression

Exterior view of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) Gwacheon (1986) Image courtesy of MMCA / ©Park Junghoon

The Transformation of Art Museum Architecture

The stories behind the new designs of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA) Gwacheon and MMCA Seoul, which were built 25 years apart, give a clear overview of how art museums were perceived differently across different eras. MMCA Gwacheon was finished around the time of the 1986 Asian Games and 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. MMCA Gwacheon was deliberately placed at a relatively inconvenient location beside Cheonggyecheon Stream (which meant it was only reachable by passing through the separately managed Seoul Grand Park) because its topmost priority was ‘worldclass scale’. Another project that was deeply tied with Korean social politics, Busan Museum of Art was built when the leadership of cultural revival was transitioning from the state to the local autonomous government after the opening of MMCA Gwacheon and 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Meanwhile, as Mihn Hyunjun (professor, Hongik University) – who was a winner of the design competition for MMCA Seoul – said as MMCA Seoul opened in 2013 (covered in SPACE No. 551), the role of art museums has evolved from its past role as a ‘monument’ and ‘white cube’ that houses artworks. Mihn’s assertion that ‘locational specificity’ which delivers a unique experience tied to that particular place will replace ‘white cube’ as the future ideology of art museums▼1 echoes what Isozaki Arata said in 1991 about ‘Third Generation Art Museum’. Mihn also added: ‘for art museums to survive in this ‘era of spectacles’ where anyone can access huge amounts of information via the internet and share images across the world, the focus must now be placed on fostering the ‘small-scale relationships’ between the audience and artist as proposed by Nicolas Bourriaud.’▼2 Lastly, in an effort to make the art museum comfortable for any visitor regardless of the purpose of their visit, a design that resembles a ‘park-like architecture, landscape-like art museum’, and non-restrictive movement flow that allows visitors to go about freely to their preferred exhibitions were implemented in MPART SIAPLAN Consortium’s design of MMCA Seoul. Regarding the changing trend for a more visitor-friendly art museum, visual culture theorist Yoon Wonhwa noted that ‘art museum architecture […] is increasingly being thematised as a popular tourist destination with the quantitative expansion and qualitative change in the art museum scene during the latter half of the 20th century,’▼3 and sociologist Catherine Balet observed that ‘art museums are being turned into cultural complexes.’ Going even further, critic Claire Bishop drew attention to how the ‘expansion of sharing of photos and videos via smartphones and social media have changed the genre of artworks in art museums into a dance-like event’ and added that ‘unlike typical performances, artworks operate for long hours at every corner of the art museum, and audiences can view them indiscriminately as they busily pass by.’▼4 This implies that art museum architecture, like café architecture, can also place higher emphasis on how it appears and gets shared on social media than on its exhibition experience.

Exterior view of Seoul Museum of Art Seosomun Main Branch (2002 renovation) Image courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art / ©Kim Yongkwan

The abovementioned ‘qualitative change’ in the art museums as observed by Yoon Wonhwa manifested as part of each art museum’s response to its respective situation. For example, MMCA Gwacheon transformed its circular exhibition hall on the second floor – which was previously used for sculpture exhibition – to a children’s art museum in 1997 to go beyond its basic functions of collecting and preserving art (which was the primary role of an art museum during that time) and equip itself with other exhibitions and educational programmes to satisfy the various public demands. In 1998, when programmes related to film were still limited to film festivals, Art Sonje Center designed its basement as a theatre. In the 21st century, Seoul Museum of Art not only readily implemented a branch system and opened SeMA Bunker (2017) and SeMA Nam June Paik (2017) as footholds in areas with limited access to art, but also more recently designed Art Archives, Seoul Museum of Art (2023) and Seoripul Open Storage (yet to be constructed) as means to resolve the limited storage space problem and newly introduce the archive.

While the role and space of art museums have transformed through active reflection on popularity, public use, and efficiency, discussions on the mutual relationship between exhibition form and space were relatively lacklustre. Observing this lack of interest toward curatorial discussion in contrast to other countries, Lim Keunhye (exhibition manager, MMCA at the time) pointed out that ‘the curatorial departments were respectively installed in 1986 and 2002, years after the openings of MMCA in 1969 and Seoul Museum of Art in 1988’ and inferred that ‘for an extended period of time, curatorship was completely handled by the general administrative team without any professional input.▼5

Exterior view of Whanki Museum (1992) Image courtesy of Whanki Foundation ·Whanki Museum

Exterior view of Busan Museum of Art (1998) Image courtesy of Busan Museum of Art

The Response of Art Museums Facing Renovation

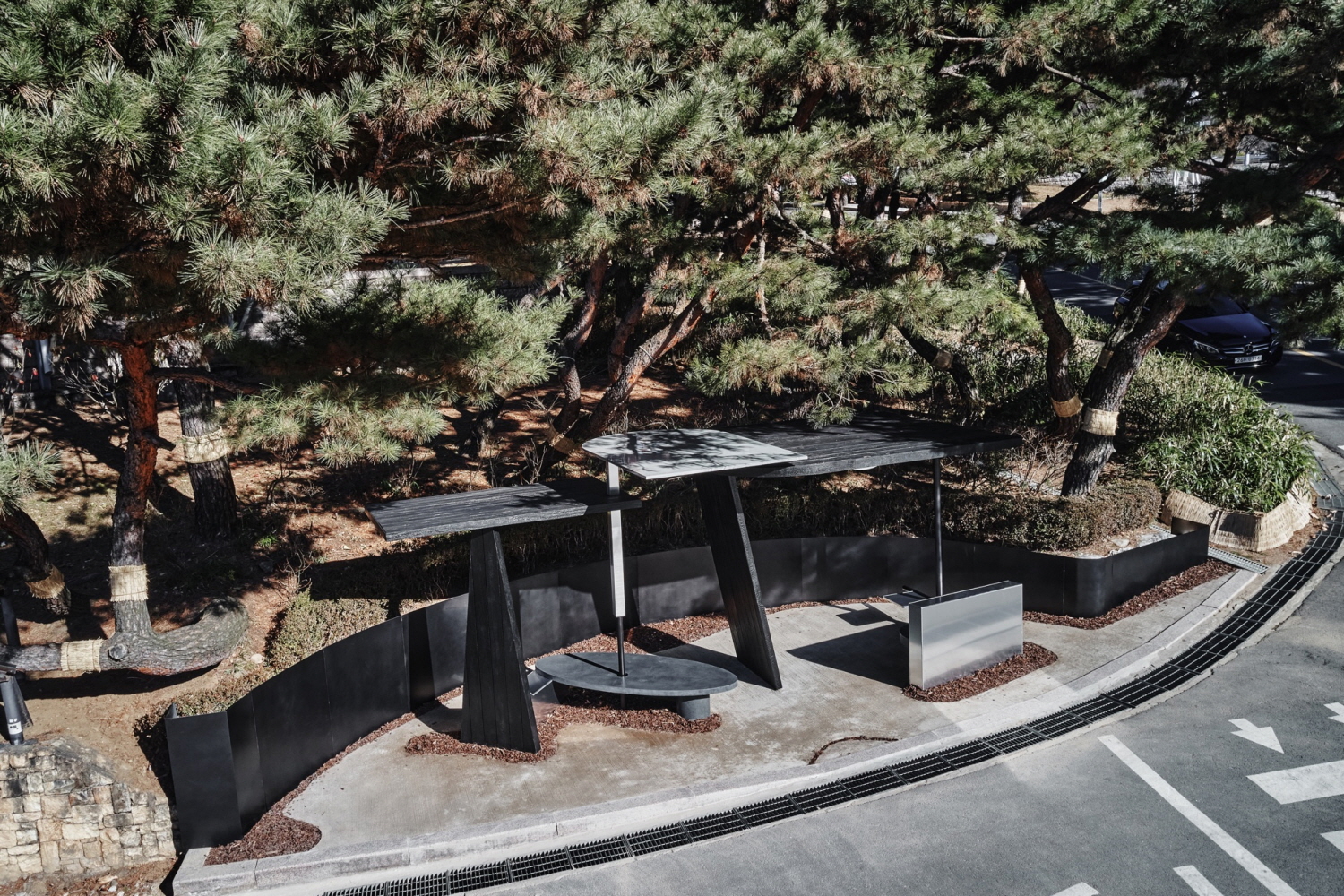

While preparing for their eventual renovations, art museums in Korea began to hold numerous exhibitions with art museum space as a theme, in order to establish connections between their old selves and the contemporary. First, MMCA Gwacheon and Art Sonje Center applied architectural interventions such as pavilions to reframe their original space. Aside from its 30th anniversary exhibition, MMCA Gwacheon also held exhibitions titled ‘MMCA Gwacheon Project’ (2021 – ) and ‘Young Korean Artists 2023: Annotating the Museum’ (2023). During these series of exhibitions, Diagonal Thoughts (principal, Kim Sara) and JOHO Architecture (principal, Lee Jeonghoon) respectively installed pavilions at the bus stop by the entrance (which is one of the main access points for the museum) and at the rooftop garden connected to the rotunda to further enhance the entire museum experience. Also, ATELIER KHJ (principal, Kim Hyunjong) highlighted the museum’s unique architectural characteristics such as its deep space and the use of multiple pillars which was relatively uncommon back then when compared to the wall slab structure. At Art Sonje Center’s exhibition titled ‘Art Sonje Space Project #1-#4’ (2014 – 2016), Choon Choi (professor, Seoul National University), Markus Miessen (principal, Markus Miessen), and artist Jun Yang participated and respectively showcased their works on the first floor lounge space, the main museum entrance, and the hanok buildings that were being used as the art museum’s annex buildings as part of the art museum’s attempt to imbue a new identity to its ‘public space’ within the building.

While there were no architectural interventions in terms of space, there were, however, several exhibitions that used art museum space as theme. Through exhibitions such as ‘Unclosed Bricks: Gap of Memory’ (2018) and ‘Memory·Space’ (2023), Arko Art Museum built up a locational context. The urban scenery of the region around Marronnier Park in Daehak-ro Street where Arko Art Museum is located was first established during the Japanese colonial period when Keijo Imperial University – and later, Seoul National University’s main building, college of arts and science, and college of law – was built along with other modern buildings. With Keijo Imperial University as the start, the exhibition ‘Unclosed Bricks: Gap of Memory’ highlighted the fact that all surrounding buildings were built with bricks, while the exhibition ‘Memory·Space’ reviewed the long history of Arko Art Museum through the eyes of the artists. In face of its upcoming renovation, Seoul Museum of Art also held exhibitions ‘Space Time Scenarios’ (2024) and ‘Weaving Relations’ (2024, refer to p. 10) to reflect on art museum architecture from the perspectives of ‘time’ and ‘weaving relations’ respectively. Through such exhibitions that provoke tangible and intangible enquiries about the significance of art museum space, the museum invited its visitors to share its contemplations toward renovation that go beyond functional matters such as safety, convenience, and energy efficiency to matters concerning the temporality of architecture and the relationship between art and architecture.

JOHO Architecture’s Garden in Time (2022) is a large-scale canopy installation on the rooftop garden. The play of light and shadow across the canopy is different every day depending on the season and weather, enhancing an installation composed of numerous pipes which represent the continuity of a moment and the passage of time. It charts a space-time across which the sensual apprehension of nature and art resonate. Image courtesy of MMCA / ©sugarsaltpepper

Diagonal Thoughts’ ( ) function (2021) explores the anticipation and curiosity one feels before reaching an art museum. Image courtesy of MMCA / ©Park Swan

Architectural Discussion on Renovation

Both Arko Art Museum, which just finished its renovation last August, and Busan Museum of Art, which is currently going through renovation, sought to go beyond mere renovations by changing into museums that are welcoming to their visitors. While replacing its exhibition lighting and renovating the old flooring and walls of the exhibition hall, Arko Art Museum renovated its front space and lounge space. SOSU ARCHITECTS (co-principals, Go Seokhong, Kim Mihee), which renovated the transitional spaces such as the lounge space, opted to preserve the museum’s original simplistic floor plan while positioning unit furniture to meet the museum’s request for a multi-purpose space which, aside from serving as a place where visitors could rest, may also cater for exhibitions and lectures on demand. Busan Museum of Art requested for facility renovation, expansion of exhibition and storage space that totals to 22,000m2 of additional floor area space, addition of a sense of openness toward the exterior, a main entrance that is connected to the underground sunken garden, and expansion of service space that bridges the entrance, lobby and cafeteria. The idea is to enhance the experience of liminal space by stripping away the exhibition hall’s box- like form and the visual boundaries within and outside the museum to build a more flexible space where various two-dimensional, three-dimensional, and media genres can all be integrated.

Along with these renovations that focus on flexible space as response to the increasing number of programmes, exhibitions, and visitors, while simultaneously preserving the original architectural frame, there are also ongoing discussions regarding how one should renovate historical museums with architectural value. Seoul Museum of Art Seosomun Main Branch, which was renovated in 2002 from an old Supreme Court building built with an architectural style of the 1920s, is a registered cultural heritage site that is a part of Jeongdong Cultural History District. To preserve the original façade, expansion work of a total floor area size of 3,000m2 composed of the exhibition hall, storage, and amenities was planned underground instead of aboveground. Just as all work for Art Sonje Center (designed by Kimm Jong-Soung) in 2016 (lobby renovation) and in 2022 (inner staircase expansion and rooftop garden extension) was conducted in close consultation from SAC International (honorary president, Kimm Jong- Soung), the museum stated that it will continue this practice of consulting in its future full- scale renovations. Whanki Museum, which is also currently conservatively replacing some of its old facilities piece by piece without making any new exterior extensions, is also closely communicating with its architect Kyu Sung Woo (principal, Kyu Sung Woo Architects). When MMCA Gwacheon was commemorating its past 30 years with its special exhibition titled ‘Space Transformation Project: Voyage of Imagination’ (2016), Hwang Doojin (principal, Doojin Hwang Architects) showcased his work titled Preserving Space in direct contrast to the exhibition theme. Highlighting how MMCA Gwacheon had been consistently critiqued for lacking the basic infrastructure to exhibit contemporary media art, Hwang defined the contemporary age as a ‘post-plumbing era’ and proposed a method to operate electronic devices with a car battery. He ‘explored the method to cater to the practical needs by utilising cutting edge technology while preserving the building’s core form, organisation, and spatial and structural frame.’▼6. This led to a discussion on MMCA Gwacheon’s past renovations, and Hwang proposed that the museum should ‘accept change but only to the extent that it does not stray too far from its original image and thereby relinquish its chance to become considered as a cultural heritage site in the future.’▼7 As these art museums designed by Tai Soo Kim (principal, TSKP Architects), Kimm Jong-Soung, Kyu Sung Woo, and other architects, which have so influenced Korean modern-contemporary architecture, are starting to approach 50 years of age and thereby pass the minimum condition to be considered as cultural heritage sites, it appears that the ongoing debate is now slowly shifting towards the question on how art museums that ‘are not merely backdrops for exhibiting artworks but are artworks themselves’▼8 should deal with change.

Exterior view of Art Sonje Center (1988) Image courtesy of Art Sonje Center / ©CJYART STUDIO (Cho Junyong)

Jun Yang’s Parallax Hanok (2016) is a conversion of a hanok building, one that has long been used as an annex to the main building, into a café and bar. Junyang raises the question, what role does a café or bar play in an art institution? Image courtesy of Art Sonje Center / ©Kim Sangtae

Choon Choi’s Exit Strategy (2014) is a new corridor connecting two evacuation routes across the lounge space on the first floor of the Art Sonje Center. The corridor, 15m-long and 180cm-wide, has been set at an angle of 40 degrees, which is extremely unfamiliar within the overall spatial layout of the art museum, and serves to divide the lounge space into five establishing new spatial connections with minimal effort. Image courtesy of Art Sonje Center / ©Kim Jongoh

_

1. Mihn Hyunjun, ‘Repurposing and Remodelling the Building into an Exhibition Space’, Monthly Art 469 (Feb. 2024), p. 89.

2. Mihn Hyunjun, op. cit., p. 89.

3. Yoon Wonhwa, ‘Betwwen Architecture and Art: Exhibitin Art Museum Architecture’, Architecture Newspaper, 29 Aug. 2019, http://architecture-newspaper.com/v23-c06-museum/, accessed 15 Apr. 2024.

4. Claire Bishop et al., What do museums change?: Art and democracy, Seoul: MMCA, 2020, p. 9.

5. Lim Keunhye et al., On Curating, Paju: Mimesis, 2019, p. 245.

6. Hwang Doojin et al., MMCA Studies: Art Contemplating Crisis, Seoul: MMCA, 2020, p. 263.

7. Hwang Doojin, ‘Architect Hwang Doojin’s Legacy Place ⑮MMCA Gwacheon’, SPI, 13 Jan. 2023, https://seoulpi.io/article/99972, accessed 15 Apr. 2024.

8. Hwang Doojin et al., MMCA Studies: Art Contemplating Crisis, Seoul: MMCA, 2020, p. 261.

9. With the opening of the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art, Neue Nationalgalerie was repurposed as a museum that houses and exhibits European paintings and sculpture artworks created from the early to mid-20th century. Contemporary artworks that were created after 1968 were moved to the more recently built Hamburger Bahnhof Museum for Contemporary Art.

10. While MoMA had historically carried out collection exhibitions that were separately curated by independent curatorial departments, such as the painting and sculpture department, print and drawing department, and architecture and design department, for the first time in 2015 it attempted an integrated curatorial approach to its 1960s collections. Lim Guenjun, ‘A critical view of history that forms the museum collection line: Building and updating the collection line that weaves and drives the hegemony of art history’, SeMA Coral, 18 Sep. 2021, http://semacoral.org/features/chungwoolee-limguenjun-collection-critical-historiography/, accessed 19 Apr. 2024.

11. Lim Guenjun, op.cit.

12. Twenty years after opening, the Centre Pompidou performed a renovation in 1997 with its original designers Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, with the expansion of exhibition space and improvement of the reception facilities.

13. The co-designer Richard Rogers passed away on the 18 Dec., 2021.