The KAIT Workshop’s interior creates the ambience of a tree-filled forest.

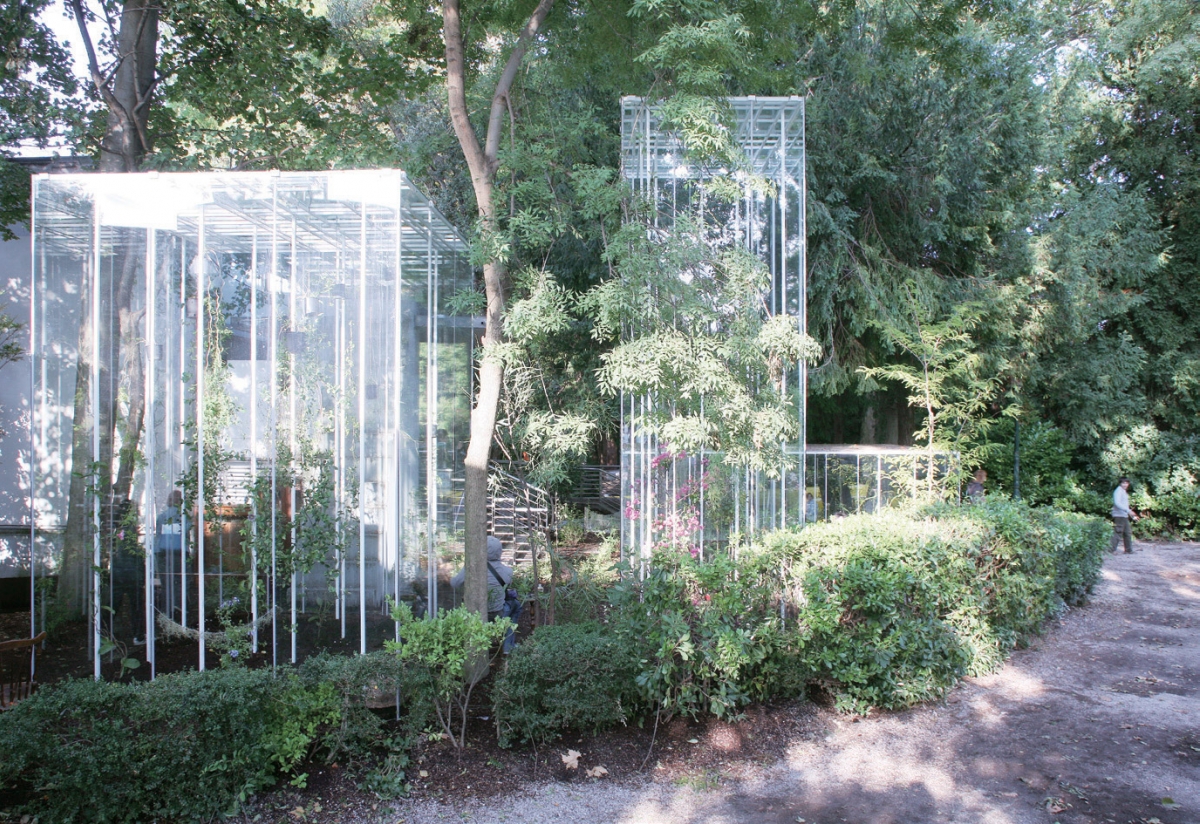

For several years the Ishigami studio was more involved with exhibitions and the production of ‘artworks’ rather than building for public or private clients. His show at the Barbican Centre in London presented an architectural installation entitled Architecture as Air, weighs a mere 300g, and fifty-three impossibly thin columns support a similarly skinny beam, creating a 3.8m high colonnade stretching the length of the Curve gallery. Equally, it can be seen from the similar structure for the Japanese pavilion at Venice Biennale in 2008. Ishigami once made a table that is 9.5 × 2.6 × 1.1m and has a topboard of only 3mm thick for the horizontal plan. In order to keep it flat and stable, the steel plate board was bent so dramatically to form a full curl and a half. The table is a drawing (a long line and four vertical lines), is a work of architecture (four pillars and a roof), and is a site to host a landscape. Hopefully, his fame brought clients and Ishigami is now involved in about ten new projects, all in development.

The Japanese pavilion at Venice Biennale 2008

In contrast to the urban KAIT Workshop building, the Botanical Farm Garden Art Biotop in Tochigi, Japan, to be completed this summer, is a pure outdoor project that looks as natural as it has been completely created. This is to deconstruct and construct a new environment that covers 60,000m2. Two pieces of land allocated to the dual project: a hotel and a garden. The site accorded to the hotel is planted with a forest of trees while the site for the garden is just an open field. Ishigami decided to switch both sites, by uprooting and replanting all the trees one by one that have a quite dense display. As the site for the garden was a former rice field there was still an irrigation network that has been restored and reused. The image drawn by Ishigami is a constellation of micro ponds spread all over the intervals between the trees. In fact, 160 ponds were dug out so that the water surface of the ponds and the surface of the ground in moss would be at the same level. Stones in path provide a route to walk around the garden. The mirror effect of the water surface of the ponds is just magical.

A piece of nature has been recreated here, in much more efficient manner with a design completely drawn out for the best. The danger in architecture is that sometimes the images produced for prints are so perfect that it is difficult to challenge them with the actual experience. That will be a failure, but it can be the opposite and the experience of the building, the being-there under a changing light, among trees and plants, under the rocks and the slope roof is becoming an extraordinary moment of magic, or just a plain comfort in living a space finally domesticated and inhabited.

In House of Plants, the natural environment has been transported indoors to allow for the enjoyment and benefits of nature within an urban context.

Inevitably Japanese architects are confronting the question—that exists everywhere else, but not at that so tiny little scale—of the private family suburban house. Houses with plants (2010 – 2012) is one rare example of Ishigami’s proposals for individual architecture. The land is 100m2 and is used without wasting any square foot in the sense that the house limits take in the total surface area. Mortar-finished panels are hung on a steel framework. These panels constitute the exterior walls of the building punctuated with large openings. On the ground level, part of the floor is covered in soil and planted with vegetation like a miniature forest that grows within the living room’s double height volume. The natural environment has been transported indoors to propose a new life style, allowing for the enjoyment and benefits of nature within a completely enclosed urban context. Another living space, situated on a mezzanine level and accessible via a ladder, seems to float above the plants. The relationship between the interior and exterior has been twisted to the benefit of the owners who profit from the constant changing of light and atmosphere throughout the different seasons.

The site, more than the programme, is constant inspiration for the architect, who discovers his guiding concepts according to basic typology of sites: the sea, the rocks in the mountains, the forest. In Denmark, the on-going project for a House of Peace (2014 – present) in the port of Nordhavn, the sea is the site. At the seaside, the building anchored on the bottom of the sea introduces the salt water as the natural floor, while the concrete curvy ceiling plays with the image of clouds: a seascape as simple as it comes. Accessible through a tunnel underwater, the platform is surrounded by the sea and is a space for meditation and the experience of a natural and artificially made landscape. Visitors are invited to use small boats to travel around this 3000m2 space. The sea is a constituting part of the architecture: the temperature is regulated by the seawater, which gradually absorbs the heat from the sun, and this water stores energy for thermal use.

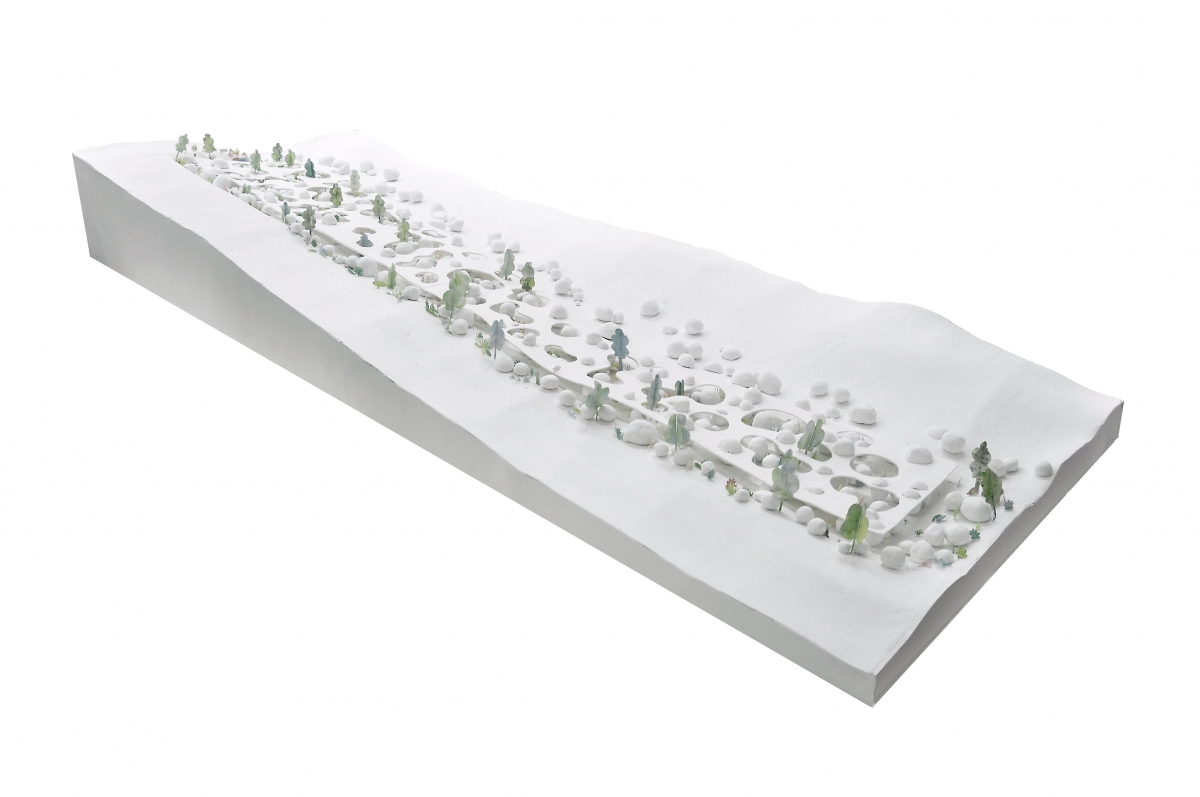

For the 8 Villas in Dali, the boulders are used as a structural component. / Model of 8 Villas in Dali

Boulders can be sometimes like big round balls– granite chaos–and when punctuating a piece of land they offer a manner of natural structuring to be used in architecture. Ishigami took it an actual component, as a given data to straightforward use per se. The commission was to build 8 Villas in Dali, China (2016 – present) on a mountain site close to a river. Another important advantage to this project, including the landscape within the architecture, is the avoidance of a new real estate developer transforming the local scenery in the

coming years. Boulders were all around and the architect decided to keep some of them, move away others or just change their positions for some others. This is the structure of the building and instead, as the programme specified, of separating the eight houses, he gathers them under a 300m single long roof fixed on the boulders. The roof has several large openings