SPACE April 2024 (No. 677)

fala began architectural work in Porto, Portugal amidst the aftermath of the 2011 global economic crisis. To deal with the crisis, cities in Portugal began investing in tourism industry by renovating their old houses, which then led to the boom of Airbnb businesses located at historic centres of Lisbon and Porto. In such a situation where anonymous investors or brokers were beginning to replace the traditional clients, fala in turn discovered an opportunity to develop a new housing type and a unique vocabulary by focusing on architectural elements. About a decade later, fala today has a sizeable collection of 54 completed buildings and the remaining 150 or unbuilt projects. With their irregular layouts of elements such as walls, floors, ceilings, pillars, and windows, fala’s spaces reflect its explorations toward meticulousness and cheerfulness. Let us have a look at fala’s workspace.

House in Rua do Paraíso (2017). A bourgeois 19th century single house was renovated. The back façade features a bold pattern of vertical stripes assembled with white, green and black marble. ©Giulietta Margot

interview Lera Samovich partner, fala × Kim Jia

Kim Jia (Kim): fala made its debut in 2013 with its Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo. I learned that fala’s three co-founders have either studied or worked in various locations such as Japan, Switzerland, and New York. What brought you together to establish this atelier?

Lera Samovich (Samovich): Filipe and Ana Luisa studied together in Porto at the Faculty of Architecture. They met Ahmed while working in Basel, Switzerland, at Harry Gugger Studio. They instantly developed a friendship while discussing OFFICE and Made In projects over lunch. Indeed, they went to Japan to work. Ana Luisa worked at Toyo Ito & Associates (principal, Ito Toyo), Filipe at SANNA (co-principals, Sejima Kazuyo, Nishizawa Ryue) and Ahmed at Atelier Bow-Wow (co-principals, Tsukamoto Yoshiharu, Kaijima Momoyo). But they did not overlap there. Filipe and Ana returned to Porto in 2013 to start an office (although fala’s website was formally launched at the Nakagin Capsule Tower). I joined the office in 2014. Ahmed moved to Porto around the same time. Since then, the four of us have been working together with a small team of collaborators.

Kim: You’ve presented small-scale housing projects that explore variations within the traditional urban context of Porto.

Samovich: We have had several years of working on small-scale houses since 2014. We turned former shops and garages into living rooms, focused on back façades instead of front ones, and worked actively with surfaces and elements of architecture. The context – be it Porto, Lisbon, or, more often, undifferentiated suburbia – was never celebrated but rather challenged. We found margins and possibilities within municipal regulations, allowing for complex volumes, bold patterns, and houses that do not look like houses.

Kim: What elements compose your project narrative? Instead of describing your project as ‘a house for 4 people’, you opt for expressions such as ‘superior kitchens, quirky handrails, light-hearted pavements, masks, proud drainpipes’.

Samovich: When discussing our projects, we often shift the narrative from typologies, functions, and inhabitants to the architectural elements and themes that will be important for the building. Curved walls, suspended columns, doors, and mirrors become the main agents within the space. And in the next couple of years, that narrative will be tested since we are now moving to projects on a bigger scale, to housing rather than houses. It will no longer be about one suspended column but an endless repetition of elements, rooms, and floor plans. Projects will become systems, almost machines. Our main interest is to calibrate that system while maintaining a balance between the standard and the exceptional.

Suspended House (2017). A column levitate a few centimeters from the ground. ©Frederico Martinho

Waves of Glass and Clouds of Metal (2021). A longitudinal axis is framed by two metallic masks.

Interior view of Waves of Glass and Clouds of Metal. Two curved glass brick walls dissociate main and secondary spaces.

Kim: Of the geometrical elements such as straight lines, triangles, squares, and circles, sculptural (and ornamental) elements in pink, blue, and green form fala’s projects. What do these things relate to, and what role do they play in space?

Samovich: These elements often take on a central role within their projects, claiming a degree of independence from the ‘difficult whole’. They adapt and become a different version of the assumed standard. They present moments of tension that resulted from a variety of circumstances – structural necessity, existing columns, mistakes on site – but also symbolic presence and light humour. More often, they have no concerns with function but rather fiction, conceiving spaces that are irrational, surreal, and questioning.

Kim: Aside from the sculptural aspect, your use of materials is also interesting. By using concrete, wood, stone, and glass on architectural elements and furniture, you create a juxtaposition of various materials even in small-scale houses.

Samovich: Our material palette is actually quite basic. We work with local companies and suppliers. For each project, we have to find solutions that respect the given budget, which is usually constrained. It comes to finding the right colours, forms, and types of materials in thick catalogues of samples that are mainly beige and gray, or assembling patterns from conventional stone, wood planks, and panels. Yellow window frames, NCS S 2050-B70G green, or blue shutters emerge from such a quest. And then, each element, or surface, is articulated rather than disguised.

Kim: In many of your projects, ‘a structure that supports nothing’—that is, a non-functional pillar appears repeatedly. It seems like this is one of your ongoing experiments. A pillar is used either as a symbolic sculpture or a small separating wall. How do you interpret pillar as an architectural element?

Samovich: Like any other element, a column has many faces and countless possibilities. Depending on its form and expression, it can adopt different roles and meanings in a project: from a fragile thin metal pole to a chunky concrete column. It can bear structural loads or be suspended from the ceiling, it can be twisted, tilted, or cut off; the variations and potential narratives are endless. Ensuring one is aware of this set of possibilities within one element affects how the project is designed, producing a building that is both fragmented and coherent, rational and, at times, questioning.

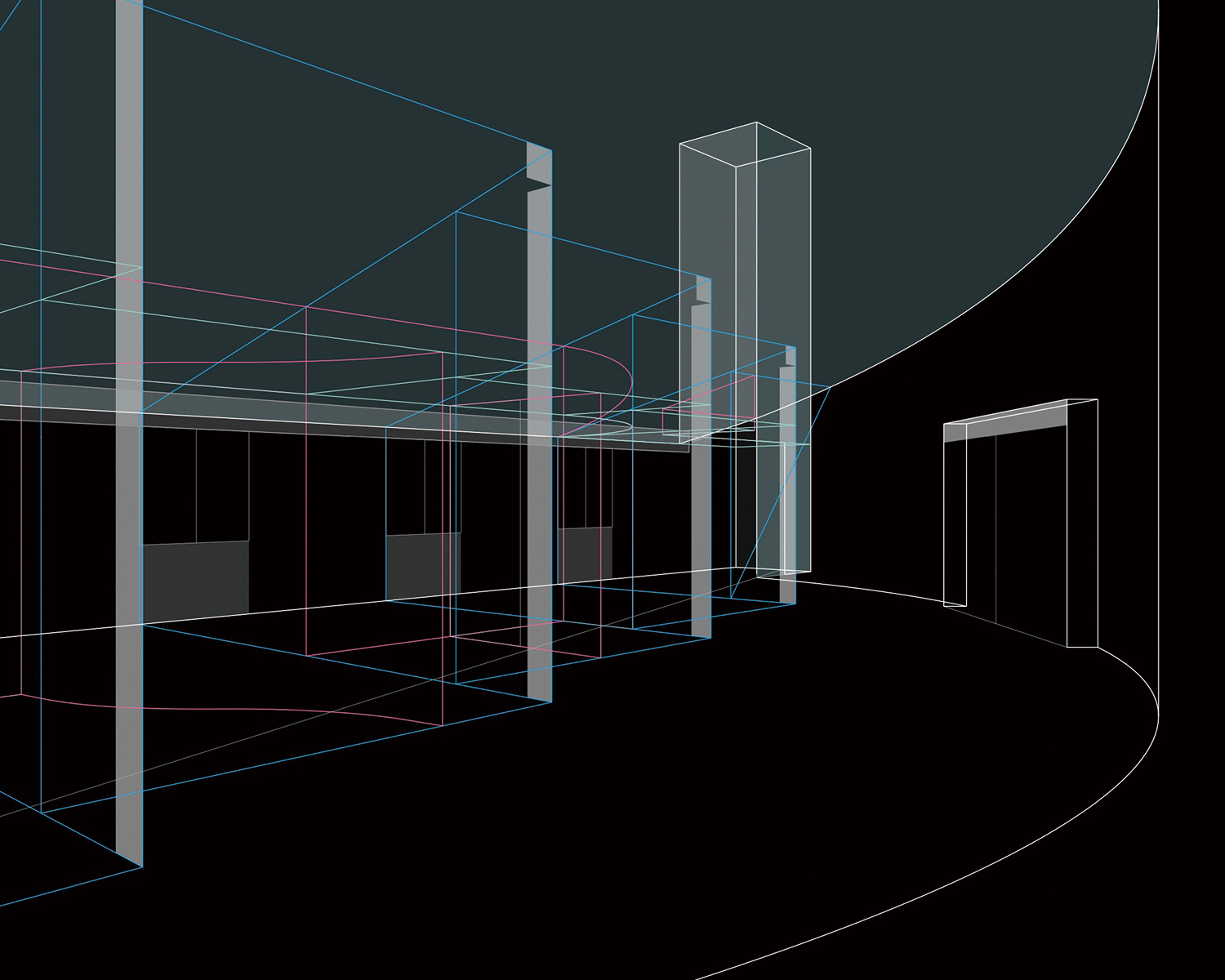

Exterior view and wireframe drawing of House Within Three Gestures (2021). A suburban house on a corner suburban plot in Portugal. The roof is tilted, the perimeter wall is curved, the main division is broken—the house is played out within three gestures.

Kim: The drawings that accompany your work are either used as floor plans or as elements in your collages. At which stage of your project are these collages completed and how do they inform your work?

Samovich: Lately, we have been trying to test collage as a means of architectural production and representation. We are interested in disassembling the image, abandoning the central point perspective, and composing figures that are closer to the idea of the project rather than the rendered view. Collages are produced in series, depicting different sides and spaces of one project. They focus on flat surfaces, the main elements, and present coherent systems of imagery that narrate the project.

Kim: As you were looking back over your work of the past decade, you reflected, ‘We see architecture less as the assembly of buildings than the building of an assembly.’ Can you elaborate what you mean by this exactly?

Samovich: It comes from seeing all our projects as a part of one ongoing exercise that changes over time. We could never pick one project as our most interesting or favourite. They all share bits and pieces of the same themes, elements, and questions.

Kim: What is the joy fala finds in architecture, and in what ways do you think it should be made manifest in your projects?

Samovich: It is the simple joy of ‘doing’ architecture, the shared excitement we experience when working together on a project and contemplating grids, misalignments, and colours starting to make sense on a computer screen. It is the intention to transmit that joy into spaces so that our projects continue exuding that kind of cheerful charisma.

Exterior and interior views of House with an Inverted Roof (2023). An inverted roof brings some necessary quirk into suburbia.

Collage of House with an Inverted Roof

Kim: You recently wrote the introduction to the book In Search of Lost Korean Houses by Suh Jaewon (principal, aoa architects) that analyses and explores eight Korean houses. Despite the foreign architectural environment and urban context, there must have been certain areas that resonated with you considering your work history with houses.

Samovich: Indeed, the book seemed almost familiar because it addressed houses and uncovered narratives and complexities within these seemingly banal briefs. At the same time, it was a fascinating discovery. We had never encountered these names and projects before, and it felt exciting to encounter new variations of the Vanna Venturi House’s staircase or Shinohara Kazuo’s Umbrella House.

Kim: What is your opinion on houses of today?

Samovich: Houses solve the separation between public and private in one way or another. The project is defined by the expression of this boundary. It can be more pronounced or almost dissolved. It can be a curved glass brick wall, or a solid white surface with punched windows. Experimenting with that boundary is an essential exercise that is then key to the special logic behind every project.

Kim: Aside from design work, you also publish and deliver lectures. What significance do these activities have?

Samovich: Lectures, essays, and interviews are fantastic opportunities to organise our thoughts on paper and summarise the past year, two or ten. It is a study of its own that runs parallel with designing projects and following up on construction sites. It deals with the questions of representation and project narratives; it puts different projects side by side, ignoring the physical matter. It allows for comparison and reflection.

Kim: Please let me know about your newest ongoing project. Also, are there any upcoming challenges or experiments that you are currently planning?

Samovich: We are currently working on two competition projects that we won; both are collective housing projects. It is a jump in scale for us and the new reality in dealing with public commissions. It presented new chapters in our working life. We are now working with repetitive and systematic projects. There is not much room for experimentation, since it is highly regulated. So, we have to rediscover the joy within a new set of parameters and constraints and find room for imperfections or eccentricities within rigid systems.

Houses of Cards (2020). The two-storey buliding concealing five houses.

Construction view of House of Three Structures (2021 – ongoing)