SPACE May 2024 (No. 678)

After achieving a more thorough understanding of a space through research into its history and narratives, Han & Mona redesigns the identity of a space not only by addressing material elements but also immaterial elements such as light, sound, and scent. This is why, when entering their work, the physical and emotional senses are the first to respond before a more rational or critical engagement with the work. SPACE spoke to Han & Mona about their interpretation of places and architecture and the process behind the realisation of their works.

Exhibition views of ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’ (2023). The hue of the pink light in the morning and afternoon is different.

Interview Han & Mona × Park Semi

Park Semi (Park): Han & Mona is an artist duo based in Edinburgh, U.K., and Seoul. Observing the characteristics of Han & Mona’s work, one is compelled to ask about the personal backgrounds of Hanqing Ma and Mona Yoo. What questions informed your personal growth or emerged from your educational backgrounds in reaching your work, or what cultural backgrounds have you experienced?

Han & Mona (H/M): We are an artist duo living in both Europe and Asia and working in different cities. We use photography, sculpture, and site-responsive practice to explore architectural representations of ruins, decay, and gallery spaces. We are interested in the overlooked and forgotten buildings and how they can be read and understood in architecture from a global perspective.

Han is a Beijing-born ethnic minority (Hui Chinese) and moved to London in his early twenties. Mona was raised and lived in the U.S. and South Korea before moving to London. We met at the Royal College of Art in 2014 and have been working together since then.

The mixture of cultural backgrounds, the perception of diverse and minority identities, and the experience of living across the world have led our research to focus on the liminal space of the ruin and the material poetic hidden beneath. We consider these elements and their potential effect on and impact upon humans and architecture.

Exhibition views of ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’ (2023). The hue of the pink light in the morning and afternoon is different. ©Jennifer Gelardo

Park: The site-specific approach, which is one of the key features of your works, fully reflects the artist’s perspective and attitude towards ‘how to interpret place’. How do you define ‘place’ or ‘site-specific work’? Furthermore, how are these perspectives and attitudes made manifest in your exhibitions?

H/M: Our understanding of ‘place’ is greatly influenced by the cultural geographer Yi-Fu Tuan. He differentiates between ‘space’ and ‘place’ by highlighting the human experience in space. ‘Space’ is transformed into a ‘place’ when humans endow it with value, and when ‘space’ is infused with experience and life attachments, it becomes a ‘place’. We are interested in the empathetic potential of a place. Our site-specific works often respond to such queries, the hidden narrative, the untold anecdotal stories from the forgotten past. In our works, the gallery space is not merely a ‘white cube’ space but a ‘place’ of embodied experience, both visually, materially, and spatially.

The temporal scaffolding structures we built in Interior Deduction (2018) are reminiscent of the constructive and transitional state of the gallery building in 1973, where we imagined the installation abstractly recreating the space that lived in that archive image from the university collection and invited the contemporary audience to experience it through the work. In ‘Place in Reverse’ (2019), the entire old farmhouse, located in a depopulated Japanese suburb village near Niigata, was bathed in amber light, and artificial grasses were placed on the gallery floor to convey how nature had retaken the village, the boundary between interior and exterior becoming unclear, thus, the place transformed back into a space again.

The subsequent projects focused on using ‘windows’ that connect the inside and outside of the building as exhibition spaces. In the work Pause Patina (2022), the gallery windows were obscured with white paint, temporarily halting the space, conveying a remnant of a typical scene we experienced in the U.K. during the pandemic. This work, somewhat similar to the approach in making I am the space where I am (2022), as both works were located in the window space of the gallery. During the daytime, when the exhibition is open to viewers, the artwork’s light and sound are often obscured by the gallery’s lighting, making it difficult to discern both. However, this subtlety reflects the social neglect and sense of alienation that we encountered living in other cities.

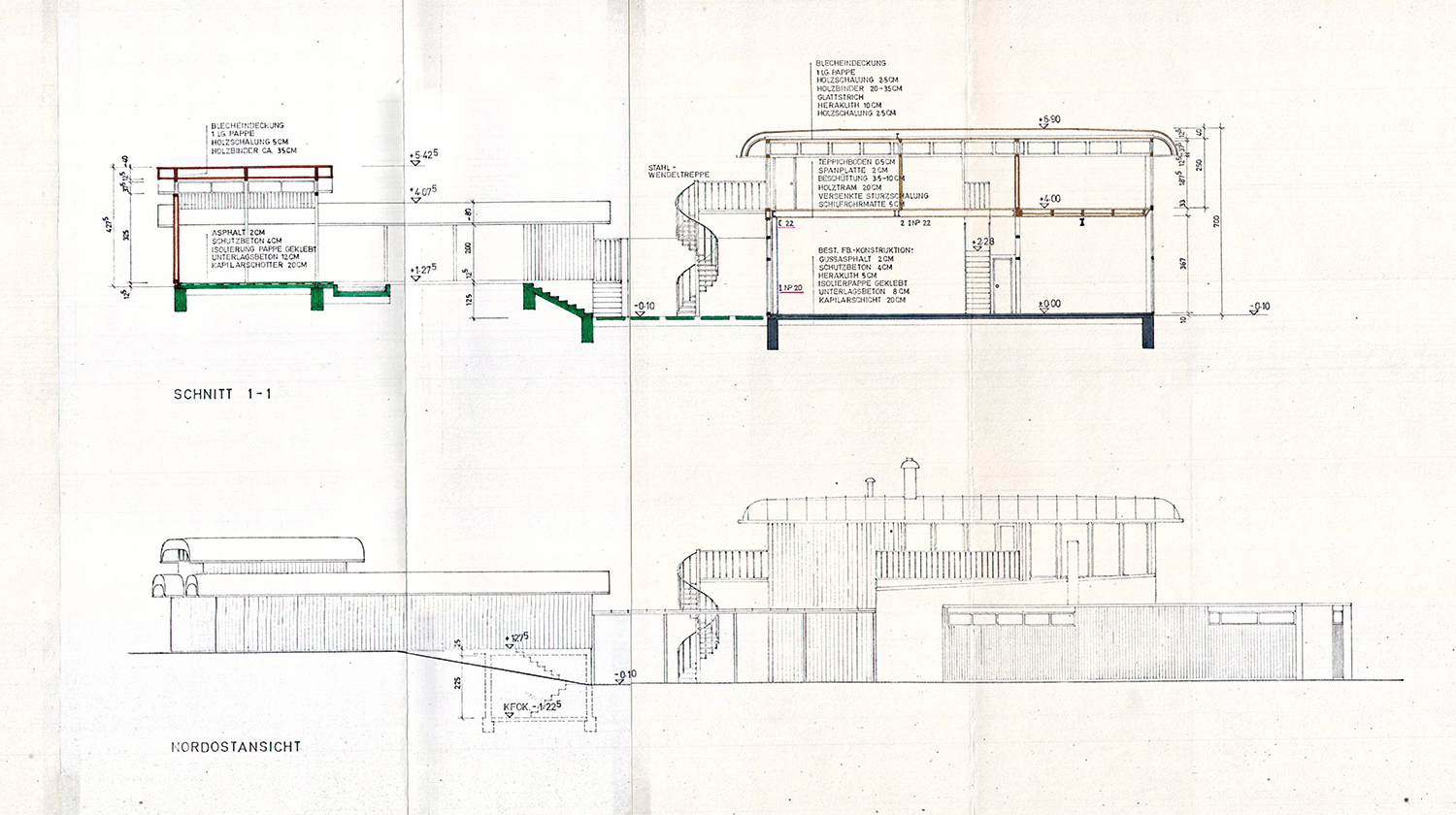

Partial drawing proposed in the original plan (basement elevation of the pavilion, second floor of the atelier) of Echo Correspondence, exhibition space for ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’. Image courtesy of Echo Correspondence

Park: Echo Correspondence, located in Vienna for the exhibition ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’, is also the house and studio where the renowned Austrian sculptor, Waner Bertoni lived. It was designed by Johannes Spalt (1920 – 2010) in the 1970s. What were the historical, cultural, and physical conditions of this building?

H/M: Echo Correspondence in Vienna is situated in a tranquil residential area. It was designed by the architect Roland Rainer in the early 1950s as the home of sculptor Waner Bertoni. Twenty years later, in the 1970s, Johannes Spalt designed the current studio and pavilion buildings. Johannes’s architecture follows the pragmatic functionality of the 1920s modernist architecture and the aesthetic symmetry of Vienna’s traditional Baroque style. Additionally, the design of the villa was also profoundly influenced by Japanese culture and the belief that architecture should be monotonous and transparent. As such, it was an unusual building in Europe in that it has the outward appearance of a Japanese tatami format, but closely follows the aesthetics of Baroque symmetry. For us, the building remained a ‘ruin’ as a ‘place’, being isolated from the outside world for over 20 years after the sculptor’s death, and was not opened to the public until 2022.

As Asians who have lived in Europe for a long time, we naturally felt emotionally attached to the unique situation of this building. Our first thought was to honour the ‘time of the building,’ the long years of lonely, empty, and hard work that it had endured. With the idea of ‘collaborating’ with the building, We were inspired by the drawings of the basement space and the second floor of the atelier, which were planned in the original design but never built. We focused on the sound of silence within emptiness, concentrating on things that existed but were not remembered, just as the title of the exhibition suggests. We intended to read, touch, and listen to the emotions that have been dormant in the building for more than twenty years through ‘sound, scent, light, vibration, dust, and temperature’. Through such tactile experiences, We aimed to reframe the memories of the building. Additionally, the subtle response to the passage of time, with light gentilly changing throughout the day and the pink hue of the lights intensifying at night, serves as a device to reveal the hidden aspects of the building.

Exhibition view of ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’ ©Jennifer Gelardo

Same exhibition as above. If the visitors lean their ear and body against the wall, they will hear the artist’s recorded breathing sound as a vibration wave.

Park: How did the artist interpret the existing space and translate their findings into the present work?

H/M: For us, an existing space is a space that is inhabited with material remnants and a narrative; a sequence of events involving human behaviour that combines space and time. It is a space that preserves all its traces in the passage of time that are waiting to be awakened. It is a space that has been existing, and the space is still holding the sense of ‘being’ within its line, form, and dimensions.

Our work often starts with a period of research on the specific gallery space or building we work with. This on-site research includes taking photographs, measuring the space, and carefully looking into the related documents of the gallery such as historic archives, blueprints, floor plans, and past exhibition leaflets. We often spend time staying at a space to read and understand its own personality of the building. We regard the site as an embodiment of a human, as the Modular by Le Corbusier is transformed into a space. At some point, the space tells us the story, and our role is to listen. Looking back over our past projects, finding the right exhibition space for us was as much a joy as discovering a ruin in the city. We think the key to creating good work is to listen. The making of a good work will not be too hard If there is a good existing space.

Installation view of Interior Deduction (2018) ©Sally Jubb

TBR-1973 (2018). Historic photograph documenting the conversion from a university lecture theatre to a contemporary art museum in 1973. Image courtesy of Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh

Park: It seems that architecture redesigns space through immaterial elements such as light and sound. Morse code, as a language of signals, has also been employed in various exhibitions as one such device. What power do you think immaterial elements have as a medium through which to counteract existing spaces?

H/M: We see immaterial elements as tangible forms and elements that can be used to resemble our experience of ‘being’ in the space. Architect Peter Zumthor said, ‘Architecture […] as an envelope and background for life which goes on in and around it, a sensitive container for the rhythm of footsteps on the floor, for the concentration of work, for the silence of sleep.’ These are things we cannot see nor can be described in words, yet they still persist. It is the sound, smell, touch, and body memory in space that are often beyond the visual and textual, speaking to our inner selves as part of a deeper perceptual and empathetic experience. We employ a phenomenological way of understanding space and architecture.

Morse code is a universal language that translates our words of emotion and sentiment into a simple yet ambiguously significant sign. We later installed this mode of communication in particular exhibition spaces: the threshold of windows (Edinburgh) or the end of a corridor (Vienna). These spaces represent multi-layered words and meanings, transforming them into spatial experiences. We invited the audience to participate in and engage the gallery spaces as well as considering their own relationship with the space.

Exhibition view of ‘Place in Reverse’ (2019) ©Han & Mona

Installation view of Pause Patina (2022) ©Jules Lister

Park: Your works are site-specific, which deals with the unique and fixed elements of a particular place, but ironically, keywords such as ‘stranger’, ‘boundary’, ‘threshold’ feature prominently in your exhibitions. I wonder how you relate your own identity to your actual work.

H/M: Identity is a very complicated topic to delve into. Someone’s floor is another person’s ceiling—we perceive our identities as fluid and adaptive, transcending borders, countries, and cultures. Because of this, in the long term, we might lose a continuous sense of belonging to any place. This has somewhat developed into a recurrent topic in our work over the years. The terms ‘stranger’, ‘boundary’, and ‘threshold’ have therefore been used frequently and resonate with a diasporic and nostalgic sentiment.

Architecture is an effective subject for exploring such complex feelings because it speaks to the relationship between space and humans. In our work, the specific site, gallery, or building becomes both subject and object, helping us to locate ourselves in the process of searching, tracing, and exploring. A building is like nature, rooted in the ground; it remains in place through the day and night, and even seasons; it is a shelter where we find comfort and rest, and where we regain our balance and the strength to work again.

Stills from a film of I am the space where I am (2022). The light and illuminationchanges over time. ©Han & Mona

Park: In a way, it seems like you consider site-specificity to be the foundation of your work, but, in the end, you break it down and move towards universal places and messages. I would like to hear more about the artistic world that Han & Mona inhabit, and want to expand or specify in the future.

H/M: We hope that our work is not limited to a specific region, city, or country, and that it can be read in a universal language from a contemporary perspective. This is why we continue to work in Asia while being based in Europe. For us, site-specificity is no longer a subject or a basis. It is a medium and a pathway through which to realise the concept.

For example, the remnants and ruins of modern cities make visible the history of change that architecture inevitably undergoes but is often forgotten. The ‘unremembered and forgotten’ created and lost in the process of demolition is a contemporary phenomenon in cities of all countries, and we draw attention to the temporal byproducts of this process.

In a similar way, the ‘place of an exhibition’ is also considered as a ‘place of ruins’ with an embedded historical narrative, and the time added to and removed from the existing architectural structure during the installation and removal of the exhibition reveals the sense of place behind the exhibition.

We are currently working with the university’s collections centre on a project that will use AR technology to transform between the real and the virtual. Later this year, we will be traveling to Florence, Italy, with the support of the Royal Scottish Academy and John Kinross Foundation. Most of our works with buildings have been large-scale installations, but we think this programme will allow us to focus on fragments, perhaps encompassing the whole through parts.

View of the ‘There Is Not Even Silence In The Void’ under the scaffolding structure. A 1/50 scale model of the building was installed alongside the remnants.