SPACE March 2024 (No. 676)

The role of acoustics is expanding in religious spaces. Nowadays, religious spaces are not just venues for pastors to preach, but are widely used as cultural spaces for the community, accommodating many genres of music. The quality of sound depends not only on the performance of audio equipment, but also on architectural acoustics depending on the shape, structure and finish of the building. SPACE took the opportunity to hold a discussion with Chung Wanjin (principal, OSD Engineering), who has been responsible for acoustic design in various venues such as religious spaces, concert halls, theatres, multipurpose halls, and stadiums over the past 30 years. The interview is about how acoustic design is applied in religious spaces, and what needs to be done to improve the acoustics of religious architecture in Korea, seen through the examples of the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang and Seosomun Shrine History Museum.

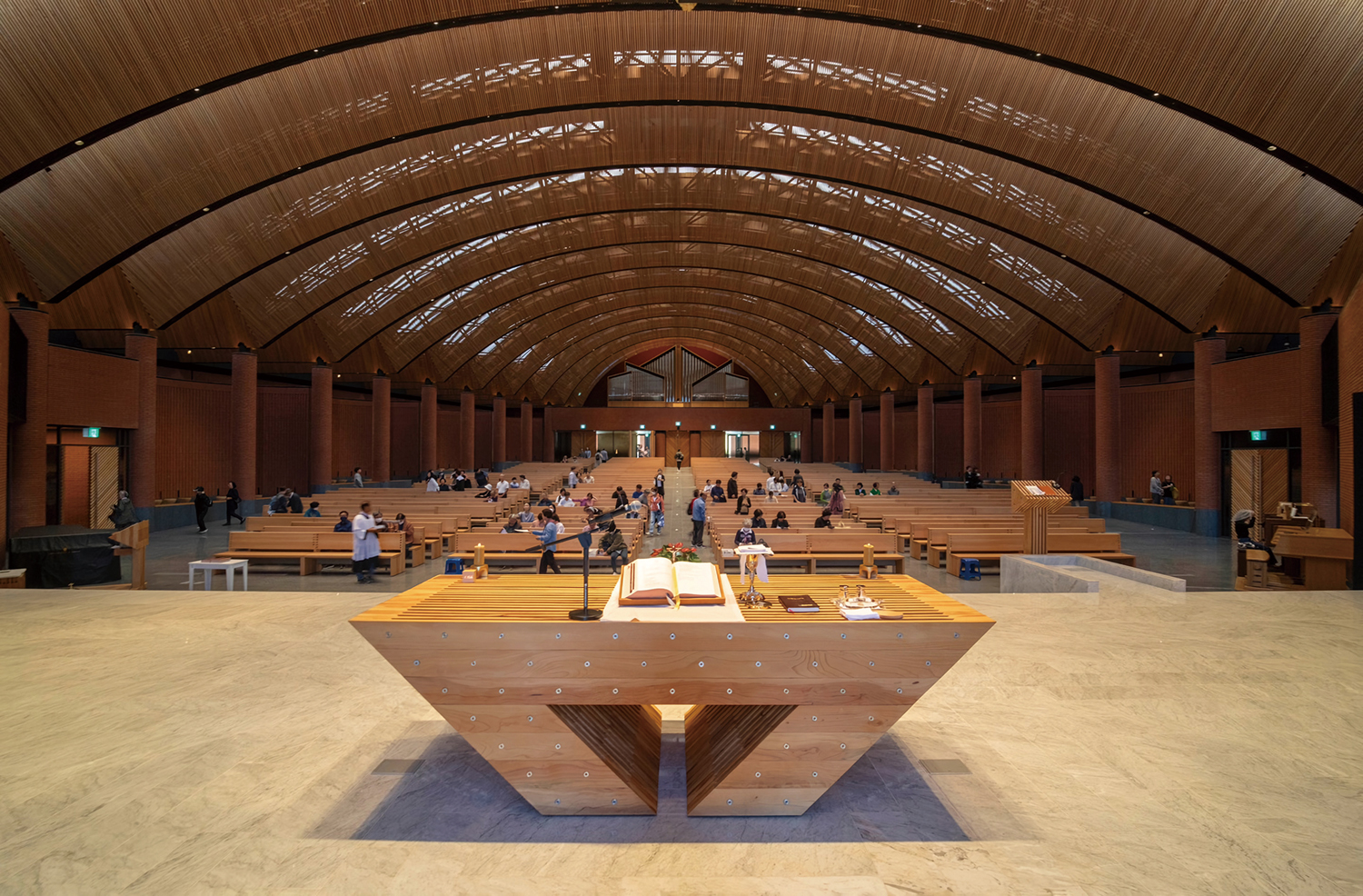

The Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang hosts a variety of performances, including professional orchestras. ©Lee Sanggak

interview Chung Wanjin principal, OSD Engineering × Kim Jia

Kim Jia (Kim): You have designed acoustics for a wide variety of spaces. How do the acoustics of spaces such as concert halls or theatres, where sound is commonly considered primary, differ from those of religious spaces?

Chung Wanjin (Chung): Preaching, praising, and worship in churches are accompanied by verbal communication. Therefore, acoustic design is as important as architectural design in religious spaces. However, over the past few decades, many Korean churches has been focusing on outward appearance, neglecting the acoustic performance within. The acoustic characteristics of a church need to take account of the fact that sermons are delivered and music is played in the same space. Sermons, which are more like lectures, do not require reverberation because they aim to clearly convey the sound of the words, but reverberation is essential for musical performance. Therefore, there are points where acoustic design is more difficult than it would be in a professional performance venue, but non-professionals tend to think that acoustic design in church architecture is relatively easy.

Kim: Could you describe the overall process behind acoustic design?

Chung: The ideal process involves collaboration with architectural design, as the form, finishes, soundproofing, and insulation of a building affect its acoustic properties. Once the purpose and scale of the building have been determined, architects and acoustic designers work together to establish a concept and then proceed to arrange floor plans, the layout of halls and ancillary rooms, and the finishing structure of the spaces in sequence. However, in the case of religious spaces, they rarely collaborate during the design phase and are usually involved after the design is completed. The structure and finishes of walls, floors, ceilings, and so on are considered in order to realise the acoustics of the space in accordance with its purpose.

Kim: First, let’s talk about the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang (covered in SPACE No. 647). It was designed as a religious space for mass and liturgy, but also as a cultural space for various performance genres, so it must have been important to realise high-quality acoustics.

Chung: I was involved after Mario Botta’s initial design was completed. The Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang falls among the larger scale projects of Mario Botta’s religious architectural works, with the initial design even larger in scale than what we see now. Sound interacts with surfaces by being absorbed, transmitted, and reflected. When the floor plan is excessively large, with excessive width and depth, the cosiness, comfort, and clarity of the sound deteriorate. Concerns were raised not only from an acoustic standpoint, but also from an architectural perspective about the large scale. In response, Mario Botta reduced the floor plan by 10m in both length and width and raised the ceilings by about 4m. With the reduced floor plan, early reflections were secured and with the heightened ceiling, later reflections were also secured, resulting in greater acoustic detail, proximity, and richness.

Kim: I heard that the curved surfaces of the side walls and ceiling can be acoustically vulnerable.

Chung: Reflected sounds from a curved surface converge at multiple points, creating uneven sound fields and potentially causing reverberations that can disrupt performances or listening experiences. In other words, strong acoustic focus in the space results in repetitive reflections, leading to an uneven reverberation characteristic. Therefore, curved surfaces contradict the goal of acoustic design, which is to make sound reverberate evenly.

The Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang hosts a variety of performances, including professional orchestras. ©Lee Sanggak

Kim: How did you overcome structural conditions that could create acoustic challenges, such as vaulted ceilings, semi-circular side rooms, and two tall towers?

Chung: First, it was necessary to ensure that sound could pass through the vaulted ceiling of the cathedral, which, if blocked, could cause echoes from reflected sound. Mario Botta and Han Manwon (principal, HnSa Architects & Designers) replaced the ceiling structure with a hollow truss structure and finished it with wooden louvres with an opening ratio of more than 50%. Inside the ceiling, sound-absorbing materials were installed. Thin materials prone to vibration, such as steel plates, had rubber sheets stuck to their backs to suppress panel vibrations. With these changes, reverberation time increased, ensuring proper resonance while dispersing sound returning through the louvres to prevent echoes. Additionally, the side rooms have a semi-circular shape that causes sound to collect. To mitigate this, the architects stacked the bricks in a zigzag pattern and varied the shape of rumbles, creating diffuse reflections that scatter sound to different points. The echoes from the 48m-high tower were prevented by lining the straight, semi-circular sections with perforated sound-absorbing plasterboard. In addition, the auxiliary staircases on both sides of the cathedral and the upper wall of the vestibule space were partially opened to allow performance sound to flow out into the vestibule space and then flow back into the cathedral, thereby realising rich sound by using it as an acoustic chamber.

Kim: The lobby exudes a calm feel, unlike the echoing cathedral. In what ways did you utilise finishing materials differently?

Chung: The hall, which houses mass, liturgy, and musical performances, requires suitable resonance. In contrast, the lobby, which is the first space you encounter upon entering and is a conversational space, should have minimal resonance. Taking this into account, the same finishes were used as in the hall, but with a different attachment structure. The plywood used as ceiling sound-absorbing materials absorbs low frequencies. This ensured acoustic neutrality, that is, a clear acoustic space.

Kim: What was the process of collaborating with architects to develop acoustic solutions?

Chung: The Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang is a collaborative project between the client, architects, and acoustic designers to realise good acoustics. We had in-depth discussions with Lee Sanggak (priest, Catholic Diocese of Suwon), Han Manwon, and Mario Botta about the acoustic deficiencies predicted by the design and found technical solutions to overcome them without destabilising the structure. It was not an easy process, but various entities contributed to enhance the completeness of the structure. The efforts of the operators, who fully understood the design intentions, also played a crucial role. As a result, the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of Namyang hosts a variety of performances, including professional orchestras, and both performers and audiences are satisfied with the acoustics.

Kim: Let’s move on to the Seosomun Shrine History Museum (covered in SPACE No. 623). As a memorial space rather than a church or cathedral, the architecture has distinctive characteristics. What provided a focus for the acoustic design for the main space—the Consolation Hall?

Chung: The architectural design of the Consolation Hall was planned with the context of this being a building erected in a sacred site for Catholics, considering it as a space for contemplation, a place where one can find comfort in silence. Across from the Consolation Hall, an open Sky Plaza is situated. We thought it would be advantageous to leverage the contrast between these two spaces from an acoustic perspective. Considering that it is a cultural space that is both religious and visited by the public, we thought that small concerts and performances could play a role in revitalising the museum. Even if performances are not held all the time, if it is utilised flexibly as a space to occasionally experience cultural events, it could become a building that visitors return to two or three times.

The Consolation Hall of the Seosomun Shrine History Museum is a cube-shaped structure with an open underside. According to this, resonance could occur in the square space constructed of steel, so Chung installed special absorptive materials on the back faces of the four corners to selectively absorb frequencies. / Image courtesy of Seosomun Shrine History Museum

Kim: A performance in a space dedicated to silence may sound a little paradoxical.

Chung: The Catholic Diocese also shared the same concerns. They claimed that incorporating a dynamic performance in a building with religious significance contradicts the design intent of the architectural space. Moreover, the Consolation Hall, which is a cube-shaped structure with an open underside, raised concerns about the potential leakage of sound from cultural events into the open sky plaza or the influx of external audience noise. However, we were convinced that this apparent problem could become an advantage. In the Pyongchang Alpensia Music Tent (2012, designed by SPACE GROUP), for which we were responsible for the acoustic design, natural elements such as wind, rain, people talking, and traffic sounds were incorporated as sound effects and no separate sound barriers were installed to prevent them. We also drew inspiration from Theatre Aspen (2005) located in a disused mining town in Denver, U.S., where during performances, even if strong winds prevented the audience from hearing the performance, it is not considered an acoustic impairment. Natural elements themselves are seen as part of the acoustic experience. This example convinced the architect and the client, and now the Consolation Hall irregularly hosts cultural events such as orchestras and classical concerts.

Kim: Since the space wasn’t designed for performance from the start, there must have been difficulties planning the acoustics.

Chung: In particular, it was challenging to secure effective early lateral reflected sound in the Consolation Hall, which is an open space. Additionally, resonance could occur in the square space constructed of steel, so we installed special absorptive materials on the back faces of the four corners to selectively absorb frequencies. The lattice walls on the four sides and the well-shaped ceiling have high sound diffusivity to compensate for echoes. Lee Kusang (principal, VOID Architects), who designed the Seosomun Shrine History Museum together with Yoon Seunghyun (professor, Chung-Ang University) and Junseung Woo (principal, Less Architects), installed acoustically permeable screens on the four walls in consideration of the acoustic design concept. We designed media art that could be enjoyed alongside music during performances, aiming to enhance the immersion of visitors.

Kim: Acoustics are important, not only in religious spaces, but also in everyday spaces. What are the issues involved in achieving good acoustics?

Chung: Well-designed buildings that can be enjoyed as part of everyday life are increasing in number. However, similar to church architecture, many buildings have a great appearance, but they tend to overlook the invisible but crucial elements of architecture. In other words, while buildings made of exposed concrete are gaining popularity, when exposed concrete is used for interior finishing, excessive reverberation can occur due to its hard and smooth surface. Without addressing such acoustic flaws, the experience of staying in such spaces may not be as pleasant as it looks. Acoustics is a physical phenomenon that you can’t see or touch, but it’s certainly felt. Therefore, if users and designers keep this in mind when experiencing and configuring spaces, there will be more opportunities to encounter spaces with good acoustics in daily life.

The lattice walls on the four sides and the well-shaped ceiling have high sound diffusivity to compensate for echoes. / Image courtesy of Seosomun Shrine History Museum