SPACE January 2024 (No. 674)

Is there any other building type in which an architect’s will is as difficult to express as in the case of neighbourhood living facilities? If we continue to satisfy the logic of economic and legal conditions in our profit-oriented cities, there will not be much room left for an architect to lead the way. At the same time, it is a type of building that is unavoidable because it is a dominant building mode that fills our everyday lives and shapes our streetscapes. In earlier works such as Patema Inverted (covered in SPACE No. 626) and Dongtan Janus (covered in SPACE No. 651), Kim Dongjin + L’EAU design have explored neighbourhood living facilities that respond to the diverse context of the city. Here, we present Imun, Sinsa, and Sangsoo, a series of works that use the combination method of architectural laminating codes known as ‘Triplet Code’. Yim Dongwoo (professor, Hongik University) analyses these three projects to find new architectural potential in the prevailing and emergent logics of the neighbourhood living facility.

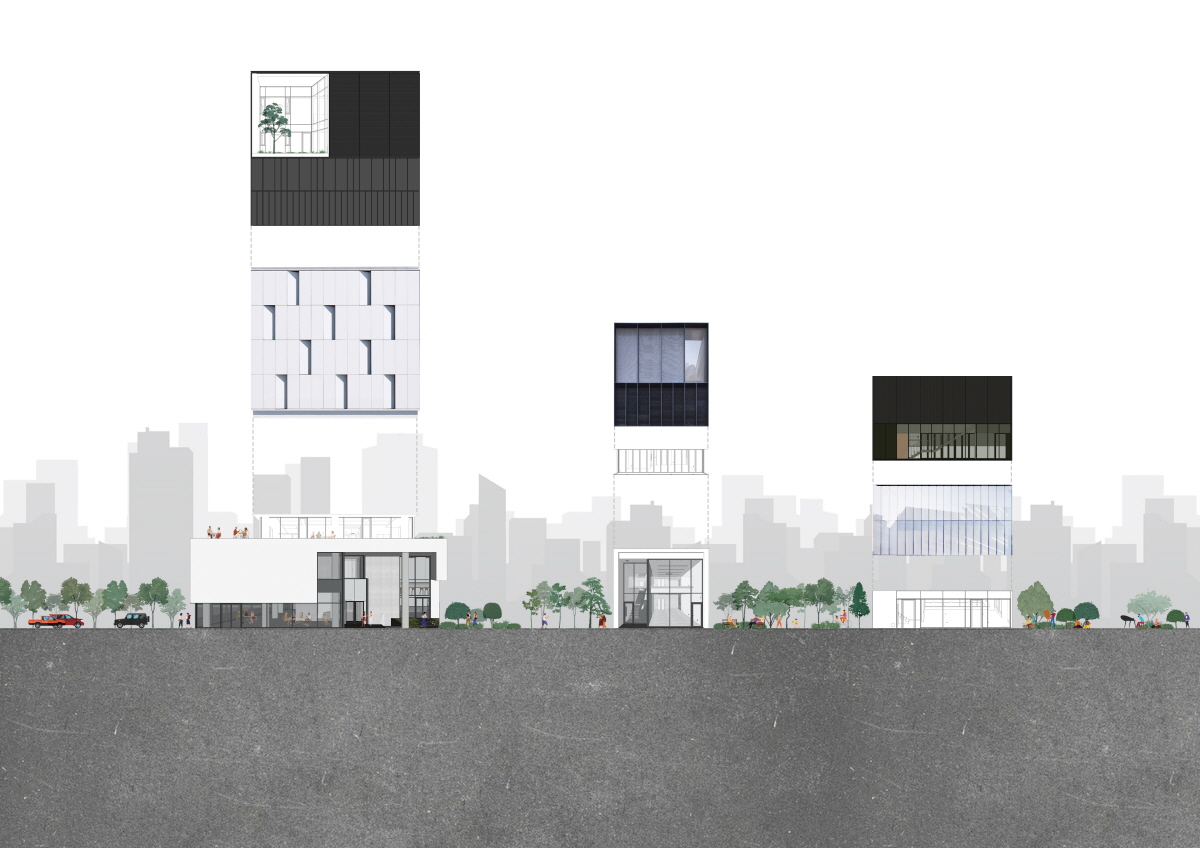

Triplet Code Imun

Triplet Code Sinsa

Setting the Scene for Neighbourhood Living Facilities

In the past, when multi-household and multi-family residential buildings were built haphazardly, as if copied and pasted, a viewpoint emerged, along with the expression ‘a house that sells houses’, that was contemptuous of this architectural type that was beginning to shape the cityscape of Korea. It is ironic that today the architectural community is making great efforts to preserve at many of them as possible. Such a viewpoint shifted to what became known as the ‘neighbourhood living facility’ as we reached the 1990s and 2000s. On the face of it, there is no reason to look down on buildings designed as neighbourhood living facilities, which is a building usage designated by architectural legislation. The story behind this unease derives from the natural reactions of architects who could not agree with the fact that, while architecture should remain an art, the logic of capital, as well as real estate, was coming to take priority above the logic of architecture. Of course, this was and is not the case for all neighbourhood living facility projects, but most clients who commission neighbourhood living facilities tend to want to make the greatest possible profit through rental income. This is made possible by designing and constructing the largest possible number of units to rent out for the lowest possible fee. So, how should one respond to this guiding notion or motivating factor behind the neighbourhood living facility?

More recently, the neighbourhood living facility has become a building type that dominates the architectural market, and there are almost no architects who do not design neighbourhood living facilities. To dominate the market is to dominate the scenery of this city. Architects respond to such a prevailing phenomenon with their own methods. Some use a classical language in the form of the building elevation, others use the form generated by legislation as their design language. Some distinguish themselves in the choice of materials for the elevation, while others respond to the logic of the neighbourhood living facilities by simplifying the structure.

All cities have their own codes according to the genetic properties of each region; in other words, there is a long established tendency to employ certain approaches and attributes which undergo a series of circulation processes as follows: creation, decline, and extinction.

Triplet Code or Neighbourhood Living Facility Code

The way Kim Dongjin (professor, Hongik University) responds is at once very architectural while also very urban. He uses the triplet code as the language to formulate his response, meaning that DNA is made up of three bases and that the combinations of these bases can create an almost infinite number of new lifeforms. His line of reasoning is that, in the same way that our lives are organised, our cities can also create countless scenarios and landscapes using these three bases. However, when we look at Kim Dongjin’s trio of neighbourhood living facility projects, we forget why we need to explain architecture in non-architectural language, like chromosomes and bases. What is strange is that he applies a single code to different contexts, namely Sinsa, Imun, and Sangsoo. At first glance, the trio of works seem very similar, raising questions as to whether this code was applied flexibly across projects to suit different contexts or whether the architect created the code with a final image more or less determined. The three projects presented in the photographs are defined by their elevations, which were segmented into three parts: an upper black level that is vertically rhythmic, a contrasting white or opaque middle level, and a transparent lower level. Upon closer inspection, however, one notes that in these projects the architect actively embraces and freely plays with a logic that governs architecture beyond the triplet code.

These works openly and actively embrace the defining features of the neighbourhood living facility, create rich urban scenery, and in architectural terms are very rational in design approach without sacrificing architectural beauty. There is no need to exaggerate the governing logic of the neighbourhood living facility through an applied architecturalised language. These three works respect the openness of the neighbourhood living facility and the societal phenomenon of neighbourhood living facility.

The foremost feature of these three works is the open lower floors. This is not the kind of openness that cultural or public facilities prioritise, but rather an openness that maximises exposure to the first floor, which houses commercial units. Especially in the case of Imun and Sinsa, the architect was eager for the lower level to be made up of maisonettes. This is not for the sake of maintaining elegant architectural proportions, but in response to the fact that the rent on the second floor is significantly lower than on the first floor; the architect proposed a lower level that could be flexible, allowing tenants on the first floor to occupy the second floor (if they so wish). This dominates the streetscape at ground level. The two-storey scale, rather than a typical one-storey storefront, works to the advantage of the tenants as it does not overwhelm the human scale of the street in an urban architectural sense. However, at the same time, in terms of the conventions of the neighbourhood living facility, it sets it apart from other neighbourhood living facilities.

And, of course, the upper floors are again divided owing to a strict piece of legislation: the architectural slant line for daylight. This is the legislation that has the greatest impact on the form and height of neighbourhood living facilities in residential areas, which means that up to 9m from the ground level, there are no setbacks, but from 9m onwards setbacks are imposed if there is a parcel on the northern side of the site. Except for the case of Imun, which is subject to a 360% allowable floor area ratio and a maximum height of 40m due to the application of the district unit plan, the same architectural slant line for daylight has been applied across Sangsoo and Sinsa, which have become the standard for the dividing line between the design language pursued on the top floor and on the middle floor. Of course, the difference in floor area between the two creates terraces, which can also be a factor in the type of business in which a tenant will be engaged in the near future. But it is not a thoughtless approach ‘because it is the legislation’. In the case of Sinsa, a setback on the middle floors separates the upper and lower floors, creating a terrace overlooking the park at the front; this was a detailed proposal by the architect, who knew from the analysis of adjacent neighbourhood living facilities that the third floor would likely also include a café. I think this is where the appeal of a neighbourhood living facility design can be located. It is not just the architectural setbacks that are important, it is also the combination of anticipated businesses and the architectural language employed that puts the puzzle together.

Triplet Code Sangsoo

Like an Office Building

Although they are located in different contexts in different regions, one could easily conclude that these three projects were designed by the same architect, mainly because of the building materials used. The choice of materials – the transparent lower floors, the dark black upper floors, and the opaque white middle floors, which are treated to distinguish them from the lower and upper floors – was shaped by the architect’s own language, like the yellow of Richard Rogers or the white of Richard Meier. In particular, the black upper floors, contrasting with the white lower floors, make the upper volume appear to float, and the vertical segmentation of the upper floor elevation creates a perspectival illusion that makes the upper floors appear longer. The three-tiered composition of the triplet code, as clearly defined by the logic of the elevations in the three-tiered composition of the Palazzo, simplifies the process of designing a neighbourhood living facility that has to respond quickly to its environment.

In turn, this meticulous and detailed architectural language manipulates the guiding principles of the neighbourhood living facility. In the architecture of neighbourhood living facility, where the main concept is to ‘maximise floor space at minimum cost’, a design solution that responds to and uses the logic of neighbourhood living – rather than insisting on the use of a specific architectural language – reverses the logic of neighbourhood living and welcomes new possibilities. The way in which the lower floors are opened up to the city in anticipation of (or even to encourage) the businesses that will enter the lower floors; the way in which the lower and upper floors are divided to provide terrace space that will welcome business owners; and the rhythm of an architecture that focuses on the upper floors that are most recognisable as neighbourhood living facility: all lead us to ask whether the trio of neighbourhood living facility works with triplet codes will simply end up known as ‘neighbourhood living facility’ landmarks.

We often use the expression ‘foreign-like’ when we go to a nice place. In fact, there are many nice places in Korea, and not all foreign places are nice, so I am not sure if it is appropriate to use this expression, but it is a common one. A similar expression is ‘office building-like’. Kim Dongjin’s series of neighbourhood living facility works are, in a nutshell, ‘like office buildings’. In fact, it is not difficult to design a neighbourhood living facility that looks like an office building. All that is needed is a client budget and an architect’s efforts. But it is not easy to design an office building-like neighbourhood living facility that reflects the logic of the neighbourhood living facility as it is, or even reinforces it, and which adequately reflects an urban context and architectural language. And the fact that his projects have actually been rented or sold as office buildings may be an indication of the new possibilities for the neighbourhood living facility as one that can be manipulated by architects who are not satisfied with the motives behind the neighbourhood living facility.