SPACE April 2024 (No. 677)

Rapid population decline is shaking the fabric of small and medium-sized cities to the core. To rebuild these cities, we need to move away from the inertia of regeneration and take a perspective that acknowledging change. This is where the Mid-Size City Forum comes in. They look at phenomena outside the metropolitan area and seek urban and architectural alternatives to the crisis.

[Series] The Possibilities Inherent in Extinction, Mid-Size City Forum

01 What is Happening Outside the Metropolitan Area

02 Thinning Phenomenon

03 Urban Perforation

04 Erasing Plan

05 Ad-hoc Architecture

06 Global Mid-Size City

07 Resilient Mid-Size City

08 Fantastic Mid-Size City

09 Outside of the Mid-Size City

I once visited a small city in Gyeongsangnam-do as a hiker. The memory of walking down the streets in the middle of the day, waiting for a bus that never came, with no shops open and no pedestrians around, is romantic at first, but in hindsight, it’s a bit sorrowful. It has long since become the norm in many small and medium-sized (hereinafter mid-size) cities. The Mid-Size City Forum explains the causes and phenomenon with the concept of ‘thinning urban concentration’ and imagines a solution that works for Korean mid-size cities with a ‘dual spatial structure’.

New normal condition of mid-size cities

Mid-size cities are going through a lot of changes right now. The most easily recognisable of these is the scene on the street, where there are noticeably fewer people walking around. It is more than just a unique phenomenon in one or two cities. Empty streets are typical in mid-size cities across the country. Why does this happen? Much of the discussion and discourse so far has focused on population decline. But is population decline the only contributor?

In mid-size cities, cities continued to expand in area despite a declining population. As a result, population density within the cities has dropped dramatically. The Mid-Size City Forum is dedicated to addressing the intricate dynamics of population decline and expansion of urban areas. Through their analysis, we aim to explain the effects of these phenomena, such as the thinnig of population densities and the erosion of urbanity, on mid-size cities across the country.

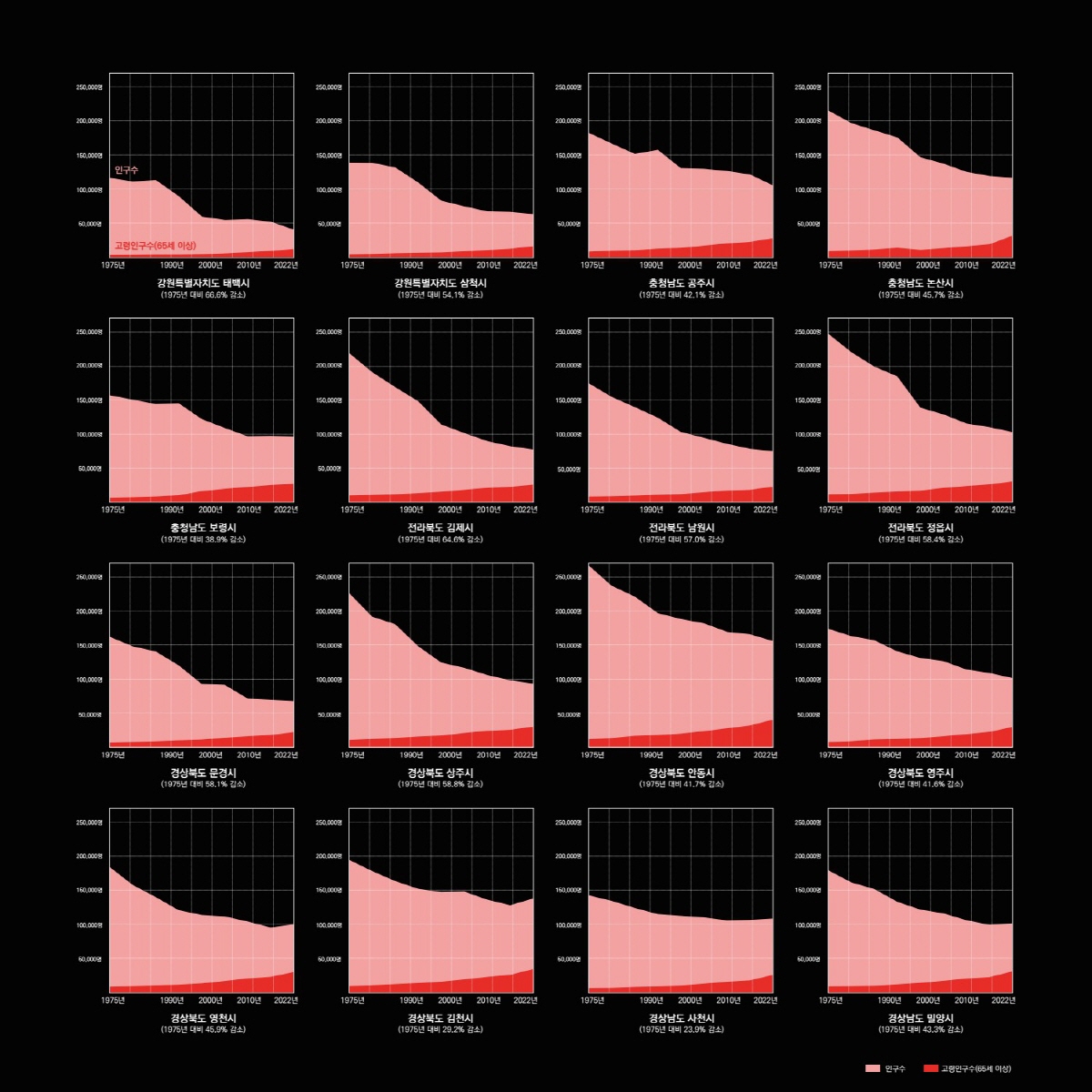

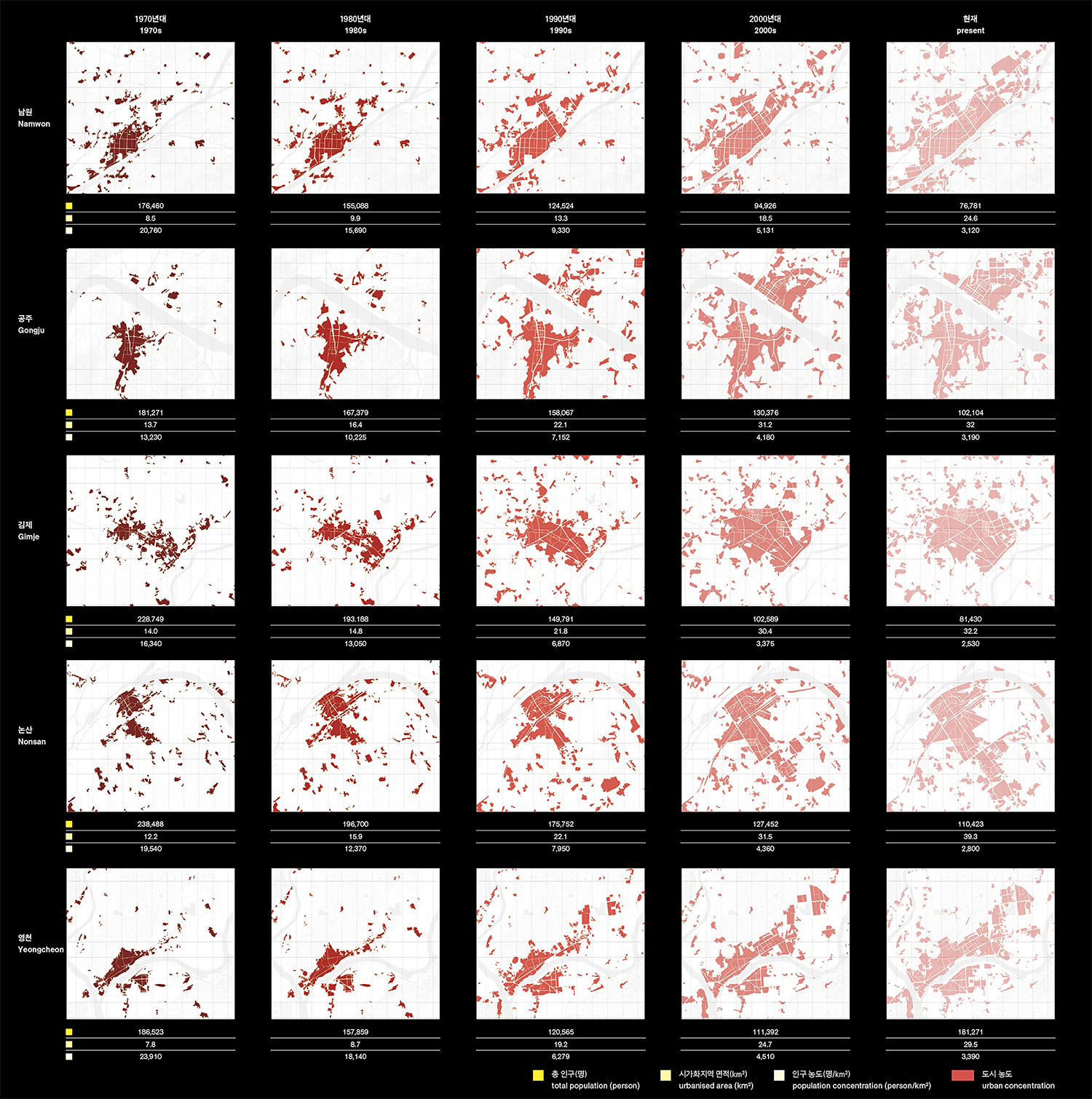

Changes in population, urbanised area, and urban concentration of mid-size cities (1970s – present). Cities continued to expand in area despite a declining population.

Population

The population of rural mid-size cities has been declining steadily over the past 50 years. According to statistics, as of 1975, Namwon, Jeollabuk-do had a population of 175,203, but the current population is 76,781, a decrease of 56.2% from 1975. The population of Gimje in Jeollabuk-do; Yeongcheon, Mungyeong, and Yeongju in Gyeongsangbuk-do; Jecheon in Chungcheongbuk-do; Nonsan and Gongju in Chungcheongnam-do; and Samcheok in Gangwon-do have decreased in population by 63.2%, 45.7%, 57.3%, 42.4%, 23.4%, 48.7%, 44.2%, and 55.3%, respectively, compared to 1975.

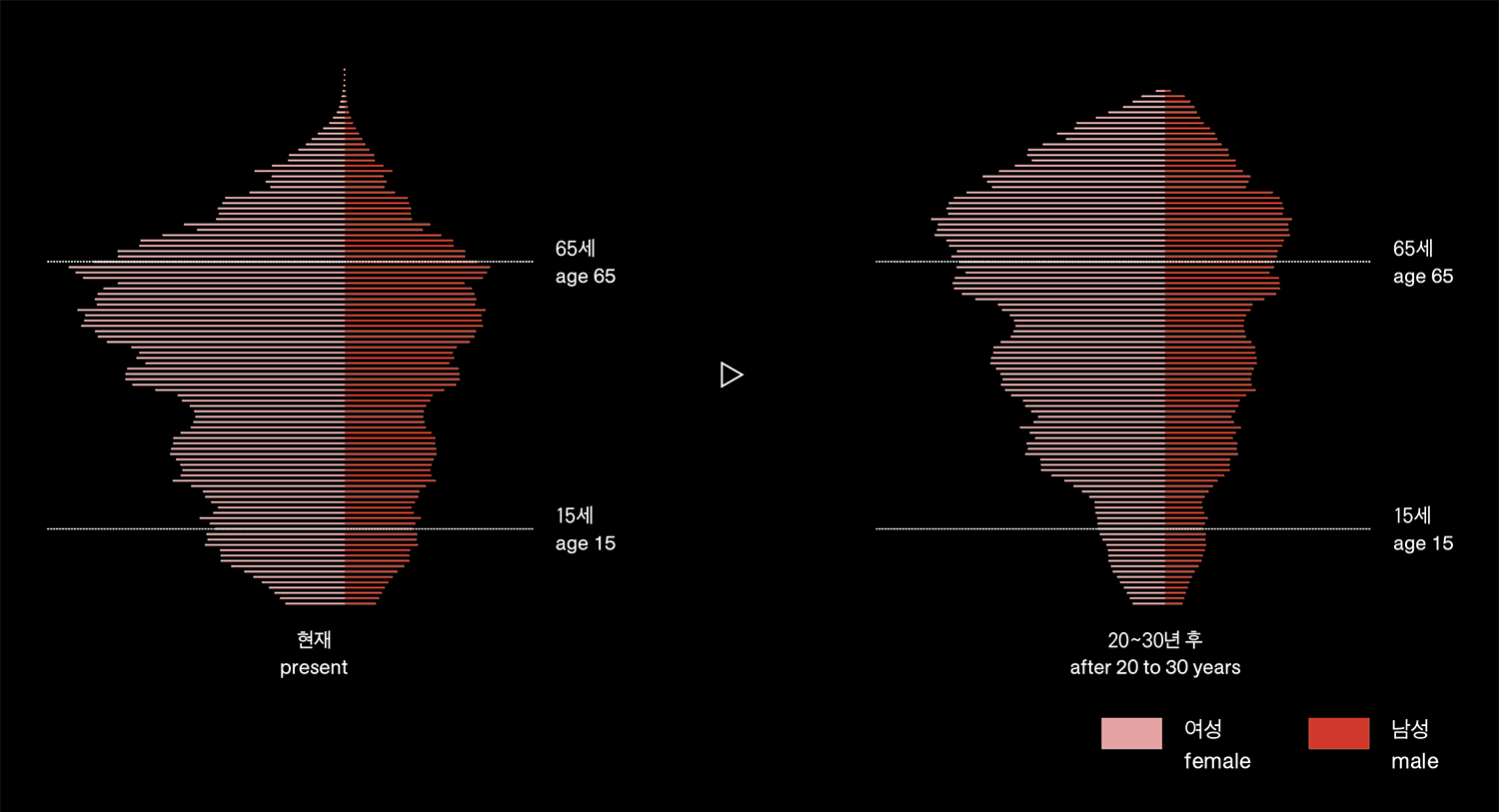

Analysing the statistics, it seems that this population decline will continue in the future. The population outlook for mid-size cities can be gauged by looking at the composition of the city’s population by age group. This is because most cities have a high proportion of their population aged 65 and over. For example, in 1975, only 4.8% of Namwon’s population was 65 and over, compared to 30.6% in 2022. Other mid-size cities have similar proportions of older people. As of 2022, Gimje, Yeongcheon, Mungyeong, Yeongju, Jecheon, Nonsan, Gongju, and Samcheok had 33.4%, 29.6%, 32.7%, 29%, 24.2%, 27.5%, 27.1%, and 26.3% elderly populations, respectively. Most cities exceed the United Nations (UN) standard of 20% elderly populations in ultra-aged societies.

A high proportion of older people in a city may not lead to population decline if the number of births in the town is high and many new people are moving into the city. Therefore, the number of births and population inflow and outflow statistics are essential variables to be considered alongside the phenomenon of population decline.

Firstly, looking at population inflow and outflow statistics, the ratio of outflow to inflow in mid-size cities has been stagnant for the past five years, and in some cities, the outflow rate is higher than the inflow rate. Namwon, Yeongju, Jecheon, Nonsan, Gongju, and Samcheok have relatively high outflow-to-inflow ratios of 1:0.95, 1:0.97, 1:0.98, 1:0.92, 1:0.99, and 1:0.91, respectively, while Gimje, Yeongcheon, and Mungyeong have stagnant, or near stagnant, outflow-to-inflow ratios of 1:1.03, 1:1.02, and 1:1, respectively. In addition, the central outflow of people is primarily young people in their 20s and 30s, who are most economically active.

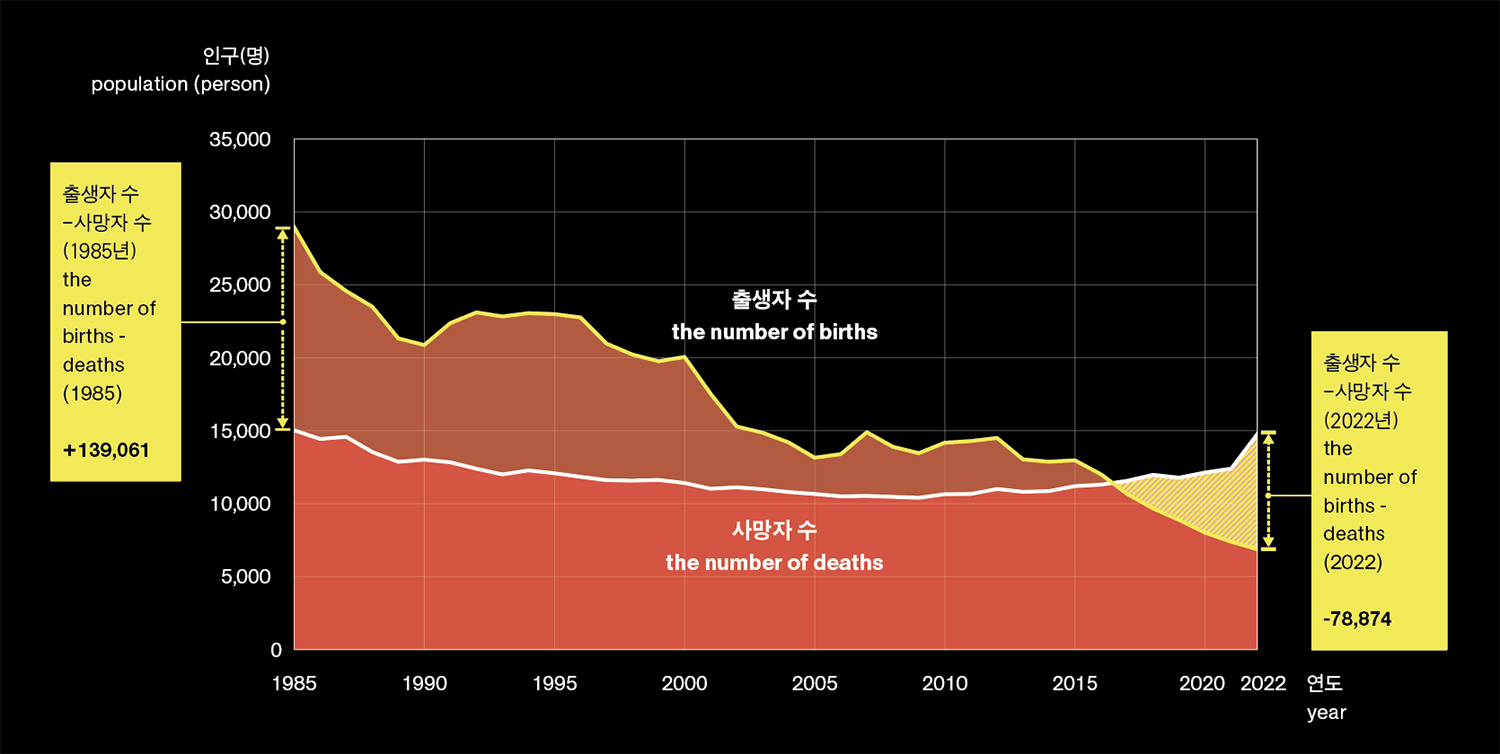

Next, if we look at the number of births statistics, we see that most cities have a low birth rate.

On the other hand, the number of deaths due to ageing continues to rise. For example, the ratio of births to deaths in Namwon in 2022 was 275:1,064, which means that the number of fatalities is about four times higher than the number of births. Other mid-size cities have similar ratios, with Gimje, Yeongcheon, Mungyeong, Yeongju, Jecheon, Nonsan, and Gongju having birth-to-death ratios of 350:1,195; 532:1,407; 266:1,101; 337:1,379; 461:1,353; 402:1,609; and 343:1,356, respectively. If the current ratio of births to deaths continues, the shrinkage of mid-size cities is inevitable. Based on the preceding figures, the population of mid-size cities in 30 years will decline by an additional one-third or more of the current population. If so, about three-quarters of the population as of 1975 would be gone.

Views of empty streetscapes of mid-size cities

Urban Area

While the number of people in mid-size cities has declined, the spatial extent of cities has expanded significantly. Since the 1990s, many mid-size cities have undertaken large-scale new housing developments on their outskirts, which has significantly expanded the area of mid-size cities. For example, until 1975, Namwon had only 9.1km2 of urbanised area. However, in 2023, the urbanised area reached 24.6km2. It is a 2.7-fold increase over the past 50 years. Similar spatial expansion has occurred in other provincial cities. The urbanised areas of Gimje, Yeongcheon, Mungyeong, Yeongju, Jecheon, Nonsan, and Gongju increased by 2.2, 3.6, 2.5, 4.1, 5, 2.8, and 2.1 times, respectively, compared to 1975.

The expansion of spatial coverage is achieved through the following processes. Firstly, apartment complexes are built on the city’s outskirts as new housing development is promoted. During this process, various public and collective facilities, such as courts, city halls, police stations, bus terminals, etc., located in the old city centre will be relocated to the new residential areas. Later, these new residential areas become a new economic centre with programmes related to public and collective facilities including architectural firms, administrative offices, lawyer’s offices, legal offices, land surveyor’s offices, restaurants, banks, etc. These new residential areas attract jobs and capital, leading to a chain reaction of young, economically active people leaving the old city centre.

However, even as the spatial scope of the city expands, and many facilities relocate, not all of them will move to the new economic centre. The traditional market districts and some public facilities remain in the old city centre. As a result, mid-size cities are transformed into a dual urban spatial structure, characterised by the segregation of old and new residential areas. What used to be one economic centre, which previously existed in the old city centre, is now divided into the new residential areas.

Changes in the number of births and deaths outside the metropolitan area (1985 – 2022). While the birth rate is decreasing, the number of deaths due to ageing continues to rise.

Thinning of Concentration

The shift to a dual urban spatial structure disperses a population previously concentrated in a small area over an extended area. This, coupled with a declining population in the city, leads to thinning of population density.

The difference in the thinned population density can be clearly seen by comparing the situation before the 1990s, when the extent of urbanised areas was not significant, with the situation in 2023. In 1975, the population density of the urbanised area in Namwon was 19,888 people per square kilometre, but it dropped to 3,431 people per square kilometre in 2023, a 0.2-fold decrease. This phenomenon is similar in other mid-size cities. The population density of Gimje, Yeongcheon, Mungyeong, Yeongju, Jecheon, Nonsan, and Gongju in 2023 is 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.1, 0.2, 0.2, and 0.3 times lower than in 1975, respectively.

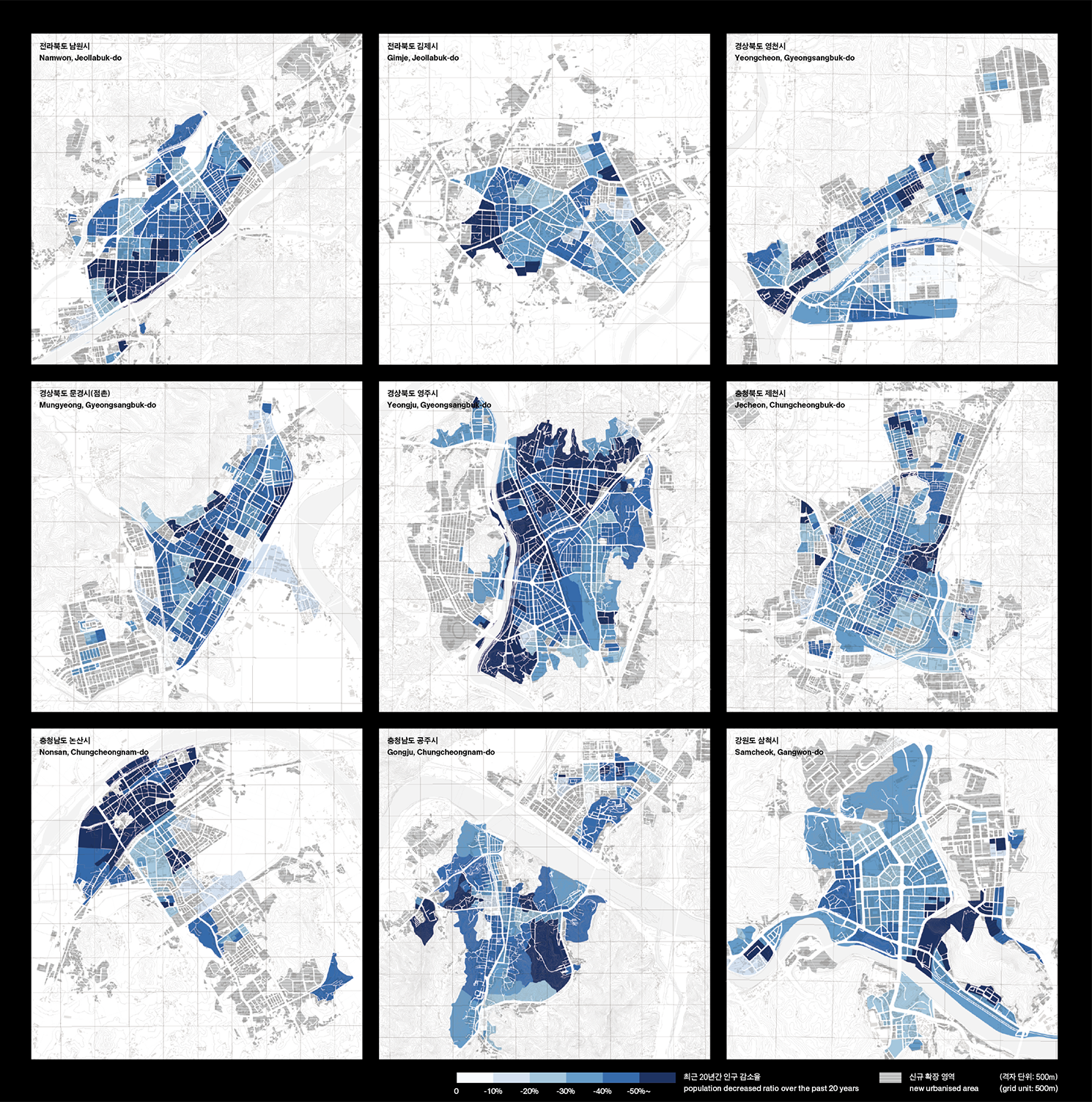

Thinning phenomenon of population density is common in old city centres and new housing development areas. In new housing development areas, the population density decreases as undeveloped areas increase without supporting population growth. In contrast, the population density in the old city centre decreases as the population flows out to new housing development areas.

This city-wide thinning phenomenon, rather than specific neighbourhoods, threatens a certain density level and programmatic cohesion that cities should have. And this is fast becoming the ‘new normal condition’ for mid-size cities due to the demographic changes described above, such as a growing elderly population, fewer births, and lower population inflows.

The thinning phenomenon of mid-size cities over the past 20 years. As population decline and urban area expansion have occurred concurrently, population densities have decreased, leading to the erosion of urbanity.

Weakening Urbanity

The thinning indicates a weakening of urbanity. One can easily experience a weakening of urbanity by walking down the street of a mid-size city. Even during the daytime on weekdays, seeing people on the main streets, both in the old city centre and in the new residential areas, is becoming rarer. If anyone happens to pass by, it is usually older people. However, this phenomenon affects population density and how cities function. It is changing not only the concept of mobility in mid-size cities but also how urban programmes are deployed.

First, let’s look at mobility. Transport in cities is even more critical than in the past due to the dispersal of functions to new residential areas and the expansion of urban areas. However, the status of public transport systems in mid-size cities differs from what it used to be. Until the 1980s, when city areas were small, and populations were concentrated in a small area, city buses in mid-size cities could carry many passengers over a short distance. Now that the city area has expanded and the population has decreased, city buses have to cover a larger area than before. Still, the number of passengers is smaller than before. As a result, the bus operator’s profitability suffers, and the operator is caught in a vicious cycle of limiting the number of bus routes to ensure profitability. Buses are often more than an hour apart in mid-size cities. It is becoming more likely to see routes with only two or three buses daily. As such, public transport systems in mid-size cities are weakening. And it has been replaced by an individualistic, personalised car culture. When one visits a mid-size city, one will experience severe parking shortages in both the old city centre and new residential areas. On-street parking has become a common sight in those cities. Furthermore, the personalised car culture has changed the city from a pedestrian-centred to a vehicle-centred system, making it less common to see people walking on the streets.

Next, let’s look at how the city programme is laid out. New housing development on the city’s outskirts has spread programmes previously concentrated in the old city centre to new housing development areas. As a result, the density of programmes in the old city centre drops significantly. The commercial buildings in old city centre, which used to be filled with programmes on all floors before the new residential areas were developed, now have most of their floors vacant except for the ground floor. In several mid-size cities, where the thinning phenomenon is more severe, even ground-floor shops are not filled with programmes and remain vacant. As a result, the streetscapes along the old city centre are composed of hollow architectural forms without contents.

Residential buildings are different from commercial buildings. The majority of residential buildings in the old city centre are of the detached house type. However, the ownership of detached house type is not a collective one like the apartment type. Therefore, if the owner dies or moves away, the building will likely remain vacant. The empty detached houses have gradually been demolished due to management issues and various complaints. This process ultimately affects the city’s physical form as the number of demolished buildings increases due to an ageing population. It is the gradual decomposition and dismantling of the previous urban form.

These decentralised urban functions, content-free architecture, deconstructed urban forms, and personalised car culture are changing the paradigm of mid-size cities. Mid-size cities are no longer expected to have dense programmes and pedestrianised streetscapes. Instead, decentralised programmes, reduced density, and a personalised, private car-centric lifestyle are becoming the new prerequisites for mid-size cities.

It is important to recognise these changes clearly and harness them in order to intervene in mid-size cities that are shifting towards low development pressure and low-density environments. In other words, acceptance of the thinning phenomenon, the personalised car culture, and the disintegrating urban form must come first. Based on this premise, new types of urban models will need to be explored.

Prediction of change in demographic structure outside the metropolitan area. If the current ratio of births to deaths continues, the shrinkage of mid-size cities is inevitable.

Where We Are Now

The current reality is that while the preconditions for mid-size cities are structurally changing, the strategies for intervening in them are moving in the opposite direction. Look at the various urban revitalisation projects across the country to address declining mid-size cities. Most mid-size city’s revitalisation projects focus on revitalising old towns through street revitalisation schemes. A street revitalisation plan involves selecting specific streets, giving them a theme and colour, and improving the streetscape. The aim is to revitalise the street by selecting specific buildings along it and using them as anchor facilities. However, this is only an effective strategy in cities where a specific density is guaranteed. In conditions of thinning population density, where it is rare to see anyone but older people walking around, such schemes are unlikely to work or, at best, will result in artificially attracting people. It is like a theme park that is deserted during the day on weekdays before it opens and then opens up on the weekend for the out-of-towners who flock to it. Furthermore, such plans are likely to be too preoccupied with a particular narrative, which may fail to account for the unique sense of place, temporality, and materiality of the place. Thus, they are disconnected from the lives of the actual inhabitants, the mode of existence unique to that place.

A different strategy to the previous street revitalisation plan has been discussed recently in relation to urban decline. It is a ‘compact city’ concept influenced by the Japanese shrinking city discourse. In Japan, the concept of a compact city crystallised in 2014 with the ‘Location Normalisation Plan’. This concept of compact city planning seeks to achieve efficiencies by concentrating public, healthcare, and amenities at specific points within the city while institutionally supporting their gradual disappearance in other areas. While such a plan is certainly a compelling concept in the context of a declining population, it is based on the unique urban context of Japan’s mid-size cities and is not compatible with the urban structure of Korean mid-size cities.

Mid-size cities in Japan are prone to earthquakes and other natural disasters, and due to their unique residential culture, most residential areas consist of detached houses. A clear distinction between the centre and periphery of the city also characterises it. The railway station and commercial facilities are located in the city centre, and the residential areas consisting of detached houses are spread out on the periphery, creating an urban structure similar to the urban sprawl of the suburban regions in the United States. In such a city structure, it makes sense to concentrate key functions in the centre, where transport and other infrastructure are already in place, while the periphery gradually dies out. However, the situation is different in Korea. This is because, as mentioned earlier, cities do not have a single centre.

Due to the new housing developments, most mid-size cities in Korea have a dual urban spatial structure with two centres. The two centres are equal in hierarchy, and in some cases, the new residential areas are more dominant. This advantage comes from the type of buildings located in new residential areas. It is because new residential areas are composed of solid and large structures such as high-rise apartment complexes and hypermarkets, making planning for their gradual disappearance difficult. In contrast, detached houses dominate old towns, making it easier to demolish them gradually. As such, mid-size cities in Korea have solid buildings on the outskirts of the city, while the core consists of structures that can be easily demolished. At the same time, railway stations, which are major transport facilities, are primarily located in the old city centre, resulting in an urban structure with an ambiguous relationship between the centre and the periphery, unlike mid-size cities in Japan. This ambiguity in urban structure makes it challenging to apply the Japanese concept of compact city to mid-size cities in Korea. This is because it is difficult to decide where to concentrate urban functions and where to let them dissipate to compress the city spatially.

It has been a long time since we started city revitalisation projects in Korea. Along the way, we have seen time and time again that city regeneration as a way to revitalise declining cities is no longer effective. In addition, the Japanese concept of compact city is not readily applicable to the urban structure in Korea. Now, we need a different approach. We need to acknowledge the process of depopulation and urban decline and find new methodologies within it. A strategy can be found in the gradual demise of mid-size cities, which are becoming less dense. We need to imagine a bricolage-like approach to planning, in which the form and way of life of cities are gradually adjusted by selectively intervening in the situations currently occurring in mid-size cities. This would be active planning in response to the various situations that arise in the process of extinction.

Distribution of public and collective facilities in mid-size cities. Korean mid-size cities are transformed into a dual urban spatial structure, divided into the existing city centre and new urbanised areas due to the new housing developments.