Image courtesy of Danish Architecture Center / ©Laura Stamer

SPACE September 2022 (No. 658)

There are people who claim that history is suffering from ‘amnesia’. They are individuals who question the story narrative in the history of architecture that ‒ while highlighting the life of a genius architect as someone who supposedly overcame all challenges and accomplished everything by themselves ‒ tends to dismiss the unmeasurable amount of contributions that people of various genders, beliefs, and backgrounds had put in to create a space for everyone. Diversity, consideration, and collaboration—these are words that are commonly emphasized by both the head curator of the exhibition ‘Women in Architecture’ in Danish Architecture Center and the collaborating archive team WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE 1925 ‒ 1975: A New History of Gender and Practice (hereinafter WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE). Let us hear their thoughts on the history of architecture and its narrative method.

Ragna Grubb (1903 ~ 1961)

Change of Direction for the Archive: Doubting the History Textbook Narrative

Interview Svava Riesto co-leader, WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE × Youn Yaelim

Youn: The research team WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE was established within University of Copenhagen in December 2020. As stated in its name and research theme, the team sought to uncover the narratives of female architects forgotten in Danish history. It is unexpected that this kind of research began in Denmark, which is one of the highest-ranking countries in the Global Gender Gap Index. What were the motivations that led you to develop an interest to this theme and embark upon your research?

Svava Riesto (Riesto): Like the other Scandinavian countries, Denmark is known as a place with a high degree of gender equality. But if we look for example at existing research on 20th century Danish architecture, it is remarkably gendered in that it focuses almost solely on men. Prior to the project, we studied the best-known books about 20th century Danish architectural history, and we looked at whose history gets to be told and whose does not. It was remarkable how many stories focused on a handful of famous men in design, and how few women were mentioned. We found some accounts of women’s history and we build upon these. Yet, much of the written architectural history of modernism is oriented around men. And it celebrates a patriarchal ideal, and values that are traditionally associated with the masculine—the ‘modernist hero architect’ who has seemingly made all these designs by himself. When we began to look more closely at how these buildings, cities, and landscapes came about in Denmark, we discovered that many more actors had contributed to this development—many other architect men and women that were later forgotten, as well as commissioners, builders, engineers, gardeners, politicians, residents, activists, bureaucrats, and others. We have chosen to follow women architects into the material to discover some of these complex and sometimes messy collaborations that reflect different power relationships.

Youn: One might say that this is a project that began by placing an interest on matters beyond the history textbook. Perhaps this explains why the expression ‘a more comprehensive history of architecture’ appears often in your project introduction.

Riesto: Yes, we want to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of Danish architecture history. In light of the many crises we are facing today we need other histories of architecture, in order to find out what role architects can play in the present and in imagining other futures. In this way, our project is not only about discovering forgotten women but also about helping to redirect the understanding of how our built environments have been shaped, focusing on collaboration, diversity, and care—all core values for future practice. We do so because we believe that collaborative and inclusive forms of work will be key to dealing with the challenges we face today and shaping more just, equitable, ecologically sound and inclusive futures.

Youn: It is curious that the team was formed not within a department of architecture but one of landscape architecture. I would like to know how this came about.

Riesto: The practical reason was that Henriette Steiner (co-leader, WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE) and I both already worked here when we embarked upon the project. However, being based in a section for landscape architecture and planning turned out to be an interesting vantage point for the research. Many people would expect such a project to be oriented to the scale of single buildings, or maybe urban design. However it was typical during this period of Danish design for architects, landscape architects, urban planners, and a whole range of other professionals to work closely together to shape environments where interiors, buildings, urban spaces, gardens, and large park systems and designed landscapes were closely interrelated. We considered it important to begin to uncover and understand how women from different professional backgrounds because they all helped to shape the new modern buildings, cities, and landscapes of the Danish welfare state operated in this field.

Youn: What is the criterion behind the specific range and setting for the archive? The research theme has been narrowed to female architects from 1925 to 1975, but I assume that the trend of neglecting female figures in history was not restricted to just this period.

Riesto: Yes, that is certainly the case. The topic does not concern only Denmark or only this period. As historians, though, we need a working scope that enables us to go into things in depth and understand specific historical contexts. So, we chose to focus on women who operated or were educated in Denmark. However, we also acknowledge that when we begin to follow the individual lives of these women, they traveled across national borders, had exchanges with people in other countries, participated in international networks and discourses. We chose to begin our study in the 1920s because this is when we begin to see not only individual women but a slowly growing number of women entering architecture and landscape architecture education in Denmark. The subsequent 50 years were an amazing period, when women entered the field in ever greater numbers, and also when much of modern Denmark was built. Things began to change a lot during the 1970s ‒ with so many new initiatives from feminism and other new social movements in architecture ‒ so we end our story there for now.

Youn: The project aims to propose an ‘alternative archive’. What are the differences between this archive and the original archive?

Riesto: Well, if we look at institutional architectural archives, they tend to rest on the tacit assumption that men’s work is much more valuable than women’s. There has not been an explicit plan to exclude women, but it has come about as a result of many different factors and traditions in terms of how to collect materials. For example, the archives of architecture and landscape architecture drawings here in Denmark have routinely collected the work of professors and the lead designers in big studios and these positions have mostly been held by men. Other areas of work where we find more women – such as the work of employees in the design studios, municipal planners, teachers and others – have not that often been collected in official architectural archives. But it is often possible to find this kind of material, if you look beyond the architectural archives: in municipal archives, in women’s magazines, and among women architects’ children, former employees, siblings, or friends, who may have found material in an attic or a drawer, and so on. What we do is make this material visible and to engage with it to write new histories.

Youn: With the archive at the centre, the project has also extended into publication, exhibition, education, and a podcast. How do these projects across various media platforms complement one another—and if they share a common goal, what is it?

Riesto: We want to tell these stories in new, more engaging, and more inclusive ways that is not only relevant to specialised historians. Therefore, we have engaged with the public right from the start. We have felt an ethical obligation to share our results and methods, because we see that students, architects, and people with a general interest in gender are eager for this kind of information. Further, sharing has been part of our method because it has enabled us to get feedback, ideas, and tips along the way. The other day, a man called us to share material about a building in his neighbourhood that was designed by a woman we didn’t know, but then chose to study more closely. Others have written and offered us invaluable archival material that they found in their late grandmother’s attic. We have created contacts between official architectural and landscape architectural archives and relatives who think that such material can be included into the archives. This kind of ‘archivism’ and dialogue has made our work very rewarding and a lot of fun.

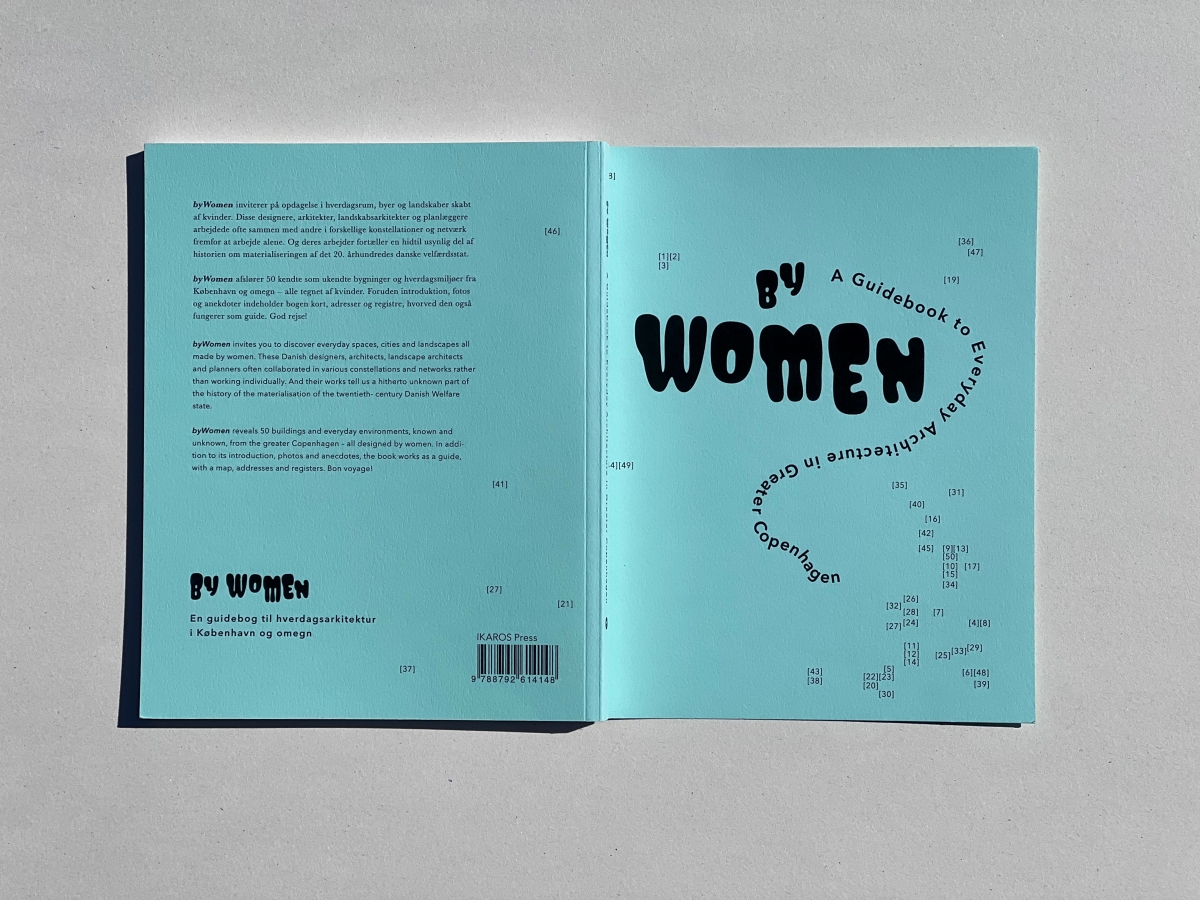

ByWomen: A Guidebook to Everyday Architecture in Greater Copenhagen (Ikaros Press, 2022)

Youn: Going beyond the 20th century, I would like to know more about the contemporary situation for women in the Danish architecture scene. In the case of Korea, the percentage of female graduates from architecture department is relatively high compared to other engineering departments, but only about 10% find a job in architecture.

Riesto: Where I teach—the landscape architecture education at the University of Copenhagen, almost 80% of the students are women. And we have seen more women than men in the schools of architecture, too. Yet, we still see more men than women in leading positions in architecture in Denmark. But this has become a growing issue in the last couple of years, and many of the educational institutions have begun to work on how to change things. If we want our buildings, built environments and landscapes to work for all, we need many different identities to engage their knowledge and experience when shaping them.

Youn: In a recent archive workshop, you asked, ‘What might a feminist archive be?’ I would like to know if you found the answer to that question—or if this is still ongoing, in what ways are you searching for it?

Riesto: This question has been important in feminist scholarship and activism for decades, and it is becoming increasingly urgent now—not only in Denmark, but in many different contexts. I think one of the most important things is to recognise that archives are not passive containers of material that self-evidently reflect ‘the past’, but that they are made. Someone has decided what goes into the archive and what does not and how this material is then systematised, categorised, and maintained. This means that we can critically question the archive as a place of values and politics. But more than that, a feminist archival practice is hopeful because it allows us to expand the archive, redirect it, and make room for other voices, documents, and stories. For example, by beginning to make room for the work of women in architecture, landscape architecture, and planning, as we do in this project. Or by including the voices of local residents in stigmatised social housing area, as I am doing in another project. It might be about indigenous groups or people in refugee or other situations, or other groups that are often marginalised in history and who have less of a voice and power. Or it might be to say that objects that have traditionally been seen as private or other media like oral history interviews, take a new place in the archive. The important thing, I believe, in feminist archival work is that we need to continuously question what the archive does and what it can do in terms of providing more inclusive histories and ways of understanding design practice.

Group photo of WOMEN IN DANISH ARCHITECTURE / ©Maja Flink