SPACE March 2023 (No. 664)

View of the entrance to the exhibition on the first floor / Image courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art

The annual exhibition at SeMA, Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, entitled ‘2022 Title Match: IM Heung-soon vs. Omer Fast «Cut!»’ opened on the 17th of November, 2022 and will be on display until the 2nd of April, 2023. This ninth rendition of the annual show breaks form with precedent and its practice of a two-person exhibition format inviting new and old domestic artists under the name ‘title match’. Instead, this time it adds variation to its exhibition format by inviting a foreign artist. The exhibition presents a total of thirteen works (including new commission works, early works, and representing works) by IM Heung-soon and Omer Fast, both well-known visual artists and filmmakers. The works of the two artists, which record, edit, and reconstruct the memories of individuals, groups, and wider society through cinematic form build new worlds that cross the boundaries between real life and the virtual world, documentary and fiction, all within the specific time and space of an art museum. Let’s follow the development of these worlds and the messages from beyond conveyed by these two distinctive artists, in an effort to unpick the differences and variations of their works.

Omer Fast, Garage Sale, 2022, 3-channel video installation, colour, sound, 29min 30sec ⓒOmer Fast

Title Match, Overlaps and Expansion

Born in Seoul, IM Heung-soon won the Silver Lion Award at the 2015 Venice Biennale with his documentary film, Factory Complex (2014), which contends with the instability faced by Asian female workers. In addition, he was awarded the Korean Fantastic Audience Award at the 21st Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival on Ryeohaeng (2019), the story of ten women refugees in North Korea. On the other hand, Omer Fast, born in Jerusalem and active in Germany, won the Bucksbaum Award in 2008 Whitney Biennial with his film The Casting (2007), a film which weaves a new narrative by segmenting and recombining text-image units. Furthermore, in 2019, he was awarded the National Gallery Prize for Young Artist Berlin-based artists under the age of forty in Germany. This exhibition combines the works of the two artists who are at the peak of their activities under the form of a ‘title match’. In general, a title match presupposes a confrontational win-lose structure. However, this exhibition seeks overlap and expansion beyond the structure of competition. Regarding this format, Song Kahyun (curator, Seoul Museum of Art) explains that IM Heung-soon and Omer Fast present diverse subjects with different languages and grammar. ‘What they compose on their screens is often so disparate and does not allow any competition or comparison. However, the specific subjects they choose often share similarities in that they reveal the structural forces that make up the world and existence, despite their specificity and locality. … they reflect on what an individual can do “nevertheless” in the face of a force majeure that occurs in various forms, such as war and terrorism, history and the state, and transcendent existence.’

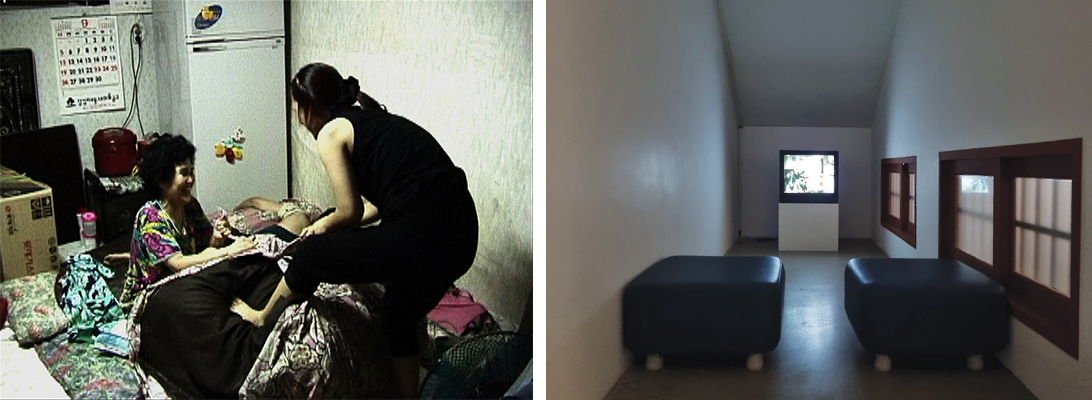

(left) IM Heung-soon, Basement My Love, 2000, Single channel 6mm, video, color, sound, 20min 9sec ⓒIM Heung-soon (right) Installation view ⓒBang Yukyung

Connecting Individuals with the World

It is Omer Fast’s new commissioned work Garage Sale (2022), which announces the beginning of the exhibition. Along with the clicking sound of the camera shutter, still-life images ‘zoom in’ and ‘zoom out’ repetitively, creating a frame story structure which weaves various stories together by tracking an ‘image within an image’. In the 3-channel video, three different stories are told against the backdrop of a garage sale where neglected, inherited items are sold. The story of an African-American woman purchasing ‘lawn ornaments’▼1, a symbol of racism from a white couple, the family history and the socio-political context involved in an unwanted but inherited legacy, as well as the overlaid voice of the narrator, leads the entire story. The narrative branches out through the different and competing contexts of violence, social issues, political action, and historical events. At the end, the artist confesses that ‘all of this is fictional’, through the speaker’s narration. However, the explorative journey crossing lines drawn between the past and present shifts the audience’s point of view to another dimension, regardless of its authenticity. It is the recognition of objects and memories which we may want to forget but cannot, and are perhaps believed to be forgotten but then suddenly pop-up, like inherited objects that were stored in the garage. The way the same scene is filmed and shown from different angles through the three channels represents the fragmented nature of memory. If Omer Fast reconstructs ‘the way in which an individual’s history relates to the world’ by reconstructing it in the form of a fictional story, IM Heung-soon’s Basement My Love (2000), located throughout Garage Sale, reveals how an ‘individual’s history expands to the history of an era’ from a first person point of view. Installed at the bottom of the stairway leading to the second floor, the film is a home video recording of the artist’s family on the day they moved to a rental apartment from the basement where they resided for nine years. As the family members organise themselves and move their belongings without being conscious of the camera, the phrase ‘But please don’t fall in love as I did. It will only cause you a heartbreak’ appears and intersects with images of the children. The overlapping scenes of the family looking at their basement room and reminiscing, alongside scenery of the new apartment conveys the joy and sorrows of a family who lived as workers of a sewing factory in Dongdaemun. The artists’ gaze, capturing the intimate secrets of life, stands at the boundary between a documentary and fiction, as both an observer and involved personnel. The camerawork maintains a psychological distance even in the midst of most intimate conversations between family members and draws the audience into its field of operation as an observer. This expands the autobiographical record into a microhistory of the era. The exhibition method of installing the screen in a semi-basement-like space also enhances the sense of immersion in the film.

(top) Omer Fast, De Oylem iz a Goylem (The World is a Golem), 2019, Single channel video, colour, sound, 24min 39sec ⓒOmer Fast

(bottom) Omer Fast, August, 2016, Stereoscopic 3D film, colour, sound, 15min 30sec ⓒOmer Fast

Cut, The Narrative of the Video

The phrase ‘Cut’, the exclamation given at the end of the title of the exhibition, is used in several different ways. At filming sites, ‘Cut’, is a shout to signify the ‘OK’ sign by a film director. It also signifies a grammatical format (a scene that was shot consecutively at once) that is unique to the medium of video and serves as a metaphor for editing techniques. In this exhibition, it refers to the concept of ‘a series of cut images’, which penetrates the unique characteristics of the video. This is where the similarities and differences between the two artists lie. The single channel video Continuity (2012), exhibited on the first floor, highlights the structural integrity of Omer Fast’s works, which recreate cinematic realities and meanings through the repetition of scenes and sequences. The camera portrays a German couple welcoming their son returning home from war in Afghanistan. As they repetitively go out in a car to greet their son, different actors appear as their son in each scene. In the latter half of the film, the couple follow a camel into the woods and find a pit littered with the bodies of soldiers. It is at this moment that the audience question whether the sons who have appeared are real, or if all these scenes are just neurotic delusions due to the trauma experienced at the loss of their son. The exhibition’s curator explains that ‘By repeating the given situation in the narrative the couple created, the structure itself contains their endless mourning and grief.’ In an open structure with no definitive clues, the audience can project their own experiences and memories to imagine and read meaning between the lines in various ways. Omer Fast stated in an interview after the opening of the exhibition, ‘It is the attempts to find order in a chaotic world and to understand the events occurring in it in an organised way which is fictional.’ This is the same in August (2016), and De Oylem iz a Goylem (The World is a Golem, 2019), where the boundaries between the virtual world and reality are blurred, as an expression of anxiety and neuro psychological state. The narrative structure which is segmented and repeated without a close link can itself be said to be Omer Fast’s unique grammar that accurately describes the emotions and psychology of modern people living under the reins of obsession.

(bottom) Omer Fast, The Casting, 2007, 4-channel video, installation, color, sound, 14min 10sec ⓒOmer Fast

Cinematic Time and Space

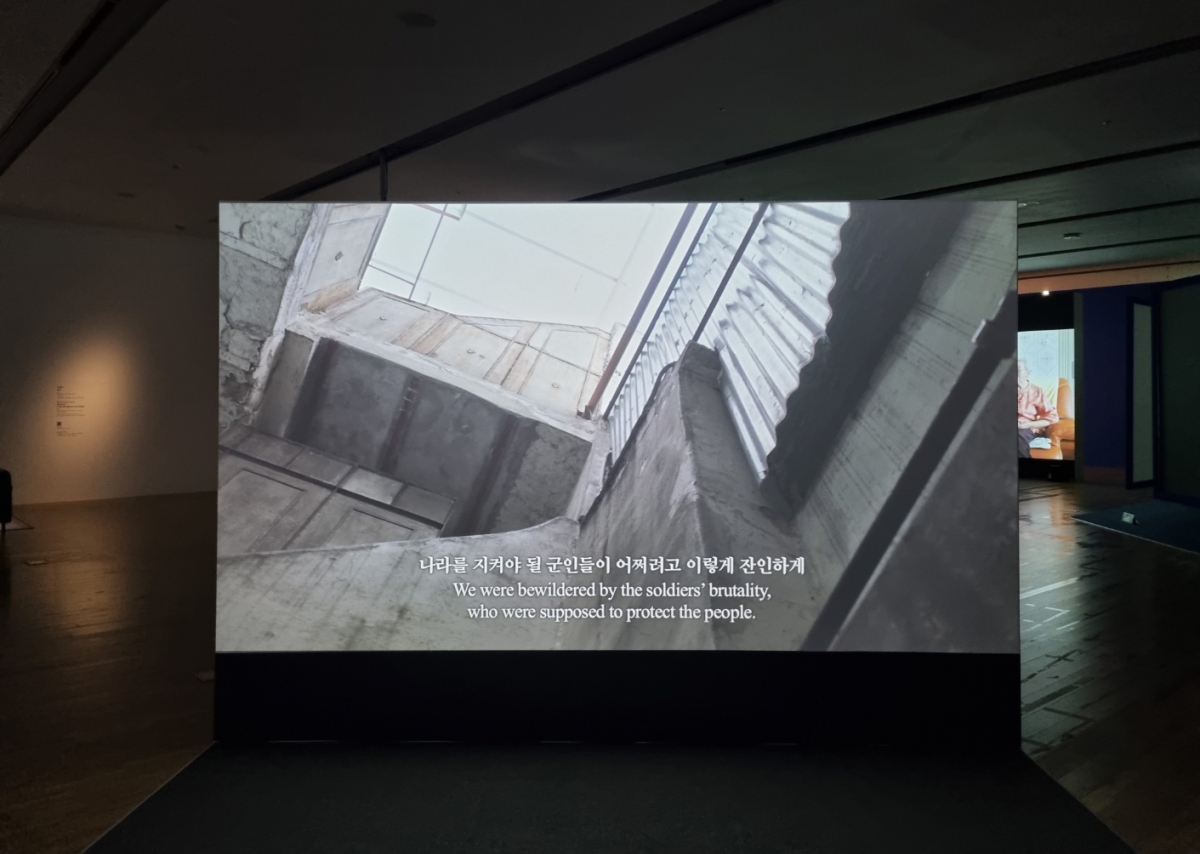

If Omer Fast reconstructs a story after completely disassembling a story according to its cinematic setting, IM Heung-soon differs in the fact that he reorganises a story so draw closer to the contexts of the original narrative based on interviews with the interlocutor. This difference in the storytelling approach is apparent also in the spatial character of the two artists’ exhibition. On the first floor, where Omer Fast’s works are exhibited, each individual work is separated by a temporary wall. On the contrary, the second floor where IM Heung-soon’s work is displayed, the exhibition hall forms an open space by hanging or fixing screens without any walls. The installation methods directly relate to the way in which the artists communicate with the audience. Omer Fast experiments with various screening methods: single channel, multi channel, multi screen, and hologram projection within individual spaces. This allows the audience to sense the change in narratives and form between works more dramatically as they move from room to room. On the other hand, IM Heung-soon’s works make the audience adjust their position by looking at both the whole and each part of the artwork through the repetitive actions of movement and pauses. Unlike movies and television, which focus only on the inner aspects of the screen, in an art museum the audience select and view the images on the screen more actively and subjectively. As IM Heung-soon explains, ‘the outside of the work also functions fluidly.’ IM Heung-soon’s Good Light, Good Air (2018) employs such methods, and invites the audience to experience the narrative of the film through a spatial dimension. In 1980, when the May 18 Democratic Uprising took place in Gwangju, South Korea, on the other side of the world in Buenos Aires, Argentina, an incident occurred in which civilians were sacrificed under the military dictatorship. IM deliberately installed two large screens facing each other at a distance and transmitted the videos of each event. A film of the clash in Gwangju on one side and Buenos Aires on the other. Amid interviews with victims and their families of events in the two cities, the work leads the audience to move between the two screens to face and unite historical tragedies beyond time and space. ‘Good light’ (Gwangju) and ‘Good air’ (Buenos Aires). The title, which unravels and lists the meaning behind the city name, both refers to and amplifies the message of these works.The 3-channel video The Waves (2022), a new commissioned work at the end of the exhibition hall on the second floor, portrays the story of people mourning and publicizing the hidden facts of a tragic incident caused by state violence. IM approaches the truths to the Vietnam War, Yeosun Uprising, and the Sewol Ferry Disaster not by interviewing those directly involved, but by interviewing the mediators (translator, historian, medium who held a ritual). Discovering the commonality of ‘state violence’ and ‘sea’ in the three incidents, he attempts to restore the lines of history that have been reduced and deleted by the spectacular images of news and provocative statistics. Confronting the reality that neither proper historical documentation of nor adequate reflection upon the tragic events took place, the three individuals in the story do not lose hope as they take their steps forward. The 3-channel videos of the interviews concerning the three incidents intersect simultaneously under the same soundscape and end with the image of waves rolling into the sea where the victims are buried. Composed of interviews and without any dramatic or brutal scenes, the film overlaps text and image, and thus asks the audience to knit various incidents and imagine a form of solidarity that transcends the boundaries of nation and period.

(top) IM Heung-soon, ‘Brothers Peak’, 2018, 2-channel FHD video, colour, B&W, 12-channel sound, 16min ⓒIM Heung-soon

(bottom) IM Heung-soon, Sung Si (Jeju Symptom and Sign), 2011, Single channel FHD video, color, sound, 24min 26sec ⓒIM Heung-soon

IM Heung-soon, ‘The Waves’, 2022,3-channel FHD video, colour, 5.1-channel sound, 48min 40sec ⓒIM Heung-soon / Installation view ⓒBang Yukyung

Confronting the World’s Reality

The preface to this exhibition introduces the works of IM Heung-soon, who recorded the history of individual sacrifices in war and disasters, as ‘a process of filling in the blanks of history by paying attention to the voices of the marginalised’. In addition, Omer Fast’s works, which cross the boundaries of documentary, fiction, and fantasy with their interest in how individual and collective memories are mediated and shifted, comments that, ‘It creates an intense cinematic space with its own narrative coupled with experimental media interpretation.’ The images of the world reconstructed through the eyes of the artists recreate a ‘cinematic reality’, and convey a powerful message that sits between reality and fiction. At the same time, the audience experiences various paths through which the museum is reorganised into a cinematic space. For example, in explaining the background to filming August, a 3D film on the life of the German photographer August Sander, Omer Fast noted, ‘[About the photos he took] In showing the moments before and after the photo was taken, I wanted to show not only the time sequence but the spatial sequence of being in front of and behind the camera.’ Just as his videos show the before and after of events, the audience will imagine and experience the ‘time and space outside the screen’ that more clearly reflects the darker and secretive aspects of the world, such as war, terrorism, discrimination, and hatred, through the exhibition. This may offer an answer to the question that the two artists pose: What can an individual can do ‘nevertheless’ in the face of force majeure?

1 The figurine that appears in the work, called the ‘lawn jockey’ in a horse jockey costume, was a common garden decoration in American homes until the mid-20th century. The figurine comes in various forms, but it mainly takes the shape of a figure holding a lantern or a hook to hang a horse’s leash. The problem is that most of these lawn jockeys portray black people in a racist manner.

(top) IM Heung-soon, Good Light, Good Air, 2018, 2-channel FHD video, colour, 4-channel sound, 42min ⓒIM Heung-soon / Installation view ⓒBang Yukyung

(bottom) View of the exhibition on the second floor / Image courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art