SPACE October 2022 (No. 659)

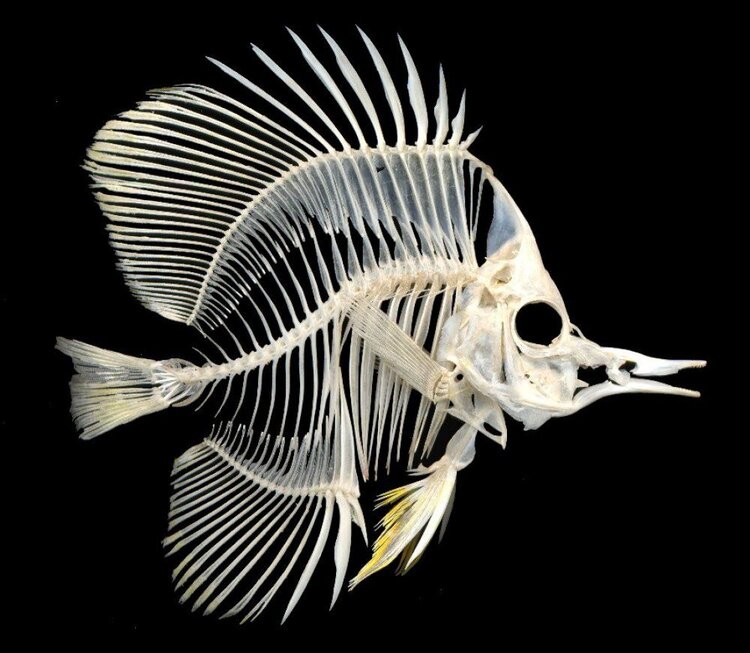

Tonkin Liu draws inspiration from nature. The aspects of nature explored here are divided into climatic elements such as light and wind, topographical elements such as mountains and rivers, and biological elements such as shells and marine life. Most particularly the Shell Lace Structure, a structure inspired by the evolution of shell, is noteworthy in that the characteristics of a shell constitute both design and structure. Here, we hear from Tonkin Liuʼs co-principals Mike Tonkin and Anna Liu about how our vibrant, evolving, and limitless natural world can meet and merge with architecture.

Sun Rain Rooms / Image courtesy of Tonkin Liu

interview Mike Tonkin, Anna Liu co-principals, Tonkin Liu × Park Jiyoun

Park Jiyoun (Park): Tonkin Liu classified the ways in which architecture approaches nature into three different categories.

Mike Tonkin, Anna Liu (Tonkin, Liu): Nature can be found in our work along the three lines described. These three layers represent three lines in a timespan, from our current moment, the passage of time, to ancient myths, across 500 million years of evolution. First, what weather offers generously for free, sunlight, rainfall, wind, and animate architecture, make us keenly aware of the passage of time. Secondly, powerful symbols, such as mountains, rivers, flowers, and oceans have, since the onset of human civilisation and story-telling, connected human beings to our identity and our land. Thirdly, design exemplars in nature, form, integrated systems, and principles, teach us to design responsively, iteratively, adaptively, inventively, holistically, and to aspire to use very little to achieve a lot.

Park: In Sun Rain Rooms (2017), the roof was designed to take into account the sun path in order to maximise natural light, and the drainage system was planned to collect rainwater into the pond in order to provide it to the plants in the courtyard. In fact, these methods are more often used in eco-friendly design. Is there any part that Tonkin Liu would consider a specialism?

Tonkin, Liu: By embedding nature into architecture, we are in effect animating architecture with light, patterns, textures, colours, movement, and seasonal changes. In effect, we are infusing architecture with an acute awareness of the passage of time: a day, a week, a month, a season, a year. The fall of the rain, the arc of the sun, the wind, all take centre stage in the architecture. As eco-friendly architecture, designs should not only harness the power of nature but also use nature’s sensory powers to touch people’s hearts and minds.

Park: Cradle Towers (2016 – ) in Zhengzhou used the nearby Songshan Mountain as a design element. How is this form combined with its function?

Tonkin, Liu: To embark on a design is to embark on a journey that is both intuitive and rational. In being given the brief of five towers – three residences, one hotel, and one office tower – we explored alternative typologies for how a community might live together and occupy an entire urban block in a grid, in the heart of the city of Zhengzhou. Our exploration was done both by hand and digitally, through plasticine models and computer 3D models. We tested a diverse range of dispersed typologies and concentrated taller tower typologies. In parallel, we immersed ourselves in clues, which included the Songshan Mountain landscape, the chinar trees, and cultural communal traditions such as teahouses. We always enjoy designs that create a holistic entity. The established architectural logic comes from inhabiting the entire city grid perimeter to create a generous community courtyard and garden, growing the corners to create five towers, reaching like fingers in the air, and then joining the five towers at their podium base, which optimises the structure to land relationship more easily, as if buttressed trees. We then cut into these to create green canyons, bringing light and air into the base of the towers.

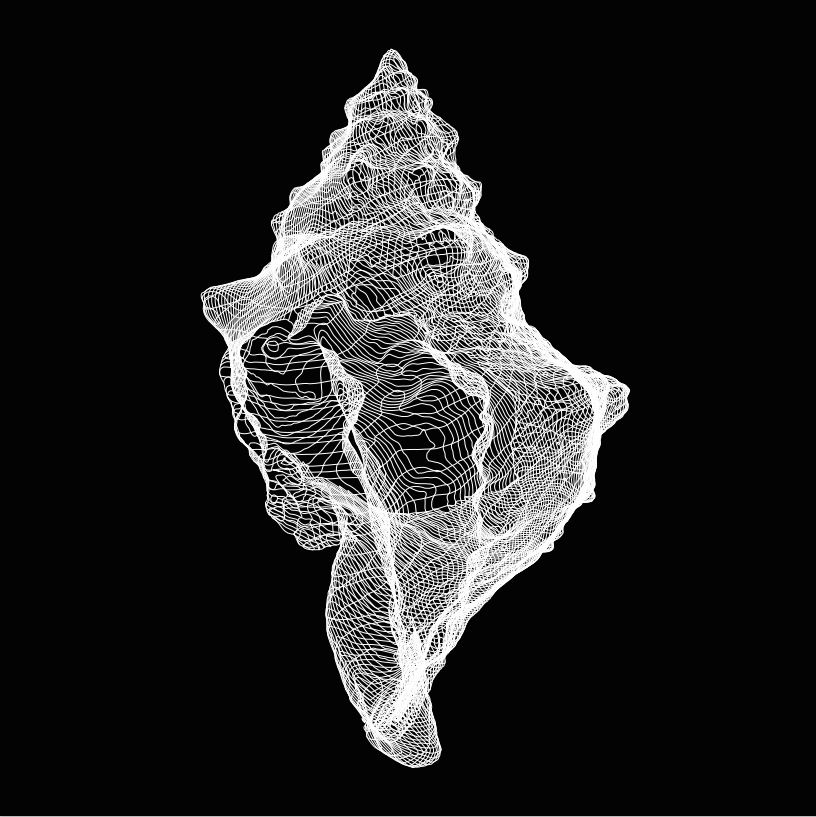

Park: From now on, let’s focus on the Shell Lace Structure, a method of imitating nature, as well as projects that used this method. The Shell Lace Structure is a prototype for a ‘single surface structure’ in which the surface becomes the structure, imitating the shape of a shell. What was the background to this and what desires prompted the idea?

Tonkin, Liu: It was through one of these design competitions, for a seaside pavilion for which we researched and played with the structural characteristics of mollusc shells, that we invented Shell Lace Structure as a technique. The intuitive process of exploration through models led us to a pavilion structure that was incredibly lightweight and strong. We decided, though not succeeding in this competition, that we would not give up on the technique. Together with structural engineers at Arup we decided to enter another competition, for the design of a bridge in Lisbon. Although this was a horizontal structure, we applied the same structural principles: curvature, corrugation, and distortion. These geometric principles gave us super strong structures. The second aspect of this invention was the hybridisation with the ancient technique of tailoring. All of the Shell Lace Structure works are fabricated from flat sheet materials, be they cardboard, aluminium, steel, or timber sheets. Like a tailor’s cutting pattern, the cut flat pieces are then connected at the seams and form a strong, stiff, three-dimensional form.

Shi Ling Bridge / Image courtesy of Tonkin Liu

Park: You have derived properties such as curvature, corrugation, distortion, and beading from the forms and appearance of a shell. How does each element function in the building?

Tonkin, Liu: These three attributes work together to enable us to create structures of large spans using very thin sheet materials. In doing so, we minimise the dead weight of the structures, the needed foundation, and the usage of materials. We then perforate the structure as much as possible. This final step removes weight where the structural stress is least, it shows off how thin the sheet material is, lets light through and creates dappled lights.

Park: Did you face any problems throughout the series of processes such as sheet cutting, unit transportation, and on-site welding?

Tonkin, Liu: This is an important point. Without actually fabricating and delivering a project, we would not have learned certain invaluable lessons. For Rain Bow Gate (2012), we learned three lessons: modularity, transportation, and bolting on site. The 3mm thin, long flat steel sheets were very floppy to handle, so required a timber framer to drape the cut sheets over. The timber framer was costly. Therefore, for another project, this time, a larger building, we standardised the geometry so that the entire building could be made with two types of modules and we can use the same formwork repeatedly.

Park: Various materials, such as aluminium, steel, and medical silicon have been used. What are your criteria for selecting materials?

Tonkin, Liu: Context, cost, and maintenance are all important. The seaside environment called for a weatherproof, self-finishing material. Hull was also not far from the waterfront, but here we were building a much larger structure and were trying to minimise cost, so we opted for steel painted with polysiloxane paint which allowed for future small area touching up, if required, without having to repaint the entire structure.

Park: Shi Ling Bridge (2009) is a 75m long bridge that crosses a valley. There must have been structural difficulties due to the site conditions and the project scale.

Tonkin, Liu: This was a hypothetical project which Arup invited us to take part in, on the topic of the ‘Bridge for the Future’. Here again, the structural and sculptural exploration was enacted through plasticine. Using simple structural types such as the torsion beams, we wove three together that would rise up and deepen as required, and dive down to form a composite column. Here the digital computer model met its limitations. We could not resolve the junction at which the three torsion beams were to merge; it seemed far too complex in the digital model. So, we used different colour plasticine models again. The final result is another very efficient structure: the 75m span is achieved with a 16mm thick steel structure.

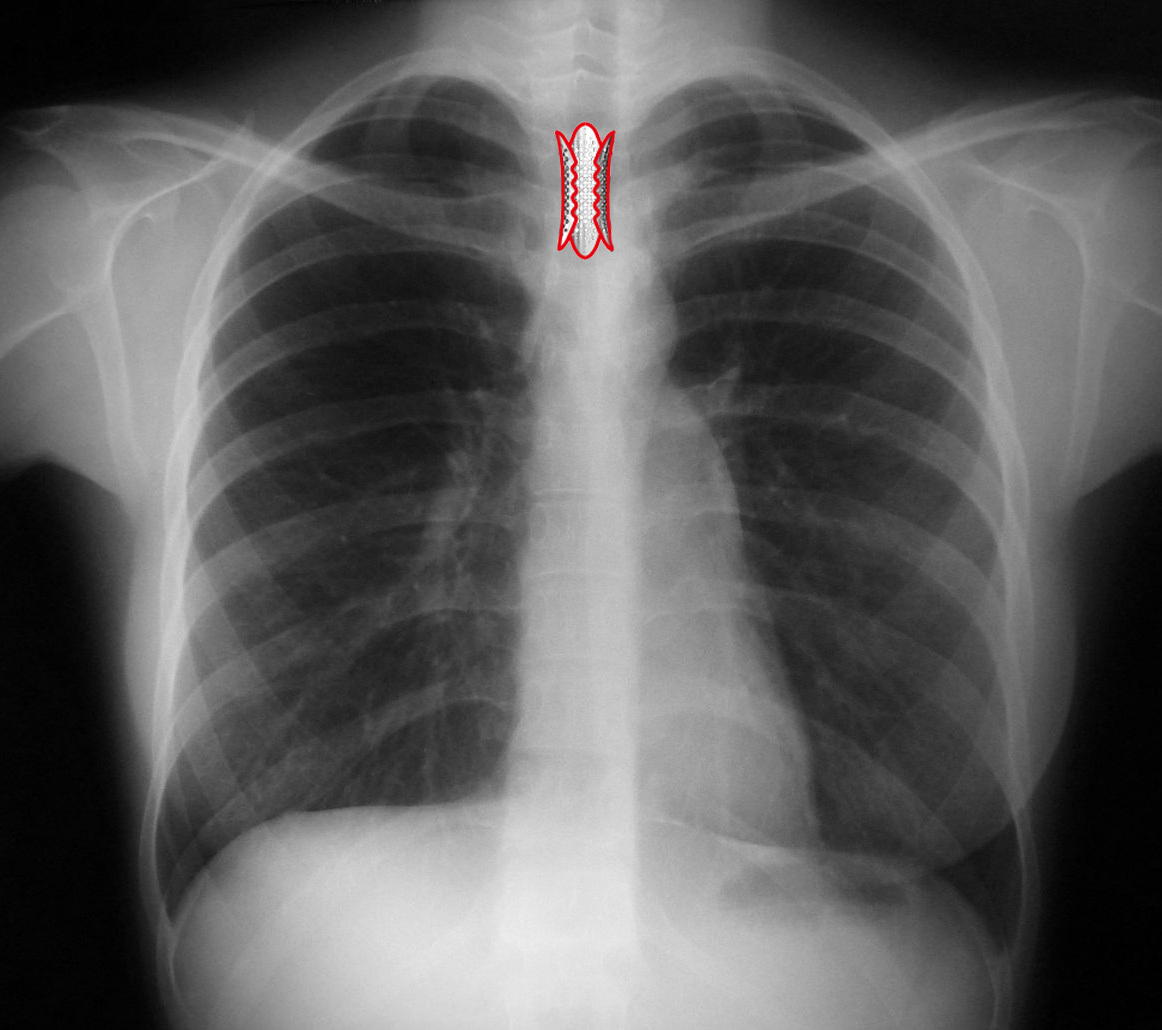

Shell Lace Stent / Image courtesy of Tonkin Liu

Park: Shell Lace Stent (2021) is a medical device that is used for treating throat cancer, which is inserted into bronchial tubes. I would like to know the reasons and intentions behind creating a Shell Lace Structure suited to the human body.

Tonkin, Liu: Through our Shell Lace Structure projects, we have become very knowledgeable in terms of using geometry to gain strength. The Shell Lace Stent was designed with this knowledge, both at the macro scale (the overall curve of the tube achieving the desired push-out force), and at the micro scales (local turns and undulations adding stiffness). In 2014, we gave two talks to accompany the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) exhibition we held for ʻThe Evolution of Shell Lace Structureʼ. At one of these talks we were approached by a medical researcher, who had envisioned the technique as applied to the design of an airway stent, her particular area of specialisation. We joined forces with her medical institute, Arup, and applied for the Innovate UK funding, in which we succeeded.

Park: In terms of imitating nature, what do you think is the methodological value of the Shell Lace Structure?

Tonkin, Liu: Shell Lace Structure demonstrates how one should imitate nature not literally, and through a creative process of observation, modelling, learning empirically, abstracting a set of principles. Nature should not be imitated in a sentimental and undigested way, which often leads to biomorphic and biomimetic projects that are costly to build, wasteful, wilful, and do not make structural nor environmental sense. Shell Lace Structure combines advanced digital tools in modelling, analysis, and fabrication with the craft of tailoring, and with an intuitive understanding of structures.

Swing Bridge / Image courtesy of Tonkin Liu

Park: Regarding nature, I would like to know if there are any other structural ideas that follow the Shell Lace Structure?

Tonkin, Liu: The natural world continues to inform our work in multiple ways, in addition to that of Shell Lace Structure. We recently completed Swing Bridge (2021), which also drew strength from its form. The three innovations were the central pivoting that provides access control, the undulation in the balustrades, and the laser-cut comb construction technique.

Park: In addition to the methodology, I would also like to ask you about your attitude. There are many different kinds of attitudes towards dealing with nature, such as the conservation of nature, use of nature, and a symbiosis with nature. What is Tonkin Liu’s attitude towards nature?

Tonkin, Liu: Complete symbiosis with nature. As we discover more and more about the intricacies of nature, I am increasingly filled with a sense of awe and wonder for the natural world. Digital tools have made legible, visible, quantifiable, nature’s inter-connected systems and the scale of our impact on them. We now understand the devastating effect we’ve had on the planet. The industrial era only scratched the surface of the intelligence and diversity of nature, and was unfortunately motivated by the conquest and commercialisation of nature. The digital era has broadened and deepened our understanding to a vast degree. Furthermore, digital tools will enable our actions to be much more in sync and in tune with nature―intelligent, targeted, with longevity and with wisdom. We have been given a tremendous gift: a vast quarry of newfound intelligence on nature’s ingenuity. We have a responsibility toward this gift, and should be emboldened and inspired to find solutions to the environmental crisis.

Rain Bow Gate / Image courtesy of Tonkin Liu