SPACE August 2023 (No. 669)

Structure variation of LOSTONE

[CRITIQUE] Architecture of Primitive Rock: Objet Trouvé and Megalithic Architecture

‘I came upon one of those things washed ashore. It was the purest [of the whites], polished, hard, smooth, and gleaming. […] Who could have made you? I pondered. You appear to be nothing, but you are far from being formless. Are you a play of nature? O nameless being. Were you brought to me from the filth of this night sea by the gods?’▼1

Objet Trouvé

The mountain and rock in Seoul ©Jeong Euiyeob

Camouflage of Eroded Volcanic Stone

Recognising that the application of the found form is as significant as its selection, let us examine MELTING HOUSE. Is the house – located next to the coast – comprised of a concrete mass that resembles the rocks on the seashore a ‘duck’ type or similar to a ‘crab shell’? In terms of the entire shape’s enthusiastic interaction with nature through mimicking a rock, it seems to be similar to a ‘duck’ architecture; whereas, in terms of still emphasising spatial, tectonic, and structural art, it may be regarded akin to a ‘crab shell’ architecture. Strictly speaking, MELTING HOUSE is an irregular polyhedron and an abstracted form. It also has a framework system of intricate networks to transfer the load along the sides of the polyhedron. It deviates from the conventions of vertical and horizontal, and it implies a mystery by having interwoven diagonal lines. The building is clad with UHPC panels perforated with spots and stripes like eroded volcanic rocks. The so-called turing pattern is the result of a mathematical law that geometrically generates the patterns of animal skins and hairs that attempt to hide themselves from their natural environment. In terms of imitating the rocks on the seashore, which are the surrounding environment, it is employing architectural camouflage. Since it brings the exterior light and scenery into the interior, it evokes a military camouflaging membrane.In terms of camouflaging into nature, is MELTING HOUSE a contextual architecture? Since it is located at the point of contact between nature and the village, it is clearly contrasted with the surrounding architecture. Like how Bernard Huet’s 1986 article ‘L’architecture contre la ville’▼4 explained that architecture with a pursuit of ingenuity inevitably collides with conservative cities, architecture that approaches nature drifts away from the context of human civilisation and even displays a certain hostility to it. At this moment, it is natural to recall ‘Fuck Context’, which is one of the characteristics of ‘Bigness’ described by Rem Koolhaas.

The Generative Rule of Nature

MELTING HOUSE, which aims to return to the prehistoric period, incidentally resembles Casa da Musica and its archetype Y2K House by Koolhaas, who pursues metropolitan architecture. Koolhaas’ architectural projects are irregular polyhedrons that remind one of disparate objects from the surrounding context as well as a hunk of meteor fallen from space. In the case of Koolhaas, his projects did not only remain as a simple external imitation. Small polyhedrons of identical order are taken out from a single polyhedron, generating porosity. From a spatial perspective, the consistency between the whole and its parts is evident. In his 1876 work▼5, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc claims Mont Blanc as a single building or its ruin. He believed that the entire mountain had the texture of a crystal formation. He also explored the possibility of comparable architecture. Architecture resembling crystals should not remain as the ‘reproduction of plastic form’. It is desired that the architecture will be capable of having automatic growth in accordance with the ‘loi de la cristialisation (law of crystallisation)’ inherent in it. MELTING HOUSE also displays a form of porosity and provides a multilateral perceptual experience through the envelope and space. ‘Learning from a Stone’ gives rise to the expectation that one will be able to establish a kind of consistency that penetrates the entire space and structure. Of course, it is already not easy to build something by imitating the form of a rock. It is much more difficult to figure out the system that is ‘naturally’ realised in accordance with a natural law or material property. It is possible to materialise the space within a rocky cavern using concrete by insisting on the process of natural formation, like Truffle House by Ensemble Studio, although it can also be criticised for mimicking the happenstance of construction.

Concept sketch for MELTING HOUSE

MELTING HOUSE

Megalithism

In the 1960s Hans Hollein presented the simplest solution: build architecture out of actual, gigantic native rocks. He presented an architectural proposal that comprised a three-dimensional assembly of megaliths which was unrealistic that could only be realised by photomontage technique. It is something that can finally be imagined when it is based on the idea that architecture is, in essence, the construction of a monument that can be irrelevant to practicality and that whatever it uses, it is all architecture. Hollein’s solution can be accepted as a return to megalith architecture. A gigantic rock itself may simply be turned into a monument. This is attested by the first stone architecture from the prehistoric period. In his 1899 work, Histoire de l’architecture, Auguste Choisy explains as follows: ‘The first stone architecture shows the characteristic aspect referred to as mégalithisme. Architecture is comprised of a gigantic mass of rocks. Rather than the architecture of constructed masses of rocks, the architecture of simply transported masses of rocks preexist here and there.’▼6 Menhir and dolmen are distributed all over the world and have a similar appearance as if they were standardised architecture. The Korean Peninsula also served as a representative stronghold. Perhaps megalith architecture was an International Style that existed even in the prehistoric period. If the theory of primitive hut that questioned the origin and essence of architecture presented wooden architecture in the woods as the protagonist, the megalith architecture on the site was the very one thing that truly realised the permanent monument proclaiming the spirit of human community. The rock embodies the memory prior to the existence of humankind while, as an artificial landmark, it transforms the surrounding space into a sacred space.

Dom-Ino of Rocks

There have been sporadic architectural attempts to represent actual native rocks throughout the modern and contemporary periods. The Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright employed the native rock next to the waterfall as both the foundation and the floor of the fireplace in the living room. In Oscar Niemeyer’s Casa das Canoas, a single, sculpture-like three-dimensional rock penetrates the transparent façade and becomes the central element that connects the exterior and interior spaces. Like the aforementioned cases, LOSTONE internalises the exterior scenery through the arrangement of rocks. It selects a strategy that is slightly different from that of MELTING HOUSE. A towering building that is erected within the district of multi-unit houses in Daerim-dong is reminiscent of a gigantic menhir. According to the architect, the building was transformed and applied into a Dom-ino system, which supports the floor slabs with columns in the form of oddly shaped rocks. In every floor slab, oddly shaped rocks that resemble those in landscape paintings are stacked on top of each other. Unlike the Japanese traditional rock garden, which represents nature by reducing and reproducing it, the interior of LOSTONE aims to have the space and scenery of a milieu where human beings reside right in the middle of it. The visitors are drawn into appreciating the arts like a classical scholar inside a landscape painting, and also experience an awakening of their universal instincts as a primitive flâneur in the scenery of the menhirs in Carnac, Brittany, France. Not only do oddly shaped rocks protrude over the front windows, but the view from the inside also widens into a scene that strangely overlaps with the surrounding houses. The excavation of rocks is megalith architecture’s other method of construction that Choisy has also explained: ‘Mankind obtains solid metal tools and digs a hole in a rock cliff to make space.’▼7 Similar to the way primitive humankind set up dwellings by employing the winding surfaces of the rocks in rocky caverns, contemporary humankind also enjoys an outdoor life by making use of the nearby nature in a variety of ways, such as stepping, sitting, and lying down on the rocks. Similarly, the architect here presents how to appropriate the three-dimensional forms of LOSTONE’s primitive columns into bench, shelf, or planter. Thus, each column of oddly shaped rocks becomes a reduced architecture.

Complexity of the Transformed Structure

The columns of oddly shaped rocks at LOSTONE are concrete masses, and they were also realised through an additional, secondary cast-in-situ after the framework of each floor was cast in situ. This may raise criticism of its tectonic economic feasibility, and it may be considered as simple ornamentation that ends up adding unnecessary weight to the actual vertical columns. However, isn’t it the weightiness, which is considered excessive in terms of contemporary structural mechanics, that is a characteristic and even essence of the megalith architecture? It is the same for the heavy tiled roof of Korean tradition. The hipped and gable roof of Muryangsujeon Hall at Buseoksa Temple is gigantic and massive as it recalls the horizontal monolith of dolmen. In virtue of that, a sublime and grand sight floating in the air is created. The excessiveness of the roof makes the entasis column more streamlined. The vertical columns of LOSTONE are physically settled to a concrete mass of oddly shaped rocks and have an unnatural thickness. To follow the right to light, some corner columns are even slanted. The structural role of thick and slanted columns becomes unclear. The ambiguity and complexity are aggravated thus becoming abstruse. Simultaneously, its effect as an organic mass is enhanced. The structure that is unnecessary in a specific situation leaves room to respond in an unspecific, different situation. In that way, the unity as a unitary object is heightened—just like a rock, as an autonomous structure that still responds to gravity, even when it is laid down, erected, or turned upside down. As the pure orthogonal system of structure is transformed, the statics network that was used to distribute the load into vertical and horizontal directions collapses, and the new structure becomes close to an entangled skein of thread or weaving, or a Jenga in a state of intricate balance that is being dismantled through a game. It is the same for the structure of the dolmen. While each weight is leaned on, each element is slanted to tolerate the load, resulting in a state of non-computable balance. The final form is accepted as a result. Like the first-touch in the domino effect, it is a process of unknown series of balancing that is at last activated after the final megalith is put on. The weightiness suppresses each element, resulting in dynamic stability. Wouldn’t the structural characteristics of a stone tower that Koreans build with small pebbles at a stream beside a mountain temple be comparable to this? The conceptual model of LOSTONE is akin to people’s playing of building a stone tower. Apart from the tectonic truth, this is what the ideal model of the structure that LOSTONE seeks is really like.

Process of re-integrated structure of LOSTONE

LOSTONE

Abstracted Megalith

Unlike MELTING HOUSE or LOSTONE, METABOX in Yangpyeong has a regular form. Nonetheless, METABOX is also – only just an abstracted version of – a primitive architecture that is reminiscent of a gigantic rock. When it came time to design a single building that needs to provide archiving and exhibition spaces for the client, artist Suh Yongsun, as well as a separate space for humanities and arts publication to move in, the architect strived to conceive architecture that resonated with the artist’s art.He decided to directly employ the characteristics of plane-like three-dimensionality or the sense of three-dimensional plane that are frequently found in the spatial representation of the artist’s paintings. A three-dimensional spatial expression is reminiscent of an axonometric technique of a parallel projection, which is a quite familiar architectural expression technique in addition to perspectives. However, in the artist’s work, each space or building is not integrated into a single order, and similar to paintings prior to the law of perspective, each shows an autonomous and individual three-dimensional effect. Each space appears to be expressed realistically, yet when viewed as an overall composition, it does not hide from being fictional. It is the coexistence of the reality of the pictorial plane and the fabrication of architectural three-dimension. If it was necessary to create a parallelepiped in axonometric paintings to make oneself aware of the illusion of a cuboid, then, similarly, METABOX realised a parallelepiped as it is in real space triggers a unique phenomenon of recognition of a constantly varying cuboid. In general, a sense of reality in trompe-l’œil is available from a single and sole viewpoint. However, METABOX, which three-dimensionalised a two-dimensional pictorial drawing, generates a three-dimensional perception that appears to be always realistic. The three-dimensionality gradually changes every moment. Even more so, at one point, METABOX appears as a two-dimensional surface, even when viewed diagonally from the corner rather than from the front. Such a cognitive experience continues to trigger the observer’s interest and gives a stimulus not to stop but to move around.

Architecturised Monochrome

Views of making colour for METABOX with artist Suh Yongsun ©Jeong Euiyeob

Multiple vanishing points

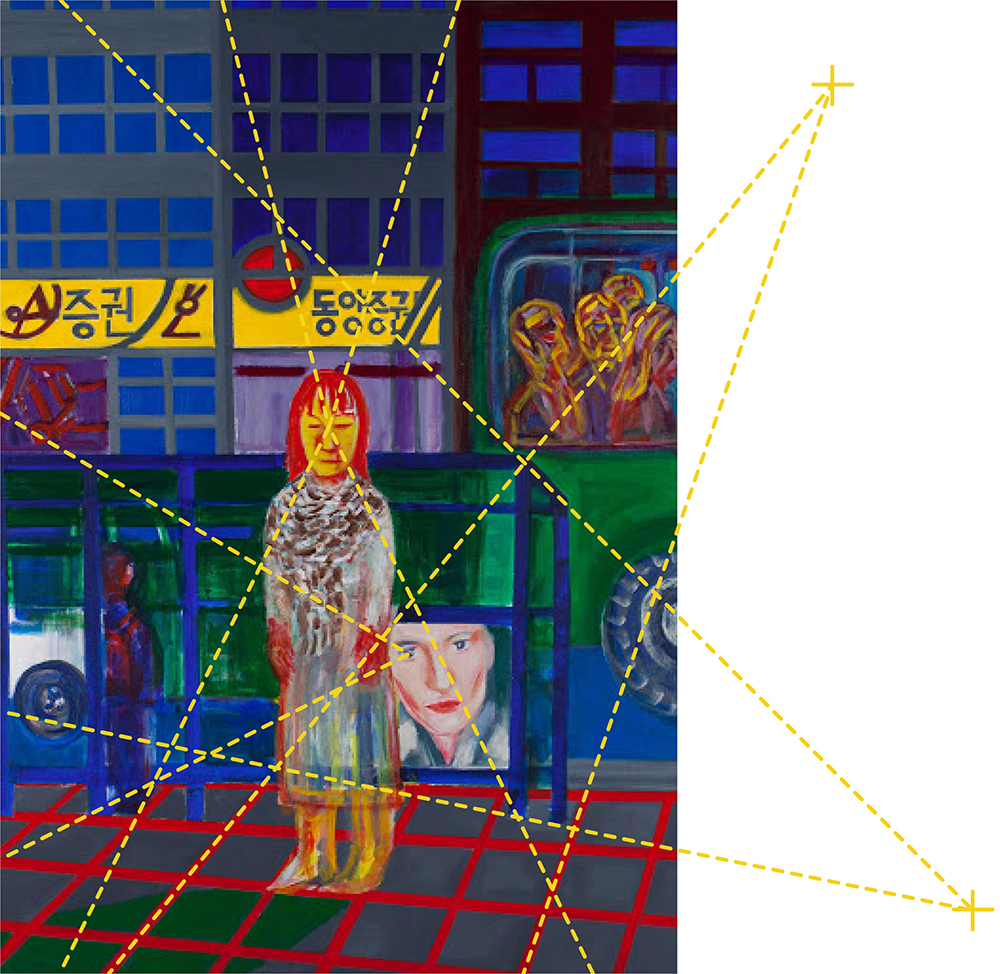

Suh Yongsun, Yeoksam Station 1, Acrylic on canvas, 160.3×114.5cm, 2015 / Image courtesy of SuhYongsun Archive / edited by Jeong Euiyeob

1 Paul Valéry, Eupalinos ou l’Architecte (1921), Paris, 1970, p. 65 (Jacques Lucan, cited, p. 188).

2 Tim Benton, LC FOTO: Le Corbusier Secret Photographer, Lars Müller, 2013, p. 307.

3 Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète 1957 – 1965, pp. 80, 91, 107.

4 Bernard Huet, ‘L’architecture contre la ville’, AMC 114 (Dec. 1986).

5 Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Le Massif du Mont Blanc, 1876.

6 Auguste Choisy, Histoire de l’architecture, 1899, pp. 3 – 4. Translated by Nam Sungtaeg.

7 Ibid, p. 6.

8 Robert Morris, ‘Notes on Sculpture: Part 2’, Artforum, Oct. 1966, qtd. in Claude Gintz (éd.), Regards sur l’art américain des années soixante, Paris : Éditions Territoires, 1988 (1979), pp. 87 – 88.

You can see more information on the SPACE No. 669 (August 2023).