SPACE January 2024 (No. 674)

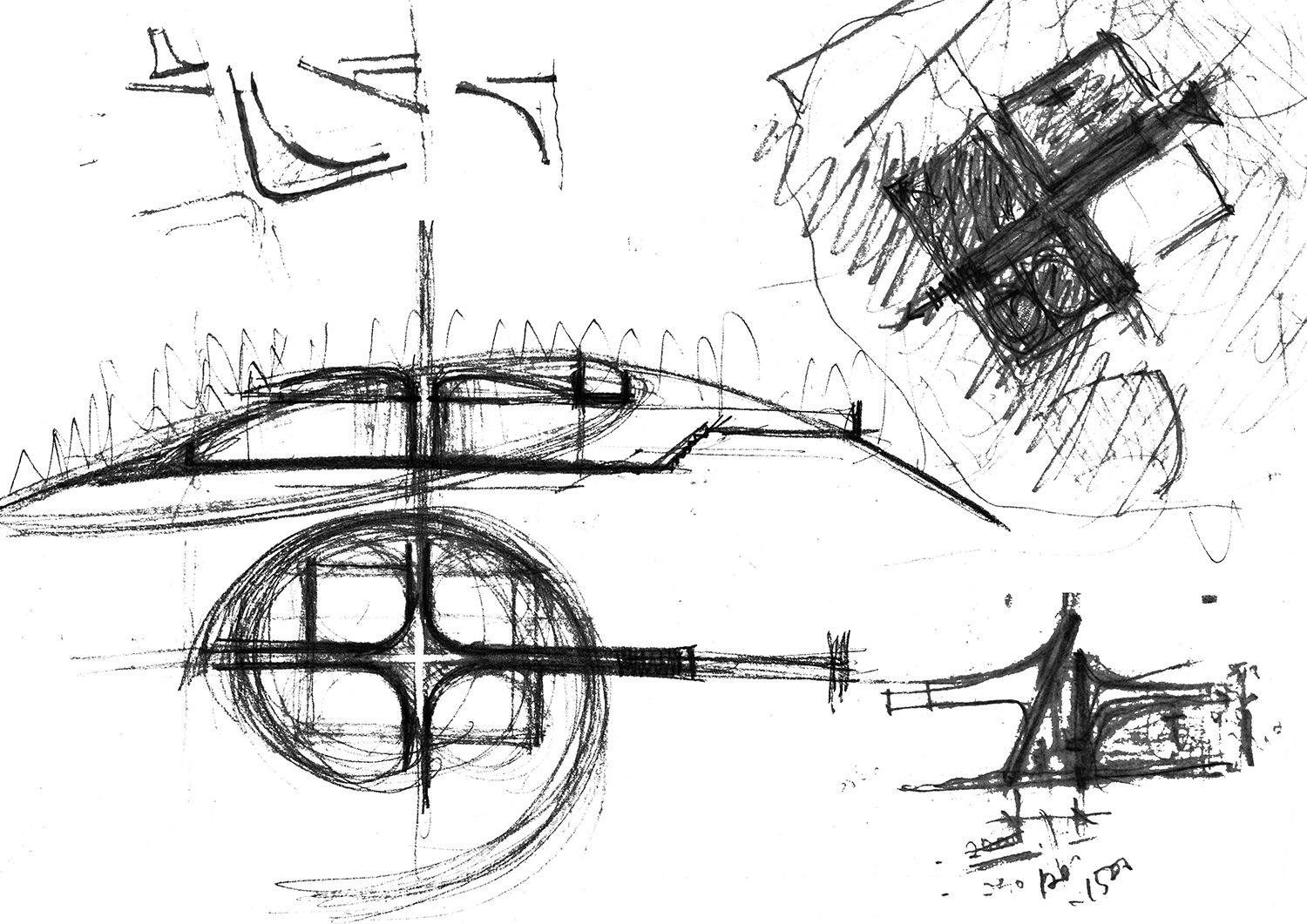

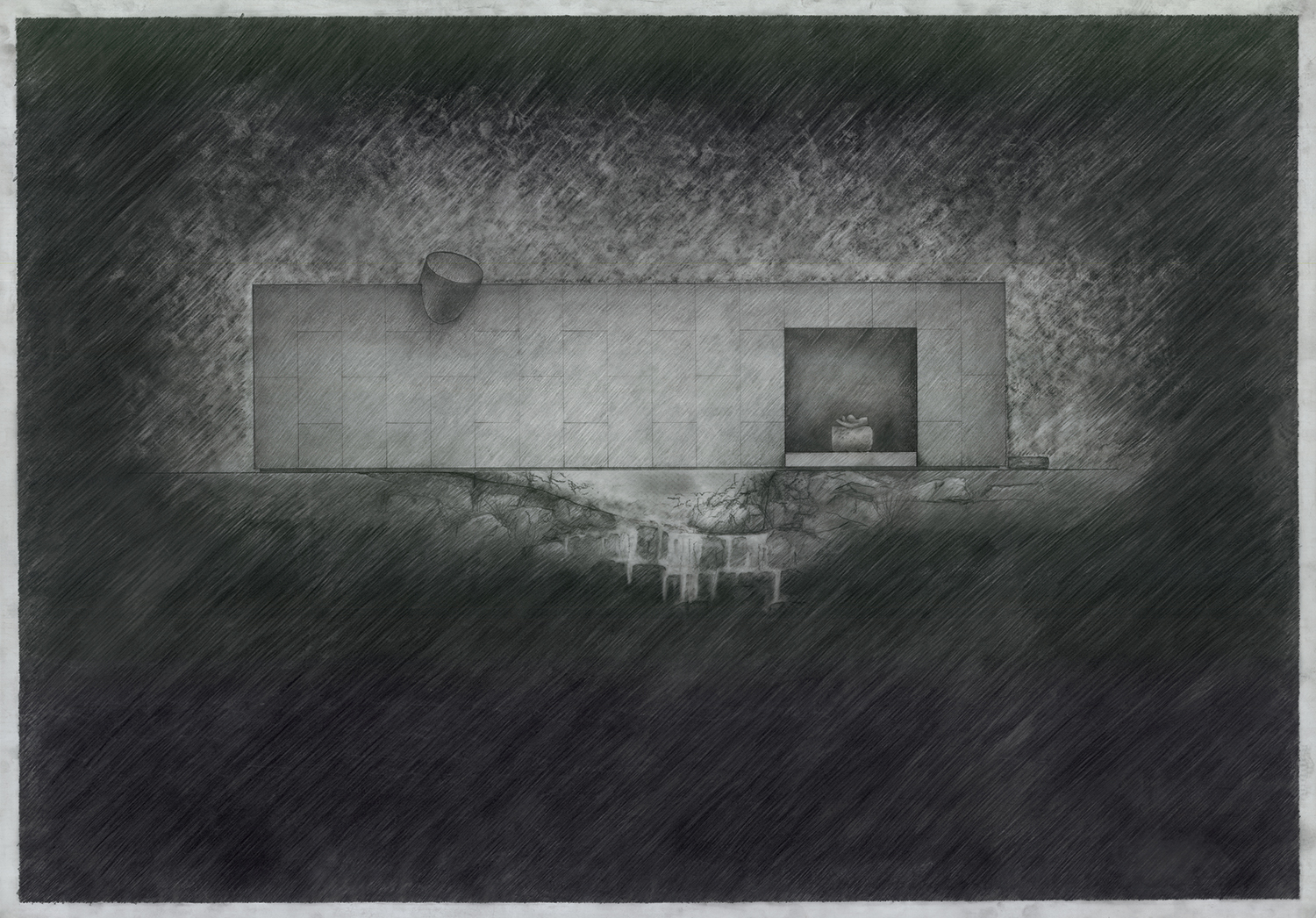

Initial sketch of Voice of Heaven (2023) by Yoo Ehwa

Earth and Nature: Ontological Architecture, Phenomenological Architecture

Yoo Ehwa, well-known as the daughter of Itami Jun (Yoo Dongryong), is also an architect who has emerged from the reputation of her father. She learned a respect for nature and the earth and the need to be modest from her father. Both architects have emphasised locality, indigeneity, warmth, and vitality of materials, and sought an architecture that is ‘brewed’ when it permeates nature and region. What they pursue is an ontological and phenomenological architecture, without referring to Heidegger’s concept of the earth, that reveals an essential truth through the nature of the earth and awakens the five senses.

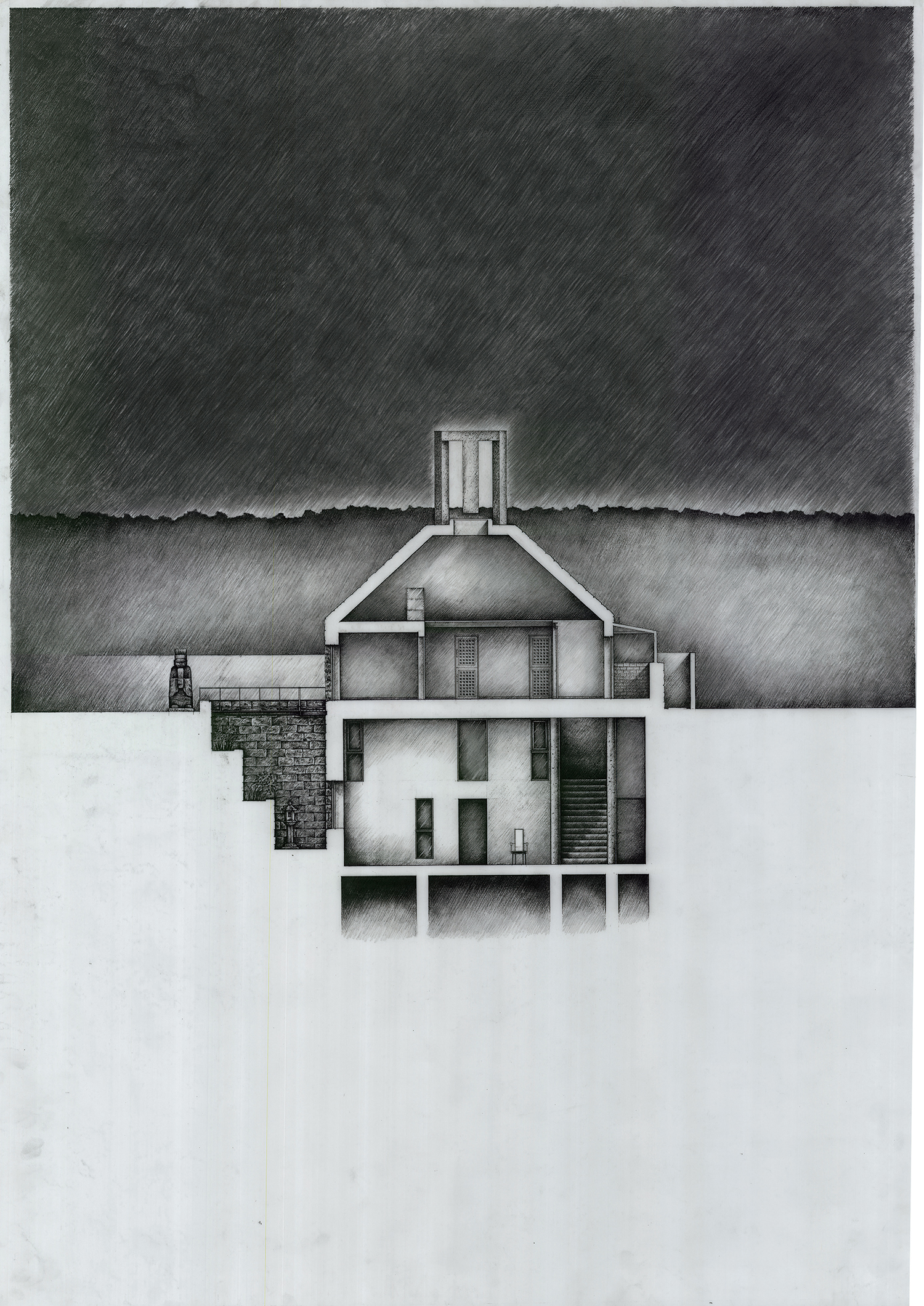

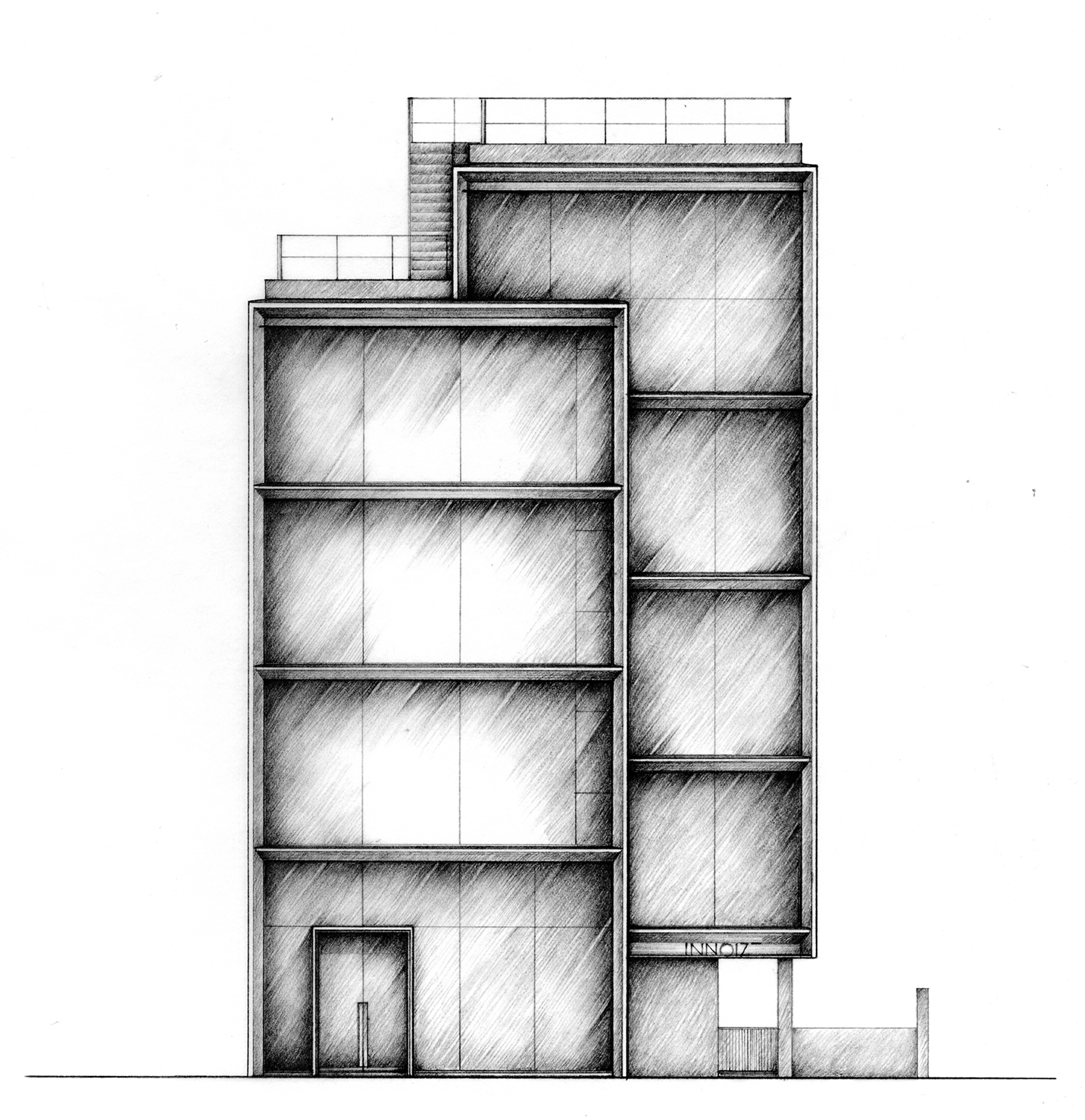

Drawing of Carved Tower (1988) by Itami Jun / Image courtesy of ITAMI JUN Architecture & Culture Foundation

Rock and Mass, Water and Line

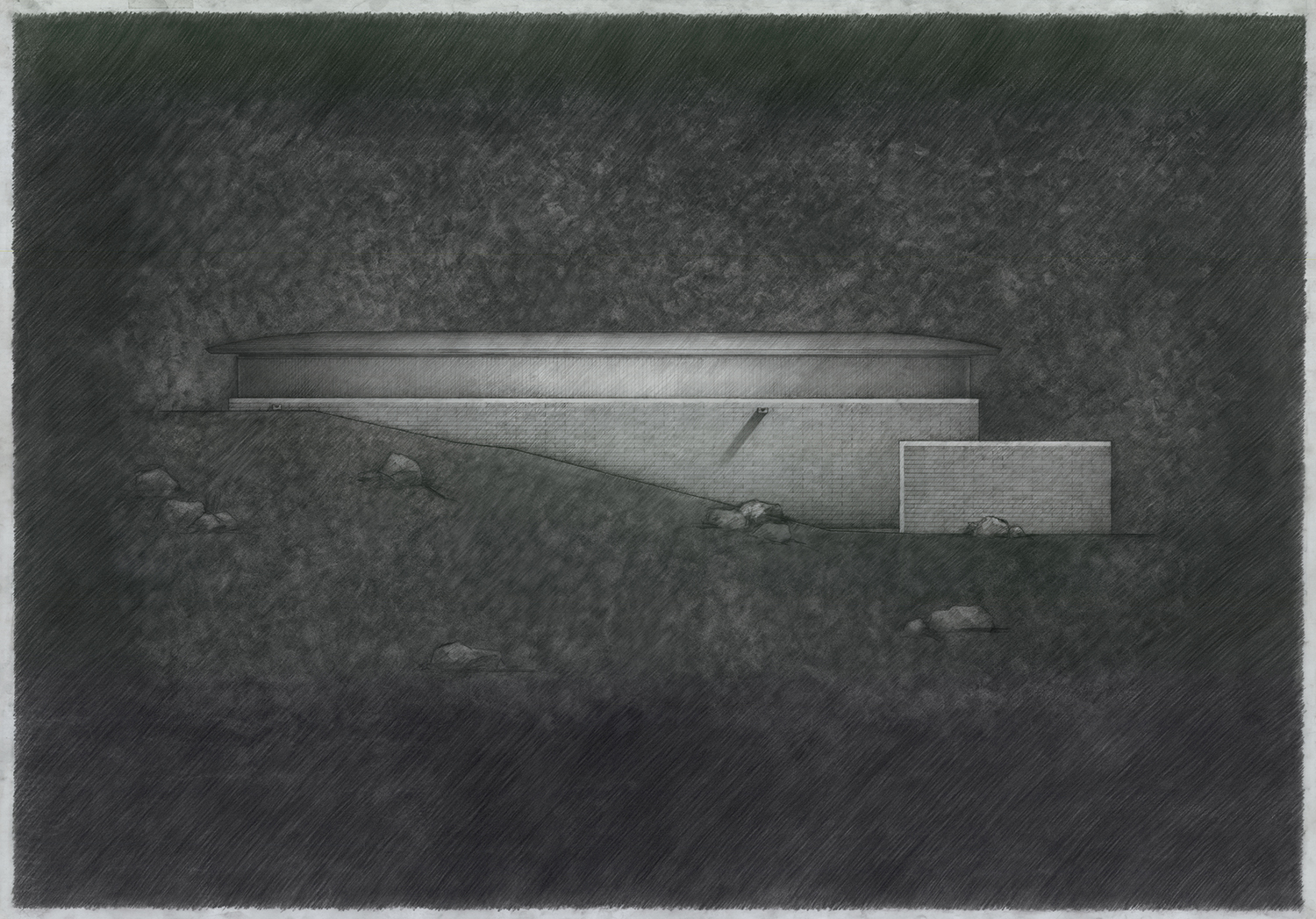

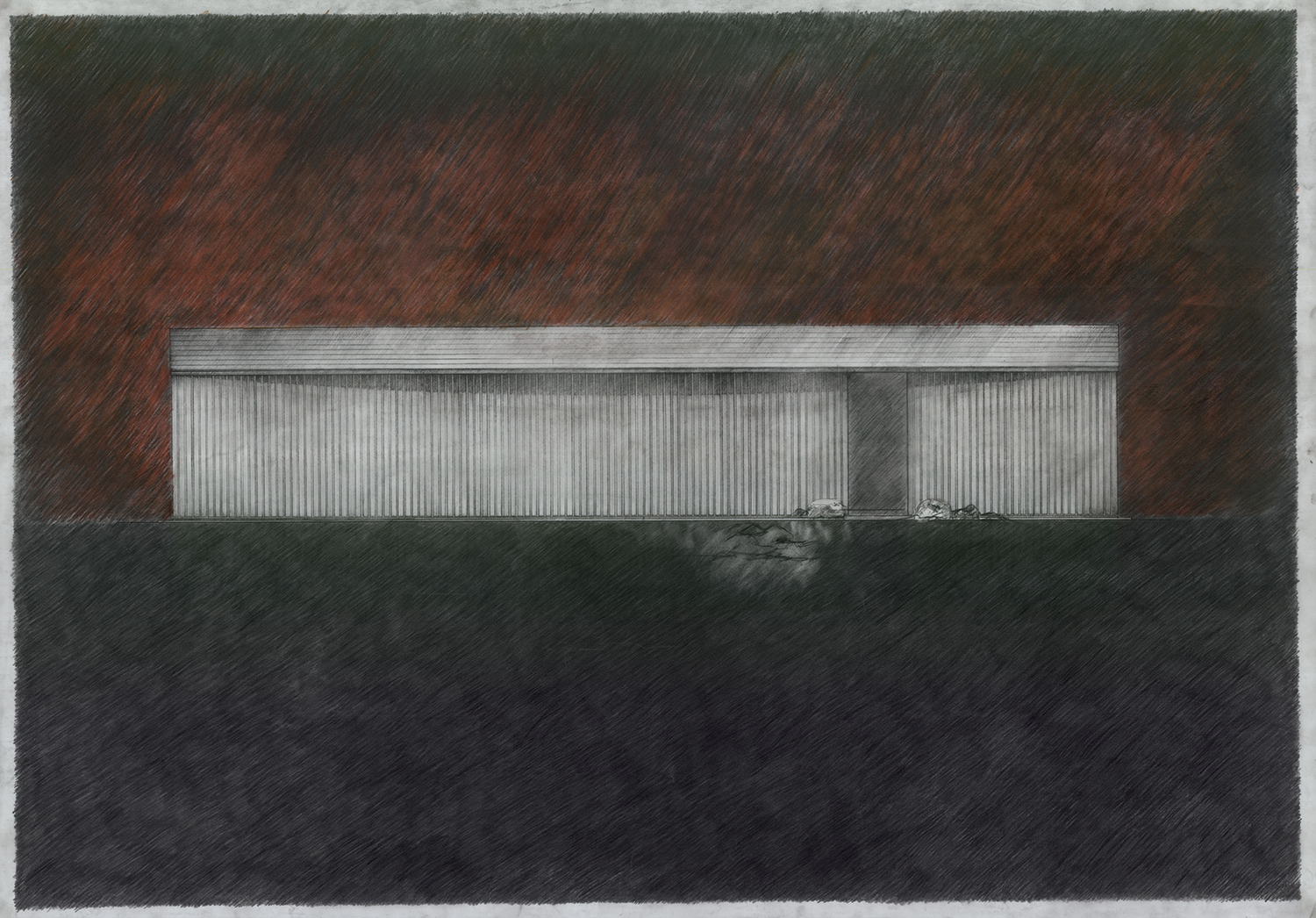

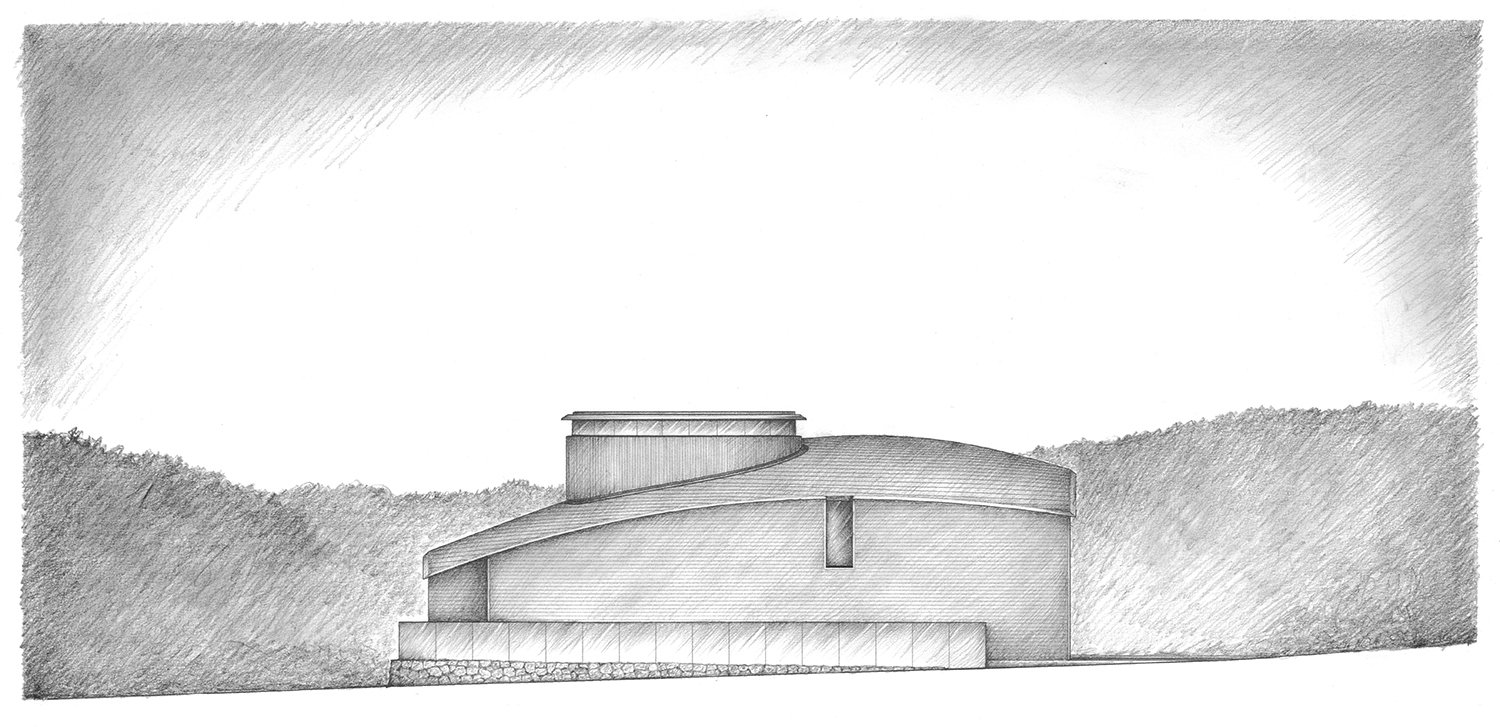

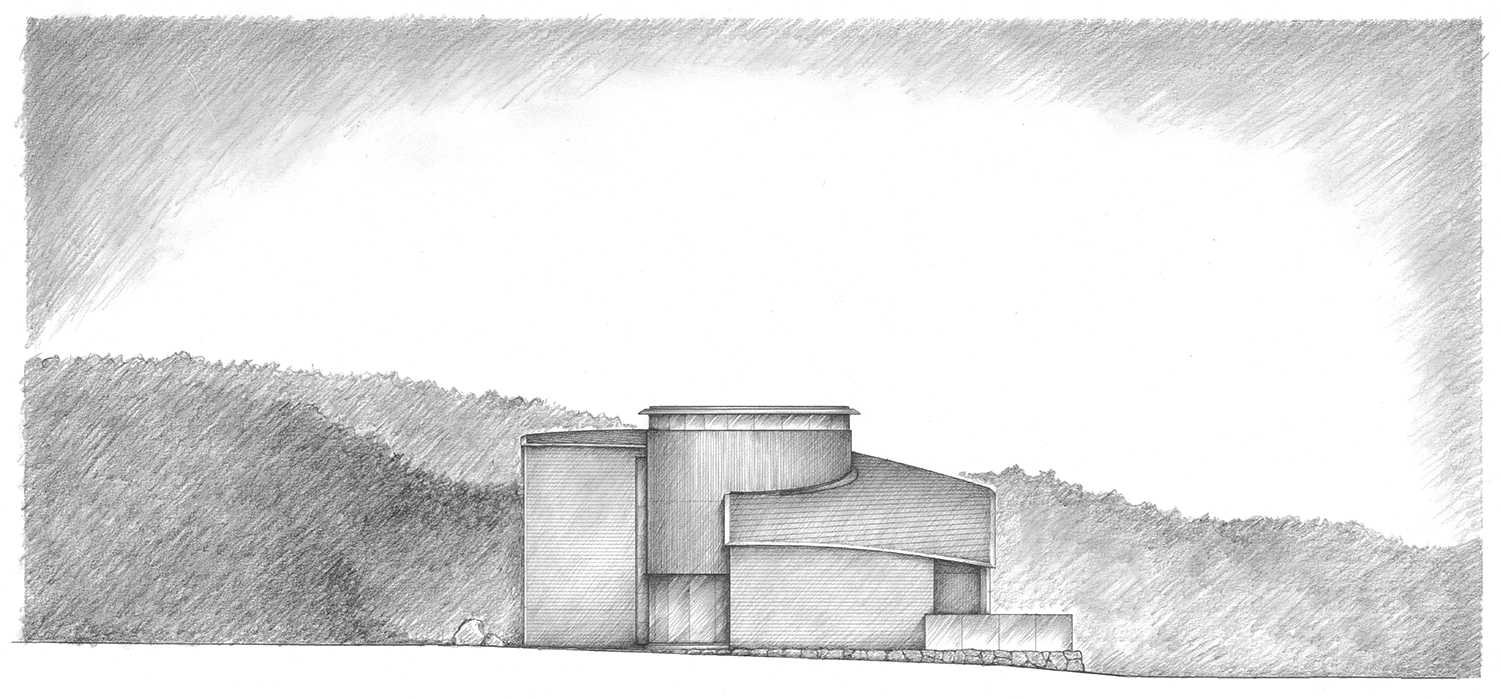

Throughout his architecture, Itami Jun pursued massing compositions in which a single heavy stone symmetrically extends out like concentric circles. This includes his early works, such as Onyang Folk Museum (currently Gujung Art Museum, 1982), Carved Tower (1988), and Water, Wind, Stone Art Museums (2006). While crude and rough volumes characterise Itami Jun’s work, Yoo Ehwa’s architecture is in tune with the properties of water. Water has both a round and soft aspect as well as a sharp and keen aspect. Water flows slowly, but sometimes it forms a whirlpool or can be transformed into keen lines. The floor plans of Sihojae (2023) play with a gentle flow that envelops the space, but its roofline is sharp and acute. The façade lines of INNOIZ Office Building (2014, covered in SPACE No. 564) and He.ART Building (2019) are also both flowing and rigid in aspect.

While Itami Jun employs blunt massing in his architecture, Yoo Ehwa’s demonstrates a command of sharp lines. In her architecture, a taegeuk-like composition of different water flows that swirl and balance each other appear across plans and sections. Sihojae shapes its layout through swirling water flows, while Voice of Heaven (2023) operates on diagonal lines, and Sinwondong Office & Residence (2021) features curves facing each other like a taegeuk pattern. One section of the INNOIZ Office Building has an interlocked composition formed from two layers and volumes. The compositions can be described in various ways, such as rotating flow, point symmetry, and dynamic balance. While Itami Jun sought a static centrality, Yoo Ehwa has sought a dynamic balance. In her architecture of such a dynamic aspect, sequence becomes even more important than in the architecture authored by her father. While he chose a face-to-face approach to his buildings, she prefers a meandering sequence to shape walls and paths as methods of approach to her building.

Drawing of Mother’s House (1971) by Itami Jun / Image courtesy of ITAMI JUN Architecture & Culture Foundation

From Element to Vibration, from Vibration to Flow

Beginning with a building of many elements, such as Mother’s House (1971), Itami Jun gradually reduced the number of features, eventually culminating in a single mass without any distinguishing elements. Where Itami Jun was informed by the resonance or vibrations produced by the monolithic space that he finally reached, Yoo Ehwa transforms any such vibrations into a flow. Since her architecture begins without elements, the transformation of flow across planes and sections creates various works of architecture. Therefore, it could be said that Yoo Ehwa begins where Itami Jun left off.

Their collaboration projects reveal the possible middle point and meeting of minds. The decade between her return from New York in 2001 and his death in 2011 marks a period in which their architecture blended together. The Ophel Golf Club House (2008) and Seowon Golf Club House (2012) reveal the coexistence of his centrality and her flow. Office in Bangbae-dong (2007) features both mass and flow by interpreting the taegeuk pattern, in which yin and yang rotate and balance each other, on a right-angled elevation of a cubic volume. The ITAMI JUN Museum (2022), in which she strived to ‘design using my father’s language, while suppressing myself’ has a sense of mass, and emphasises Itami Jun’s blunt and heavy feel rather than the sharpness of her proportions.

Earth and Mass, Fabric and Line

Where do the qualities of line, flow, and balance in Yoo Ehwa’s architecture come from? If she inherited a respect for the land and a sense for materials from her father, can the properties of line, flow, and balance be found in her mother? Her mother, a fashion designer, ran a boutique until Yoo Ehwa’s middle school years, so presumably she was exposed to cloth and fabric from an early age and acquired a feeling for the properties of line, flow, and fluidity of textiles. Her sense of interior design and detailing also seems associated with her mother; She recalls ‘My mother taught me the difference between visible and hidden threads, and the importance of a single button, even in the same garment, and this influenced on my interior design and detailing.’* She came to Korea from Japan when she was in elementary school and was raised by her grandmother who was good at painting. Her grandmother also nurtured her sense of materiality, and she says she still vividly remembers when her grandmother turned squid shell inside out and dried them to make drums. Having no choice but to major in interior design at university because her father argued that architecture was a difficult working environment for women, she came to regard fabric, furniture, stairs, and architecture as on a continuum of objects, and the flexible line of cloth seems to have been realised in her larger scale architectural projects. Yoo Ehwa states that she has sought a sense of diminished presence and permeability rather the creation of heavy objects. What she pursues is a flow into nature and melting into one’s surroundings.

Drawing of Water Art Museum (2006) by Itami Jun / Image courtesy of ITAMI JUN Architecture & Culture Foundation

Drawing of Wind Art Museum (2006) by Itami Jun / Image courtesy of ITAMI JUN Architecture & Culture Foundation

Drawing of Stone Art Museum (2006) by Itami Jun / Image courtesy of ITAMI JUN Architecture & Culture Foundation

The Flow of a Hospitable Vortex

Sihojae, meaning ‘a bow that shoots towards time’, is located on a site surrounded by the lower reaches of the Palgongsan Mountain. Following the entry sequence along a long wall, we were welcomed by fluid lines of two wings wrapped around a garden. High and thick at one end and sharp and pointed at the other, the two wings interlock as in a taegeuk pattern. The garden is natural, as if it originally existed there, giving the impression of being in another world. Here the architect attempted to forge a separation from the outside world. But, instead of using a complete and static circle like an earthwork, she made the two wings slip and flow. As expressed in the early sketches, the two embracing wings with arms flow like swirling waves. A single line flows out and connects to the client’s house.

Drawing on the the flow of mountain stream, she added ‘chu-imsae’ (Yoo Ehwa used this term, meaning exclamation during Korean traditional music) to the flow of nature through the slender and flying roofline. To make nature take a lead role and architecture a supporting role, while still seeking permeation between conventional boundaries, zinc and exposed concrete have been painted with black stain. In Sihojae, walls play a very important role. They extend the building, allowing it to flow, and provide privacy by screening the surrounding buildings. The wall encloses the irregular volume of the east wing of guesthouse. The wall of cedar rows is tall enough to shield the neighbouring buildings, but it doesn’t feel completely closed off, leaving roofs and mountain views above the wall. It strikes a balance between closed and open. The cedar louvers on the east side filter westward light and provide privacy, while casting shadows that create a sense of the passage of time.

The layout of Sihojae seems to welcome people with open arms, wings extending, while the client’s house is regarded as the head. The ‘hospitality’ implied by this layout was also felt in the client’s personality as he introduced the space to us during our visit. Highly knowledgeable about architecture and art, a collector of artifacts and modern paintings himself, he trusted his architect wholeheartedly, staying out of the way and allowing her to scale the heights of her abilities. At the end of the tour, I was deeply impressed by the way the client and his wife bid me farewell, as if to a family member leaving their home.

A Sanctuary of Concrete Fabric

Voice of Heaven (2023) is located on a hill surrounded by pine trees. A curved wall of exposed concrete bends and curves through the pine trees like cloth draped or water flowing through the terrain. The curves and straight lines of the wall provide contrast and balance, almost resembling a biblical tabernacle or tomb on the hill. With the intention of showing different scenes within the small building, the architect creates a walking sequence along a contemplative path up to the hill.

Nominated by the university’s president to work on the prayer room project, she sketched and designed the building in one sitting, as if inspired by God on the train back to Seoul from her site visit. The idea was to place a cross in the heart of the university campus, which resembles the shape of a sheep. The cross was transformed into flexible lines that create a flow, and the two spaces that divided by the cross become a prayer room and a group meeting room. Her theme of rotating, balanced flow is naturally combined with the cross. As can be seen more clearly in the early sketches, the curved walls curl into a vortex, uniting with the curve of the cross to reach the centre.

Yoo Ehwa intended for the building to evoke various emotions, without rising in prominence above the site, and to inspire religiousity without revealing the cross. Instead of adopting the chapel design with cross-shaped skylight to carve the cross into the plan, she designed the space under the cross-shaped skylight as a narrow passage. This intends to devise an experience of passing through suffering and contemplation by following the light of the cross. In the hallway, a staircase comes into view with a cross hidden above it. The shining brass cross is reminiscent of the cross on the hilltop of Golgotha. Exposed concrete with no elaborate finish due to the limited construction budget and the minimal approach to details that guide the building’s asceticism.

The prayer room is oriented toward a corner to increase concentration. A cross that faces the congregation hangs at this corner. A horizontal window below the cantilevered wall supporting the cross provides a view of the courtyard. In this way, the prayer room is open as well as closed. Not completely closed off, it allows students to focus on contemplation and prayer in a relaxed atmosphere. During our visit, several students freely entered, prayed, and left. What a rare sight to see young people spontaneously praying and meditating! Like the lyrics of a gospel song playing in the prayer room, it felt like God’s hope had been realised in a building through the architect’s vision. For Yoo Ehwa, respect for the earth and nature is no different from faith in God. Balancing and breathing with nature is the same as respecting God. The Voice of Heaven speaks to the heart with its exquisite balance of the artificial and natural, straight and curved, concave and convex, open and closed, line and plane, and the light and dark.

Drawing of INNOIZ Office Building (2014) by Yoo Ehwa

Considered Curves and Balanced Diagonals

Itami Jun and Yoo Ehwa are both inspired by the landscape and terrain in which their projects are located, but where do they find inspiration when they design within a city? She says when she designs a building in a city that she wants her buildings to permeate the surrounding buildings as if they had long existed there. Her statement can be applied to both nature and cities. It’s not just about making a building resemble its natural surroundings, but it’s also about making it depart from its surroundings.

The west wing of Sinwondong Office & Residence is office, while the east wing is residence. The two buildings face each other with curved corners as an expression of their considerate attitude. It is a recurring theme of flow that can be described as point symmetry, rotation, diagonal, taegeuk, and balance. Curves are appropriately distributed between the office, which opens to the mountain in the north, and the client’s room, which opens to the south. The theme of diagonals and balance continues inside. The high ceiling space of the living room and the void of staircase have also been arranged diagonally. In the section, there is a void connecting the first and second floors, and a staircase leading to the basement in the diagonal direction.

From Architecture of Being to an Architecture of Flow

Itami Jun’s architecture of presence, a phenomenological architecture, is evolving in a different direction in Yoo Ehwa hands to escape his long shadow. Her architecture of permeations, which does not impose its existence on a space, creates a rotating balance like flowing water in a fluid, sharp and acute way, sometimes creating a whirlpool. Now it is time to observe the fast-flowing future of Yoo Ehwa’s architecture of flow.

Drawings of ITAMI JUN Museum (2022) by Yoo Ehwa

* Anecdotes related to Yoo Ehwa’s mother and grandmother are based on interviews during the visit to her projects.