SPACE March 2024 (No. 676)

I AM AN ARCHITECT

‘I am an Architect’ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

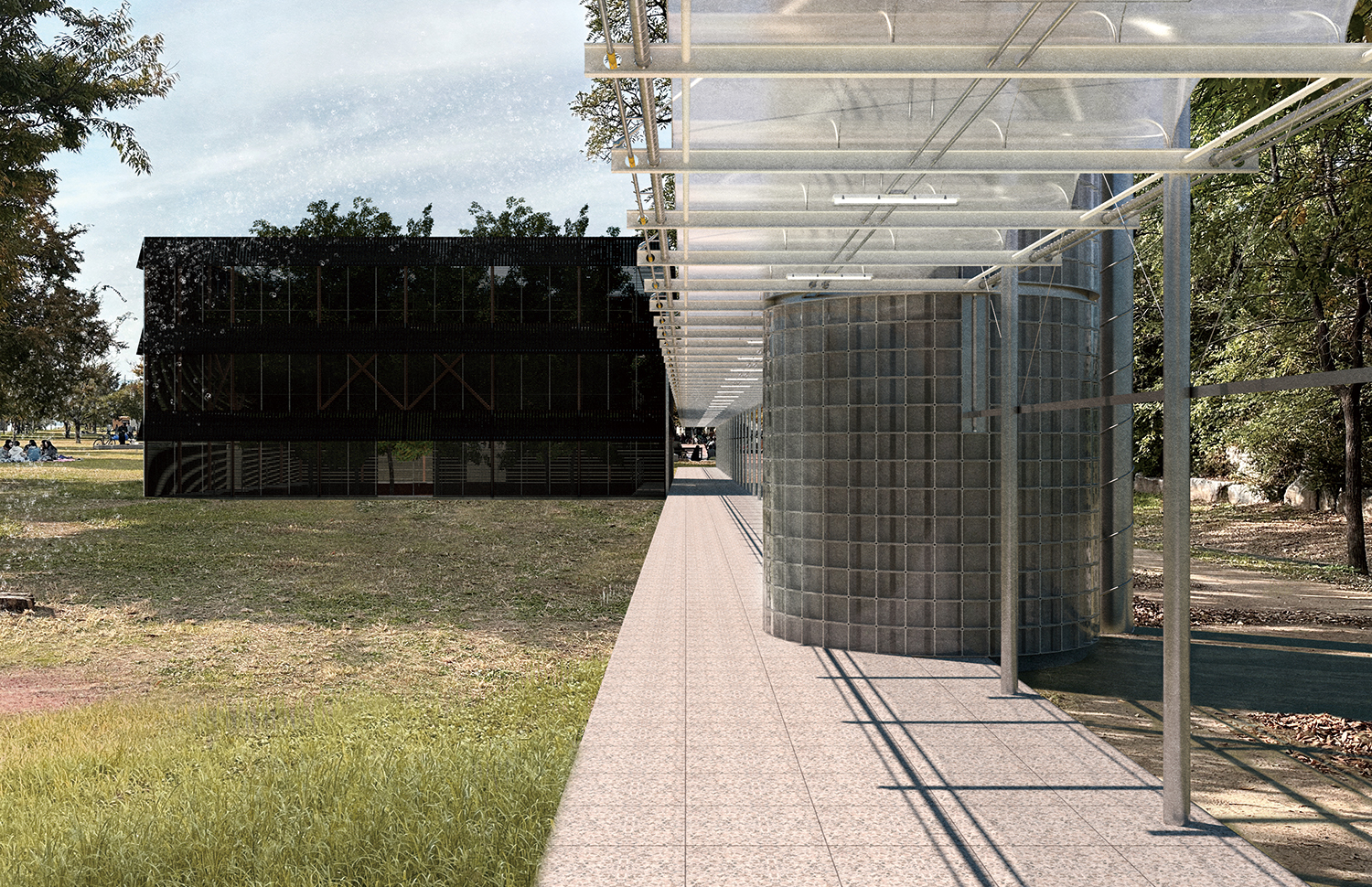

Rendering image of Manuscript for nature (2023) ©architectural/practice

interview Heo Sungbum principal, architectural/practice × Kim Jia

Starting Simply

Kim Jia (Kim): You completed your undergraduate studies in Korea and went to Switzerland for student exchange programme and work experience. Was there a particular reason for choosing Switzerland?

Heo Sungbum (Heo): At that time, rather than having a deep admiration of Swiss architecture, I just had a young desire to go abroad and challenge myself. I even got on a plane saying I would learn how to make cheese. It was a time when I was more interested in the world than architecture, so it seems like it was more of a vague choice than a clear vision.

Kim: I think it’s those choices that make up one’s life. What did you see and feel during your stay in Switzerland?

Heo: In the beginning, I stayed in Lucerne for a year as an exchange student. The first semester went relatively smoothly as I took classes in English, but the second semester was a challenge because the design class was only offered in German. (laugh) Being unable to speak German, I went to class for a week and thought it wasn’t for me. So, I promptly dropped the course, packed my books and a tent, and went on a bicycle trip to Graubünden, a region in the Alps. There, I visited architectural works by Peter Zumthor, Valerio Olgiati, and Gion Caminada. It was interesting to see how even in small towns diverse architecture stood out. Experiencing unique and intricate architectural works even in provincial areas was eye-opening to me. Perhaps what I saw and felt back then might be the reason I’ve been practicing architecture up to now.

Kim: You have work experience in architectural firms in Zürich, London, and Seoul. What kind of projects did you mainly work on?

Heo: After completing my student exchange programme, I stayed in Switzerland for an additional year, working as an intern in Zürich. At the time, without a degree and as a foreigner, I mainly assisted in various projects. Upon returning to Korea, I started working at JK-AR. I worked on the House of Three Trees (2018, covered in SPACE No. 620), a detached house project located in Sangju-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do. I was involved in the construction process for several months at the site and had an intensive experience of watching the building process. Afterwards, I went to the U.K. on a working holiday and worked at the Mcmullan Studio in London, primarily focusing on design competition-based projects. I worked on various projects from installation to urban planning.

Architectural Architecture

Kim: You returned to Korea around 2020 and founded your own Seoul-based architectural/practice. What made you decide to go independent?

Heo: I moved back to Switzerland from the U.K. and was working at Comte/Meuwly, but the COVID-19 pandemic forced me to return to Korea earlier than planned. Before I came back to Korea, I participated in the DDP Open Curating 2020. Winning the competition naturally led me to start my own firm, architectural/practice.

Kim: Tell us the story behind the name of your office. Why did you name it architectural/practice?

Heo: The adjective ‘architectural’ is versatile enough to be used in other fields like art or fashion. It encompasses not only proportion, composition, or constructive perspectives but also multi-dimensional aspects such as space, environment, history, philosophy, and art.

I believed that the organic nature inherent in the term ‘architectural’ could also influence architecture itself. I incorporated the desire to pursue ‘architectural’ architecture into the name of my firm. However, it does not necessarily have to have a fixed meaning. In the U.K., ‘architectural practice’ is a term often found in office profiles, similar to the way that Korean firms commonly use the term ‘architectural design firm’. I work with the hope that such general terms can take on specific meanings in Korea.

Kim: In the profile of architectural/practice, there are some keywords mentioned: architecture, research, education, urbanism, and natural environment. What kind of activities do you engage in?

Heo: Like any other office, I continue to participate in public competitions and design work. At the same time, I teach expression classes that deal with media, and design studio classes in Soongsil University and Kaywon University of Art and Design. Research is the backbone running through almost all my works, and it informs what I upload on Instagram. I strive to capture arbitrary objects or situations created in urban environments through photography and endeavour to translate them into drawings or other media. Both urban and natural environments have been the starting points for most of my projects so far.

Redefining Nature

Kim: You participated in DDP Open Curating 2020, Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2021 and Seoul MARU Public Intervention 2023, presenting works from an urban perspective.

Heo: For the DDP Open Curating 2020, I curated and participated in the exhibition ‘Apartopia: House of the Future’. It focused on the emergence of new forms, spaces, and cultures in cities with a high concentration of homogenised housing types such as apartments. I tried to imagine the future of Seoul through elements such as storage, beds, toilets, sinks, and exercise equipment. At the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2021, I presented Balcony is a new garden, which aimed to rethink the relationship between the city and nature by focusing on the phenomenon where balconies in large city environments like Seoul function as urban gardens. ‘Our Place in Breeze’ (covered in SPACE No. 670), which was selected as the finalist in the Seoul MARU Public Intervention 2023, was to enhance the outdoor space of Seoul MARU, a public space in the city, by planting laurels and artificial flowers for citizens to experience natural elements such as wind within it.

Kim: Nature has always been a topic in your work. How do you see the relationship between architecture and nature?

Heo: I believe architecture and nature exist in interaction with one another, rather than in opposition to each other. I do not agree with the dichotomous urban view that separates cities from nature.

I am interested in redefining the concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘natural’, now that the conceptual distinction between artificial and nature is blurred and the city, the largest artifact, has become an environment beyond culture. For example, parks were once ethical spaces that emerged in response to the industrialisation of cities. Nowadays, the proportion of parks has been legislated from an urban planning perspective, such as the proportion of landscaping according to the area and public space. Parks can be seen as a concept that is subordinate to the city. However, just as the image of space changes when the social and cultural environment changes, I think that as the environment is a contemporary topic, parks should be explored as another ‘environment’ beyond the existing image of the reproduction of nature or a space subordinate to the city.

Kim: Manuscript for nature (2023) is a design that was submitted to the Ttukseom Idle Pier Landscape Improvement Design Competition. How did you interpret the urban parks of Seoul?

Heo: I started with the question of what kind of spatial image a park should pursue if it is to be a space that is not dependent on cities. The area around Ttukseom was initially a recreational space such as a hunting ground for kings of the Joseon Dynasty due to its beautiful scenery, and then was urbanised in the 1930s as the Ttukseom Park. Undergoing urbanisation in the 1980s, it became an urban park, as it is now. There was bridge built apparently at random in this process, and I thought there was no reason for it to remain, so I proposed a public space based on its gradual deconstruction. Giving it a structural role to support the newly added solar panels and sprinkler system while maintaining the unique function of the existing piers as foundational structures, I abstracted the giant cylindrical piers and arranged metal cylinders at different scales in a radial pattern, cladding the massive pier structures with glass blocks. In the centre, six willow trees were intended to form a forest, so the piers were designed in relation to this feature. In other words, I aimed to redefine the idle piers as infrastructure for the environment rather than the city. Through this approach, I proposed a park with distinct characteristics from conventional parks, focusing on the restoration of natural spaces rather than the reproduction of nature.

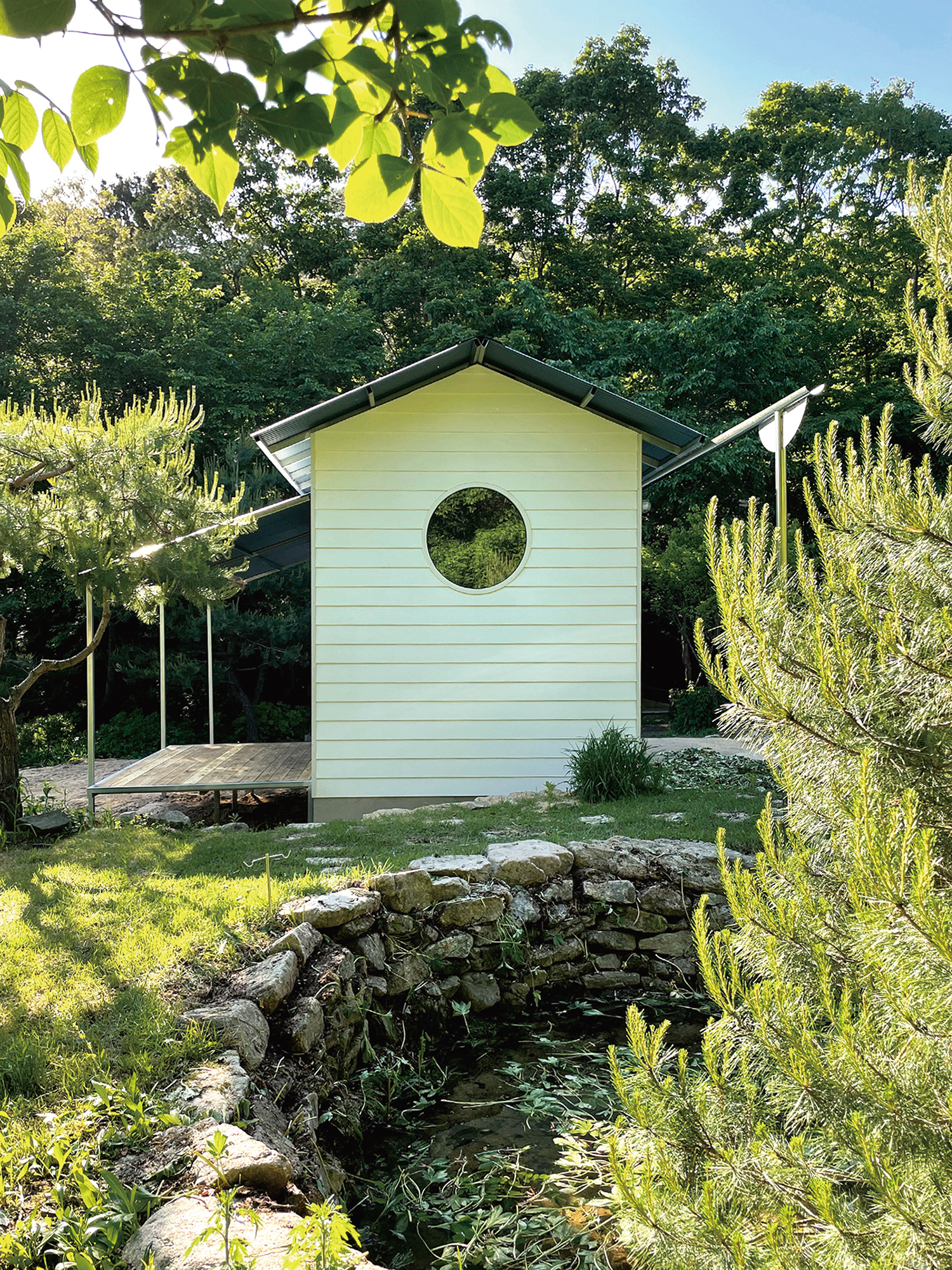

Gartenhaus (2021) ©architectural/practice

Between Concept and Construction

Kim: You have been proposing ideas mainly through open competitions, and in the case of the completed project Gartenhaus (2021), it has led to construction as well.

Heo: Gartenhaus is a weekend house built in Hongcheon. Situated at the edge of the village, along the road that leads to the mountains, it lies on the boundary between nature and artificial environments. The building is ultimately a traditional farmhouse. While it is typologically universal in that it looks like a farmhouse, it is specific in that it has a scale that is hard to find within this type. Traditional farmhouses are typically built as mobile homes and are subject to height restrictions set by transportation laws, with a maximum height of 4m. However, due to the difficulty of access for trucks at the site located at the edge of the village, construction was conducted on-site. Considering the limited construction budget and maximising efficiency in the context of mobile home typology, I focused on the point where I could stay within the type and still respond to the environment. Since the farmhouse, if not a mobile home, is only limited in area, but not in height, we thought about how to respond to the environment through scale and selected a height of 4.5m. I also tried a variation on the staircase that goes up from the ground to a farmhouse, which becomes wider as you go up, conceptually and physically expressing that the outside environment becomes smaller as you enter the house. There was an existing artificial pond on the site, and I extended the eaves of the farmhouse roof to connect with the pond. This transformed the artificial pond from merely an aesthetic landscape to an environmental element that functions in conjunction with the architecture, moving beyond the concept of dependent spaces. I tried to realise a more organic architecture.

Kim: It’s interesting to see the intersection where concepts and construction intertwine in various projects.

Heo: In general, it would be natural for construction logics to follow conceptualisation. However, regarding the architectural environment in Korea, there seems to be a clear phenomenon of reversal where conceptual ideas emerge from the process of considering construction. Gartenhaus is such an example.

Rendering image of Our Place in Breeze (2023) ©architectural/practice / Background image courtesy of JUNLEEPHOTOS

Practicing and Realising

Kim: Among your ongoing activities, is there any specific area that you particularly want to focus on?

Heo: I’m planning to focus more on my role as an educator. Particularly, this year, I’m preparing to run a lecture series, as I will be leading studio classes, where I will share the entire process from topic selection to final outcomes. Additionally, starting this year, I will be continuing my work on architecture as a part of art, since I’m affiliated with Jamunbak Art Residency. I also maintain a consistent interest in theoretical areas such as publication and criticism. In April, I’m preparing for an exhibition at Royal X in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi-do.

Kim: I look forward to the trajectory of the architectural/practice.

Heo: I aim to enhance my ability to integrate the entire project, and I believe that such skills are best learned through the experience of actually constructing buildings. Therefore, when I work on a commissioned project, I try my hardest to bring the best results, regardless of the scale and conditions. If the budget is limited, I work within that budget, and if design freedom is restricted, I try to incorporate ideas even in small aspects. Just as with the name architectural/practice, architecture is in the process of practicing and realising. In that sense, for me, teaching, exhibitions, texts, and images are all architecture. As Hans Hollein said, everything is architecture.

Heo Sungbum our interviewee, wants to be shared some stories from Seo Junhyuk, Choi Sejin (co-principals, mhgh architects) in April 2024 issue.

Rendering image of Manuscript for nature ©architectural/practice