BCHO Partners, the second collection of works by architect Cho Byoungsoo is scheduled to be published by SPACE BOOKS in January 2024. By considering architecture as a dialogue with the earth, his work embodies a profound respect for the characteristics and essence of the earth. Earth, platform, screen, and mass are the fundamental elements interwoven throughout his diverse body of work spanning over the past 30 years. Each of these four approaches to interpreting the land explores how architecture emerges from the ground, traverses it, permeates it, and shapes it. In an interview with the author, SPACE delves into the various aspects of the book that led to its compilation, the perspectives that illuminate his projects, and the profound meaning embedded within the key drawings.

interview Cho Byoungsoo principal, BCHO Partners × Park Semi

Cover image of BCHO Partners

Park Semi (Park): This is the second collection of works, about 15 years after the first collection, Cho Byoungsoo (2009), published by SPACE. It’s the second book in the same format, so I wonder what it means to you?

Cho Byoungsoo (Cho): After studying architecture in the United States, I returned to Korea and established a practice in 1994. If the first book was released 15 years after I began practicing in Korea, the second book is now being published approximately 15 years later. In the first collection, my emphasis was on the process of developing each project. I approached my work with an attitude of observing things as they are, rather than adhering to a particular theory. From that perspective, my intention was to share the narrative of what I admired and what I created. The second book, however, takes on a more retrospective tone, reflecting on my body of work. Next year marks the 30th anniversary of my architectural endeavours in Korea, and I felt it was an opportune time to organise and reflect. Upon reviewing my work, I noticed a discernible trajectory, and one of the central themes that emerged was the concept of earth. This book, therefore, places a particular focus on the contextual relationship between my architectural work and the earth. While I am cautious about being confined to a rigid vocabulary when developing a project, I believe it holds significance to contemplate the attention we have given to the earth and the region.

Park: I want to hear about the earth. What does it mean to you in your work?

Cho: During my years of studying architecture in the 1970s and 1980s, the prevailing focus was on emphasising programmatic aspects rather than paying attention to the earth. The primary goal was to create architecture that faithfully served the intended purpose. However, as I gained practical experience, I came to recognise the challenging and crucial nature of the relationship between the earth and the building. My initial projects in Korea were situated in hilly areas like Seongbuk-dong and Pyeongchang-dong, often involving the use of elevated artificially constructed platforms. Inevitably, I found myself contemplating the earth and its significance. As my architectural journey progressed, my exploration naturally led me to discover the intrinsic beauty of Korea. I pondered whether we possess the inclination to seek a sense of naturalness by responding to the earth, rather than striving for refined forms achieved through meticulous construction. This quest can be described as the beauty of mahk or Korean naturalness. Upon reflecting on my body of work, I can discern a consistent effort to unearth something profound within the earth.

Park: The book illuminates the project with four keywords: earth, platform, screen, and mass. How were these keywords arrived at?

Cho: While the first book presented projects in a listing format rather than organising them conceptually, in this book, my intention was to shed light on them through a more flexible framework. The four keywords do not exist in isolation; they often exhibit interconnected relationships, at times sharing similarities, and at other times bearing contrasting meanings. Ultimately, they all converge upon the concept of earth, which I have categorised into four distinct vocabularies based on their respective relationships with the earth.

Park: Can you briefly describe the four concepts?

Cho: Taking a broad perspective on the earth, it can be understood as a concept that encompasses elements such as light, wind, and plants. In the case of Korea, the appearance of the earth undergoes transformations with each of the four seasons. The terrain is characterised by slopes, and even within Seoul alone, one can observe an abundance of mountains and hills. These inherent characteristics of the earth find their reflection in architecture. A platform, as a raised surface, represents a second ground and plays a significant role. Notable examples include the Mandae-ru of Byungsan Seowon or Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. The platform creates a relationship where one stands at a certain vantage point, looking down. In Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, nature flows beneath the elevated platform. This aspect holds great importance in western modern architecture and has also received attention in traditional Korean architecture. Platforms serve as a means to organise architectural forms and spatial flows based on the relationship with the earth, offering infinite possibilities depending on the earth’s characteristics. The screen is closely connected to the surrounding context. It serves to address situations where the surroundings may be chaotic or when a form needs to accommodate multiple functions. Screens can manifest in various materials and functions, tailored to the specific site requirements. They range from providing privacy to allowing light to filter through while blocking wind. Mass, on the other hand, is emphasised as a solid entity firmly rooted and anchored in the ground. The mass itself is not the primary focus, but rather how it interprets its relationship with the land. For instance, in the case of A by Bom (2021), the generous 4.5m opening enables the street view to penetrate the building. Additionally, seven windows facing the street capture the surrounding environment, distant sky, and landscape. Although the building is surrounded by structures that reveal their own functions and forms in the context of Cheongdam-dong, Gangnam, the massing was carefully designed with the consideration of passerby in mind.

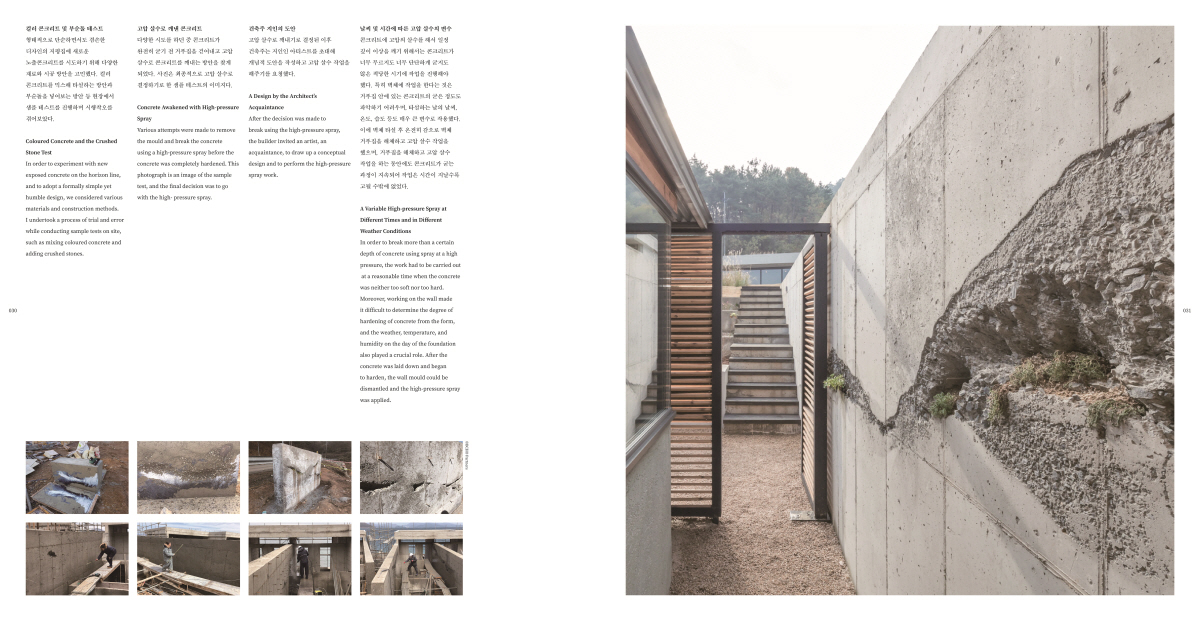

BCHO Partners focuses on construction and detailed drawings.

Park: Another feature of the book is the emphasis on construction and detailed drawings. You’ve been known to experiment with materials with a focus on construction and detailing; what does this mean for BCHO Partners?

Cho: It may be attributed to personal preference or a particular working style, but I have always maintained an attitude of observing things as they are. This aligns with the Epigraphy school’s perspective, which considers the inscriptions on stone as the sole object of study. It differs from the approach of interpreting stone carvings by paraphrasing them based on the absence of one or two characters. Similarly, Chusa Kim Jung-hee also held great respect for the tangible and the real. A notable example of this is Sehando, a cursive painting that exemplifies such values. In Studies in Tectonic Culture (2001), the architectural historian Kenneth Frampton explores how tectonics manifest themselves in different cultures. In the western context, we employ cement or mortar to construct with stones, whereas in Korea, we rely on the simple act of stacking stones upon stones. If we observe the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress, we can appreciate its unique beauty. It is from this perspective that when I engage in architectural work, I actively consider not only the form but also the selection of materials and construction techniques. In an era that increasingly loses touch with materiality, I firmly believe that the essence resides in embracing the phenomenon as it presents itself. The pursuit of correct and genuine architecture lies precisely at that juncture. This is why we emphasise construction and materials, as they are the very processes that constitute architecture.

Park: Among architects, you have published a lot of books in various ways. I’m curious about your views on the medium of books.

Cho: My first book primarily focused on documenting my work, while the second collection aimed to organise the existing projects in a more reader-friendly manner. For instance, in the case of a book, which was published by an Australian publisher, I directly commissioned the book with the intention of preserving the unbuilt projects that were gradually fading away, even within the internal documents of my office. Another publication titled Byoung Cho: My Life as an Architect in Seoul (2023) is a collection of essays that delves into the city of Seoul from the perspective of an architect who grew up in the city and explores the journey that led me to practice architecture. Throughout my publications, the emphasis has always been more on documenting my work rather than declaring a specific architectural direction or aim.

Park: What is the significance of this book among the many books that have been published? It is a book that shows the journey of BCHO Partners.

Cho: Even if the work published is merely a record, there are instances where it takes on new significance when presented as a whole. Personally, I believe it unveils the type of architecture I have been striving for within and between my projects. With over 40 projects documented between the first book and the present one, it represents a substantial body of work. I sincerely hope that readers will be able to interpret the projects through their own unique perspectives. Of particular significance is an essay contributed by Pai Hyungmin (professor, Univesity of Seoul), who has observed and provided critique on my works. His essay adds a macro-level perspective to the collection, enriching the subjective record with valuable insights. Furthermore, during the process of compiling this book, I discovered a connection between my architectural work and my writing endeavours. Exploring themes of earth and mahk through writing has provided me with an opportunity to organise my thoughts, especially as I prepare for the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism.

Park: As the general director of the 4th Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, the theme of the event was ‘Land Architecture, Land Urbanism’. I imagine it was an opportunity for you to express your thoughts on the concept of earth.

Cho: Indeed, the concept of earth encompasses various semantic systems. While the earth covered in the book refers to ‘earth’, the focus of the biennale was on ‘land’. Specifically, we emphasised the significance of ‘land’ as a platform, rather than solely considering the physical properties of the soil that constitutes the land. When we discuss ‘landscape’, we inherently incorporate the idea of ‘land’. From the perspective of the city’s master plan, the aim was to acknowledge the substantial loss of land in Seoul and explore practical ways to overcome this challenge.

Park: The first book came out 15 years after the establishment of your practice, and now the second book after another 15 years. How do you envision the next 15 years, the third phase?

Cho: Currently, I am engaged in a project located in Buan-gun, Jeollabuk-do, which is not included in this book. It involves the revitalisation of abandoned warehouses and unoccupied houses—a truly fascinating and meaningful project. Moving forward, I aspire to continue seeking significance and answers with interest and responsibility in small things that are just as important as large-scale or public projects.