SPACE October 2023 (No. 671)

Last month, SPACE assessed the activities of the Mid-Size City Forum (co-principals, Lee Janghwan, Lee Sanghyun) and raised awareness of the changes facing medium-sized cities in Korea (covered in SPACE No. 670). This time, it is the hyper-megacity rather than large city that is getting bigger by the day, as they accrue people and technologies. It is not a situation unique to Korea. In response to this phenomenon, Chun Euiyoung (professor, Kyonggi University) looks for traces of the future city in terms of ‘megacities’, which are more than just metropolises, and ‘megaregions’, which are more than just countries. Also, Chun proposes an urban architecture strategy that will view Korea’s national territory, from Seoul to Busan, as a single metropolitan hub and One City-State.

Image of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City (1898) created using AI

Philip Kotler, author of Marketing 5.0, predicts that future technological developments will accelerate digital transformation and calls for innovation that leverages new technologies. What is noteworthy is a period of singularity that occurs as digital technologies develop. Raymond Kurzweil believes that the development of human thought is linear, but the advancement of technology is exponential, leading to a singularity of vision around 2045 when AI will overtake the sum of human intelligence. Based on Kurzweilʼs ideas, Peter Diamandis proposed the ‘6Ds’ as a framework for explaining exponential evolution. The 6Ds are digitalisation, deception, disruption, demonetisation, dematerialisation, and democratisation. He believes that the exponential development of technology will make available resources abundant and that the new future created by the advancement of information and communication, and life science technologies and knowledge, will differ from the previous industrial revolution.▼1 In the face of this exponential evolution, management experts such as Salim Ismail emphasise the importance of companies articulating a ‘Massive Transformative Purpose (MTP)’ rather than increasing human capital or physical assets.▼2 They believe that if an organisation can clearly articulate the purpose and reason for innovation that can make a big difference to an entire industry or even the planet, it will be easier for them to form a platform enabling exponential growth. From this perspective, if we replace ‘organisation’ with ‘city’, it is time for cities to start thinking about these possibilities.

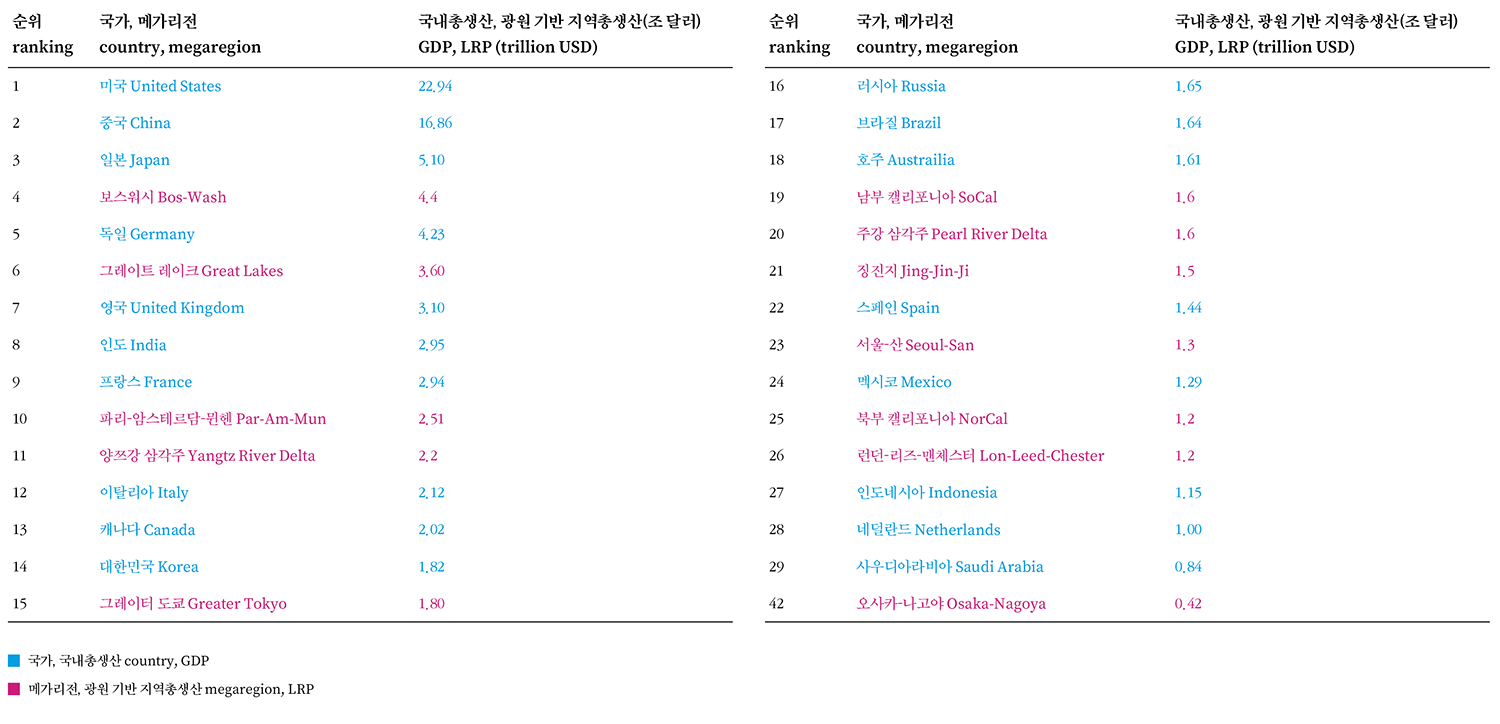

Ranking of countries and megaregions by economic size from 2019 to 2021. The world economy is shifting towards being run by megaregions rather than nation-states.

What Will Change the City

What keywords define the future of urban architecture? The main keywords identified using AI analytics are transportation logistics, digital transformation, carbon neutrality, and population change. With these four key ideas, we will explore the future transformation of urban architecture.

First, transportation logistics encompasses technologies such as autonomous vehicle (AV), urban air mobility (UAM), transport drones, purpose-based mobility (PBV), and smart logistics, and is an integral part of the future of urban architecture. These technologies will improve urban mobility, build greener transport systems, and create new mobility landscapes such as skyports and hyperloop terminals.

Secondly, digital transformation gives rise to a number of new arrivals in the various smart cities. Technologies such as blockchain, which stores data to ensure reliability and convenience; robotics, which takes over logistics delivery and risky tasks; and digital twins, which simulate the real world in a digital environment to enable analysis and prediction, are the precursors to a new digital transformation.

Thirdly, carbon neutrality is about making the whole city a low-carbon ecosystem. Korea has a 2050 Carbon Neutrality plan. It aims to reduce carbon emissions as much as possible but to capture or absorb carbon where it is unavoidable so that net carbon emissions will be ‘zero’. According to data from the Ministry of Environment, greenhouse gas emissions peaked in Europe more than 20 years ago, while Korea saw a decline for the first time last year. Coal power still accounts for 40% of the country’s energy generation, and renewable energy penetration is only 7.4%. Although there may be many upcoming challenges, equipping our economies and cities for a low-carbon future is a global challenge that is growing in importance.

Finally, on population change, the world’s population has exploded since 1950, with two-thirds of it absorbed by cities. The United Nations (UN) estimates that the worldʼs population will peak in 2080 and reach around 10 billion people by 2100.▼3 Ben Wilson, author of Metropolis, says that as the world’s population has grown, we have transformed into an ʻurban species’ over the past six millennia.▼4 The number of cities with a population of 10 million or more increased from 9 in 1985 to 19 in 2004, 25 in 2005, and 34 in 2020. In addition, the number of megacities with a population of 20 million or more increased to 12. The world will be changed by the competition between these megacities in the future.

By the 1960s, architectural movements such as Archigram, Archizoom, and Metabolism emerged, along with futuristic cities in various guises, including Peter Cook’s Instant City, Ron Heron’s Walking City, Buckminster Fuller’s Triton City, Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sagami Bay Marine City, and the Aquapolis for 1975 Okinawa Expo. How do we see future city today? Future cities that have recently emerged are digitally enabled smart cities. Blockchain-based smart cities like Innovation Park see cities governed by an ‘algocracy’, or democratic decision-making based on ‘trust-less’ algorithms and centred on trust. The utopian city of Telosa, conceived by United States billionaire Marc Lore and designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), is egalitarian, with local communities sharing and managing the core territory. Also planned as part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the NEOM project’s THE LINE is a linear city 200m wide, 500m high and 170km long. The city has been planned so people can access nature within a two-minute walk and major facilities within five minutes. Although several issues have come to light, such as the politics behind it, the challenges of the desert climate, accusations of greenwashing, and the issue of industry and population influx, the idea of a linear, compact city based on public transport rather than private vehicles is innovative. Other futuristic planned cities include the Smart Forest City, a carbon-neutral botanical garden city proposed by Italian architect Stefano Boeri, and Akon City, a cryptocurrency-based city in Senegal.

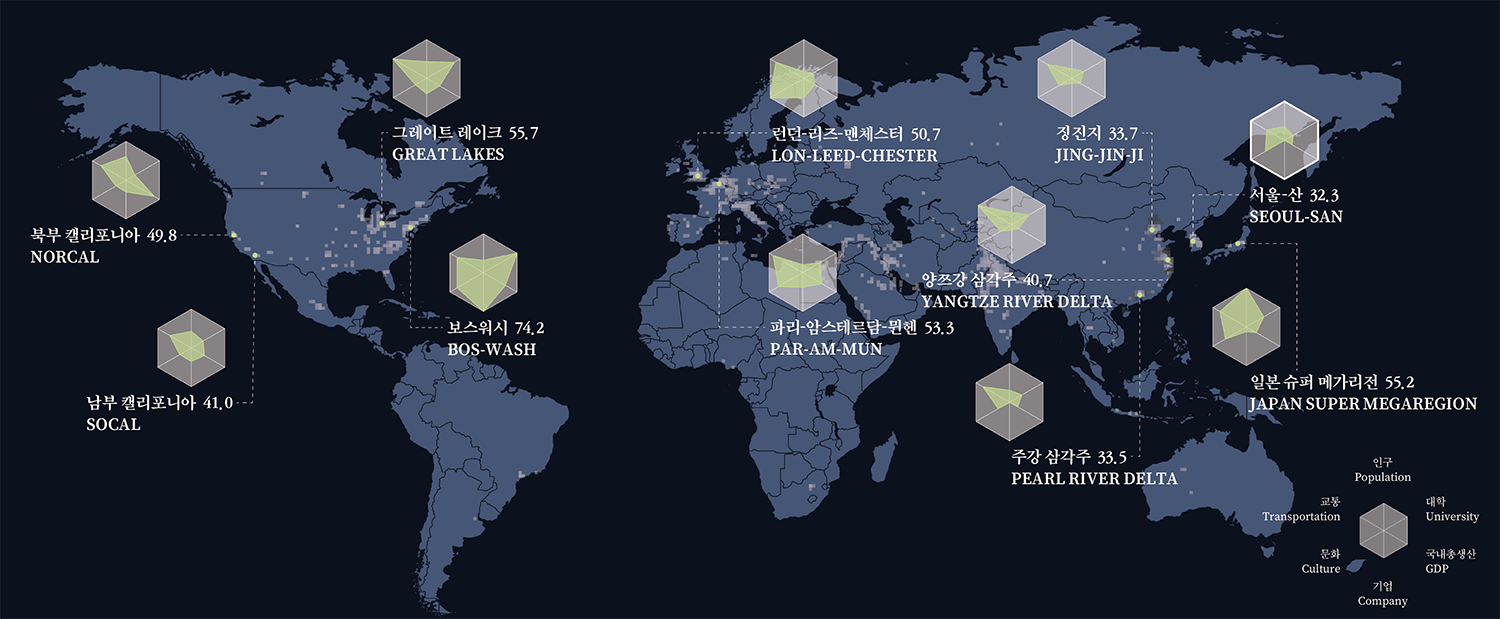

Index analysis for the world’s ten major megaregions and Seoul-San megaregion in Korea. To assess the relative capacity of the megaregions, we analyzed six indicators with radar charts: population, university, GDP, company, culture, and transportation.

The World’s Megaregions and Seoul-San of Korea

If one lists the top 10 largest cities in the world in the 1950s, one will see that they were all developed cities in the Northern Hemisphere, including New York, Tokyo, London, and Paris. However, a look at 2020 statistics shows that cities such as Mexico City and São Paulo in Latin America, Delhi and Mumbai in India, and Cairo in Africa have populations exceeding 20 million.▼5 The concentration of the population in the world’s largest cities results from urbanisation and globalisation. In recent years, cities, rather than countries, have become more directly involved in global networks, driving the global economy more powerfully than countries. In this context, the rise of ‘megaregions’, which form large urban and regional agglomerations, is emerging as essential to the future transformation of urban architecture.

A megaregion is the functionally connected space of a megacity, with a population of around 10 million, and its surrounding cities. Megaregions promote economic growth and innovation through economies of scale and the benefits of agglomeration, connect diverse cultures and resources, and achieve global competitiveness. They are urban spatial agglomerations that do not correspond to traditional administrative districts and have blurred and fluid spatial boundaries. In this sense, megaregions offer new hope. However, they are also where the problems of urban overcrowding and the disparity between rich and poor, the spread of infectious diseases and crime, and social division and conflict begin.▼6 Therefore, we need to look at the changing face of cities and the solutions to live more collaboratively together in the megaregions of the future.

Of interest is the work of Tim Gulden, Richard Florida, and Charlotta Mellander.▼7 Based on satellite imagery of continuous night-time light zones and a light-based regional product (LRP) of more than 100 billion USD, they found about 40 megaregions worldwide. Based on this, it is estimated that 1.2 billion people, or 18% of the world’s population, live in megaregions. These regions produce approximately 66% of global economic activity and 85% of patented innovations. Richard Florida argues that the world is no longer flat in his book The Rise of the Creative Class and an article in the Harvard Business Review. He says the world economy is shifting towards being run by a few megaregions rather than nation-states. The Boston-New York-Washington region of the United States, or Bos-Wash megaregion, has a population of 54 million and an LRP of 4.4 trillion USD, making it larger than France or the United Kingdom, according to CityLab’s 2019 ranking of combined country and megaregion economies. In its 2009 report, America 2050 Prospectus, the Regional Plan Association predicts that by 2050, megaregions will account for two-thirds of the United States population. Megaregions also play an essential role in Europe as the largest megaregion in Europe, the Paris-Amsterdam-Munich (Par-Am-Mun) region, has a population of 60 million and an economy with an LRP of 2.5 trillion USD, which is larger than the gross domestic product (GDP) of Canada. China is experiencing urbanisation at an unprecedented rate, and according to The Economist, the Jing-Jin-Ji megaregion in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region has a population of 120 million, the Yangtze River Delta megaregion in Shanghai-Nanjing-Hangzhou region has a population of 152 million, and the Pearl River Delta megaregion in Shenzhen-Guangzhou-Hong Kong region has a population of 60 million.▼8 More specifically, the Yangtze River Delta megaregion forms a substantial economic zone worth more than 2.2 trillion USD, exceeding the size of Italy’s economy. Japan has abolished its National Balanced Development Plan, implemented over 40 years from 1962 to 2000. Tokyo is still undergoing urban sprawl, with a population that exceeded 12 million in 2001, 13 million in 2010, and nearly 14 million in 2021. In this context, Japan is preparing a new Linear Chuo Shinkansen that will run from Tokyo to Nagoya and Osaka in 67 minutes and is planning to form a ʻJapan Super Megaregionʼ based on it.▼9

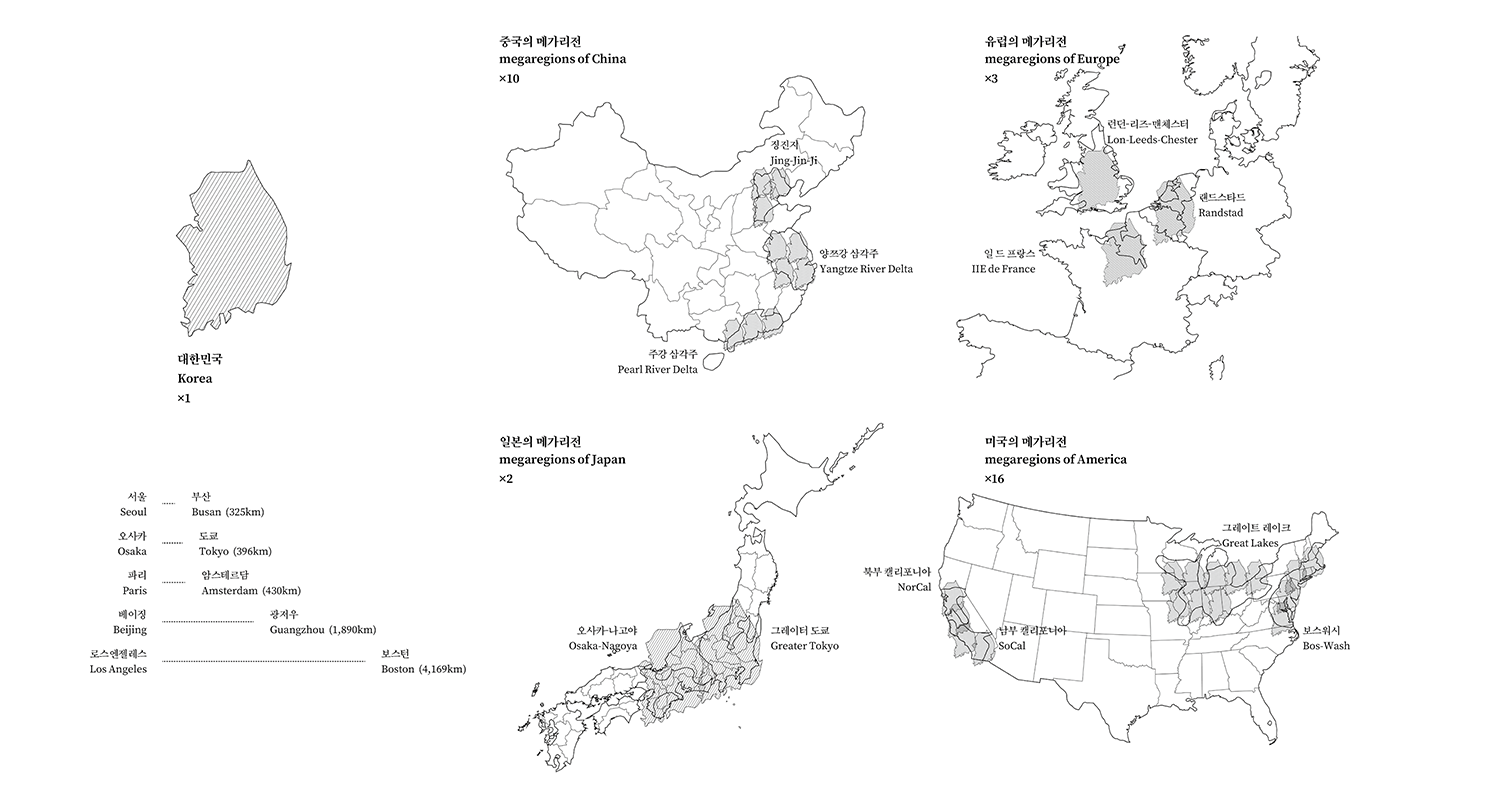

Comparing the physical size of Korea to the world’s ten major megaregions helps to give a sense of scale. Jing-Jin-Ji is three times the size of Korea, the Yangtze River Delta and Bos-Wash are four times the size, and the Great Lakes megaregion in the Chicago area is nearly eight times the size. Based on this, with a direct line of 325km between Seoul and Busan, it makes sense to look at Korea as a megaregion with the entire country as a major hub and with the ‘Seoul-San’ megacity as the central hub.

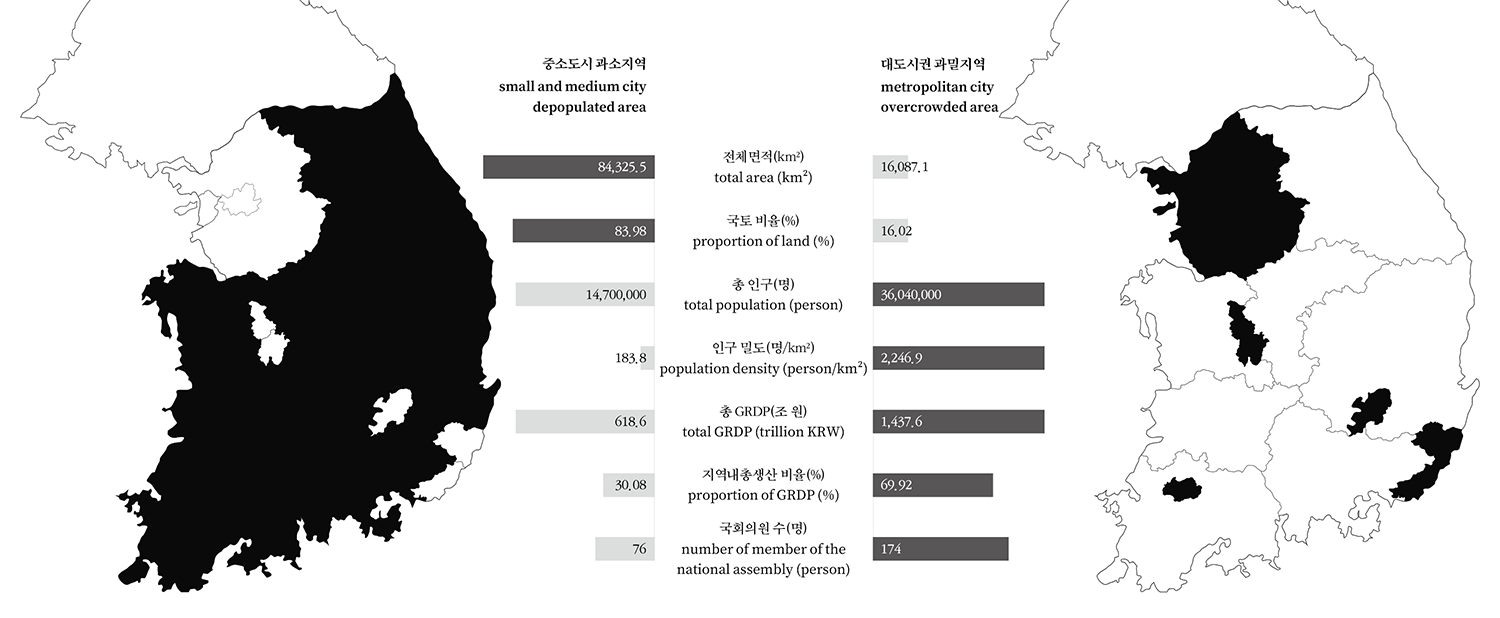

The disparities between depopulated and overcrowded areas in Korea

Future Transformation Strategy for Korea

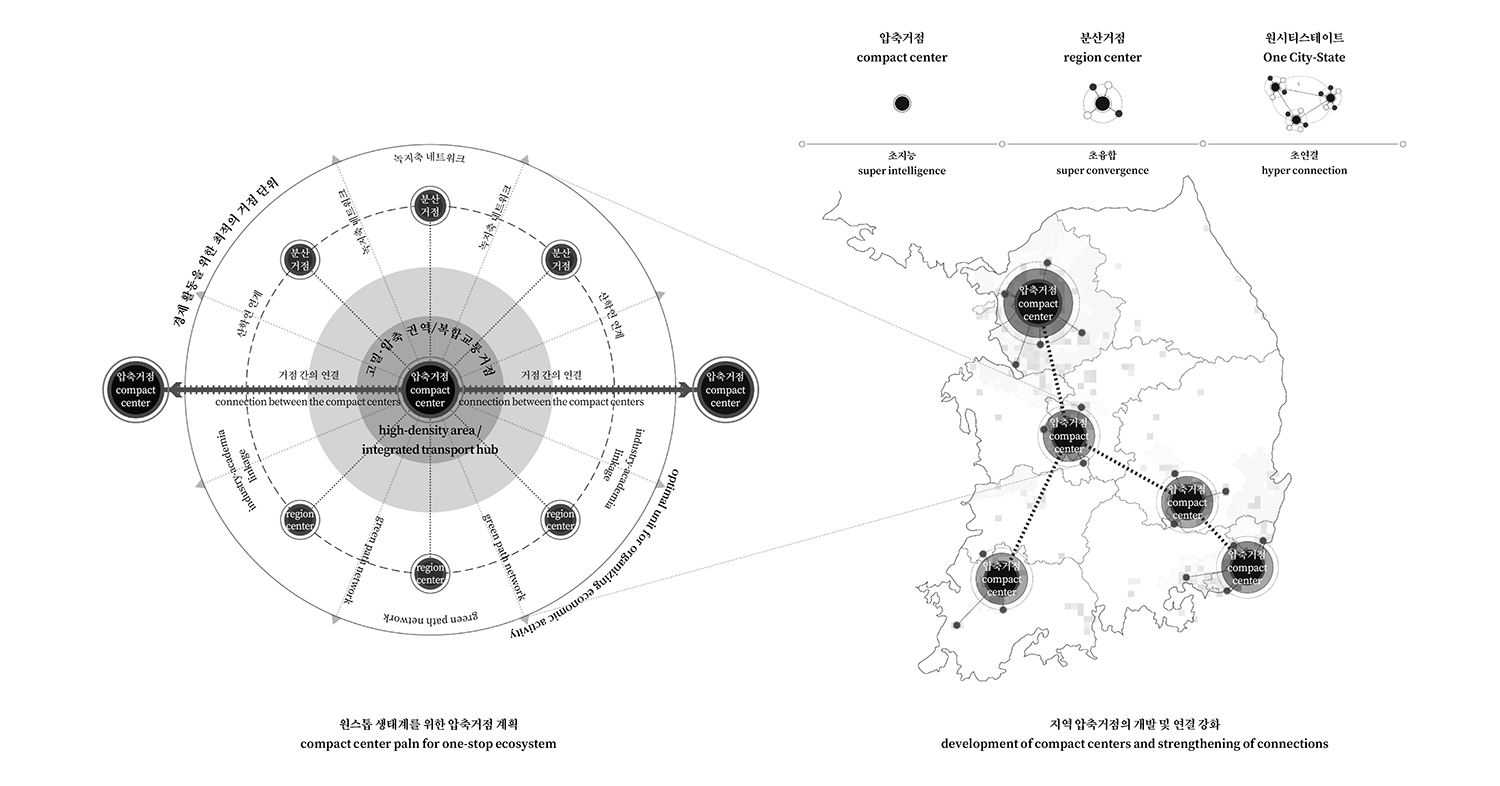

One of the biggest problems with the current geospatial landscape of Korea is the concentration of critical facilities in large cities and metropolitan areas, including jobs and entertainment. The population concentration in the metropolitan area is currently underway and accelerating because there is no such infrastructure and base in other regions except the metropolitan area. To solve this problem, we need a strategy to plan ‘compact center’ for jobs and entertainment in key areas of the country and to connect them with a high-speed transport network to unite the whole country. A compact center refers to a city with an innovation platform system whereby the city’s core programmes, such as work, education, medical care, shopping, and culture, can be integrated, and future trends such as low carbonisation, automation, and servitisation can be realised. Sustainable urban growth requires a synergy of industries, universities, and research institutions that can build essential infrastructure, transport, and compact center as ʻregion center’. To this end, the compact center should be built as a knowledge industry engine for cooperation between industry-academia-government, a contact point for intermodal transport, and the Seamless Integrated Mobility System (SIMS) for road, rail, and air transport.▼10

The so-called ‘straw effect’ concentrates population and goods in the metropolitan area and is accelerating because of the absence of appropriate compact centers. The long-term sustainable development of national space will be possible only by specialising the core industries of each region and securing jobs and entertainment centred on compact center and region center. When future transport modes such as the hyperloop are commercialised, the entire country will become a one-hour travel zone, creating a spatial effect of national pride, a ‘self-locating nation’ anywhere in the country.

In the case of Korea, the current trend suggests that by 2100 (unlike global population growth) its population is expected to decrease to 29.5 million, the level of 1966, and the elderly population is expected to increase relatively. To ensure sustainability in the face of decreasing population and available resources, the One City-State (OCS) can be proposed as the strategy. The primary strategy of the OCS is to operate Korea as a ‘city-state’ system by connecting the compact centers in each of these regions.

The disparities between the physical scale of Korea and the world’s megaregions. With a relatively short 325km direct-line distance between Seoul and Busan, it makes sense to view Korea as One City-State, with the entire country serving as a major hub, considering it as the ʻSeoul-Sanʼ megaregion.

Development of compact center and region center for building single hyper-megacity, One City-State

One City-State

OCS is the starting point for a MTP discourse that envisions the future of Korean urban architecture. As we face serious problems in contemporary society, such as population decline, ageing, and polarisation, it is necessary to reconstruct the entire national territory centred on compact centers in core regions such as the Seoul Capital Area, Chungcheong, Yeongnam and Honam areas. Furthermore, it is vital to consider the possibility of global connectivity with Japan, China, and Russia in the future. In other words, we need to prepare a strategy for future transformation by focusing on megaregions, mainly in the Seoul Capital Area, Chungcheong, Yeongnam and Honam areas, and connecting major compact centers with high-speed transportation networks to become a single hyper-megacity, OCS. It requires creative strategies such as reorganising the country’s transport network, expanding the administrative system, fostering the growth of specialised industries and attracting the knowledge class. Based on these ideas, three action directions for Korean future transformation were derived. The first is to establish inter-municipal governance to connect the entire country with regional compact centers. The second is to prepare a platform system of ‘super intelligence, super convergence, and hyper connection’. Finally, planning for geospatial should be a long-term process that transcends the five-year term of a government. OCS is a small but clear clue to the future of transformative urban architecture and the future of Korea.

Image of future city built centred on compact and region centers

Section diagram of a compact center where the city’s core programmes, such as work, education, and culture, can be integrated. We need a strategy to plan compact centers in key areas of the country and connect them with a high-speed transport network to unite the entire country.

1 Steven Kotler and Peter Diamandis, Abundance, Free Press, 2012.

2 Salim Ismail et al., Exponential Organizations, New York: Diversion Books, 2014.

3 United Nations (UN), World Population Prospects 2019, UN, 2019.

4 Ben Wilson, Metropolis, Doubleday, 2020.

5 It is based on a combination of statistical data in UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division and Statista.

6 Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis, Basic Books, 2017.

7 Richard Florida, Tim Gulden and Charlotta Mellander, ‘The Rise of the Mega-Region’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 1.3 (2008), pp. 459 – 476.

8 THE DATA TEAM, ‘Mammoth urban clusters are sprouting up all over China’, The Economist, 31 June 2018.

9 Lee Jaeyong, ‘Japan: Envisioning the Super Megaregion that the Linear Chuo Shinkansen will Create’, Planning and Policy, 485 (Mar. 2022).

10 John Moavenzadeh et al., Designing a Seamless Integrated Mobility System: A Manifesto for Transforming Passenger and Goods Mobility, Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2018.