SPACE December 2022 (No. 661)

Sanghun Lee’s Seoul Urbanism, published this November, analyses the characteristics that inform Seoul’s urban form, focusing on nine keywords: street-parcel-block, building, area, superblock, patchwork, facility layout, street scenery, public space, and nature. By scrutinising Seoul’s urban structure and its principles, which is formed through a mixture of physical conditions, city planning, administrative and legal regulations, this is ultimately the product of a critical effort to discover Seoul’s identity. In this interview with the author, we talked about how the author focuses on urbanism, the process behind writing, and the implications of this book for the Korean architecture community.

interview Sanghun Lee professor, Konkuk University × Bang Yukyung

ⓒChoi Damee

Bang Yukyung (Bang): Following There is No Architecture in Korea (2013) and The Identity of Korean Architecture (2017), this is the third book on Korean cities and architecture you have had published. It’s a new book that took five years to complete. What prompted you to write a book on this subject?

Sanghun Lee (Lee): There is No Architecture in Korea, was an attempt to discuss the structural problems faced by the Korean architecture industry, based on the points that had come to be seen as unreasonable or unacceptable in Korean architectural education and practice. Accepting the present situation in the architectural world, which is largely westernised and has fallen second to the construction industry, I proposed the necessity of the ‘theoreticization of tradition’ and a ‘theory on urban form’ as two areas for the development of Korean architecture. My intention was to envisage a healthy future for Korean architecture only when these two areas are properly established. Although I criticise Korean architecture here, I felt

burdened to come up with alternatives as a theorist and a stakeholder presenting problems. If The Identity of Korean Architecture, published four years after, is the answer to my previous work, Seoul Urbanism can be said to be the answer to the challenges that follow. I feel like I finally finished the homework that I set myself ten years ago!

Bang: In this book, you offer an urban morphological analysis of Seoul. What is the difference of this approach compared to other academic frameworks dealing with cities?

Lee: I’ve been thinking about writing a book about Seoul for a long time. I was particularly interested in the process behind the formation of Seoul. I was curious about the opportunity to pose a generative formula based on how the physical environment and visual forms in the city had been created. Since most of the existing research on Seoul is based on its history, urban planning, or urban geography, urban discourse is also centred on scientific planning and abstract theories. Just as the European urban morphology investigates urban forms by tracking the evolution of buildings and void spaces, we also felt that we needed a theoretical approach to explain our urban morphology. Therefore, the concept of urban morphology in the West came to be used as a framework for interpreting Seoul.

Bang: I’ve felt that this book stands out in that it is by an architectural theorist who studied architectural history and theory and here presents his urban theory to identify the identity of the city. The nine keywords are proposed as concepts for analysing urban forms, but how were these keywords derived?

Lee: Since I received an architectural history major, it was not easy to determine how best to approach the city. Along with personal research, basic materials needed to support the writing of the book were collected while running school seminars with students over two to three years. By exploring western urbanism, particularly the books related to urban morphology, keywords that can explain Seoul’s urban form can be derived from the discourse naturally and intuitively. The ‘street-parcel-block, building, and area’ in the first part of the book is a basic element for western urban units, just as the alphabet forms the English language. The characteristic phenomenon of these elements operating in a special environment such as Seoul was summarised in Part 2 as ‘superblock, patchwork, and facility layout’. In the final section, Part 3, we looked at the problems of external space and nature, which are important elements in western urbanism, focusing on the keywords ‘street scenery, public space, and nature’.

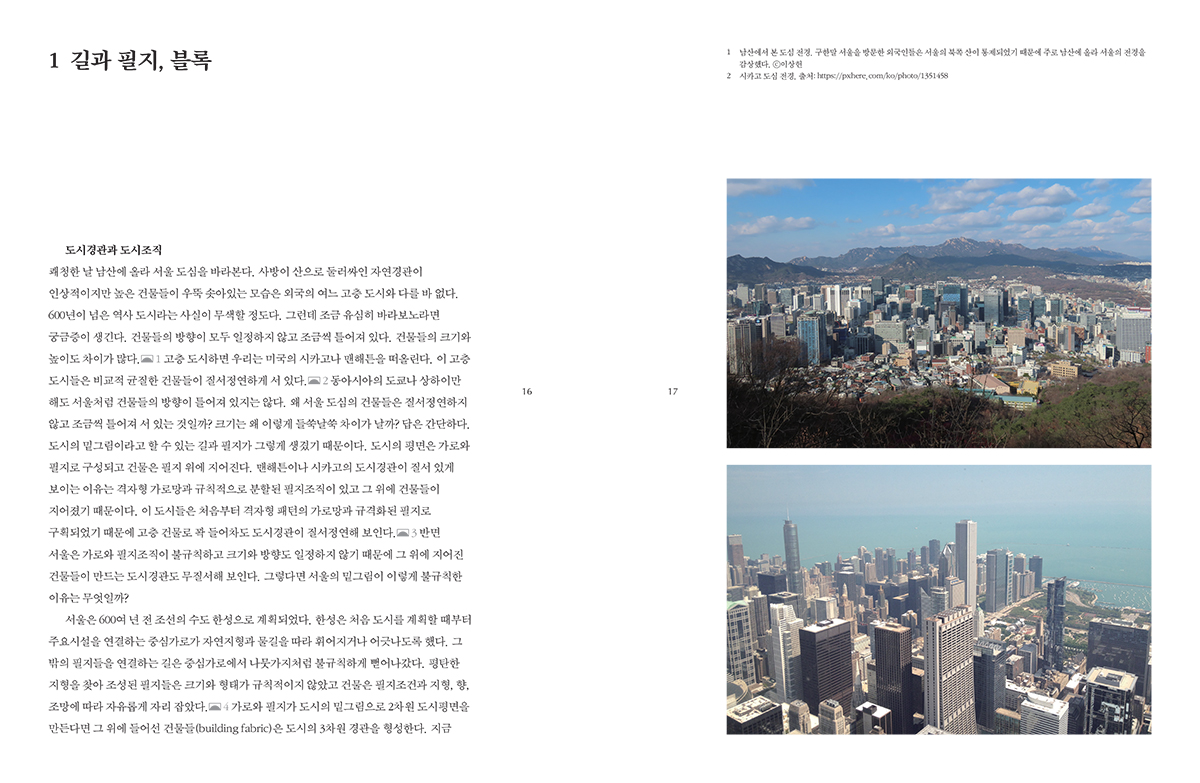

Bang: Part 1 compares the way streets and parcels are made and the way buildings are located in parcels with western cities, revealing the history behind Seoul’s urban structure and scenery which is fundamentally different to that of the story of western cities. It was interesting to see this conceptual systematisation of Seoul’s unique and defining elements.

Lee: Western cities have a long tradition in establishing a relationship between streetsand parcels, and between parcels and buildings. They gather to form blocks, and city blocks form

urban theories that comprise urban structural units. However, when we apply this concept into Seoul, we find very different aspects. For example, in European cities, long and narrow

parcels arranged along the street gather to form blocks, and buildings are built facingthe street to form a certain urban landscape. Such traditions are maintained even today. On the other hand, Seoul has long privileged the construction of irregular streets and parcels, and the parcels have never formed blocks. The urban landscape is also inconsistent because the layout (facing south) within the parcel was more important than the building facing the street. The characteristics of the parcel structure have led to building regulations such as building separation and diagonal restrictions in modern times, affecting Seoul’s urban landscape. By establishing fundamental conceptual differences, the characteristics and differences of urban forms could be explained more easily.

Aerial view of low-rise residential area in Jamsil, Seoul ⓒSanghun Lee

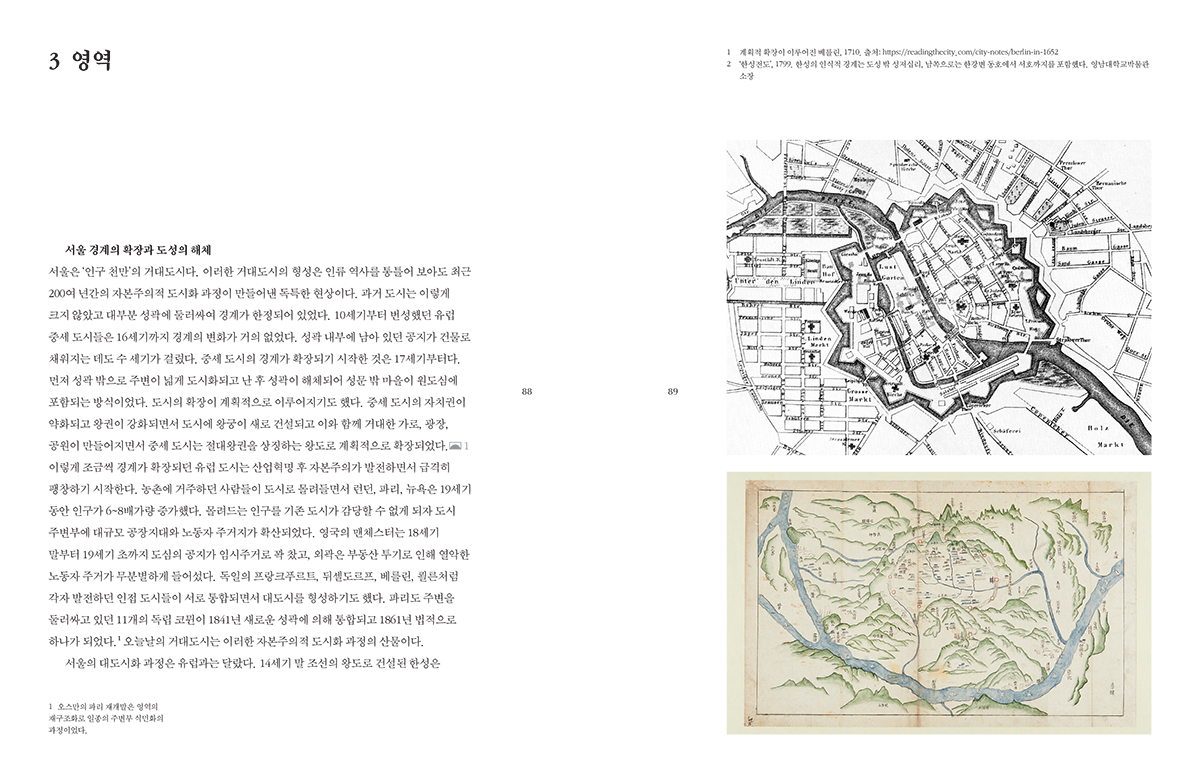

Bang: This book focuses on the 100-year history of Seoul, from the feudal period of Hanseong to the present day through Gyeongseong in the modern period. It is impressive that the project chooses not to look negatively at the modern city plan, as introduced by Japan during the Japanese colonial period, but instead to explain its achievements, its impact, and connections to the present.

Lee: The urban modernisation of Seoul was based on the urban planning carried out under the Japanese colonial period. The city plans introduced by Japan, including the Joseon Urban Planning Order (1934), Gyeongseong Urban Planning (1936), and land readjustment projects, had an impact even after the liberation of Korea. The development of Gangnam, which has been underway since the 1960s, can be seen as an extension of this development because it had no choice but to refer to Gangbuk. What is important here is that the Japanese plan did not completely ignore the city structure of Hanseong. For example, an unrealistic plan that does not match Seoul’s urban structure, such as the radial street system, could not be realised.

Bang: At the beginning of the book, you quoted Jacque Herzog who toured the Cheongdam-dong area in Gangnam, Seoul, and suggested that ‘Seoul is a city with no identity.’ However, after reading the analysis in Chapter 4 ‘Superblock’ and Chapter 5 ‘Patchwork’, I think that the hybridity and diversity that defines these coexisting extremes are an aspect of Seoul urbanism.

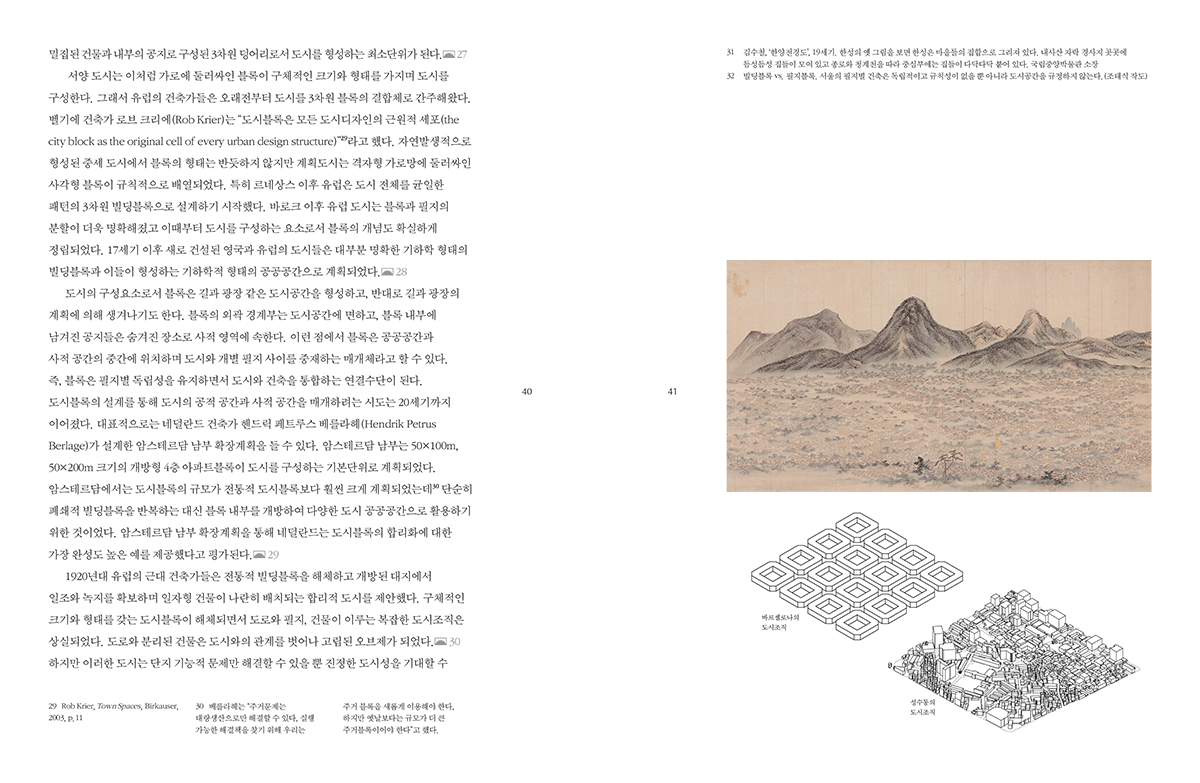

Lee: Western superblocks were made by combining several city blocks. Inside the huge block surrounded by roadways, high-rise buildings with their broad open spaces and pedestrian-centred spaces were installed. On the other hand, Gangnam’s superblock was created by the introduction of the grid-shaped highway network cutting through narrow pedestrianised streets and a more organic urban tissue with the spread of parcels. It shares the same name, but it emerged from a completely different approach. Broad roads ring the outskirts with their speeding cars while the narrow roads feature immense foot traffic. The coexistence of the speed and scenery at both ends could be thought to

be disorderly. The same is true of the large parcels inside the superblock fragmented like a patchwork or changing respectively. However, such complexity and autonomy can

be seen as creating Seoul’s unique identity.

Bang: You have been teaching architectural history at the university for more than 20 years. I wonder how the content and messages of the book come together for you in the educational field and how the students react to these ideas?

Lee: Unfortunately, I couldn’t give a lecture one this content alone. However, as part of teaching architectural history in schools we are trying to instill a fundamental awareness

about the city of Seoul and modern Korean architecture. In the modern architectural history class, which focuses on western architecture, I deliver lectures on how Korean architecture has changed over the past 100 years from the 1900s to the present. It reveals how we have digested and responded to the trends and theories of a passively implanted western architecture. This problem is ultimately linked to the identity and regional characteristics of Korean architecture. Looking at the report submitted at the end of the class, it seems that students also sense that the problems of the modern era have not been properly resolved.

Bang: On the other hand, do you think other cities in East Asia face similar problems?

Lee: Other large cities in East Asia are similar to us in that there is no clear morphological order. Rem Koolhaas named this kind of city ‘Generic City’. In contrast, however, many

studies have been conducted on urban forms in Japan, especially on parcel organisation, and there are many western scholars and architects who are interested in this. Barry Shelton, quoted in this book, is a case in point, also conceiving of the direction of future urban planning in Japanese cities. In comparison, we seem to be academically isolated. The biggest problem is the attitude of blindly borrowing from the eyes and mouths of western architects and scholars to explain our architectural culture to us and to cite them in reverse through their superficial observation and criticism based on impression. This poses a situation whereby there is no basis for explaining our architecture and city. Using an expression I deploy in the book, I wonder if ‘intellectual sadaejuui (snobbism)’ still permeates our culture.

Bang: Looking at the vast data sets used to support your claims and its detailed analysis, I found this book to be a collection of a scholar’s experiences and knowledge. You said you’ve now finished your homework, but I’m curious about your next move.

Lee: I would like to take a break now because publishing this book was exhausting! (laugh) If I write another book, I think I’m going to have to go back to my original field of study. University architectural history textbooks now use western architectural history. The university’s architectural history courses are also divided into western architectural history, Korean architectural history, and modern architectural history. Korea is the only place to study the history of architecture across three parts. No words can take the place of this. While everyone agrees that a fundamental shift in perspective is necessary, there is a lack of research to make this happen. If I had one personal desire, it would be to I write a history of

world architecture as we understand it from our own perspective. Doesn’t the focus of western architectural history vary from person to person? The United States claims American architecture as the mainstream, as do Britain and France. I think it is necessary to describe our own architectural history as a vital subject of study.

Images of Seoul Urbanism ⓒSPACE BOOKS