SPACE September 2023 (No. 670)

Can textiles be a building material? Textiles of flexible and lightweight properties have long been disregarded as materials for construction at the opposite point of solid and fixed architecture. Moriyama Akane (principal, Studio Akane Moriyama), who majored in architecture and textiles, has tried to make interventions into the architecture and space through textiles, noting that textiles can be another way of constructing architecture, not just an interior element. SPACE asked Moriyama – who realise the spaces on various scales often using a single layer of fabric and sometimes a volume through layers of fabric – about the potential of textiles as a building material and the use in developing a new construction method.

Interview Moriyama Akane principal, Studio Akane Moriyama × Kim Jia

Kim Jia (Kim): Unlike solid and sturdy building materials such as concrete, glass, brick, and metal, textiles have been excluded or at best considered subordinate to these other options. What drew your attention to textiles?

Moriyama Akane (Moriyama): Since childhood, I have been interested in space, so I studied architecture. I noticed the potential of textiles as a material for architecture during the process of establishing my own design language while working in the field following graduation. We could create many diverse fabrics by choosing different kinds of fibre, applying different spinning techniques, questioning how we form structures (for example weaving, knitting, knotting), as well as exploring a wide range of dyes and prints. For example, if thousands of layers of fabric are drooped, it is no longer a single piece of fabric, but a three-dimensional volume that can become a wall, ceiling, or floor in itself. Humankind has long developed a vast storehouse of knowledge about textiles. However, the use of textiles in architecture has been limited to traditional methods for a long time. My brief is that more considerd use as a design intervention can shift the boundaries that presently exist between architecture, landscaping, and art.

Kim: Why do you work mainly on curtains or partitions?

Moriyama: For me, applying curtains to architecture offer a simple and fun gesture that becomes an integral part of the space. Compared to floor rugs and furniture covers, curtains have room to intervene more actively in space based on their flexible characteristics. A piece of fabric can change a space dramatically. Since every location has different context, every project is an adventure through which one reveals the hidden qualities of the space.

Installation view of Curtain for O House (2009). The largecurtain for the façade covers a window of W2 × H7.1m, this to ensure the privacy of the residents and also insulate the window further against cold air. / ©Takumi Ota

Installation view of Curtain for O House (2009). The largecurtain for the façade covers a window of W2 × H7.1m, this to ensure the privacy of the residents and also insulate the window further against cold air. / ©Takumi Ota

Kim: Since your first commissioned work Curtain for O House (2009), you have designed curtains for various spaces including homes, churches, schools, and offices. Across many of your projects, the curtains actively and mutually interact with the architecture and space, and go beyond their basic functions such as doors, a dividers, or screens for blocking out sunlight. Do you think that curtains can replace or complement more commonly-used and sturdier architectural elements? (e.g., walls, columns, ceilings, floors, and roofs)

Moriyama: I believe that the application of textiles in an architectural context has the potential to dismantle preconceived ideas the very nature of key architectural elements. For example, with textiles we can create a ‘wall’ that is at once soft and transparent but also thick, though I don’t know if it can be known called a ‘wall’ since it might not be load-bearing. I don’t expect textiles to replace those existing ‘hard’ architectural elements since they also have their own material characteristics which textiles cannot replace. However, textiles can propose new perspectives towards our existing conception of architectural elements. They are easy to transport, versatile in terms of play with colour and pattern, and can be also used on small to large scales.

Kim: Noting the global trend towards lighter buildings (saving resources, reducing carbon emission, increasing variability), there is an increasing interest in textiles as an architectural material. What is your view on this?

Moriyama: Certainly, textiles can help to reduce the environmental burden buildings. However, we need to consider the life of textiles in the long term. What will happen to millions of metres of fire-retardant polyester curtains in hotels after 30 years? It’s a challenging question since we live and work in the realities of capitalistic world. But even though I am but one tiny part of the wider industry, I am looking for the answer and trying to find a way of circulating our approach and system with greater wisdom.

Kim: If we consider curtains to be in the realm of space design, then they become more like intervening in a constructed space ex post facto. What is the potential and limit of this approach in terms of their range and applicability?

Moriyama: When I work with architects, I always try to avoiding joining the post- construction phase. I try to avoid last- minute projects. This is because if I am able to participate a project from the early stage of a building plan, I can propose bold design ideas that accommodate the intervention of textiles. For example, instead of building a heavy wall we could consider the option of textile walls. If I’m joining the project in the final hour of the construction period, quite often it’s more difficult to integrate this work—less flexibility, less time, and limited budget.

Installation view of Curtains for Blue House (2021). In a house in Shizuoka, Japan, curtains installed in layers instead of walls are used as elements to divide the space. / ⓒKenta Hasegawa

Installation view of Curtains for Blue House (2021). In a house in Shizuoka, Japan, curtains installed in layers instead of walls are used as elements to divide the space. / ⓒKenta Hasegawa

Kim: It is not common to have included a design process or element involving textiles at the initial stage of a project. I am curious about your approach to collaborating with architects.

Moriyama: Perhaps it is not common that textile works are involved in early stage of the project in Europe or Japan as well as Korea, especially in interior projects. I’m lucky to work with architects / clients who are courageous and contact me at the early stages of sketching out a project. We often start by sharing plans, models, and ideas to start a conversation. Then we begin exchanging sketches and fabric samples. Sometimes we cannot meet frequently face to face, but we always try to check the fabric samples on a small scale to a larger scale under similar light condition to the final setting. This is because fabrics appear quite differently depending on their location.

Kim: Do you approach work differently depending on whether your client is an architect or building owner?

Moriyama: I work and communicate with the clients in quite simple manner. I try to propose clear ideas to anyone who is in the same boat so that everyone can share and aim for the same direction. In that sense, clients are one of the members to achieve the goals as well as the other member of the boat, like sewing persons, builder, architects, structural engineer.

Kim: I am informed that you put yourself in charge of everything from design to production. To put it in architectural terms, it would be like doing everything from design to construction.

Moriyama: At present, my studio consists of myself, but sometimes there are assistants and collaborators here too. Since I am mainly active in Japan and Sweden, I have a longstanding relationship with textile workers in Japan and Sweden, and I really appreciate their level of professionalism. My collaborators always offer great advice about how to make, install, and transport the works. Without their help and regular conversations with them, I cannot go forward with the project. In design, as in architecture, I sketch, set dimensions, and draw drawings. However, it is different from architecture in that it is possible to experiment with materials at the studio level and directly implement small-scale works.

Kim: You continue to experiment with various fabrics using dyeing, printing, and weaving. Compared to architecture, what do you think is the charm of textile work?

Moriyama: Dyeing is a chemical reaction of the molecules, and weaving is mathematical thinking. Even though I am not very good at both fields, I could work with this material since there is somehow a fuzziness in textile. A piece of fabric stretches and shrinks. Every natural fiber has different qualities. There is always a surprise during dyeing process. We cannot draw the shape of fabric exactly since it is transformed by gravity. For me, this uncontrollable state of textile is exciting aspect.

Dyeing process of textile. Aside from its physical functions (insulating sound, blocking sunlight, partitioning space), textiles also have emotional functions in relation to the visual and tactile experiences that they provide. Studio Akane Moriyama’s work especially amplifies such functions by emphasizing color and texture.

Dyeing process of textile. Aside from its physical functions (insulating sound, blocking sunlight, partitioning space), textiles also have emotional functions in relation to the visual and tactile experiences that they provide. Studio Akane Moriyama’s work especially amplifies such functions by emphasizing color and texture.

Kim: Based in Stockholm, the project continues in various countries such as Japan, Sweden, and the U.S.. Is there a point where the work differs depending on the region, culture and climate?

Moriyama: For example, when it comes to residential projects, keeping privacy is one of most important factors in Japan, while I feel people care more about atmosphere than privacy in Sweden. Also, natural light influences the choice of the colour. In Sweden where the latitude is higher than Japan, we tend to choose subtle colours because of special nuances of colour in Nordic landscape.

Kim: You use various materials (such as cotton, linen, wool, nylon, silk) and colours between differing contexts to create disparities in terms of light, texture, and ambience. While it might differ per project, what kind of spatial experience do you hope to achieve through your designs?

Moriyama: I would like people to feel the spaces through their own senses. Sensing breeze, lighting, colour, and texture are simple pleasures in which everyone can share without the need for verbal communication. I remember vividly the moment when I saw drift-ice at Hokkaido when I was a student. The scale, the sound of drift-ice crushing, how time passes… It was unforgettable moment that forced me to reckon with the fact that I had been living in such a small area of the earth. I hope textile interventions while help others to experience such moments.

Kim: Aside from commissions, you have also created art installations using textiles. While Mirage in the Forest (2016) captures a sense ofthe flow of time by responding to the movements of the invisible wind and living organisms in the forest, Azorean Spectrum Range (2017) cuts across a museum’s inner courtyard to embody your reflections on the nature of public space and locationality. How do you hope to intervene in urban spaces through textiles? What kind of experiences and messages do you ultimately want to convey through your work?

Moriyama: When I worked on the installation project at 12632g at Sergels Torg, a central square in Stockholm, these sentences from Gertrude Stein were in my mind: ‘After all anybody is as the sky is low and high, the air heavy or clear and anybody is as there is wind or no wind there. It is that which makes them and the arts they make and the work they do and the way they eat and the way they drink the way they learn and everything.’ When placing the fabric, I wanted to visualise the air in the square, believing it would be meaningful for some of the viewers to witness the movement of the air in which you stand and breathe. Because, according to Gertrude Stein, that shapes the everything of life. People passing through the square might accidentally encounter a visualisation of the shifting air currents through the movement of the fabric. The fabric is a kind of intervention between people and something people usually don’t pay attention to in daily life.

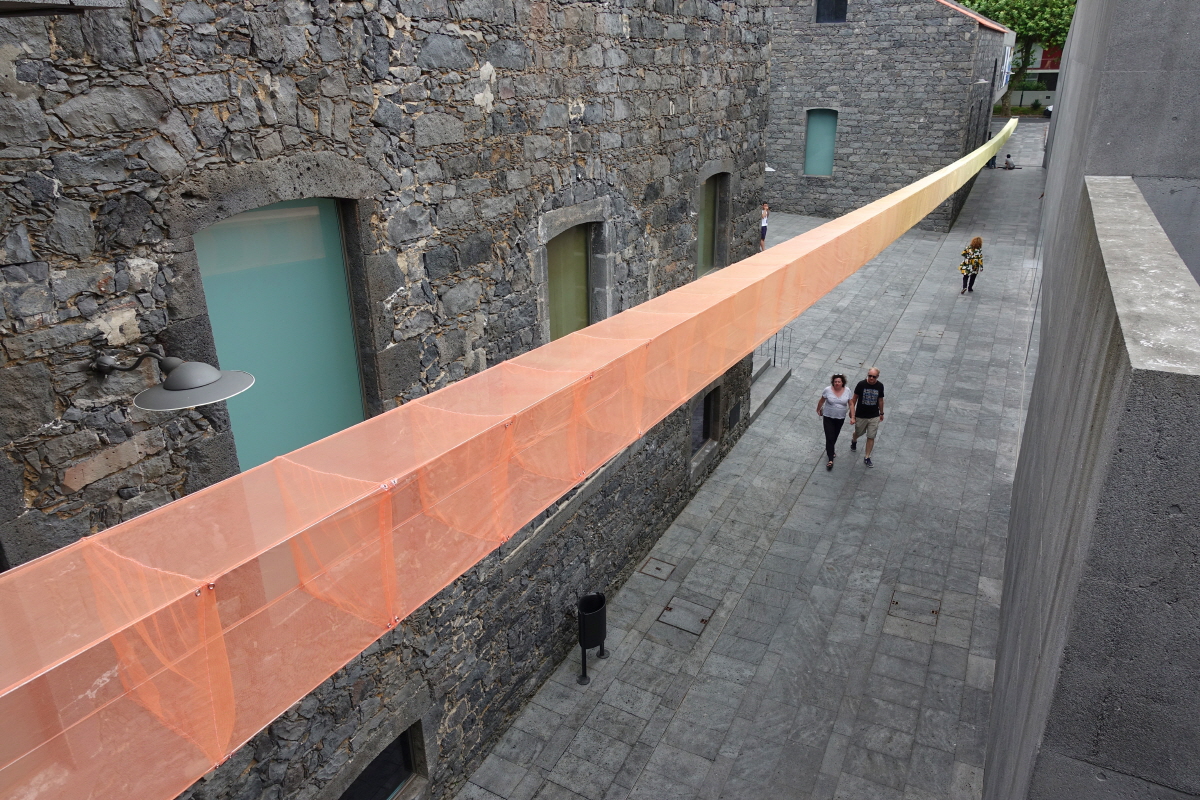

Installation view of Azorean Spectrum Range (2017). The work installed in the central courtyard of the Arquipélago Contemporary Arts Centre, Azores, Portugal, extend the interpretation of territory by decentralizing the artistic action. The long structure gradually transforms from one colour to another, changing in appearance as visitors move across the space, creating a new sense and perception of scale.

Installation view of Azorean Spectrum Range (2017). The work installed in the central courtyard of the Arquipélago Contemporary Arts Centre, Azores, Portugal, extend the interpretation of territory by decentralizing the artistic action. The long structure gradually transforms from one colour to another, changing in appearance as visitors move across the space, creating a new sense and perception of scale.

Kim: You showcased a Textile Roof as part of the Japanese Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale. Based on the awning and ceiling louver that Yosizaka Takamasa – being inspired by the Venetian light and shadow – had designed for the Japanese Pavilion, you created a light and flexible structure made of recyclable polyester cloth. Instead of being pointed upward like a typical roof or canopy, the roof has been stretched out alongside the trees at a relatively low height. Why did you opt for this form?

Moriyama: Through the fabrics, we wanted to highlight a path towards the entrance of the pavilion. When you go up the stairs towards the garden, you gradually approach a lower ceiling and cosier atmosphere beneath the roof. And then you ascend a few steps to reach the building’s entrance. Similar to the approach to a tea house in a Japanese garden, visitors can sit beneath the roof before the exhibition and then step into the small entrance to the room. We designed it to be a part of the experience of walking through the pavilion.

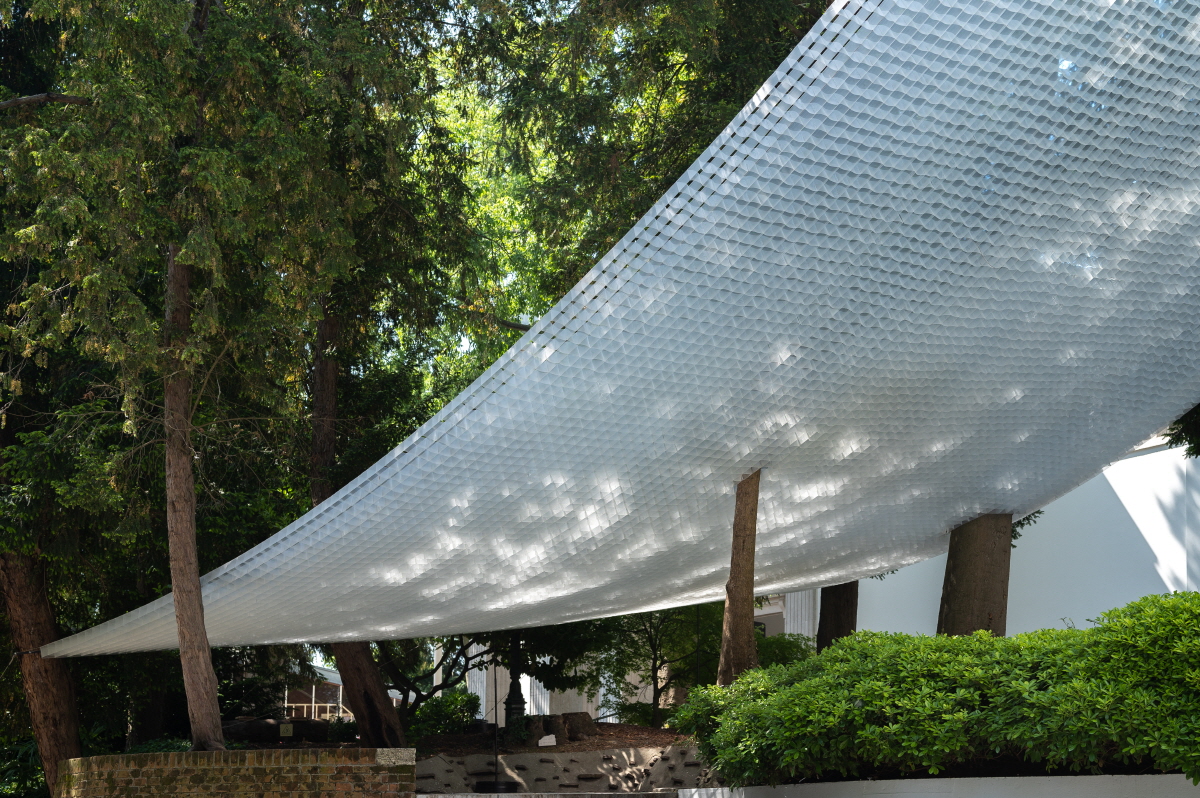

Installation view of Textile Roof (2023). The roof installed at the Japanese Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale is based on the awning and ceiling louver that the architect Yosizaka Takamasa – being inspired by the Venetian light and shadow – had designed for the Japanese Pavilion

Installation view of Textile Roof (2023). The roof installed at the Japanese Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Biennale is based on the awning and ceiling louver that the architect Yosizaka Takamasa – being inspired by the Venetian light and shadow – had designed for the Japanese Pavilion

Kim: Instead of just using a single layer, the roof is composed of multiple layers of fabric in a three-dimensional lattice structure. What functional purpose does this serve? Please elaborate as fully as you can on how this design (e.g., size and dimension) came to be.

Moriyama: The Textile Roof is made of a layer of three-dimensionally woven fabric. The layer consists of 100㎡ of grids with 100mm-wide recycled polyester sewn by hand. We needed to create a flexible roof which would be able to withstand heavy rain and gusty winds like the sirocco for at least a half year. The grid structure allows the wind and rains to permeate through while also offering a dynamic and varied appearance depending on where you are viewing it. The structure is hanged with 76 fluorocarbon fishing lines woven into the fabric. There are no metal wires nor hard structures within the fabric. Since it was flexible and light, we brought it via our hand luggage allowance from Japan! We tried not to manipulate the fabric shape since it needs gravity to make the form. It was a result of a fruitful collaboration with structural engineer, textile workers, architects, weavers, and a craftsman. What we really cared for on site was its relation to the existing trees at the garden. We did not want to risk any damage to the trees since the trees are so precious in Venice. The exhibition at the biennale changes every year, but the trees stand there always.

Textile Roof is made of a layer of three-dimensionally woven fabric. The layer consists of 100㎡of grids with 100mm-wide recycled polyester sewn by hand. / ⓒSandro Sulaberidze

Textile Roof is made of a layer of three-dimensionally woven fabric. The layer consists of 100㎡of grids with 100mm-wide recycled polyester sewn by hand. / ⓒSandro Sulaberidze