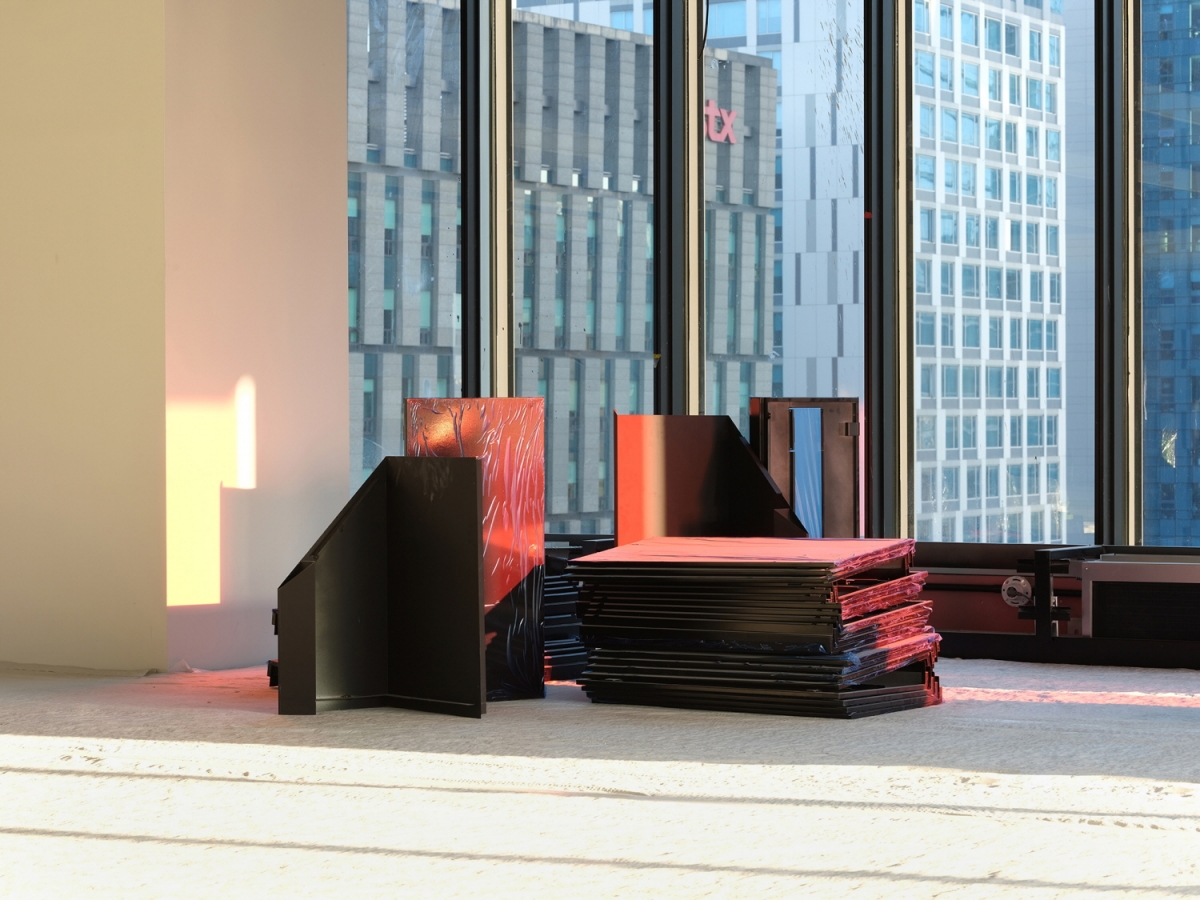

top image Construct 1102_7587, Pigment print, 150×200cm, 2017

SPACE April 2023 (No. 665)

Photographer Jihyun Jung, born in 1983, began his documentation of urban space as a consequence of his experience of loss as an ʻapartment kidʼ. He witnessed the moment at which the Jamsil apartment complex disappeared, a setting central to many memories from his childhood. After traveling to and surveying demolition sites in redevelopment areas, he expanded his area of research activity to new construction sites, and now hovers between the fields of architecture, materials, surfaces, and structures. Who is this figure, one who uses architectural terms such as excavation, tensile strength, and curtain wall, while also conveying an certain unfamiliarity with architecture?

Reconstruct 301_4545, Pigment print, 180x135cm, 2020

interview Jihyun Jung artist × Youn Yaelim

Youn Yaelim (Youn): Looking back to the early 2000s, when your interest in cities emerged, you began documenting the appearance of first-generation apartments exactly as they stood.

Jihyun Jung (Jung): While Seoul Metropolitan Government instigated the New Town project around 2005, those historically significant first-generation apartments were demolished indiscriminately. At the time, some artists and art collectives were moved to protest activities such as occupying the demolition sites and staging sit-ins. This was also an important moment for me. I thought about what I could do as a photographer, and I decided to record the oldest remaining apartments in accurate detail. I carried out this engagement with these spaces with the taking of funeral portraits in mind, offering no distortion from the reality I faced.

Youn: In Demolition Site (2013) and Reconstruction Site (2015), you expanded upon your role from an observer behind the lens to an interventionist playing with the apartments. You sneaked into an empty apartment with a red paint can and created an entirely red room.

Jung: If the goal was simply the visual production of a red wall, it would have been enough to take a photo and add colour in Photoshop after shooting overnight, but the creative process was more important to me than the result. I went through the process of persuading various parties, seeking agreements, building relationships, and understanding each other on-site. The series Reconstruction Site turned this process into works of art. While I communicated with the reconstruction association at the time to obtain permission to take photos, I was also able to gain a stronger sense of their relationship. Those who live as neighbours for many years without knowing one another finally come together only when their homes are under threat of demolition. I explored this striking realisation in Reconstruction Site and painted every wall red throughout the floor, instead of just the individual rooms. The red walls, which are segmented into individual spaces for each unit before the start of demolition, are gradually connected as a single line while the front walls were torn down. I wanted to express the disorientating realization that they have all shared and faced these same walls on the site of the destruction caused by reconstruction.

Youn: However, the pictures that follow the demolished apartment do not have clear emotive profiles, such as nostalgia, empathy, or anger. The art critic Jung Hyun noted, ‘Jihyun Jung’s photographs encourage viewers to stare into them rather than initiating conversations.’ What is the meaning behind this work?

Jung: This is the reason why there is not a single picture of an excavator among the works you mention. When I first presented the ʻ-siteʼ series, I was asked a lot of questions like, ʻSo, are you for or against redevelopment?ʼ However, in advance of the superior value of economic profit, the voiced pros and cons lose strength and became meaningless in debate. Instead of making such judgments, the ʻ-siteʼ series focuses on the process of documenting the urban phenomena of redevelopment and reconstruction. Therefore, I excluded the more intrusive or even violent elements such as excavators that are reminiscent of aggressive scenes or create a provocative atmosphere. More than a decade has passed since I finished the ʻ-siteʼ project. When I presented the series, many regarded the apartments in the photos as shameful losses to be reconstructed as soon as possible. However, it is rewarding that as the times change, the apartments have become a representative image of that era and culture, and more and more people are nostalgic for the old five-storey apartment. Apartment kids who were born and raised in the city regard them as their hometown landscape. It is interesting that they have prompted these associations and personal lore.

Demolition Site 01 Inside, Pigment print, 120×160cm, 2013

Reconstruction Site 9, Pigment print, 140×180cm, 2015

Youn: While you’ve recorded the scenes of destruction known as demolition, more recently you have been spending time on new construction sites. This is in line with Construction Site (2012), which recorded construction sites in new town. What served as a momentum to shift your interest from disappearing objects to the sites of creation?

Jung: In many cases, demolitions and new constructions occur simultaneously because of the nature of rapid development. Demolition takes place on one side, while new constructions go up right next door. Walls painted red eventually become red stones and they are used as recycled aggregate on new construction sites. I felt that the city was changing with demolition and construction in constant circulation. The Pangyo New Town just happened to be developed at that time, and it naturally became my next destination.

Youn: Starting with Amorepacific Headquarters in 2017, you also recorded the construction sites of ST International HQ and SONGEUN Art Space (2019 – 2021) and Samil Building (2020 – 2021). How did this differ from your previous experiences on demolition sites?

Jung: I was always pressed for time when I was carrying out my projects on apartment building sites. After using hundreds of thousands of KRW worth of paint, I was almost in tears when I found it crumbled into pieces the next day when visiting to take photographs. However, I couldnʼt say, ʻI am going to work on this section, so please break it down at a specific point in the day.ʼ (laugh) Commissioned projects on a construction site can provide a much more stable environment. Nevertheless, construction sites are rough and full of variables. In general, artists often find it difficult to cope with the parameters of a construction site. In my case, thanks to my long experience of the learning order of construction sites, I was able to work without interruption during a construction period of 1 to 3 years.

Construction Site 12, Pigment print, 125×155cm, 2012

Samil Building Remodeling Documentation: Curtain Wall, 2020

Youn: When an artist, and not typical construction site photographer, is commissioned to record the changes to a site, client is expected to do something different. What do you think that something different is?

Jung: When large-scale art museums are constructed in other countries, documentation is frequently left in the form of pure art in addition to on-site archives. Artists create original content while upholding the informative power of architecture. Classified as product photography, ordinary architectural photography emphasises the sense of space, great views, and splendid technology, but sometimes these aspects also intervene to make it difficult to understand the space properly. Since October last year, I recorded the construction site of the Seoul Museum of Photography, Koreaʼs first photo-oriented public art museum. Here, the characteristics of the land, which used to be a landfill site, were considered. I photographed the section of the stratum that was exposed during excavation work. Whatʼs different about my photography from traditional commercial photography is that I do not focus on a complete building, but on those small points that expose and chart the life of a building.

Youn: As a photographer, I think you may have a different perspective on the perception of space to architects.

Jung: I always try to communicate with architects. Communicating directly with architects and those in charge of construction, implementation, and supervision, I devise works in collaboration them to draw on the structure and construction methods behind a building. Participating at the test stage of tensile strength and wind pressure assessments before construction, when related data is also shared with me, I checked them all with the naked eye when on site, and learnt a lot from them. Based on this, I tried to figure out the architectʼs intention in this building and perceive the driving aims. This is the key theme behind and starting point to my work. Once standards are set like that, my works over the years have become connected on different floors, in different spaces, and at different points of view. I try to make a building appreciated in my pictures even after it is separated from a description about its future status, and to adopt value as a work in itself.

Construct 010_5619, Pigment print, 135×180cm, 2017

Reconstruct 101_5268, Pigment print, 135×180cm, 2020

(left) Structure Studies - Topology #01_8488, Pigment print, 210×160cm, 2019, (right) Reconstruct 301_3953, Pigment print, 180×135cm, 2020

Youn: Examples may include Construct (2017) series at Amorepacific Headquarters, Topology (2019 – ) series at the ST International HQ and SONGEUN Art Space, and the Reconstruct (2020 – 2021) series of the Samil Building site. I noticed you mentioned the notion of ‘recycling the site’ in these works. What aspects of the site did you draw upon?

Jung: While the development of construction sites in the past tended to take place every 10 or 20 years, the current rate of change has become much faster, and I think it will continue to accelerate in the future. I think the development of flexible architectural materials and modular building methods is behind this change. Sensing contemporary trends and using them in my work helps me to create many different stories in my artworks. The important point is that a theory can be organised and expanded not just from one picture taken at a specific building, but from a similar typology of contemporary architecture. For example, the Samil Building is historically significant in that it is the first curtain wall building in Korea designed by architect Kim Chung-up. Therefore, the focus was on documenting the restoration process of the curtain wall. The Reconstruct was based on the thin materials that make up the Samil Building. The process of covering the existing walls with new construction materials was captured while filming the materials by arranging them flat. I documented the process of covering the existing walls with new architectural materials by taking pictures of materials arranged in a flat plane. Old and new materials appear one after the other, and the rough walls are hidden in a new and smooth section of the building once construction is completed. Meanwhile, the photographs of the sedimentary layers taken at the Seoul Museum of Photography expressed overlapping timeliness by adding several layers of silkscreens. This is an attempt to transfer non-materials such as textures and reflect the shifts in time that digital photos cannot record as physical forms. I think such works are about expanding and understanding space in various ways. They consider the structures that exist behind walls so that we can excavate the process of building even after completion.

(left) Reconstruct 101_4911, Pigment print, 180×135cm, 2020, (right) Cut slope #6020, Silkscreen on pigment print, 90×70cm, 2022

Youn: You seem to regard buildings as constantly moving and changing beings, like humans.

Jung: To me, the instability I feel when taking photos of people is no different from that I feel when photographing buildings. The ever-changing construction and demolition sites are scenes that cannot be seen again if not documented as they will soon be covered or disappeared. Every day, I think of it as capturing the last breath of the buildings. Thatʼs why I focus more and make physical contact with them. When I paint the surface of architecture, move materials, and breathe in dust from them, I feel as if I am having an in-depth conversation with the building. Strangely, as I follow that conversation, I often end up facing the elements that the building has also long withstood.

Youn: It seems novel to use the word instability in reference to buildings that are usually described as huge immobile objects.

Jung: When I spend all my time on a rapidly changing construction site, I sense time differently. Sometimes, I feel a certain pressure to encounter a site that changes every day because the scenes that have passed wonʼt come back. In this case, I try to visit at a quiet time and have the building with me. In fact, what the artwork means in society and how itʼs exhibited is a different story, and the building and I are everything to me. As such, capturing architecture on camera is a fascinating task for me.

Demolition Site 05 Outside, Pigment print, 120×160cm, 2013

You can see more information on the SPACE No. 665 (April 2023).