SPACE February 2024 (No. 675)

Sculpture with a large triangular mass floating above the ground. The wide surface of the gabled roof is clad with natural slate, which is easy to maintain in Jeju’s climate. (Trimmen, 2022)

The roof mixed triangular and parabolic lines. (Surico, 2020)

The Solution as Revelation

Architecture is ultimately all about revelation, and architects are inevitably aware of this meaning. Whether superficially or internally, physically or ideologically, architecture is bound to be disclosed in a certain way. Blurring a presence is a method of ‘faintly revealing’. Architecture that does not reveal itself is like a machine that does not operate. It is by revealing itself that architecture relates to society, and it is in this relationship that the meaning of architecture is formed. An architecture that is not recognised by society is a dead architecture. For us, the meaning of the revelation is about determining the direction of architecture, solving issues, and questioning how architecture can relate to society. The solutions are diverse and involve multiple interactions. Placing architecture on the border between the non-daily and the daily, creating a physical order of representation, and mediating between simplicity and complexity: these are all solutions as revelation.

Near Gotjawal, we conceived of a sculpture in which boulders of volcanic rock would be placed on a flat plate. (Chungsu Got, 2023)

Spaces Realised Through Form

Form, which determines the substance of architecture, is usually perceived as the rational outcome of the architect’s thinking, concepts, and conditions. However, inversely, the form can also be a starting point that triggers architectural thinking. Just as the body of an insect is divided into head, thorax and abdomen, the form of architecture is composed of roof, walls, columns, floors, foundations and so on. If the merging of an insect’s head and thorax is called a mutation, then the merging of a roof and wall is a variant rather than a mutation. By breaking with conventional thinking, such variants provide users with more diverse and new spatial experiences. Many experience the power of space in buildings which deviate from perfect square forms. The very sense of freedom that people feel in an interior space at that moment amplifies the sense of the essential qualities of an architectural space. Forms clearly project purpose and guide the character of a space. As in the cases of the triangular space (Trimmen, 2022), the space as if an oreum has been placed (Samdal Oreum, 2019), and the space that appears to be formed of lumps of stone (Chungsu Got, 2023), the overall sense of architecture forms colourful variations when a strong sense of plasticity on the exterior leads into the interior space. Of course, we cannot rest our understanding of good architecture on a sense of presence or the uniqueness of structural forms alone. However, this does not mean that the essence of architecture is blurred when we prioritise form. Perhaps our work is an unintentional but ironic step towards phenomenological architecture, which has provoked countless thoughts.

The rear side open to the landscape with ocean view. (Trimmen)

A stay space in which one enters the room (on the second floor) through the bathroom (on the first floor). (The Stair, 2019)

Baked bamboo has good resistance to corrosion and can be easily cut out, making it ideal for surfaces that require free curves or voids. (Walden House, 2020)

Consistent Uniqueness

Uniqueness means something special that deviates from the usual rules or principles. In architecture, the unique is used to make things look unfamiliar or to loosen boundaries. These creative attempts have become consistent as we are repeated and developed across our projects. Our work with space at its focus has maintained and developed a consistent sense of uniqueness. This attitude is reflected in our approach to context, function, structure and materials. Through countless attempts to create more free spaces and forms than before, such as curves and surfaces that bend in two or three dimensions, we have accumulated sufficient know-how and detail to have made the selection of materials (baked bamboo, zinc, natural slate, brick, etc.) as well as their cutting and joining to suit the climate and environment. Consistent uniqueness is only created when data is collected and accumulated. From a single root, the vocabulary of architecture grows variations according to the situation and makes itself manifest in different ways within projects. These spaces are imbued with emotions and inspirations that cannot be explained by objectivity or rationality alone. This is perhaps the most consistently uniqueness of our architecture.

Baked bamboo (9.9m in standard size) cut into thirds, which is 3.3m long, was set as the height of a single floor and used to finish the entire curved surface of the building. (Heunghaerang, 2023)

Ondumak is a reinterpretation of a wondumak (traditional Korean cottage). A common lookout shed in tangerine fields, into a pavilion shaped like an elevated observatory. (Uigwisodam, 2021)

An interior space with no doors and only compelling psychological compartments. (Trimmen)

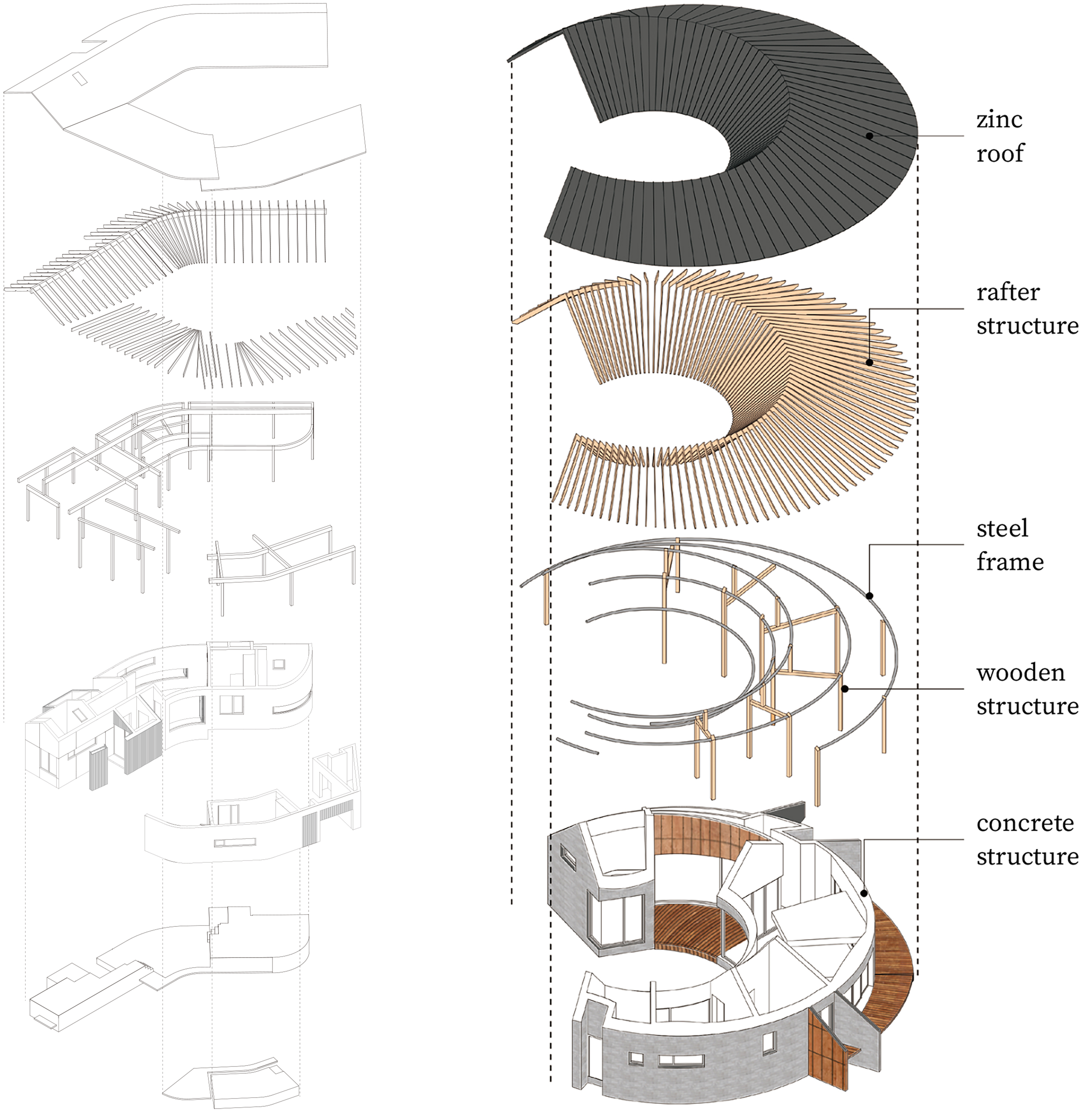

(left) A mixture of light wooden structure and heavy wooden structure. To realise the curved gable roof, zinc, a common roofing material, was used and cut out without any loss of material. (Jian’s House, 2018), (middle) To realise the curved, three-dimensional sloping roof, a hybrid structure was employed, mixing three kinds of structure, namely wooden structure, steel frame, and reinforced concrete. (Samdal Oreum, 2019), (right) The coexistence of triangular and parabolic roofs that convey different formal messages. (Yeongpyeongdong House & Cafe, 2023)

Transforming of Non-Quotidian

It was in the early days of the office when we were converting a 200-year-old stone house in Jeju into a stay (TORI cottage × KarreKlint, 2016). There was a rumour in the neighbourhood that we were ‘repairing this dilapidated, rotten, old stone house’, and residents came by every day to tell us their stories of the house. They always told us: ‘Why repair it when you can just tear it down and build a new one?’ But once it was open as a stay, it became a local attraction for people from other regions. Throughout this project, we achieved a shift in perspective, wherein the ordinary lives of Jeju people were transformed into exceptional and non-quotidian spaces through the eyes of others (mainlanders) who were used to enjoying a very different time and space. In architecture, new experiences are not limited to formal interventins; many possibilities open up when we expand our inertial thinking to that of the eyes of others. Since then, we deliberately try to approach our work from a non-daily perspective when we start a project, and we also try to twist our previous non-daily perspectives to look at thigs from an unfamiliar point of view. The process of projecting a sense of the ‘non-quotidianʼ into architecture, such as changing the use of a space or reversing the hierarchy or order of a fixed space, has led us to constantly objectify ourselves and become conscious of the gaze of others. Perhaps this change of perspective could be a solution to the challenges facing contemporary architecture, which can only be that a fixed substance in a rapidly changing society and culture must respond in increasingly agile ways.

(left) Structure diagram (Jian’s House, 2018), (right) Structure diagram (Samdal Oreum, 2019)

Obsession with Trials

Our architecture is not so much a grand challenge, but a try close to an obsession. This explains the stubborn journey and attitude of accumulating our own architectural vocabulary to realise unique forms and spaces. The process of practising architecture is like a journey in search of buried treasure. It’s a daunting task, but we have to have a variety of strategies and contingency plans to overcome the difficulties. The trusted map (architectural drawings) in our hands is not enough to cope with the variables and risks we will encounter on site. We have been able to continue our exploration because we have accumulated solutions that border on ‘over-design’ to push at the limits of reality, such as time and cost. At the end of the journey, when architects, clients and users discover and enjoy the treasures together, it will have been a worthwhile endeavour.

Bricks were cut three times to create a curved surface to reduce construction costs. (Samdal Oreum)

A unique structure in which a single-family house and a café share an inner courtyard. (Yeongpyeongdong House & Cafe)