SPACE August 2022 (No. 657)

The Davidson Prize, which marks its second anniversary this year, is an award given through a public contest for architectural ideas established in honor of British architect Alan Davidson. The theme of the 2022 Davidson Prize was ‘Co-Living – A New Future’, which was presented with a variety of future-looking ideas through the design of a living space together, and in June, it announced the final winner of the Charles Holland Architects, Quality-Off Life Foundation, and Sound Advisory. We hear about the themes and the meaning of the ideals that the just-launched Davidson Prize explores.

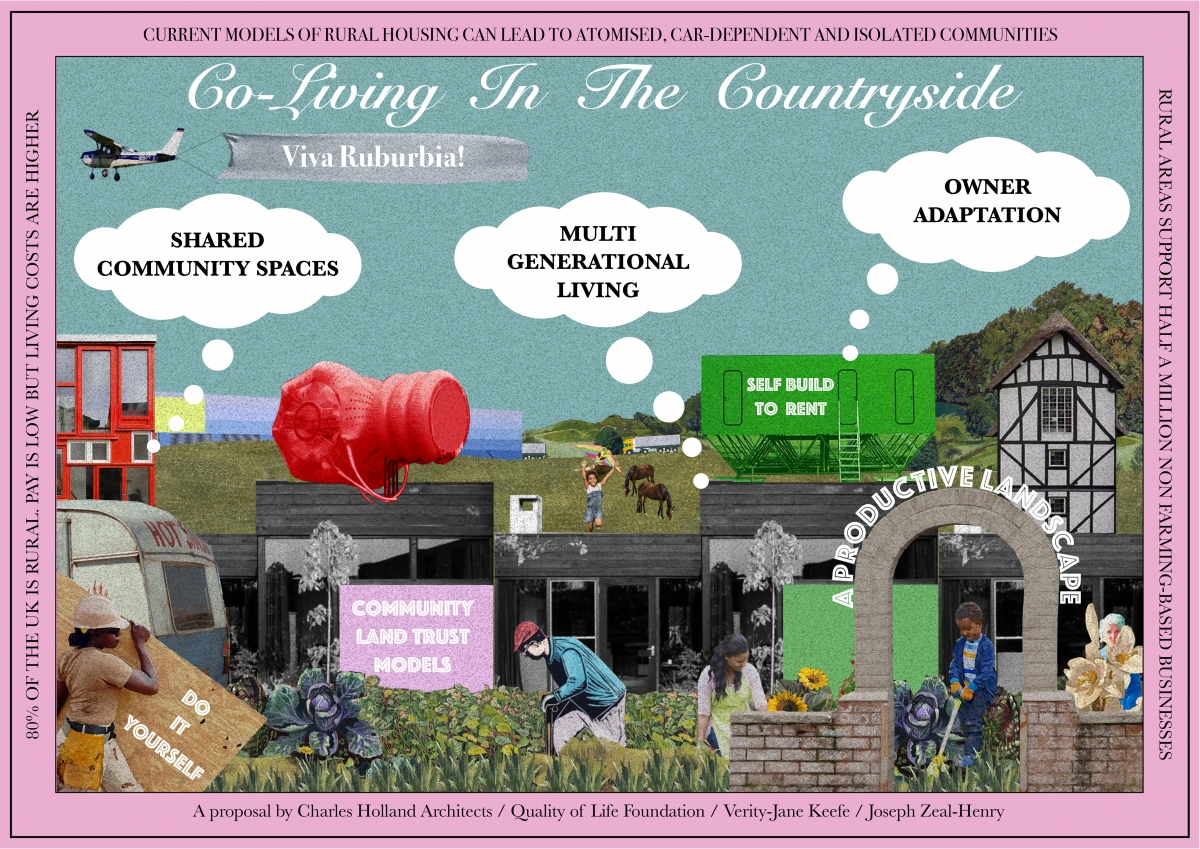

©Charles Holland Architects with Quality of Life Foundation, Verity-Jane Keefe, Joseph Zeal-Henry

Marie Chamillard director, Alan Davidson Foundation × Park Semi

Park Semi (Park): Who did establish the Davidson Prize and for what purpose?

Marie Chamillard (Chamillard): The Davidson Prize is an annual ideas competition recognising transformative design in and around the subject of home. Established in 2020, the prize commemorates Alan Davidson (1960 – 2018)—the architect, artist and technologist who founded pioneering architecture visualisation studio Hayes Davidson in 1989. Alan Davidson was a passionate believer in the power of storytelling, and the prize celebrates traditional and new ways of communicating architectural ideas—from drawing to film and immersive technologies. Each year, entrants are asked to consider a different aspect of future living. Three finalists receive £5,000 to develop their ideas. The overall winner receives a prize of £10,000. Administered by the Alan Davidson Foundation, the prize exists to celebrate innovative design ideas, encourage multidisciplinary collaboration, and promote compelling visual communication. A core ambition of the Davidson Prize is to spark collaborations between architects, designers and disciplines including filmmakers, visualisers, researchers, engineers, and technologists. Each team must include at least one architect registered with ARB (UK) or RIAI (Eire).

Park: The theme of the first annual prize last year was ‘Home/Work – A New Future’, and this year, it is ‘Co-Living – A New Future?’. What kind of process and purpose do you use when you decide a theme? I would like to hear a brief explanation of the theme of the 2022 Davidson Prize.

Chamillard: When going through the process of deciding a theme and developing a brief, we try to find a topic that will resonate with prospective entrants, so that they can draw from their own experiences and find a solution to these challenges—and, of course, come up with an idea that could potentially transform the architecture of the home in the future. For its inaugural year, the theme ‘Home/Work – A New Future’ was prompted by the need to reassess how we want to live post-pandemic. With government-imposed lockdowns forcing many of us to work from home, many people said they would like the opportunity to work from home more often, and the brief asked how the typical home could be adapted for people to work comfortably in the future. This year’s theme, ‘Co-Living – A New Future?’, asked whether co-living could offer a transformative key to the design of our homes, as well as our communities. While some spent lockdowns yearning for a bit of personal space, others found themselves with too much of it. In the aftermath of the pandemic, not only are many experiencing a loneliness epidemic but the UK’s well documented undersupply of housing, generation rent and increasing visible and invisible homelessness are all challenges many of us are facing. Therefore, we were keen to put this question out to the creative community to see what innovative solutions they could come up with to advance the discussion around co-living as a potential design solution.

©Charles Holland Architects with Quality of Life Foundation, Verity-Jane Keefe, Joseph Zeal-Henry

Park: In fact, the architectural topic, ‘Co-Living’ has been discussed for quite a long time with diverse layers and scopes of concept. What is the meaning and definition of co-living in this competition?

Chamillard: Of course, co-living is not a new concept—it already exists in many forms including student accommodation, retirement communities, and multi-generational households. From co-operatives in Catford to self-build in Bristol, and from ‘agrihoods’ in Scotland to third-age collective living in Barnet, experimentation with models for living is nothing new. In 1916 Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant reorganised notions of home, sexuality and gender roles at Charleston Farmhouse. In the 1970s, artist collectives such as Acmefound new ways of exchanging labour for a roof over your head. The cultures of Dutch ‘centraal wonen’ or Danish cohousing have as many similarities with Britain’s historic almshouses as they do with kibbutzim in Israel or Tipi Vally in Wales. Faced with the implications of an ageing population, rising costs of care and the environmental price of energy and embodied carbon, our homes are also increasingly moonlighting as places where people earn a living. On top of that they’re sites of the invisible labour that keeps the supply chains of economies oiled (in the UK alone it’s thought that the value of unpaid work taking place in the homes of today is around £700 billion annually). Are our homes up to the job? The demands being placed on the spaces we live in are perhaps more complex than ever before. There has probably never been a better opportunity for design that rethinks our models of home while transforming lives and safeguarding the environment.

Park: In this context, what did you expect entrants to propose for the competition?

Chamillard: In the prize’s inaugural year, we were very surprised by some of the submissions because teams provided solutions that we had never considered. Before reviewing the 2021 submissions, we had expected that perhaps a retrofit or modularbased solution may end up winning however, it was a technology-based proposal that ended up winning the judges’ hearts. The 2021 winning proposal ‘HomeForest’ was an exemplar of how technology could be used in a positive way, particularly for those who don’t have access to outside space. We felt this scheme would have really resonated with Alan who was an early adopter of all things digital—he loved trialling new things that would blend discreetly into his home and enhance the atmosphere so would have definitely used that tool! So for this year, we threw all expectations on the window as we just can’t guess what the multi-disciplinary teams will come up with when they put their heads together. This year’s diverse entrants proposed creative design approaches for both rural and urban locations and ideas spanned from new ways of embedding supportive social networks in cities and towns to new models of multi-generational living and innovative retrofit solutions. However, a unifying theme across the submissions was one of care—from the care of ageing populations, children and marginalised groups to safeguarding the world’s resources of energy and embodied carbon. Each submission raised great discussions amongst the judges, and it was so fun watching them debate.

Park: Stage 2 finalist teams gave a media presentation of up to 2 minutes. What did you consider about presentation method and media?

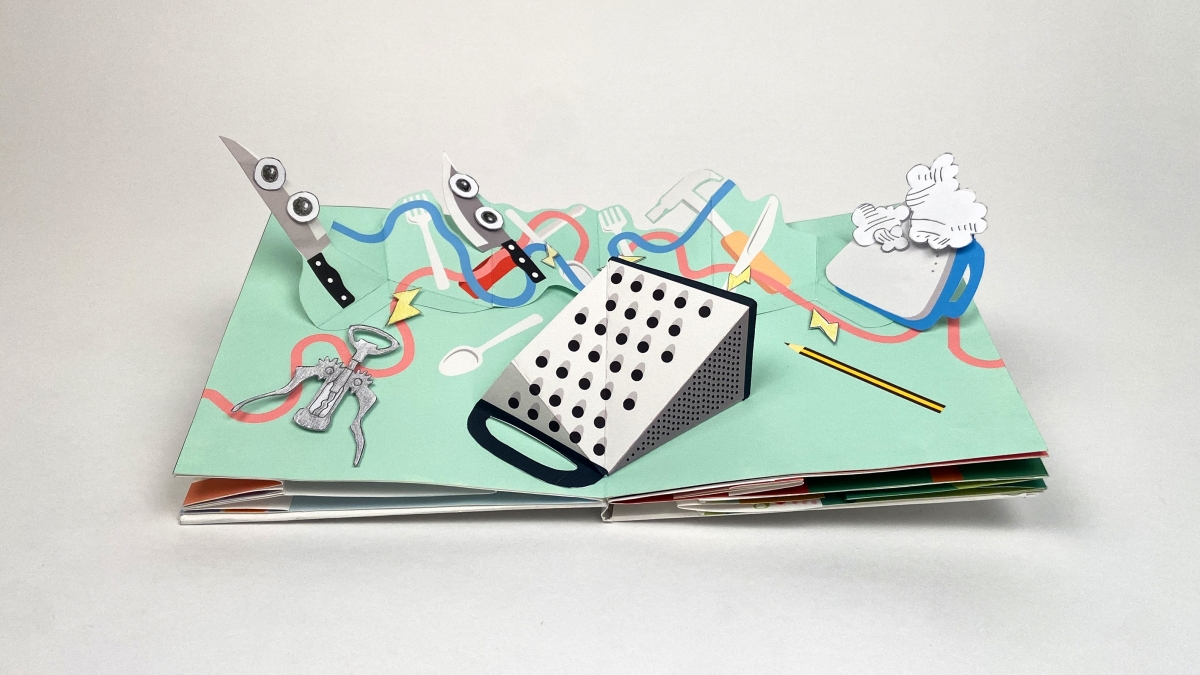

Chamillard: Each of the three finalists are given an honorarium of £5,000 to develop their ideas in which they have to produce a film of up to two minutes as well as three hero shots that best encapsulate what their proposal is all about. The content of the film is up to the finalists and can include drawings, models, film, animation, VR, or any other media they choose to communicate their design ideas in the most effective way.

©Child-Hood (NOOMA Studio)

Park: I would like to hear a brief of three finalists’ works and the basis of their evaluation.

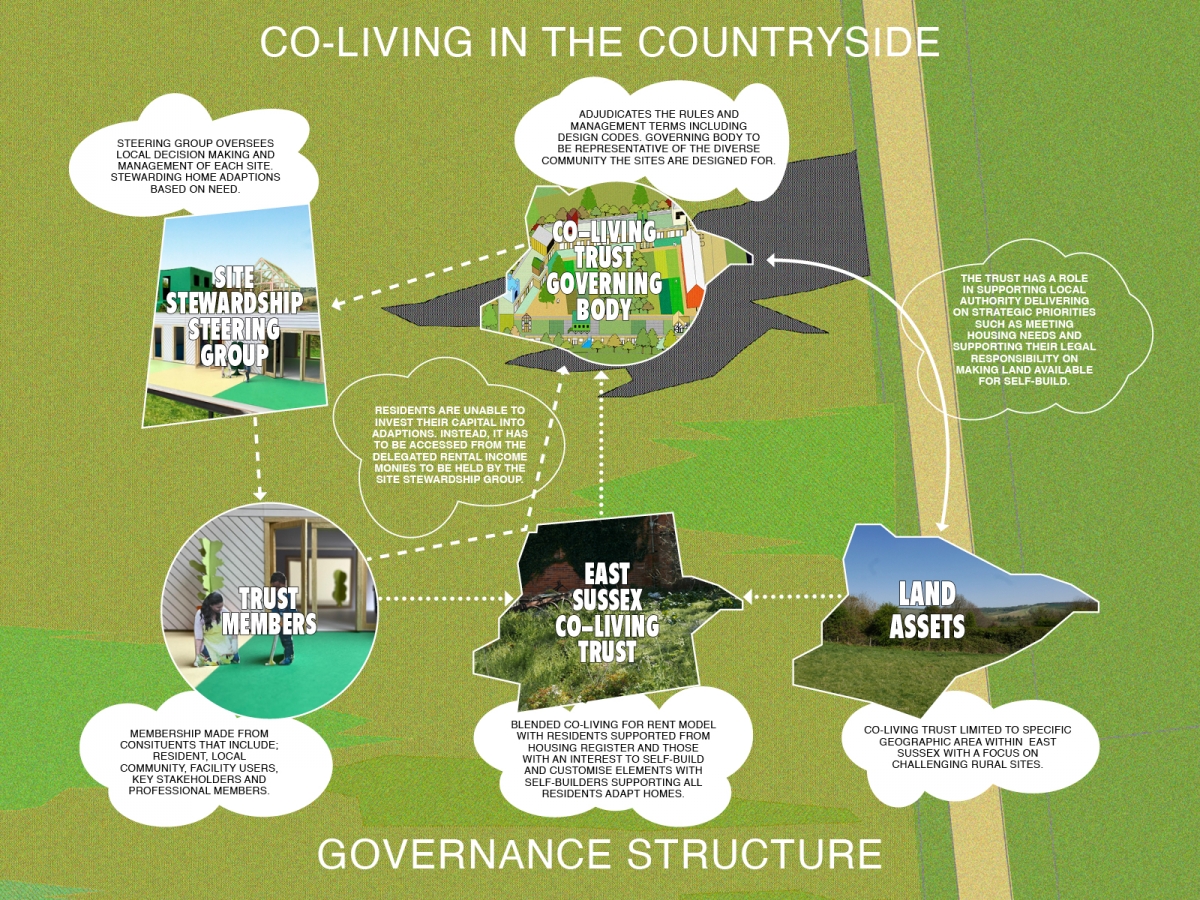

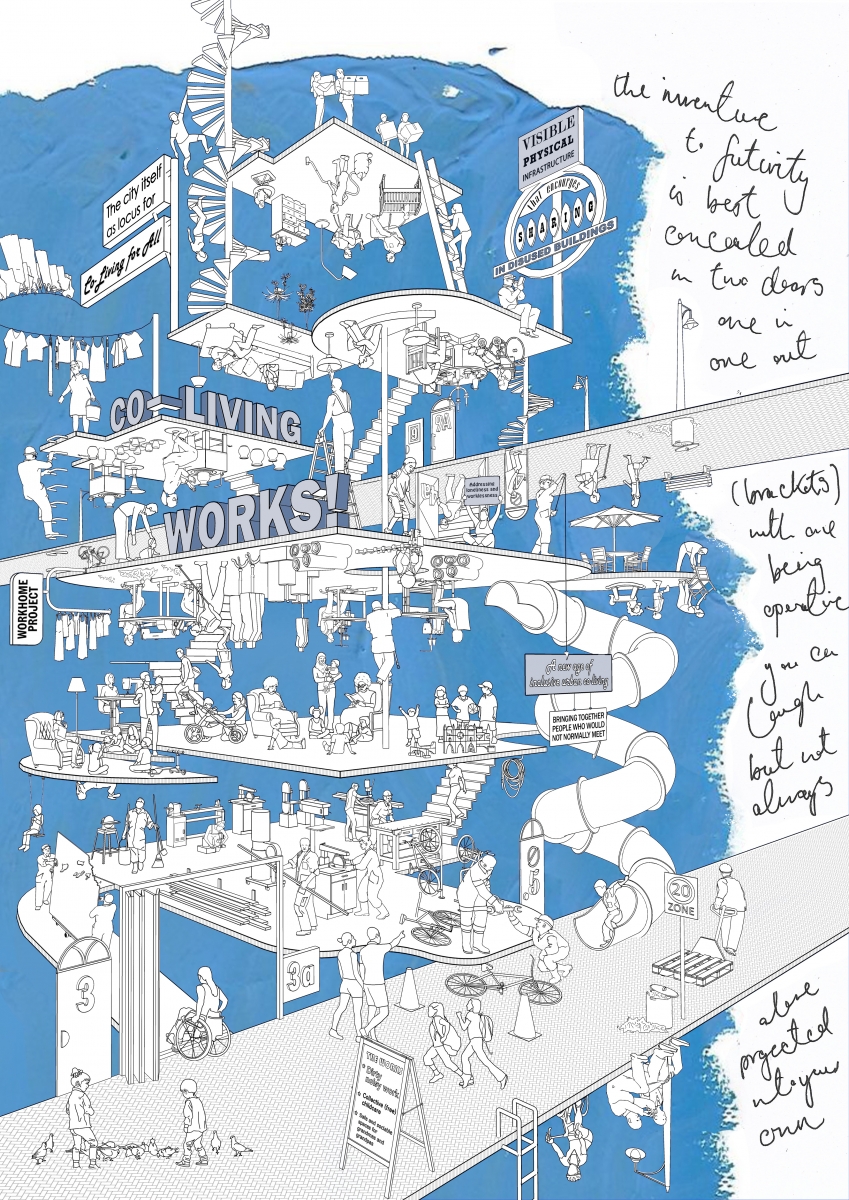

Chamillard: The Winner is ‘Co-Living in the Countryside’ (Charles Holland Architects with Quality of Life Foundation, Verity Sound Advisory-Jane Keefe and Joseph Zeal-Henry). Co-Living in the Countryside is a model for rural co-living. Rural areas in the UK suffer from a shortage of affordable housing and are overly reliant on a narrow development model monopolised by volume housebuilders. The result is atomised communities of singlefamily units in car-dependent cul-de-sacs. Co-Living in the Countryside focuses on a typical site allocated by the South Downs National Park Authority, surrounded by an ageing demographic. The proposal is based on simple timber-framed construction allowing for flexible and variable house types with the potential for shared components such as kitchen/dining, workshop and childcare facilities. Car ownership is reduced through shared transport and on-site workspaces. The scheme combines owner-adaptation, customisation and personal choice with a community-based governance model, allowing for individuals to co-exist while sharing resources, skills and spaces. Conceived as one of a number across East Sussex, the site is owned and run by a community housing association with the input of a steering group and a central board of governors. Individual units are rented with profits recycled through a pool. Improvements, adaptations and maintenance are funded centrally. THE RUNNERS UP is It Takes A Village by Child-Hood (Gankôgui, NOOMA Studio, London Early Years Foundation and Centric Lab). ‘It Takes A Village Child-Hood is childcentred co-living. The old adage says that it takes a village to raise a child. But as cities grow larger, housing denser and connections more digital, the support networks of villagelike communities are being marginalised. Cost and availability of childcare is threatening to tip the balance for families facing high housing costs, rising utility bills, limited space and loneliness. Meanwhile, non-profit childcare providers struggle to find sites in a property market that gives little thought to social infrastructure. Children’s futures are significantly influenced by socioeconomics, quality of early years education and home learning environments. In response, It Takes A Village Child-Hood combines mixed-tenure housing with nursery provision, communal domesticity and family spaces. Taking the form of a toolkit, it addresses design, law, policy and financial viability to achieve an inclusive ecosystem of family-centric communal living options. The typologies flex with family needs and can be adapted for large urban developments or small infill sites, clustering around a communal heart where families learn, play and socialise together. By taking domestic functions out of isolation, the model offers families better quality spaces and more social interaction. ‘Communiversity’ (Moebius Studio with Totem Record, OHMG Video, The Panics, Alex Klein Productions, Armanios Design) is a solution to making co-living happen. Private home ownership is promoted as the ultimate goal in the UK, supported by an abundance of information and incentives. The lack of guidance on co-operative living is a stark contrast. Although successful models of communal living do exist in the UK, 99% of people attempting to form their own commune don’t succeed. Communiversity offers an antidote to the narrative of individualism and private home-ownership, created to equip people with the learning, resources and contacts they need to make their dream of co-living a reality. By pooling expert knowledge and establishing a network of resources, the educational institution and social enterprise helps overcome barriers to communal living. A hybrid of online resources and physical spaces will teach practical and soft skills from a campus of re-purposed office and commercial spaces supported by a global network of communes, co-housing projects and alumni. Academic institutions and government departments are offered unique opportunities to explore successful models for communal living alongside insight on challenges faced. These data sets will help inform and influence policies around co-living.

©Moebius Studio

Park: Co-Living in the Countryside was announced as the winner of the prize. What is the jury’s evaluation of the winner? Also, what does this winning work suggest for 2022?

Chamillard: The jury felt that winning team’s proposal addressed a very real problem that is affordable rental housing in rural locations and they particularly enjoyed how the team combined owneradaptation and customisation with a community-based governance model. The judges felt that this proposal best responded to the judging criteria and could envisage it being rolled out around the UK (and perhaps even beyond!). I think the winning proposal provides an insight into what many people are looking for in a post-pandemic era. Here in the UK, we have seen an exodus from cities and urban centres, as they become increasingly congested and unaffordable, to suburban or rural areas, which offer more space and fresher air. Although housing in rural locations has often been associated with social isolation, particularly for those who aren’t able to get around by car, this proposal provides the perfect solution to combining the outside space with community…and I think we are definitely going to see more developments like this in the future.

Park: I would like to know theme of the 2023 Davidson Prize. If you have a plan, can you tell me? Also, what role do you want this award at the beginning stage to play for architects, architecture world, and the public?

Chamillard: We are yet to finalise the theme for 2023, however the Davidson Prize team is already hard at work, bouncing ideas around and we will announce it to the public later this year. We feel that the prize represents a great opportunity for architect-led teams in the UK and Ireland to showcase their skills as leaders of the increasingly crossdisciplinary teams who hold such great responsibility for the quality of the lives, for the homes – and communities – of our future generations. Therefore, we want this award to ignite a spark in people’s minds—not only in the architecture world, but the general public too. The demands being laced on the spaces we live in are perhaps more complex than ever before so there has probably never been a better opportunity for design that rethinks our models of home.

©The Workhome Project