SPACE July 2023 (No. 668)

While drawings provide evidence of architectural thinking and process, and publications disseminate architectural theory and criticism, photographs offer another means of investigating our built environment and understanding architecture. Based on the photography collection accumulated by Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) since 1974, ‘The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project’ is an institutional research project that examines the role played by photographs as works of art and documentation in the study and understanding of architecture. The project, conceived by CCA director Giovanna Borasi has been planned as a trilogy of exhibitions (2023–2026–2029). The trilogy is curated by different guest curators and attempts to interpret the collection from a new perspective. Bas Princen and Stefano Graziani, invited as the first guest curators, are photographers who have frequently collaborated with the CCA over the past decade. Throughout this interview, we’ll take a look at the project they’ve co-planned and now open to the world.

Exhibition view of ‘The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project’

Interview Bas Princen, Stefano Graziani photographer x Kim Jia

Kim Jia (Kim): ‘The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project’ is based on a collection of approximately 65000 photographs collected by CCA from 1974 to the present. From which perspective do you intend to shed light on the collection through this project?

Stefano Graziani (Graziani): We began thinking about an exhibition on photography following the ‘Multidisciplinary Research Programme for Architecture and/or Photography’ organised by the CCA in 2015. Our participation in this research collaboration between scholars and practitioners led us to explore the CCA’s photography collection more closely. It’s a large collection primarily focused on architecture, but we quickly discovered that many of the works did not strictly relate to buildings. Instead, they illuminated broader connections between social, natural, and built environments. These discoveries have expanded our thinking about architectural photography. We tried to trace a line through the collection from a historical and modern perspective by focusing on the way photographers establish their gaze to record the world they saw through the camera lens and the methodological perspective of using photographic media. Through this process, we wanted to shed light on CCA’s collection and spark various discussions about the contemporary photographic medium.

Kim: CCA’s photography collection ranges from individual photographs to albums, portfolios, videos, and large-scale digital photographs. Also, as it is composed of works by key photographers from each era, portfolios of famous architects, and CCA’s specially-commissioned series, the collection is extremely diverse in terms of its scale and themes. What makes CCA’s photography collection unique compared to other collections?

Bas Princen (Princen): CCA’s photography collection is, inevitably, related to architecture according to the direction of the institution. CCA’s founder, Phyllis Lambert, saw drawings, models, texts, and photography as important tools for studying the built environment. The collection is very strong in works from the early decades of the medium, including a unique collection of daguerreotypes, and key holdings by leading photographers active in United Kingdom, France, Greece, Italy, Middle East, and Asia during the 19th century. Several outstanding groups of works include large-scale commissioned documentation projects on urban redevelopment, civil engineering projects, development of railways, and construction sites, as well as mass-produced topographical albums and views. Of the photographs of projects, models, and built works by various modern international architects and agencies, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, Albert Kahn, and Ando Tadao are the most fully represented. The collection of contemporary photographs pays particular attention to photographic creation that adopts a discerning attitude towards architecture. Significant corpora have been assembled on the work of Geoffrey James, Robert Burley, and Guido Guidi, showing their long-term engagement with the built environment.

The research table in the exhibition was designed by Christopher Dyvik and Max Kahlen

Kim: What criteria did you use to select the artists and works for this project?

Princen: There are three simple criteria. First, one third of the authors are from the collection, setting the stage for the way we look, another third are artists and projects that we felt could have easily been part of the collection, but are not, for different reasons, but they complement and enrich the way we can see the collection, and the final third are artists we feel should be part of the collection in the future, since they push the idea of ‘straight forward photography’ to an extreme.

Graziani: We began with the authors we thought we knew better and are in the CCA’s collection. We studied photos from the nineteenth century to the present, and ultimately decided to begin our research with projects from the 1960s and 1970s. This was a period when photography became more autonomous and accessible as an artistic medium. We understand this as a period when photographers became liberated to develop their own rules for the medium and to declare what they saw as intrinsically valuable. Photography was no longer bound to commenting on social contexts or events; it could instead highlight a more personal or artistic way of looking at the world. Therefore, it was judged that this period would be suited to examining how they make visual claims of the changing architectural environment. The biggest concern when selecting each artist’s project was to show how the photographer’s subjective view of the world melted away in the process of reproducing the world as it is.

Photo books and magazines displayed on a table

Kim: Following the methodology of the CCA’s Collection, the exhibition presents materials as comprehensively as possible, encouraging the audience to appreciate these works and ask questions of them. Please explain your exhibition methodology in detail.

Princen: Our hypothesis that photography is itself a project has involved an exploration of the working approaches, processes, and methodologies of photographers across various stages from conception to production, and a consideration of how their projects are presented and reproduced. In using photography as artists, we have understood from the start that, the conventional ‘work on the wall’ is not the only authentic experience of a photographic projects. Books are equally important, or portfolios with proof prints. We feel it was important to show that these forms of representation have an equal importance.

Graziani: We did not choose a specific theme, and considered the seven galleries at the CCA as one continuous room. The exhibition is organised by project, mainly exhibited on ‘research table’. And a few works are on the walls. The non-linear design allows new encounters in the show and every work, every table has a new specific neighbour for the time of the exhibition. If we take the example of the books we included in the show, they represent different approaches to publishing, books made with publishers, self-published zines printed in few copies and dummies at different stages of development. In the case of Guido Guidi, Marianne Mueller, Lara Almarcegui and Gert Jan Kocken, specific editions have been made for this show.

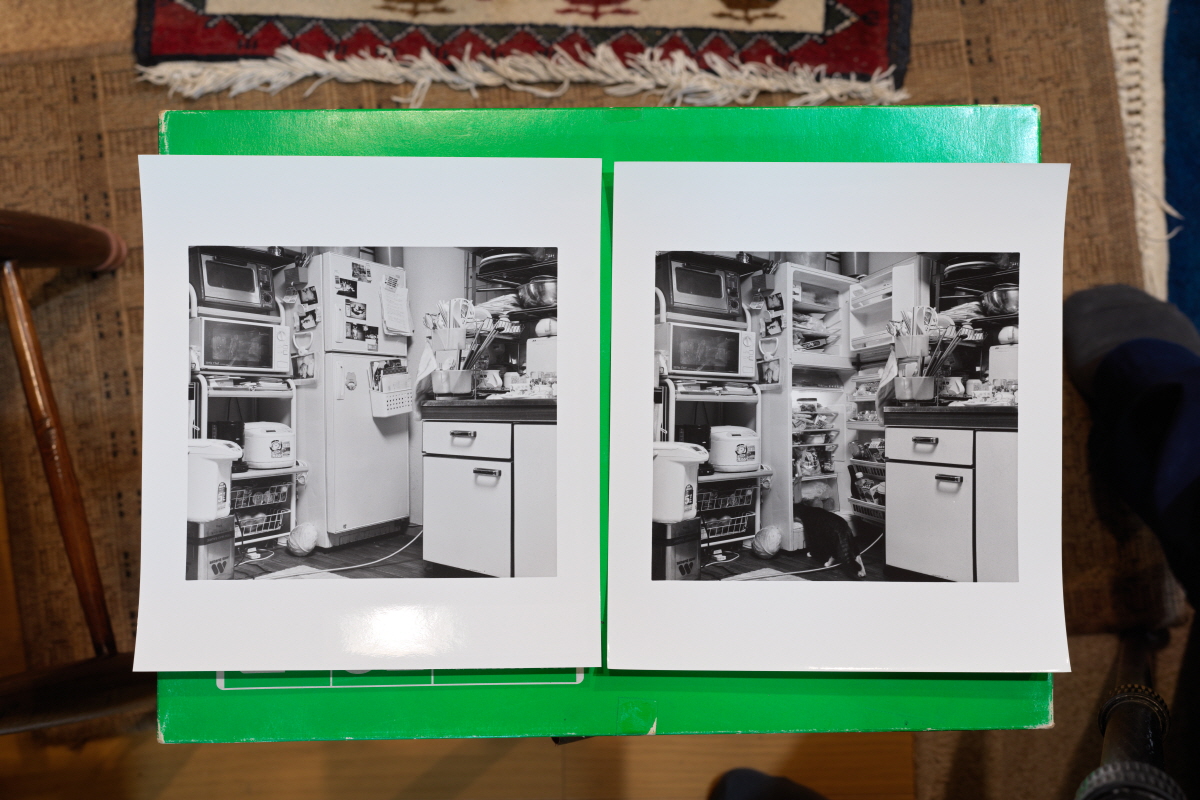

Ushioda Tokuko’s studio

Photos from Ushioda Tokuko’s studio

Kim: By interviewing the featured artists at their own studios, you captured their working approaches, research methods, and ways of thinking on video and in publication. What was your reason for choosing the oral history as your study approach?

Princen: We’re familiar with discussing architecture in terms of projects, but this isn’t necessarily the case when we think about how we understand or talk about photography today, which is more often framed in terms of the analysis of single, final works. Through this project, we wanted to consider the intentions and ideas of the author, which do not always align with how collections and scholars present their work. Through these visits, we began to trace the authors’ unique research methodologies more clearly: their distinctive ways of working, researching, and thinking about their projects. Surprisingly, we learned that for many authors, some projects we considered complete are ongoing projects that unfold parallel to the life of the author, changing and growing depending on time and experience. These oral histories can be important research materials, and possible way to reach a wider audience, when published online.

Kim: Photographers and artists could be involved in pushing the boundaries of architecture through their visual perspectives on how cities and landscapes should evolve. Could you tell us what kind of conversations you had with the photographers you met during the research process?

Princen: The artists we researched and met share an interest in depicting their immediate surroundings or the globalised urban world in a way that seemed familiar to them. Many works are critical, but not in exposing some kind of radical or futuristic visions. They depict things we can all see for ourselves, but when we see them organised and photographed by these artists, we realise that we have never looked carefully at our parts of our own environment. The power of these projects are in the ability to show you as a viewer way’s of looking at your own environment , wherever you are, they give you tools to visually connect.

Graziani: More than a friendly way, perhaps it is possible to detect a domestic, urgent approach to a familiar landscape. It is interesting and important at the same time to realise how some photographers for a certain period of their life have a specific interest in studying and documenting the most proximal areas to where they live, the places they know better. Examples would be Hatakeyama Naoya’s work in her tsunami-destroyed hometown, Rikuzentakata, or the New Industrial Parks near Irvine, by Lewis Baltz. Speaking about proximity and the gaze, perhaps it is interesting to say that for most of the authors the gaze does not change in front of different things and different places, in some way, although documentary, we are able to recognise the gaze of the different authors.

View of Landscape section

Kim: While photography assumes the role of a documentary that depicts reality ‘as it is’, however, it is also subjective. What do you think should be considered when using photography as a tool for research?

Princen: We should always believe that the photographer was there, in front of reality, as a person who sees something that is worth depicting. Now this sounds very banal, if I say this, but we are so much surrounded by images and depictions that if feels as if they are made by a certain automation, but we feel it is important to not forget the fact that ‘the photographer’ was there.

Graziani: Probably, if we begin to consider photography as a research tool, we shift to a new condition that becomes embedded in all what we look at and how we look at. As curators we might be able to find a new context for some works and for some research; as photographers we should also be able to step out of any context. For example, if we look at the artists’ part of this project we can say they all are independent and working on their own fields of interests, their own research. This research might or might not overlap with that of others. In the show there are both commissioned projects and self-commissioned ones, we did not distinguish between them. Professional practice is part of the history of photography and the life of many photographers.

Kim: Photography has a long history with human cognition. Do you think that photography still exercises a similar level of power in this age of technological advances and diversification of media?

Princen: I guess it’s all about seeing, that about how to depict what we see; the medium is everywhere and holds still a lot of power, not only in the act of photographing (that we all do on a daily basis) but even the still image retains its power, such as in advertising. Still photography is moving more and more towards the moving image, so the still image is also liberated from a certain overuse, the non-narrative aspect of a still image (I mean, it does not provide you a storyline) is still fascinating—it’s a document, it holds a lot of information and the images one encounters on the way are never silent, they keep asking me questions.

Graziani: Probably new media and technologies in relation to photography represent a social phenomenon more than a photographic and artistic one. Some works included in the show are, or become, iconic in terms of what they are researching whether different aspects of the landscape (for what they document) or photography itself. I don’t see any reason why photography should change if new technologies are developing, but it is interesting this question and this argument often reappear, maybe already in Atlante (1973) by Luigi Ghirri or in variable piece #70, everyone alive (1971) by Douglas Huebler, works that are both in the show. Photographers are always evolving and therefore so is photography. ‘Rock’n’roll never dies’ as Lewis Baltz was saying, probably referring to photography.

Exhibition view of ‘The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project’

You can see more information on the SPACE No. 668 (July 2023).