SPACE June 2023 (No. 667)

Mataaho Collective, Tuakirikiri, Polyester webbing, Installation, Dimensions variable, 2023

The 14th Gwangju Biennale opened on the 7th of April. As the largest art festival in Asia, the works of 79 participating artists from Korea and around the world flooded into the city of Gwangju. Organised by artistic director Sook-Kyung Lee, the theme of the biennale is ‘Soft and Weak like Water’, borrowed from Dao De Jing. The biennale refuses to take on big city-wide events or showcase spectacles but prefers to observe the slow percolation of art in the environment, an approach to art that embraces and permeates the streets like water and symbolises its transformative and restorative potential. When humanity is once again calling upon the power of art to help mitigate the effects of times of crisis and pandemic, the cries of resistance and solidarity must begin to ring out across the world. Here, SPACE reviews the planning, strategy, and direction of the biennale, which is expanding into ever more diverse directions with its nine national pavilions.

Pangrok Sulap, Gwangju Blooming series, Woodblock print on fabric, 2023, The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission

Aliza Nisenbaum, Shin-myeong, Installation view, 2023, The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission / Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

Gwangju Again

It was early May when I visited Gwangju. Gwangju in May, with an animation different to the excitement of the opening, tends to recall the historical events of 40 years ago. A one-person protest calling for the abolition of the Park Seo-Bo Art Prize stood out at the entrance of the exhibition. What does it mean to be ‘Gwangju again’, in a place where the biennale’s theme of ‘a place for experimental discourse’ has been questioned, and where there has been widespread criticism of the selection of the theme and its participating artists? What new pathway can be proposed to reimagine the ‘Gwangju spirit’ rooted in a notion of the people’s resistance, when this event is under the implicit constraints of being consumed as part of a city brand and political image?

Sook-Kyung Lee proposes a ‘planetary viewpoint’ that regards ‘humanity as a species and a global community’ as a strategy for bringing these complex situations and issues together. Her practice and experience as senior curator of international art (Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational) at the Tate Modern, where she researched artists from the developing world, can be summarised in the term ‘transnational curating’, which includes non-Western perspectives. She identifies the source of the Gwangju spirit as pluralism and attempts to ‘move away from the binary structure that divides the world into center and periphery and view it from points of intersection and connection distributed across time and space.’ By harnessing the power of art like water that embraces division and difference, she intends to imagine our shared planet as a site of resistance, coexistence, solidarity, and care.

The exhibition is organised around the practices of artists that have responded to global crises under four subthemes: Luminous Halo, a message of solidarity with pro-democracy movements and resistance to discrimination and inequality; Ancestral Voices, a challenge to Western modernity through indigenous peoples and traditions; Transient Sovereignty, an artistic practice that promotes diasporic and postcolonial thinking; Planetary Times, a call for coexistence in the face of environmental and ecological crises. The selection of these themes can be seen as a methodology for bringing together otherness, which has been marginalised by capitalism and modernism, across time and space, borders and cultures, which are reflected by the spectrum of participating artists. More than 80 artists from 30 countries transcend generational, gender, racial, and indigenous boundaries in time and space. They have one thing in common in that they have a long history of immersing themselves in their cultural traditions and histories.

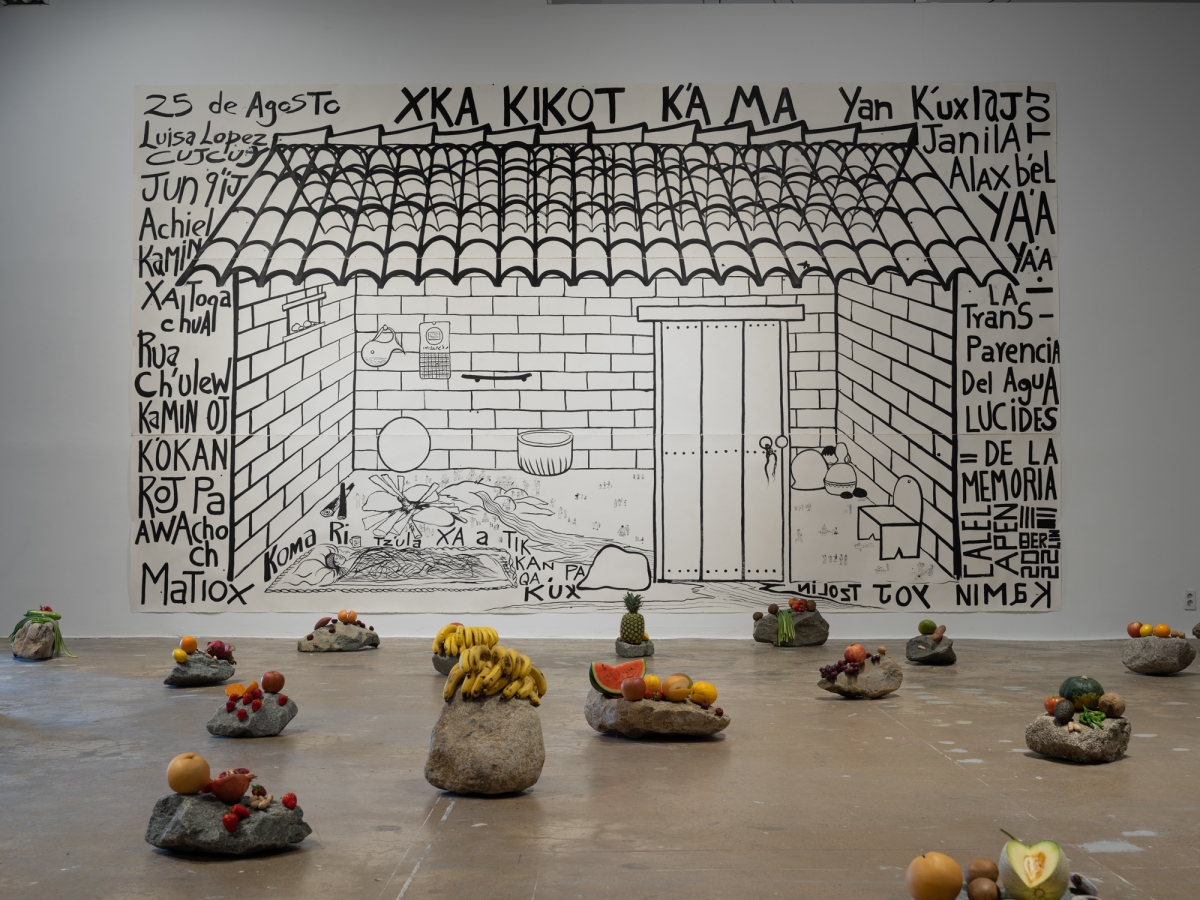

It is also noteworthy that this biennale took a commission system to overcome the limitations of existing exhibitions on non-Western traditional cultures which have failed to resonate with our reality. In this curatorial endeavor, Ancestral Voices clearly conveys the intersection of traditions from various cultures, including Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Immersed in traditional crafts such as palm leaf weaving and incense, the Taiwanese artist Charwei Tsai burns spiral incense sticks inscribed with the words of the Heart Sutra and represents the moment when they turn to smoke and ash to reveal the essence of the Eastern spirit in the exhibition. Bakhyt Bubikanova from Kazakhstan explores the style of traditional Oriental Miniatures from the Central Asian region, challenging tradition and creating new interpretations by erasing key parts of her paintings. Edgar Calel, a member of the indigenous Kaqchikel tribe of Guatemala, also draws on tradition including tribal mythology and totemism as a source of inspiration in her installation work. The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge (2023), which transforms the exhibition space into a ritualized site of giving thanks to ancestors, connects our culture with indigenous cultures through a ‘ritualized ceremony’. The artists draw upon the histories and traditions of the former inhabitants who used to be considered uncivilised as creative seeds to expand their critical thinking about the realities long engulfed by Western modernity, so as to further broaden the horizons of our perceptions of ritual and tradition.

Edgar Calel, The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge, Installation mixed media on the floor, Dimensions variable, 2023, The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission; Here are the elves that you left seeded in our hearts, Mixed media on wall, Dimensions variable, 2023, The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission / Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

Bakhyt Bubikanova, Ferdowsi’s Poem series, Acrylic on canvas, 110×70cm, 2019

Site-specificity and Materiality in the Biennale

Given the increase in the number of bienniales, Hans Ulrich Albrist pointed out that ‘exhibitions have the challenge of offering new spaces and new temporalities’. Okwu Enweiser, the artistic director of the Gwangju Biennale in 2008, also noted at the time that ‘exhibitions are a medium which has a narrative structure that is viewed over a period of time.’ This suggests that the connection and flow between works is an important issue in exhibition planning, not only for site-specific works. In this regard, this biennale stands out in that it has changed the flow and layout of the exhibition hall. The exhibition will begin at the conventional exit and end at the entrance, which means that the biennale starts from Exhibition Hall 1 with its low floor height. The artistic director may have decided on this deliberately, as An Offering (2023), Buhlebezwe Siwani’s work installed in this long and low ceilinged space, marks an apt first impression of the biennale’s theme of the ‘fluid imagination’. Transforming the venue into a forest of earth, wooden pillars, and knots, the South African-born artist installed a giant fish tank in the centre of the room and projected images onto its surface. The installation implies indigenous traditional cultural beliefs (a matriarchal society) in the healing and restorative energies of nature, forming a preface to the exhibition’s four subthemes.

The circulation along the ramp reveals that the exhibits are sparsely arranged throughout the exhibition. The number of artworks is reduced, and chairs have been placed here and there for convenience. The interior with more room physically and visually, provides visitors with time to meditate and contemplate as they move from piece to piece. Luminous Halo delivers a narrative flow that expands on this message through the juxtapositions and connections between the works. The Malaysian collective Pangrok Sulap researched the activities of woodblock printmakers during the May 18 Uprising and created Gwangju Blooming (2023), a hanging print of mothers distributing rice balls to the civilian army, which reads and visually resonates with Oh Yoon’s print placed behind it. Oh Yoon’s sense of subject, which tries to express the reality of a people and the resentment of history through shin-myeong, continues with Aliza Nisenbaum’s Shin-myeong (2023), which is placed right next to it. The artist, who has filmed many interactions with the community painted the yard play of Shin-myeong, a local theatre group organised in Gwangju after the May 18 Uprising and active for over 40 years. The commissioned works of the two foreign artists reinterpret Gwangju spirit and pay homage to it, deepening the viewer’s understanding and resonating with their aims.

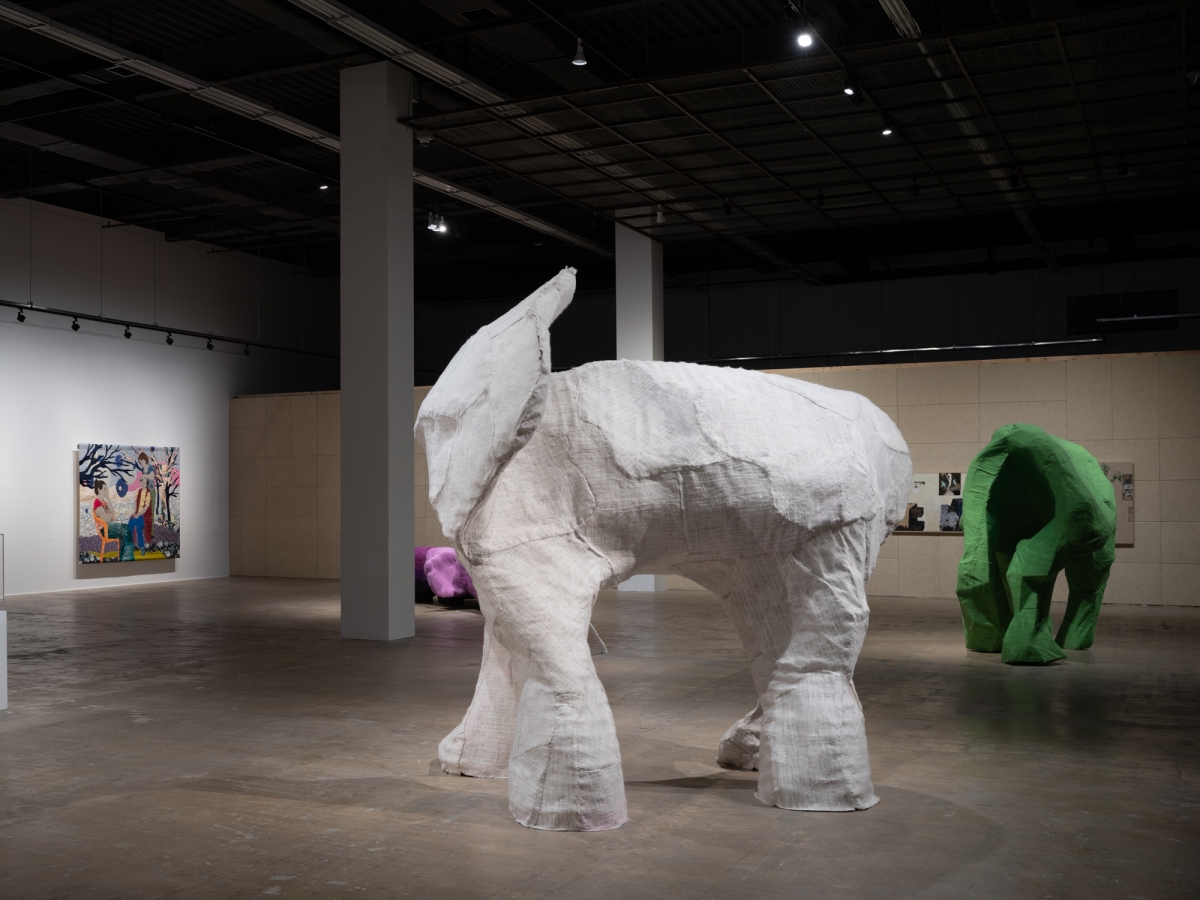

Meanwhile, the works of Oum Jeongsoon, Christine Sun Kim, Soun-Gui Kim, located at the end of Room 2, offer a new sensory experience to the audience. Oum’s Elephant without a Trunk (2023) is a giant sculpture made of wool, iron pipes, and pieces of sheet metal that was created after blind students sensed an elephant in a workshop. Christine Sun Kim’s Every Life Signs (2022), which explores the way language works and is translated, projects sign language gestures from different countries onto the wall and floor, inspired by the different sign languages and notations used by hearing-impaired persons. Soun-Gui Kim’s Gwangju. Poems (2023) juxtaposes a film of female high school students who recite poems by woman poets in the Joseon Dynasty period who were not acknowledged at the time with a film of a typhoon. Each of the three works invites viewers to rely on their senses of touch, sight, and sound to approach and experience them. If you close your eyes or cover your ears for a moment and walk through these works, you may lose your sense of location, bump into someone, or become very sensitive to the slightest sound. The act of empathising with those who have been discriminated against and marginalised is compelling in the immediacy of the biennale.

Oum Jeongsoon, Elephant without trunk, Iron sheet, wool and fabric, 300×274×307cm, 2023, The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission / Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation / Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

melanie bonajo, TouchMETell, Single-channel video installation, 24 min, 27 sec, 2019 / Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation

Care and Healing, Coexistence and Solidarity

‘Transient Sovereignty’ depicts the process of confronting the scars of colonisation and war at an individual and collective level and the possibility of healing through artistic practice. Guadalupe Maravilla, who crossed the border alone as a refugee at the age of eight, draws on his shamanic beliefs to create Disease Throwers (2023) in an effort to heal his personal wounds and trauma he experienced as an immigrant. Tracing the marks left by the Pacific War across the Korean Peninsula and Southeast Asia, the collective IkkibawiKrrr exposes the present landscape as a vegetation-covered terrain across which evidence of historical trauma like runways, strongholds, memorials and cemeteries honoring the victims have long been left unattended. Addressing the ecological and environmental crisis, the section Planetary Times attempts to shift our human perspective to a planetary one. Under this theme, Robert Zhao Renhui, from Singapore, photographs the wildlife and plants that have adapted to an environment around the tributary of a river where a concrete drainage pipe has been left unattended for 30 years, shifting the human gaze to that of an animal. Evidence of the atrocious acts of humans on our planet is also found in Alan Michelson’s Midden (2021). The artist, who is a descendant of an indigenous American tribe in New York City, recalls the city’s past covered with oysters and shells before environmental degradation, and projects the landscape of a river basin that has been radically altered by industrialisation onto a pile of shells. The oyster shells provided by Tongyeong for this exhibition will be used in a local recycling programme after the Biennale. The process of unearthing the memories found in nature and communities, and practicing planetary healing by cultivating a new imaginative power, requires humanity and art to act together in the face of the climate crisis.

Robert Zhao Renhui, Trying to Remember a River, 4-channel video installation, mixed media, Dimensions variable, 2023, The14th Gwangju Biennale Commission

Alan Michelson, Midden, Single channel video installation, mixed media, Dimensions variable, 2021

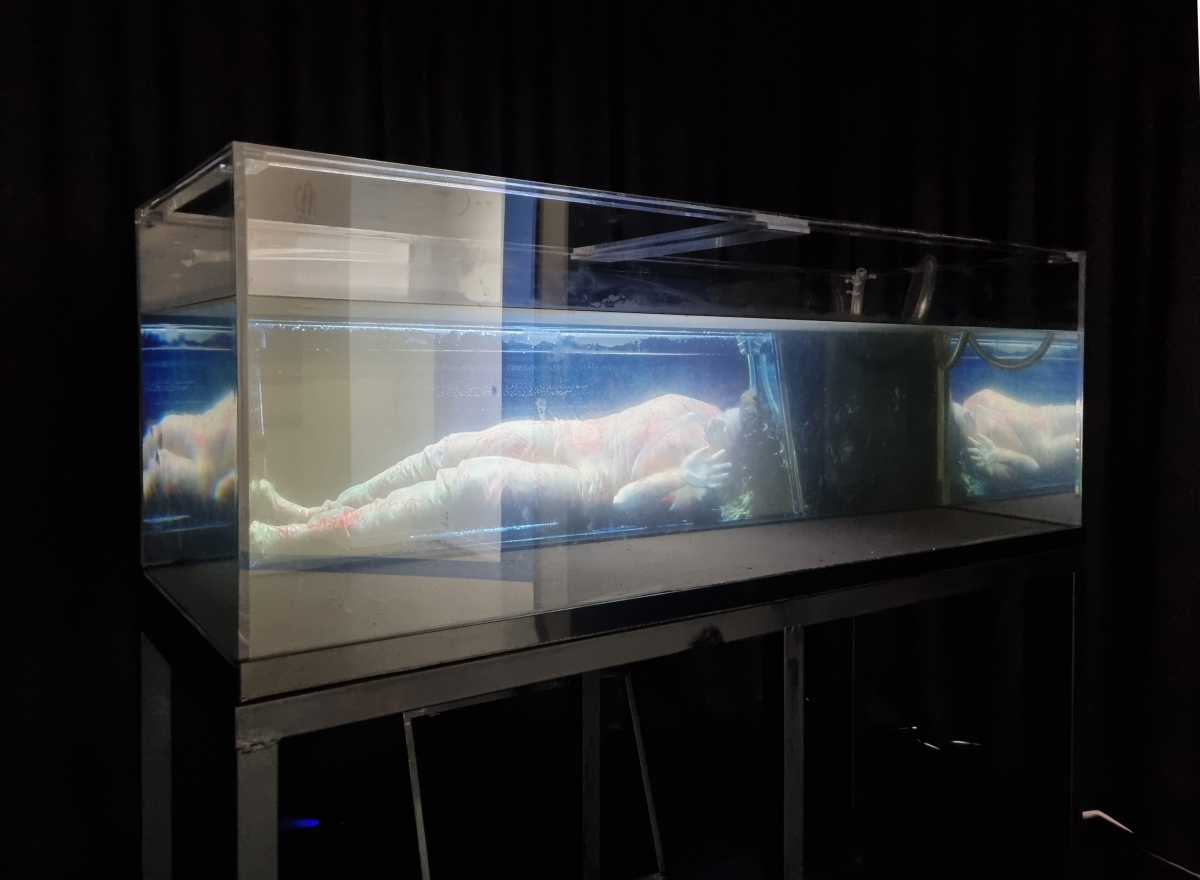

The Expanded Pavilion Project

The Pavilion Project, first launched in 2018 and expanded to nine countries this year, also continues to address times of planetary crisis. The Netherlands Pavilion, ‘Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: Extinction Wars’ at the Gwangju Museum of Art takes a more radical approach to addressing the climate crisis, presenting a trial-style performance. The exhibition enacts the Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act and puts animals that have gone extinct in the last 500 years on trial as victims. It also holds hearings against global corporations accused of environmental degradation and climate crimes, bringing them to account for a crime equally from a human and non-human perspective. In the Italian Pavilion’s ‘What does water dream, when it sleeps?’ at the Dong-gok Museum of Art, Agnes Questionmark presents an underwater performance about water, the source of life. Based on German biologist Max Westenhöfer’s (1871 – 1957) ‘Homo Aquaticus’, which predicted that technologically advanced humans would one day develop devices that would allow us to survive underwater in order to return to our evolutionary beginnings, the work depicts the artist entering a water-filled tank with only minimal vital equipment to return to a fetal state. The Canadian Pavilion at The LeeKangHa Art Museum, ‘Myth Becoming Real’ showcases paintings created by Inuits, Canada’s indigenous people, based on their own traditions and mythology. Familiarly anthropomorphised animals, reminiscent of fairy tale illustrations, capture the attitudes and way of life of the indigenous people who treat nature as a human being. A section on national efforts to protect their culture and habitat raises the awareness of indigenous peoples. The theme of exploring connections to the world through tradition and nature are expanded in various ways in the pavilions of other countries, such as the Chinese Pavilion which featured bamboo as a symbol of a unique spirit and traditional culture, and the Israeli Pavilion which looked at humans as objects and explored how humans relate to other objects and the world.

Installation view of ‘Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: Extinction Wars’ in the Netherlands Pavilion

Underwater perfomance Drowned In Living Waters (2023) of Agnes Questionmark in Italian pavilion ‘What does water dream, when it sleeps?’

Exterior installation view of Swiss Pavilion ‘Spaceless’

Expectations for the Biennale

In an interview on the opening day, Sook-Kyung Lee said she wanted to emphasise that just as ‘contemporary art reflects the present moment it connects with the history and traditions that brought us to this moment,’ alongside the artistic works of various cultures that have experienced discrimination, oppression, and inequality that also resonate with the history of Gwangju. Her determination to showcase a further evolved and expanded Gwangju spirit in conversation with its international community appears to have been successful. This is because most of the overseas participating artists are non-mainstream artists from the developing world whose work has rarely been seen in Korea, and more than half of the works were commissions, demonstrating a direct connection to the Gwangju spirit. In the absence of the so-called ‘big names’, their works received attention, occupying equal space and time in the exhibition. In contemporary art, where topics such as resistance, discrimination, inequality, colonialism, tradition, solidarity, and the climate crisis are no longer new, careful planning to provide a new exhibition experience becomes a means to increasing the sensitivity of the experience for visitors. The artistic director’s strategy of bringing the ‘image of water’ to the forefront may be related to this. It seems to have been an appropriate solution to create a more contemplative space by reducing the density of the exhibition, which encompasses a variety of media from traditional paintings to videos, installations, and participatory exhibitions. They are to be commended for attending to the theme so carefully throughout the exhibition, without the need for one strong representative work.

Nevertheless, there are some regrettable elements in this biennale. On 10 May, the Gwangju Biennale Foundation announced in an official press release that it was officially abolishing the Park Seo-Bo Art Prize, which had been controversial since its inauguration. This was in response to a fierce backlash from the local art community, which argued that an art prize named after a mainstream artist with no connection to the democratic movement undermined the Gwangju spirit. While there are still a lot of tasks to reach a consensus on the art prize, it left indelible impression that the whole process has been consumed by yet another political spectacle that attracted more attention than the exhibition. It may be time to check whether the ‘differentiation, scale, rationale’ and ‘Gwangju spirit’ frames, which are often used as labels when discussing the success or legitimacy of the biennale, are threatening diversity and experimentation.

There was also a glimmer of hope. Prior to the exhibition, the Gwangju Biennale Foundation organized a ‘GB Talk’ programme from September to November last year. At the first event, which focused on the climate crisis and the Anthropocene under the theme, The Necessity of Community to Solve Global Crises, participants agreed that the narrative of art should not be a ‘dichotomy of disaster or salvation’, but rather an attempt to find a third way (i.e., possibility of hope between the two). At the second event, which featured a diachronic and synchronic examination of Ye-Hyang that underlies the Gwangju spirit and a discussion of the practices of young artists in Gwangju, the ‘post-May 18 generation’ came to the fore. It was argued that at a time when the next generation, who did not experience May 18 Uprising, have become the subject of commemoration, the Gwangju Biennale needs to provide ‘a space where commemoration and interpretation can be safely separated, or a space and discourse where both can safely coexist,’ in order to ensure that May 18 Uprising is not sidelined as a historical event and that anyone can question and reinterpret it, without feeling indebted to it. Now, it is time to assess the clues laid in the discussions between practitioners, including artists, curators, researchers, and administrators, and consider how they will be transformed as strategies for the biennial’s ongoing evolution. The longest-running biennial in history (94 days) is still on show through the 9th of July, and the opportunity for criticism and reflection is still wide open.

Buhlebezwe Siwani, An Offering, Mixed media, Dimensions variable, 2023,The 14th Gwangju Biennale Commission

You can see more information on the SPACE No. 667 (June 2023).