SPACE December 2022 (No. 661)

SPACE No. 84 (Apr. 1974) ▶ e-magazine

In Korean art of the twentieth-century, imitation was at the root of all concerns. The idea that the history of Korean art is only one exhaustive repetition of Western art movements and not characterised by autonomous developments with their roots in earlier practice has often led to criticism and concern about the nature and future of Korean art itself, as well as self-deprecation and resignation. The colonial legacy that underpins Korean art, which began in earnest through the introduction of Western art discourses, institutions, and technology, was systemic, permanent, and could not be overcome voluntarily. Many felt one would be able to open up the art of this land without restrictions now that it had escaped from the strictures of the Japanese colonial period. However, it suffered a tremendous setback as it was rendered subordinate to and dependent upon Western art. During the Japanese colonial era, a sense of Korean tradition was obscured and modernity was polluted, so there was no precedent to follow up. So, instead, it tried to improve the nature of Korean art and begin again anew by learning from and pursuing Western precedents from a ‘zero-base’ knowledge base. As such, imitation was not something to be rejected or belittled by latecomers to contemporary art. The important thing was to adopt what was relevant for modern practice in this country rather than taking issue with imitation itself, as even if it was an imitations it was to take root, lay the foundations for Korean art, and bear fruit. In this way, the imitation had to be grounded or motivated by the conditions, reality, temperament, or any other characteristic defining the land: imitation with a necessary connection not arbitrarily chosen or imposed from above. The counterpart to imitation in Korean art was ‘inevitability’ rather than ‘creation’.

SPACE No. 84, p. 8.

The art critic Park Yongsookʼs ‘Why, It Is Ideological?’ published in SPACE No. 84 (Apr. 1974), again raises this chronic problem. Regarding the diverse trends that emerged after the war in Korean art, he asks, ‘What is necessary when we say that we adopt the style of an ideological art practice?’▼1 Here, ʻideological artʼ is not conceptual art as was popular in Europe and America at the time, but contemporary art in a broader sense that originated with European expressionism, dadaism, and surrealism in the early twentieth century. They are philosophical and idealistic because they are not simply inventing a new visual language but a kind of ‘mental adventure’ troubled by the crisis of western civilisation. The crisis is nothing other than the development of science and technology, the advancement of capitalism, the deepening of rationalism, and the civilisation created by human beings suffocating human beings. Park explains this as ‘the image created by humans as their lives deviated from their original function, and instead interfered with and threatened the essential quality of life of humans’.▼2 Therefore, as a challenge to this, the task of art in the twentieth-century is to ‘return the image (the delusion) to its original form’, in other words, ‘to turn the delusion into reality’. The perspective of looking at contemporary art as an attempt to suspend and overcome perception and cognition inherent to rationalisation, commercialisation, and instrumentation of the era, is an example of what it introduced to the Korean art scene in the late 1960s and has since become a preoccupation in art circles.▼3 Contemporary art should structure the moment of ‘encounter’ that suspends humanistic meanings, usages, and premises already familiar in the world. Parkʼs theory of ideological art touches on a phenomenological approach that erases the existing ideas imposed on the world.

SPACE No. 84, pp. 9 ‒ 10,

SPACE No. 84, pp. 17 ‒ 18.

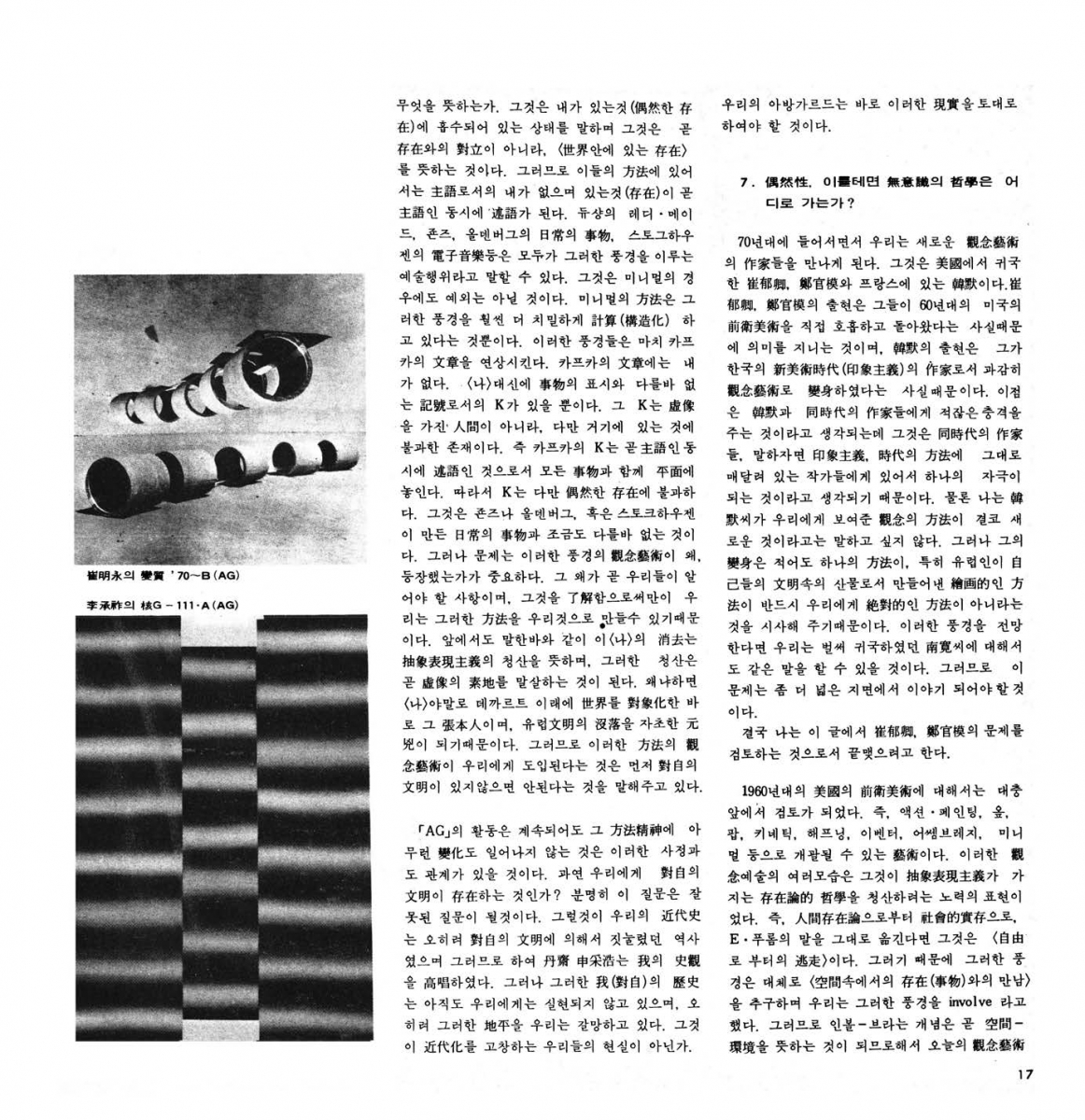

As such, if Koreaʼs post-war ‘avant-garde’ informed by movements such as informel, pop art, op art, minimal art, kinetic, happening, and recent object art and monochrome painting ask art to overcome the spiritual crisis of western civilisation, one naturally asks the following questions: Is the mental health crisis a matter of urgency to the extent that so many works of ‘ideological art’ have resulted?; Are we suffering from a reckoning with the illusory to the point that we are shunned and need ‘realisation’?; How seriously is the language instrumentalised and humanistic why, in Korea, does informel or happening refuse to be semantic and present an instant presentation? Parkʼs answer is firm. He says that such illusions, civilisations, and reifications are not yet our ‘reality […] because we have not yet realised the horror of illusions like the Europeans’). In a sense, rather than suffering the slings and arrows of civilization, is it not that we havenʼt yet fully experienced civilisation? (‘Isnʼt it our reality that promotes modernisation?’)▼4 Accordingly, Park points out that ‘our ideological art is not strong in its influence because it lacks the historical necessity for ideological art to appear’. At the same time, it reminds us that ‘the problem is not the introduction of many methods, but the question of why such methods were created and why such methods have to come to us’.

The questions and arguments raised by Park are not new in that they were raised during the Japanese colonial period and have been repeated by several commentators since the 1950s. In the late 1960s, pop art, op art, kinetic art, environmental art, happenings, light art, and object art poured into the Korean art scene. However, Western industrialisation, consumerism, and technological development through those models also emerged in Korea, which had just entered a stage of industrialisation and urbanisation. Therefore, it is questionable whether it led to a reflection on artistic experimentation and the absence of ‘inevitability’ in Korean art in general. Art critic Lee Yil lamented that ‘we have never truly experienced our own reality in the act of art’ in that they were only seeking to transplant it. In addition, aesthetician Zoh Yohan noted, ‘while Korean artists are in the process of industrialisation, there is a tendency that they are experiencing the concerns of the European art world, where technology in everyday life has become commonplace’.▼5 Why doesn’t the art of this land find new clarity in desperate experience? Why does it only advance other people’s concerns? These rhetorical questions summarise how the (post-)colonial situation of Korean art is being once again extended by Park Yongsook through the case of Korean art in the 1970s.

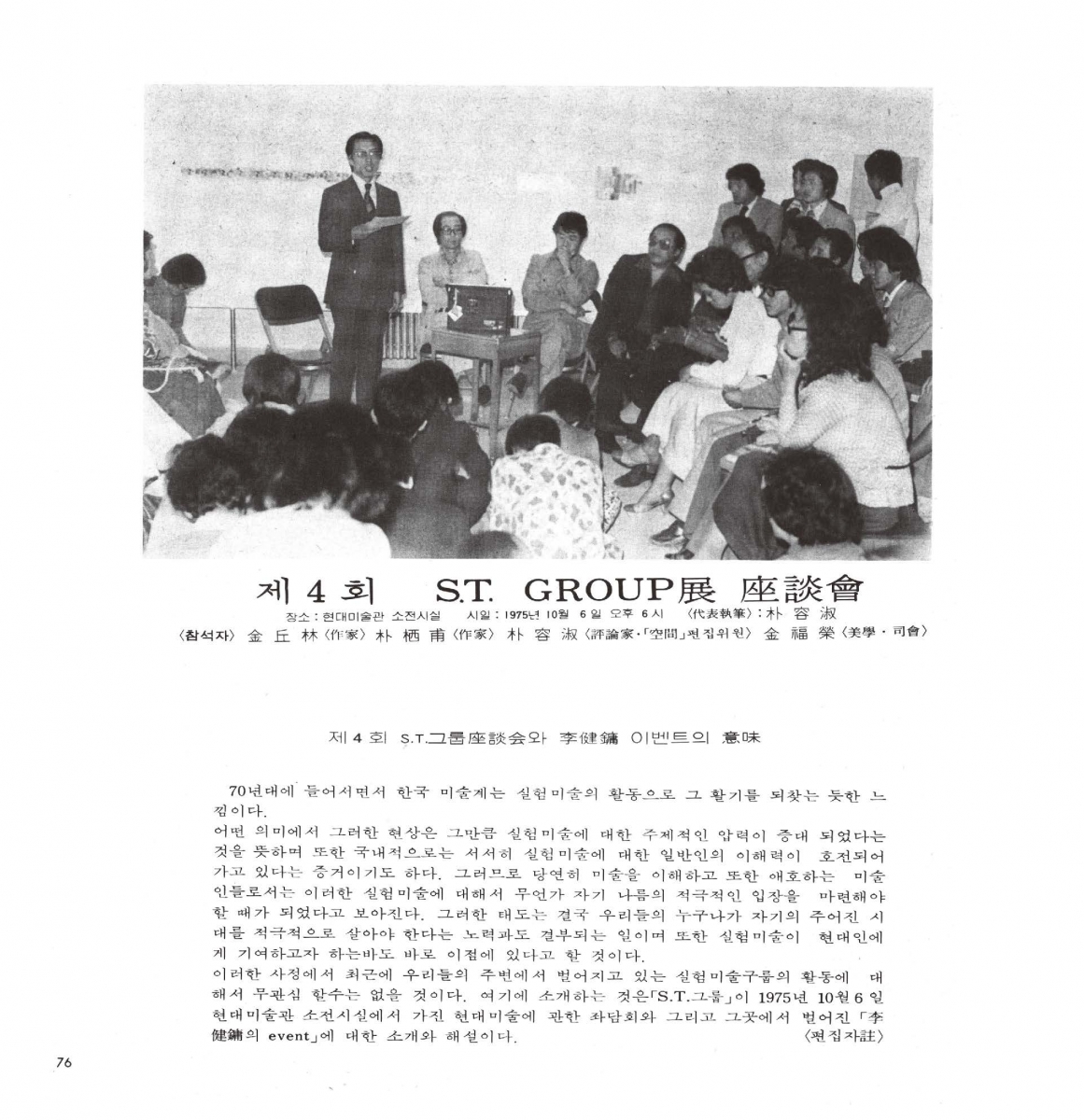

SPACE No. 101 (Oct./Nov. 1975), pp. 76 ‒ 77.

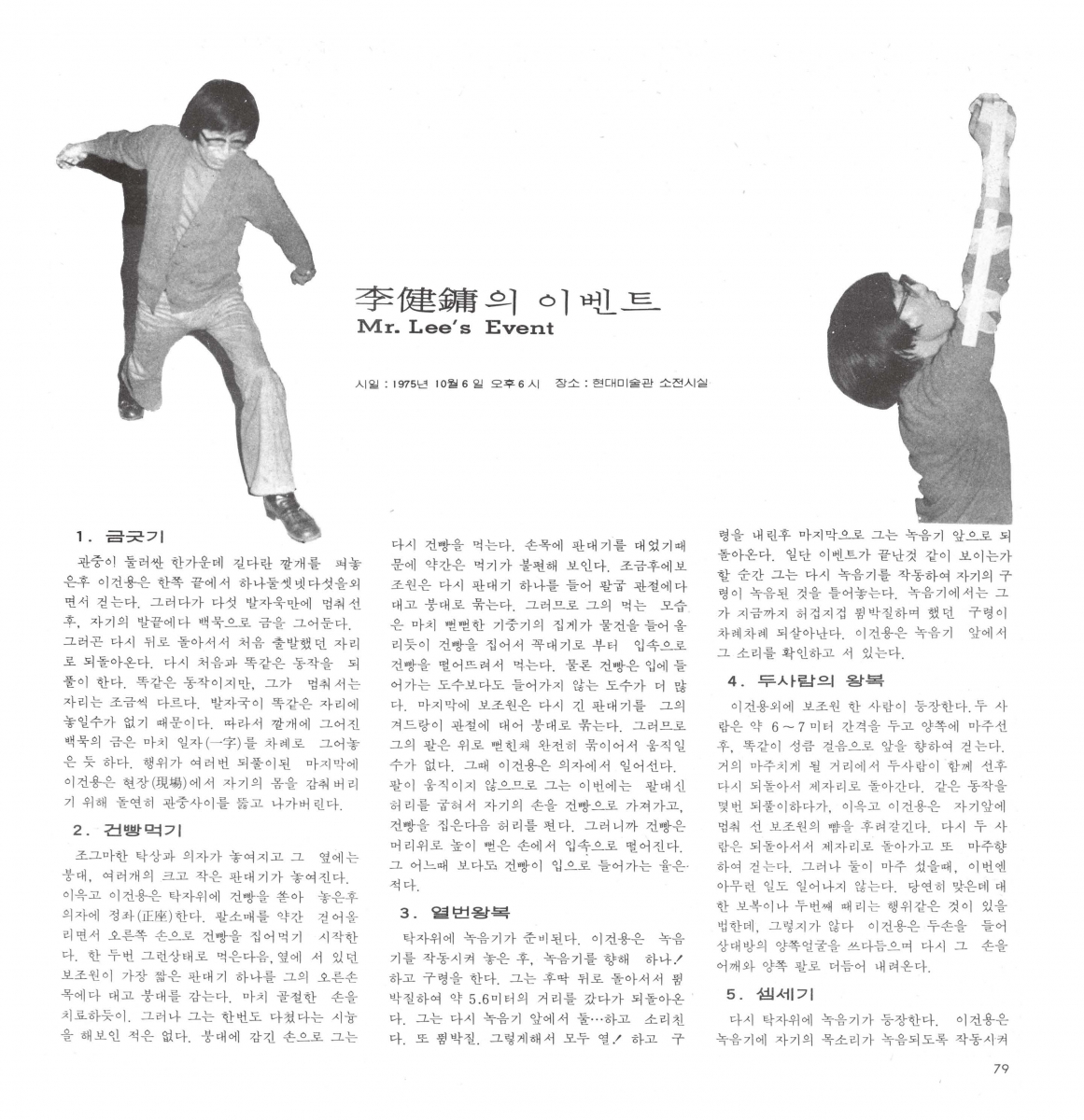

SPACE No. 101 (Oct./Nov. 1975), pp. 79 ‒ 80.

They also partly explain the historical meaning of his writings. Transitioning to the mid-1970s, vocabulary such as ‘Lao-tzu’, ‘Chuangtzu’, ‘Oriental’, ‘spirit’, ‘inoperativeness’, and ‘white’ were used in discussions of Korean art. They delivered a sense of ‘necessity’ in the white monochrome screen and that repeated brush strokes derived from the ground. As if it was the fruit of introspection and reflection on the Korean art that exploded in the late 1960s, it seemed that the art of this place was no longer concerned with resolving other people’s concerns but those of the tradition, temperament, aesthetic sense, or in terms of the experience of this place. However, Park tells the opposite story. Monochrome painting through repetitive drawing is a method found in Western ‘ideological art’ that removes intention from the screen and suspends signification, thus rejecting illusions. It suggests that the problems endemic to ‘imitation without necessity’ were not resolved in the 1970s, and therefore some assertions are deceptive and expectations misleading. There are several problems with his argument. How can Western avant-garde art of the twentieth century be understood under one project titled the ‘realisation of illusion’? (Individual works and artistic trends are here only sacrificed to a sense of Hegelian totality.) A more severe criticism is whether phenomenological art was unrelated to the experience of this land in the 1970s or even before that. (In this sense, he seems to have internalised more than anyone else the idea that there is a profound gulf between our situation and that of the West.) Interestingly, it can be said that Park’s contribution was not to extend the longstanding critical powers of Korean art but rather to make people understand that there was a phenomenological impulse to bring back the world that was signified and objectified in Korean art in the 1970s.

SPACE No. 82, pp. 57, 62.

He later expands the framework to the ‘events’ of the S.T. Group, including those explored by Lee Kunyong, across various pages of SPACE. Their repetitive and tautological performances of walking, sitting, standing, and drinking are explained as the attempt to remove purpose and intention from action.▼6 Therefore, it identifies the primary trend of art in the 1970s as a kind of reification programme, whether painting or performance. In this respect, it can be said that Park understood the art more closely and deeply than anyone else to be able to diagnose and criticise the chronic problem of ‘imitation without necessity’ repeated in art of the 1970s. This paradox is not unrelated to his radical yet flexible stance.

SPACE No. 101 (Oct./Nov. 1975), pp. 76 ‒ 77, 79 ‒ 80.

It was in 1973 when novelist and art critic Park Yongsook, who had suffered from the 1971 National Council of Defending Democracy incident, took over as editor-in-chief of SPACE. Looking back on that period, he says, ‘At that time, my interest was nationalism.’▼7 In fact, he tried to pave the way for new experimentation between the growing demand of popular discourse and an increasingly threatening political environment by planning an issue on liquidating the remnants of Japanese colonial rule or devoting discussions to ‘national realism’.▼8 Therefore, his critique of the colonial legacy in Korean art is not surprising. However, at the same time, the editor-in-chief of SPACE was naturally exposed to various modernist and experimental trends of the period, meaning he understood them through continuous experience. (‘Many avant-garde plays, avantgarde art, especially happenings, and events have become one of the leading events of the SPACE Institute […] My eyes toward art have gradually turned to broader and more diverse things’)▼9 Therefore, he could take a more flexible and open attitude towards the ‘avantgarde’, which was only imitative thinking for the practitioners of a rising national and popular art discourse at the time. Park’s ambivalent attitude was none other than that also adopted by SPACE at the time, and at the same time, it was also its strength.

The ‘RE-VISIT SPACE’ series that began in 2021 will now enjoy a pause. We want to thank the writers for their hard work and the readers of the past two years.

1 Park Yongsook, ‘Why It Is Ideological?’, SPACE No. 84 (Apr. 1974), p. 10.

2. Ibid, p. 9.

3. On ‘Lee Ufan Effect’, Shin Chunghoon, ‘Korean Art and the Lee Ufan ‘Effect’ of the 1970s’, SPACE No. 657 (Aug. 2022), pp. 124 ‒ 131.

4. Park Yongsook, Op. cit., p. 17.

5. Lee Yil, ‘The Ethics of Transformation - Where Today's Art Stands’, AG 3 (1970), p. 34; Zoh Yohan, ‘On the Experimental Nature of Contemporary Art’, Hongik Art 2, (1973), p. 60.

6. Park Yongsook, ‘Experimental Arts, How to Live Actively’, SPACE No. 101 (Oct./Nov. 1975), pp. 76 ‒ 78; Park Yongsook, ‘Mr. Leeʼs Event’, Op. cit., pp. 79 ‒ 80.

7. Park Yongsook, ‘When I was the Chief Editor of the Magazine SPACE’, SPACE No. 300 (Sep. 1992), p. 51.

8. Park Yongsook, ‘Is the National Realism Possible?’, SPACE No. 82 (Feb. 1974), pp. 57 ‒ 68.

9. Park Yongsook, ‘When I was the Chief Editor of the Magazine SPACE’, p. 51.