ʻI am an Architectʼ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

Patchied City, Image courtesy of Midday / ⓒJeong Haewook

interview Oh Yeonjoo, Jeong Haewook co-principals, Midday × Park Jiyoun

The Unreal Real

Park Jiyoun (Park): Both of you completed your industrial design studies in Korea and completed masterʼs degrees in architecture in Germany. Are there any reasons you opted for architecture as your major?

Oh Yeonjoo (Oh): All elements placed within a space. When designing a product, there are cases where the space does not necessarily match the product. To put it simply, I didn’t like it. I thought that we should offer a more integrated approach and to design the space in collaboration with a given product, and so I joined an interior design company. However, the company embarked on a number of building projects. I wondered whether it would be acceptable to construct a building without a degree in such practices, so I decided to study architecture.

Jeong Haewook (Jeong): Design education is typically divided into industrial design and visual design, but in the school where we studied, the faculties were combined, and we were able to take all the classes we wanted to take. I learned that the medium is the means of expressing the subject. For instance, I could take an editorial design class if I wanted an outcome in the form of a book or publication. After familiarising myself with that approach, I thought why not design a building? Consequently, the architecture behind the art of building was a very different realm and posed its own challenges, but I think we had grown used to crossing various media.

Park: While studying in Germany, you created a group named AAPK that introduced and explored architectural discourse related to the virtual technology. I am curious how AAPK was founded.

Oh: The German Städelschule academic courses involved a lot of experimental work. It is a place in which we contemplate how to best establish relationships between new technology and architecture. In terms of technology, I used VR/AR a lot. The term Architecture as Fabulated Reality isn’t rooted to a dictionary definition. After experiencing an image or digital-centred discourse, we arbitrarily added the words ‘virtual’ and ‘architecture’. In the first semester of the school programme on the foundation course, students learn theoretical approaches to the relationship between technology and architecture. I was in a situation in which I had to read a lot of material every week, but no theory was introduced in Korean. The theory is so interesting, so I hope it will be read by many people. AAPK was established as we discussed and translated such materials together. The translated texts are included in the book Architecture as Fabulated Reality published under the name of AAPK. I think readers gain a strong sense for the point where the architecture meets the term fabulated reality. When we were studying in school, concepts like the metaverse were only just beginning to find currency. At this point in time in the architectural field, VR was only seen as a tool through which to preview a space to be built.

Jeong: I think our present period under Coronavirus Diesase-19(COVID-19) has mean that the concept has received more attention. In fact, when you go abroad to study, in most countries, young architects have few opportunities to build buildings – unlike Korea. As a result, everyone does weird things. (laugh) When they return to their own country after an experimental phase at school, it can be difficult to find reasons or the appropriate contexts in which to continue such practices. There is even the suggestion that this is not architecture. However, we harbour the desire to call such experimental or progressive forms of design architecture as well. After all, since it is virtual, it is real even if it is not real, and it can be real even if it is not real.

Park: There have been upsides and downsides in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Architecture as Fabulated Reality was intended as an exhibition catalogue, but the exhibition was not possible due to COVID-19. I am curious about the works that were scheduled to be exhibited, such as Director Jeong’s work Patched City inspired by Rem Koolhaas’ article ʻJunkspaceʼ?

Jeong: In the article, Rem Koolhaas issues a death sentence on modern urban architecture, stating that every space in the contemporary city is nothing more than a collection of rubble. I found Rem Koolhaasʼ cynical attitude a bit annoying. (laugh) I wanted to deal with this concept constructively. I wanted to find something new in form by re-editing and reorganising the uglier parts of the city. The result was a kind of digital landscape, in which I modeled virtually nothing. The byproducts of taking images from 3D scans or Google Maps screenshots and transforming them are the main body of this work.

Installation view of Saturated Space, Image courtesy of Midday / ⓒOh Yeonjoo

Park: Director Oh Yeonjoo’s work Saturated Space was the result of paying attention to the interiority of VR. Could you explain this in detail?

Oh: VR presents a user with a space that completely surrounds and immerses. You can experience a complete interior with no exterior. The work began while thinking about what an individual can do with VR, which has the defining characteristic of interiority, and the first thing that came to mind was a carve-out: the user creates a new space by carving out the space surrounding them on their own terms. I spent most of my time making those tools.

Park: When you play a game, the space expands as the user walks. Is it a similar concept to this?

Oh: Itʼs similar. However, my work does not carve out space naturally when it moves, but I have to hold a tool in my hand and extend my arm. Inside, a person can only carve as much as one can reach with his arm. The shape is drawn from the architectural drawings of the architects.

Jeong: As we proceed, interiority has become one of our interests. Recently, we talked until 2 am in the morning about the kinds of interiority in which we are interested. (laugh) The bottom line was that introspection, like anything else, can be divided into two categories: form and experience. Form refers to the quality that it possesses independently, even if all relations with the outside world are dissected, and experience is formed through a certain relationship with the human body and cognition.

Oh: The two co-exist in my work. By borrowing the morphological characteristics of architectural drawings, we explored the unique formal properties of interiority, and experimented with experiences through the act of a person inside and reaching his or her arms to effectively carve out space.

Data Compiled

Park: Are you currently working on any two projects? What about Upperhouse Up, a research project, and Existing Geometries, a renovation project; one comprised of data and the other of buildings, and so the nature of the two is very different.

Jeong: The studio rolls on no matter what, and I thought that there would no difference in sticking to designing buildings. We wanted to lead the studio in such a way that could be combined with other things we do, and we also wanted to set a new precedent. However, these are difficult times. I have to be inside the data but go to the site to pick up something at the same time, and I think there will be synergy between the two when we approach them in tandem. I think itʼs less convincing when someone who doesnʼt know how to deal with real buildings deals with data or virtual concepts. I want to take both with a long view.

Park: Is Existing Geometry a typical renovation project?

Oh: Yes, that is correct. It was a project in which we renovated a three-story detached house as an office building. There was a client, and we began with the actual measurement. It was a project that focused on bringing out the latent geometric proportions of existing buildings.

Park: I heard that Upperhouse Up is the data-based project of Upperhouse, an apartment building project in which Oh Yeonjoo participated.

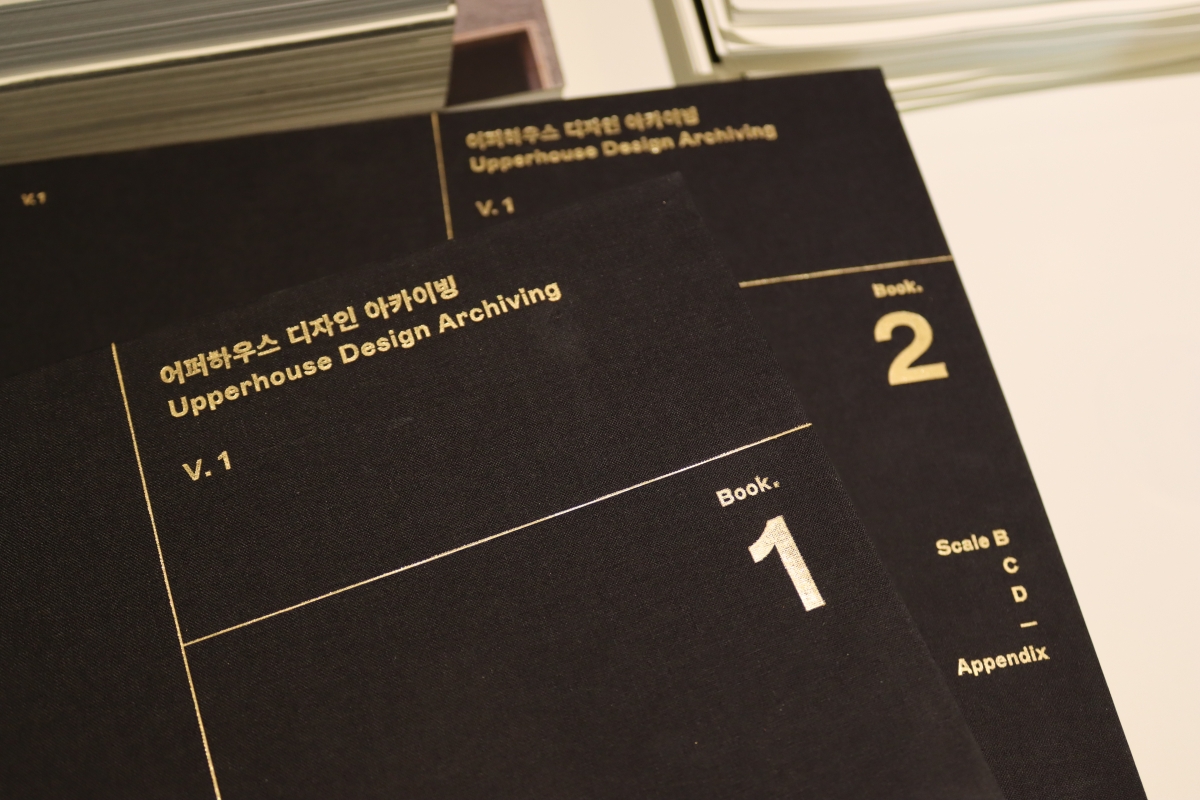

Jeong: Rather than constructing a building right away, I thought I should first read the building and collect its data. During this process, I thought that it would be architecturally meaningful to establish a guiding logic and process the data to find new possibilities. One of the projects in which we participated was Upperhouse, which was a huge, large building. The project process is divided into three stages. Step 1 is to research the concept. It was to organise the architectural language or methodology of the work in a systematic way. Step 2 is the process of deriving a systematic archiving strategy and organising the data accordingly. Step 3 is to publish a book with the ISBN stamp. We are now completing step 2. By dividing the space according to the scale, we are analysing the objects in order from small areas such as kitchens and bathrooms to households and buildings. In addition, we are researching aesthetic approaches and themes separately at all scales. I think it took about nine months to get here.

Through the Lens of Aesthetics

Upperhouse Up

Upperhouse Up's interior collage images, Image courtesy of Midday

Park: It took less time than expected given the large volume of 650 pages, right? (laugh) The collaged image of interior elements was impressive. Is this part of the aesthetic considerations?

Oh: Thatʼs right. A collage is an image that reveals the aesthetic elements of the project on separate terms. It was a collage of objects from walls, floors, and ceilings. One image is powerless, but hundreds of images can capture something in each space.

Jeong: Overall, the goal was to create a resource book for designers. Drawings are not actually a medium for designers, but a tool to persuade builders and clients. Although we used the form of drawings, we set our own standards and reconstructed things such as the combination of information. In the meantime, the aesthetic has separated it out into a separate category. I wanted to communicate the message that beauty is something that can be set out, defined and established separately.

Park: During the interview, I found the two of you to be like one person. I was a little surprised when you said that you had been talking about interiority until 2 am in the morning! (laugh) Are your interests always the same?

Jeong: We are very interested in elements such as form, that is, defining an aesthetic.

Oh: We are together 24 hours a day and tell the same story every day, so our thoughts are hard to distinguish. (laugh) What I am particularly interested in these days is fashion. We tend to pay attention to proportions, physique, and colour arrangement.

Park: Itʼs interesting to look at most things, not just buildings, from an aesthetic perspective.

Jeong: We also like Chung Guyonʼs architecture. However, I am less interested in architecture in a social context, and I am more interested in form and proportion. I also like military plastic models. I am not interested in social contexts or functions at all, and I think that war should not happen, but there is aesthetic pleasure that military plastic models satisfy. In terms of the digital realm, there are less ethical issues pressuring these things. Aesthetic effects are separated from objects that have a suggestive function. So I think Iʼm starting to see it from an aesthetic point of view.

Oh: We focus on visual features and think about how best to maximise those features.

Jeong: I think it will offer a structure through which we can collaborate with people who are good at physical things.

Jeong Haewook (left) and Oh Yeonjoo (right)

Oh Yeonjoo and Jeong Haewook, our interviewees, want to be shared some stories from Lee Seungho (principal, STUDIO Seungho) in May 2022 issue.

the form of their projects. The two majored in industrial design at Seoul National University and undertook masterʼs degrees in architecture at Städelschule, Germany. They are the chief editors of Architecture as Fabulated Reality (2020).