SPACE April 2022 (No. 653)

The solo exhibition ‘Homo Natura’ by Song Sanghee, which was on show at Seoul Museum of Art, came to an end on the 27th of February. As the winner of the of The Hermès Foundation Missulsang 2008 and the Korea Artist Prize 2017 at National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Song is not a newcomer to the contemporary art scene as a media artist. Song focuses on presenting the silent voices of people across known sites of natural disasters, acts of terror, war, and genocide that had either been forgotten or ignored, and this solo exhibition – the first time she has exhibited her work alone in a national museum in Korea – marks the end of a 20-year hiatus in her practice, returning with a more refined and elaborate outlook. This omnidirectional project, which crosses the boundaries of certain media and collates various spatio- temporalities and histories under the theme ‘Homo Natura’, now takes a bold step forward. I had the opportunity to ask her about the message contained in this 75-day exhibition, by covering her artworks one-by-one.

interview Song Sanghee artist × Bang Yukyung

Exhibition view

Bang Yukyung (Bang): This exhibition is your first solo exhibition since the Korea Artist Prize 2017. Did something change in your work or in your thinking following that exhibition?

Song Sanghee (Song): The exhibition at MMCA was described as one that ‘embodies the voices of people who cannot partake in public discourse and are forced to disappear by the existing power structure’, and I felt ashamed of this claim. In reality, I find it difficult to empathise with the people who are close to me, let alone with those I do not know. Upon returning to my workroom at Amsterdam after the exhibition, I felt as though the voices that I kept deep within myself had suddenly been spirited away, leaving me by myself alone. Then the many ‘I’s’ within me started to interrogate me, asking ‘do you have the right to continue this work?’. In the search for the definition of these numerous ‘I’s’ within me that hurt others and are motivated by greed, I started reading. It was at this point that I came across the phrase homo natura in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. I realised that the doubts and questions that began with the sense of ‘me’ as an individual coincided with the contradictions that define this world, and that a human being cannot simply be explained by the easy binaries of good and evil, true and false. I wanted to invite viewers to confront their ‘terrible basic text’ and expose the contradiction and irrationality threaded throughout the individual and their society. This is how I came to decide on the title ‘Homo Natura’—I began noting down the exhibition plan in 2019.

Bang: In your descriptions, you reveal the details of your extensive reading and research across genres. I’m curious to know more about your working process: how do you develop and arrange all of these ideas into complex layouts that use various media?

Song: When an idea or theme surfaces, I collect papers, books, newspaper articles, and data sets to gain various perspectives on that issue. My working process is the process of grasping nothings, like getting lost in a fog. So I came to conclude that reading should be done like the writing of a diary, and so I write down the book title and date as I make citations, and I organise them into folders according to the year. After finishing the data collection process, I choose the format and medium ‒ drawing, photograph, video, performance, or others ‒ that fits the idea. When I take a video, I also decide the resolution, gear quality, and so on, to match with the content.

Bang: The installation work The Song of the Earth (an archival collection of videos) reflects this approach very well. For example, in Mohang, you installed cameras on the left and right side of the boat to capture the seacoast of Taean county following the oil spill incident. Similarly, you attached a camera to your foot as you walked a trail of Mt. Osore as reparation for souls for the children who had died before their parents during the World War II, and you tied the camera to the end of a long stick to capture the mango tree forests in Bagamoyo, Tanzania and the Canary Islands.

Song: This work is a project that began in 2012 when I learned that the mango tree of Tanzania is a historical trace of colonial activities and the slave trade. It dawned on me that people may die and pain may subside, but the natural realm ‒ the grass, stones, wind, and the sky ‒ may still bear the traces of what happened there. From then on, I took the appropriate video equipment along with me on all my visits to places with painful pasts, such as those afflicted by natural disasters or acts of genocide to capture the scene from nature’s perspective. In that context, the seacoast by Taean county was taken from the perspective of a fish, the mango tree at Tanzania was taken from the perspective of a bird, and the brussels sprout farm affected by air pollution from a fire accident at an adjacent chemical factory was taken from the perspective of a sprout by rolling a camera kit in the shape of a ball to capture its persepctive.

Still images of the video The Song of the Earth (2021)

Bang: The locations that act as the background for your works ‒ Chernobyl in Ukraine and Verdun in France, for example ‒ are all places scarred by colonial rule, war, terrorism, genocide, and environmental destruction. What made want you to look at such places?

Song: When I was taking part in a residency programme at Sapporo in 2003, I took a trip to Hokkaido. On that trip I happened to visit Cape Sōya, located at the northernmost corner of Japan. It was a site to commemorate a terrible accident during the Cold War, in 1983, when the Soviet Union mistook a passenger-plane Korean Airlines flight 007 as an enemy plane and shot it down, killing everyone on board. It reminded me of the vivid scenes that I watched on TV as a child, with bereaved families crying their hearts out. I was struck by the thought that I should do something for the victims that had been laid to rest in the area. On my next visit to Japan some years later, I visited various sites with tragic histories, and I came to realise that the Japanese people, whom I had simply defined as the victimizer were also victims themselves, and that there is a web-like connection between the violator and the violated.

Bang: As a follow-up to this project, Geegers, You and I is a video work that documents the locations depicted in postcards developed by different colonial masters that ruled over Indonesia and Korea during the early 20th century. The clear-cut division between the victimizer and the victim that is often presented in contemporary history, and which developed in the wake of colonisation, dictatorship, and democratisation, is here either reversed or blurred to oddly overlap with the ways in which the present urban landscape and the old postcards are projected into one another.

Song: As I now live in the Netherlands, I naturally developed an interest in Indonesia which used to be a Dutch colony. The New World is a work that began with this awareness of themes related to colonial rule, domination, and exploitation. I expressed the metaphoric motifs of the trade war and the founding of colonies ‒ both instigated by human desire to conquer ‒ into three respective forms: a Delft blue tiles mural (Spirit and Opportunity), six pencil lightbox drawings, and bonsai plants. The forceful removal of Buddha’s head from the statue in Borobudur Temple located at Indonesia’s Java Island by the Dutch, so they could exhibit it in their national museum, and the destruction of the ancient temple ruins of Palmyra at Syria by ISIS— how different are these acts? This is also ultimately connected with the ways in which humans try to control nature and chart the planets in space. We say that these endeavours are performed for our betterment and the promise of our own survival, but from nature’s perspective, it is nothing but terrorism and violence.

Bang: In The New World, you used Delft blue tiles ‒ which are unqiue to the Netherlands ‒ which you first showcased in the MMCA exhibition. You created a huge mural composed of 80 pieces of 20 × 20cm square tiles. What were the intentions behind this piece?

Song: As I was preparing for the exhibition at MMCA, I came across a photograph of an explosion in a news article that was reporting the civil war in Syria, and I felt that this tragic incident was being reduced into a mundane image. By selecting the ‘blue’ colour from Delft blue tiles and the ‘grid’ as form, I expressed an explosive scene in a pixelated manner. For this exhibition, however, I focused on the fact that tiles are traditionally materials used in murals throughout Europe. The royals or the rich had beautiful, mythical or historically-important figures and sacred images drawn onto Delft blue tiles to form in murals. In this exhibition, I filled the tiles with various images representing the history of domination and exploitation, such as sugar cane, pepper, smallpox, slaves, Hermes, dodo bird, elephant tusk, the military satellite Milstar, and so on. The idea was to expose the distorted sense of greed and superiorities of human beings.

Mural Spirit and Opportunity of The New World (2021)

Bang: The New World draws together various stories, while the three-channel video work Apple puts together three episodes that reveal the errors and contradictions of dualism under the motif of an apple. These stories are delivered through the use of video imagery and subtitling that are loosely divorced from one another and yet also tightly connected to one another is quite persuasive.

Song: The beginning of Apple is the story of the forbidden fruit. By collecting various stories related to the apple, which had come to represent the forbidden fruit of Biblical teachings and the Medieval Ages, I wanted to show how things such as truth and falsehoods, good and evil, pleasant and bad are rather flexible terms that may change according to era and situation. In this vein, I tied together the recent reappraisal of the mathematician Alan Turing, who was condemned as criminal due to his homosexuality despite being a war hero who cracked the Nazi code in the World War II, along with the story of Snow White who was revived after dying from eating the poisoned apple. Likewise, Galileo’s heliocentric theory, which was once denounced as heretical but now considered to be truth; Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer, who ‒ despite having led the development of the atomic bomb in the US ‒ turned into active opponents upon realising its danger; the story of Gregor Samsa who turned into a bug overnight and was killed by an apple thrown by his father in Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis: all revolve around the theme of the ‘apple’.

Bang: Referring to your methodology, reassembling various narratives using a personalised grammar, the curator of this exhibition described you as a ‘digital quiltmaker’. This is especially prominent in the harmony shown between your use of video imagery, subtitles, and music. What have been your influences?

Song: I very much enjoy watching silent films from the 1910 ‒ 1920s such as ‘Faust’ at a theatre in Amsterdam, where I now live. The background music connects the flow of emotions, while the story is delivered solely via video and subtitles. I think I picked up this visual grammar from watching silent films: connecting music, video, and subtitles organically, while introducing changes in the mood and situation by using the gaps between those elements.

Three-channel video Apple (2021)

Bang: If I were to pick the most memorable work from this exhibition, for me it would be Dream. Objects that represent cases of social murder, such as the fire incident at the Gukil Gosiwon and the death caused by a screen door at Guui Station and others have been installed all around the exhibition hall. These objets appear unexpectedly, in real spaces like the gosiwon and metro station in the video Dream to form a mutual connection. Perhaps it could be compared to the movie The Avengers where heroes from the ‘Marvel Series’ with their individual stories come together in synergy. In terms of the connection and expansion of media, it was the perfect representation of transmedia storytelling, and it was personally fascinating as it seems to implicitly suggest a change in the direction of your work.

Song: Dream reveals the sacrifices of others that we have forgotten, the burden of hard work and the lived experience that each individual has to bear, and the proximity of hell to reality. The regrets and guilts that we all bear don’t vanish over time but become ever sharpened while concealed deep within our memory. One could say that the object and video of Dream are such feelings that, while manifested as physical things in the present exhibition hall, are simultaneously things that occupy a different temporality. The video begins with An Gyeon’s Mongyu dowondo, and C’est si bon’s song ‘Day Dream’ plays in the middle. By connecting the perspectives of past, present, and future, I wanted to ask if our unfulfilled dream of utopia is nothing but a daydream.

Still images of the video Dream (2021)

Bang: The exhibition concludes with Talk to You. Six drones spin and hover in the air asking, ‘Who are you?’, which is then answered by a video on the screen. I saw the disconnected individual who ‒ despite the discrepancy between the question and the answer ‒ is ever striving to communicate.

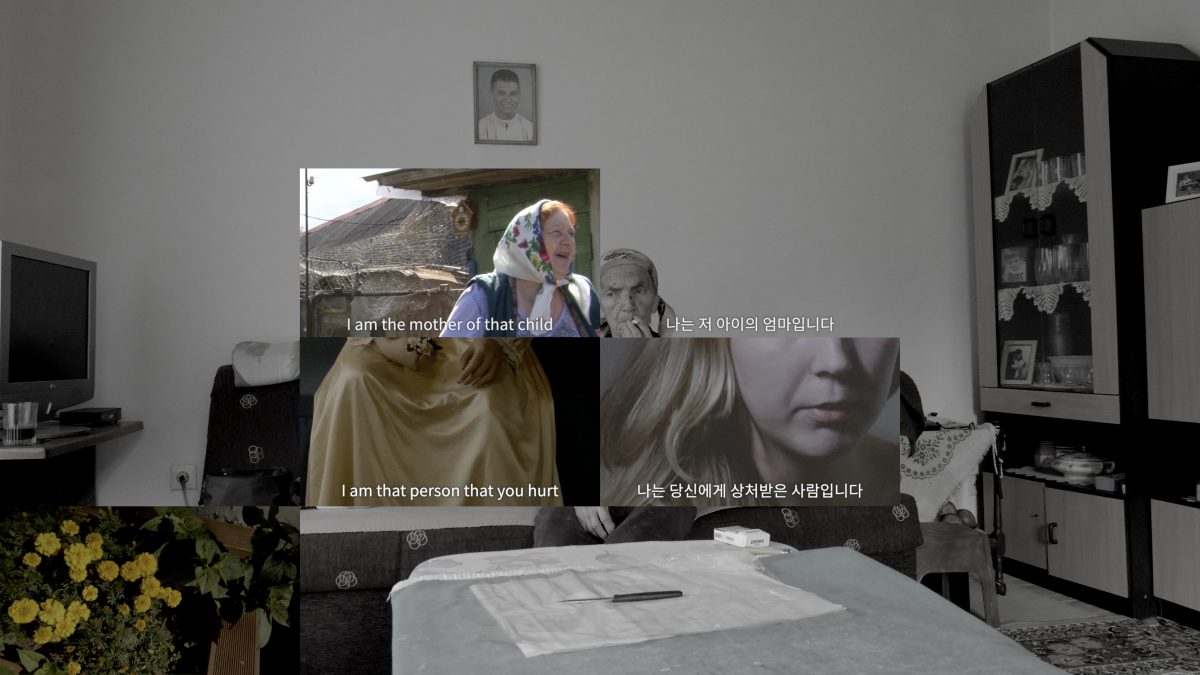

Song: Talk to You is a work that embodies the question ‘Who am I?’. While living in the Netherlands, I was often asked, ‘who are you, where do you come from?’. As my living environment had changed, I realised that the perspective I had towards myself had changed as well, in line with the relationships that I established around me. The work Talk to You plays a video depicting various sites stricken by civil war, terrorism, and conflict, while phrases such as ‘I got hurt by you’, ‘Why did you do that to me?’, ‘I can only understand myself through you’, ‘I got to know myself through your question’, and others flash on the screen. I felt that I could only be defined through the interpersonal relationships I forge within society.

Bang: If it could be said that the focus of your exhibition at MMCA was the ‘subject’ of the voice that you wanted to bring to attention. This exhibition emphasised the ‘attitude’ and ‘method’ through which one may virtually expand and amplify the master narrative. I’d like to hear your thoughts after finishing this exhibition, one that covers approximately 20 years of your own creative journey.

Song: I think this year marks an end of a chapter in my life. Two days ago, after finishing the exhibition, I went to clean up the workroom that I had been using for the past twelve years. As I was packing, I discovered a news article that I pinned on the wall as drawing material for On My Shoulder. It was a photo of a black man carrying a white man who was injured during the Black Lives Matter movement. The heart to respect and the need to save another human being in spite of such a climate of hatred seemed to me like a kind of an instinctive reaction. I think this resonates with John Berger’s To the Wedding that I cited in the work Talk to You. On the surface, it may seem like a Shinpa expressing unyielding love, but we are living in an era in which we cannot communicate with the world unless we strive to empathise with the sufferings of others. As an artist, I wish to work towards the attempt to come to greater understanding of others.

(top) Still image of the video Talk to You (2021) / (bottom) Exhibition view