SPACE April 2022 (No. 653)

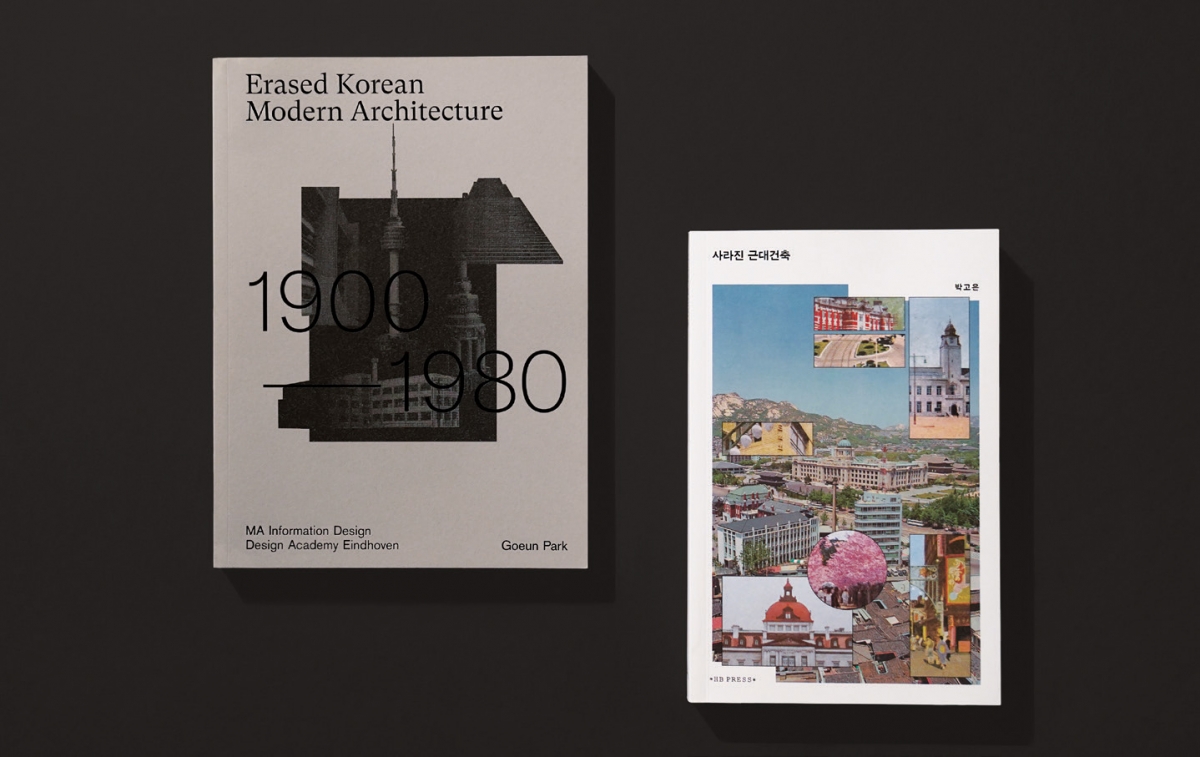

Erased Korean Modern Architecture authored by Park Goeun was published in January 2022, highlighting the erased works of modern architecture in Seoul, Korea, as negative heritage sites. The designer’s log, which documents traces of vanished architecture from the various data archived in movies, newspapers, postcards, news, and so on, cuts across Korea’s modern history in terms of space and architecture when a certain period of time is removed from historical record. In conversation with the author, here we will hear stories of this erased time, which shed light on modern architecture obscured or erased by propaganda such as the liquidation of past history, anti-Japanese sentiment, and erasing traces of military dictatorship.

interview Park Goeun principal, Mercurial × Bang Yukyung

Bang Yukyung (Bang): I am curious about the career background of the author, as the book Erased Korean Modern Architecture focuses on modern architecture through the eyes of a designer. I heard that it was based on a thesis written in the Netherlands while completing your studies. You decided to go abroad to pursue a career in the design industry—what was the trigger?

Park Goeun (Park): I studied visual communication design in college. As I was interested in publishing magazines and books at the time, I worked for hongdesign for about five years after graduation. It was a time when print media culture was in transition from paper-based to digital media, so I naturally developed an interest in digital media, and that is why I started to prepare a study abroad in 2018. Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands teaches graphic design in a non- traditional way. Information design, which I majored in at the academy, can be misleading in that a common misconception is that it teaches you to draw graphs, diagrams, or infographics as this field is not well-established in Korea. For the most part, a master’s degree course allows students to independently select their topics and to visualise collected data following a period of research. The key is how best to present the data through visualisation of a sufficient quantity of intertwined data from the designer’s perspective. The subject of my thesis was on Korean modern architecture, and this book was based on that, with some amendments.

Bang: Personal investigation proceeded in various forms, from a thesis to a website, an exhibition, a book, and so on. What is it in modern architecture that interests you?

Park: It was a trace discovered in a house that incidentally caught my attention. About one year before I left for the Netherlands, I rented a personal studio in Ogin-dong in Seochon, Seoul, in preparation for my studies abroad. Strolling around the neighbourhood, I was met by several strange masonry columns, stone walls, and steps tainted with coloured sprays in the most unexpected corners. It prompted questions such as ‘why are these placed here?’, which led me to the discovery that it is a vestigial trace of the luxurious villa ‘Byeoksusanjang’ built by Pro-Japanese Yoon Deokyoung. The villa was destroyed in a fire in 1966, and completely demolished in 1973 in the name of a road improvement project. I figured that buildings that have stood for a good amount of time and then disappear through the gap between modern architecture and traditional architecture. It was my intention to archive the stories that sit behind the erased time between now and the past through architecture.

Bang: It must have put you in a difficult position to fix the subject of this research, the era, and the architecture?

Park: The Japanese colonial period was first proposed as the focus of attention, but I sensed that the absence of certain works of architecture is not confined to a particular era but to the long march of history which presents discomforting memories to our people. That’s why I extended the period of investigation to the period after 1900. Dutch professors were also interested in our history, which stretched from the Korean War to the years of the military dictatorship. Consequently, this resulted in three different chapters per era in the book.

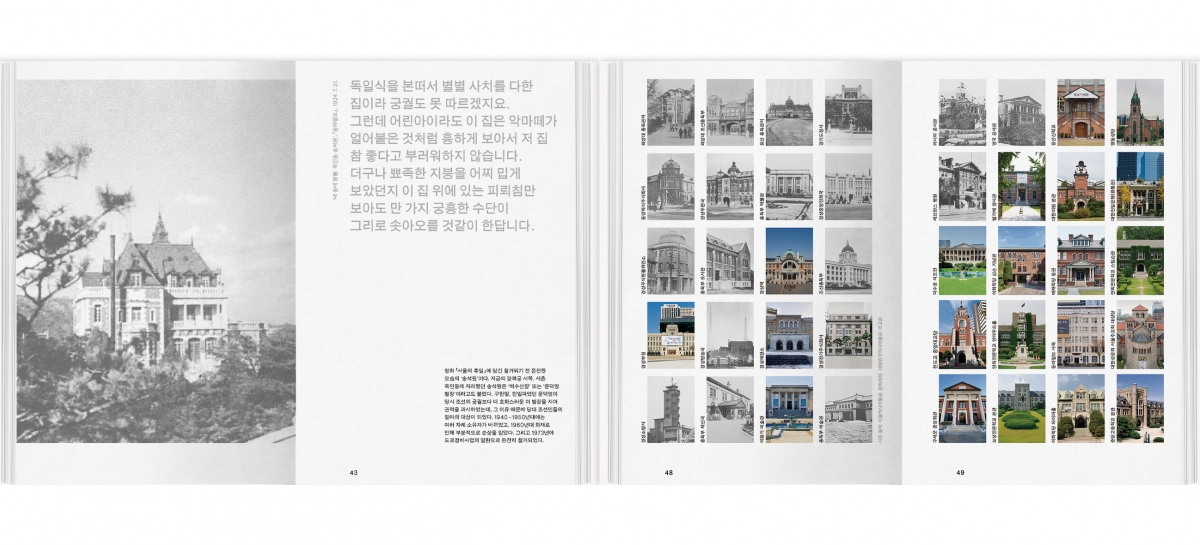

Bang: Each chapter moves in chronological order to reveals the logic that addresses the problems of demolition, such as anti- Japanese sentiment regarding the colonial period, the need to clarify the past, the Korean War, the fortification plan for Seoul, and erasing traces of the military dictatorship. In Chapter 1, there is a table comparing buildings built by the Japanese colonial government and those not built by the Japanese colonial government.

Park: Comparing the buildings that have been demolished because of their historical or colonial heritage to existing ones was intended as a means of revealing whether the notion of negative heritage had become a priority for demolition in the process of urban development. When making the first list, the modern architecture that remains in Seoul as we remember it was listed on one side, and the buildings that were built and demolished in the same era were organised separately. For the data relating to the demolition of modern architecture, I referred to the papers of several researchers, including Ahn Changmo (professor, Kyonggi University). It was interesting to see these results emerge simply by gathering two different groups of buildings together that were built in the same era and setting out the table.

Bang: It is impressive that the professors and students noted that they were both curious and mystified when a documentary video (1995) of the dismantlement of the Government-General of Joseon building was shown on the day the thesis topic was first presented at school. What is their view of negative heritage and how does it differ from ours?

Park: When I was embarking on my thesis, I received guidance from a professor who was a journalist, not a designer. During that time, the professor asked me about ‘anti- Japanese sentiment’. It is a familiar concept to us that buildings from the Japanese colonial era were demolished to obscure a troubling past, but from the perspective of others, I felt for the first time while talking with the professor that this approach may not be reasonable. I wanted to address the reorientation of a point of view throughout the entire book by extending it not only into the colonial period but also towards the Korean War and the military regime.

Bang: What makes it difficult for those in the Netherlands to understand anti-Japanese sentiment, given that they suffered the Holocaust?

Park: Although the Netherlands experienced the Holocaust during World War II, they were a colonial power before then. The reason why they feel that Koreans anti-Japanese sentiment is particularly unusual might because of the friendly relationship between Indonesia and the Netherlands, previously hostile countries, in comparison to Korea- Japan relation. It may also be attributed to the fact that Europeans are unfamiliar with what Japan did was similar to what the Nazi had done. In the case of Taiwan, which was another Japanese colony, the government- general building still remains, and the relationship is different from our own. As the Netherlands is a country that values practicality, they were more curious as to why they were trying to destroy a sturdy stone building that in its historical value and whether it could still be used today in Korea.

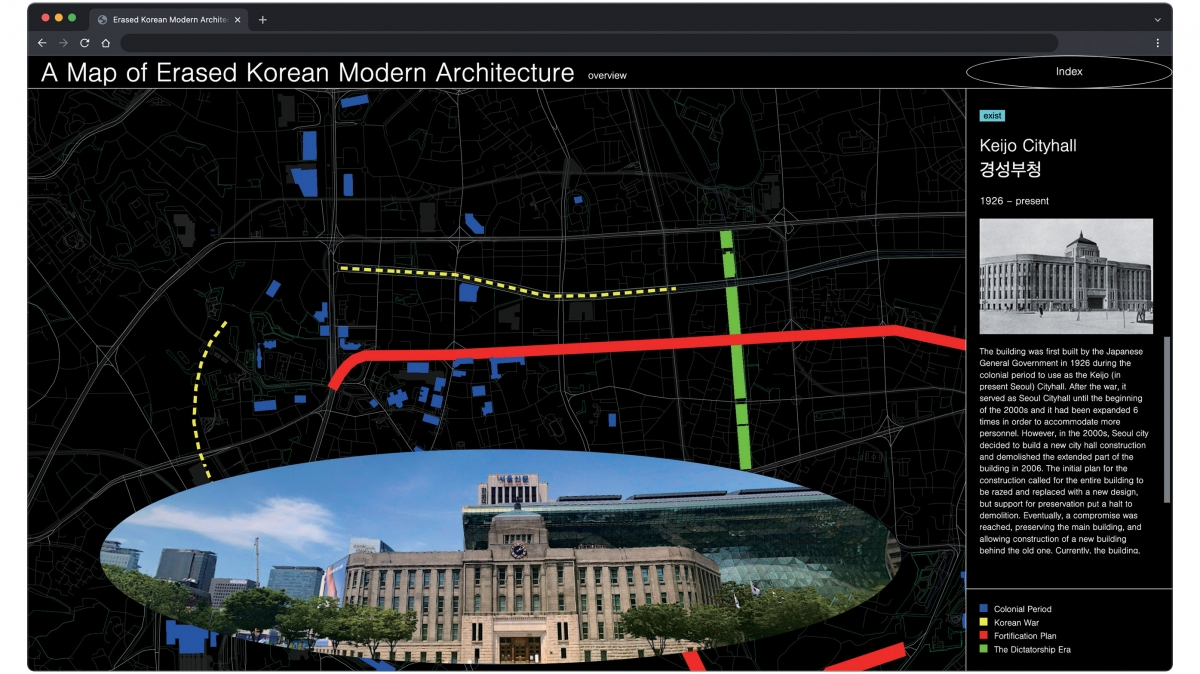

Bang: The master’s thesis was published across two media: book and website. Buildings were classified according to keywords by directly building a website, and a map was also produced across which you can view articles related to demolition, recorded videos, and the current conditions of structures. I felt that drawing a ‘topographical map of perception’ on an actual map would be different

from the approaches taken by previous studies that dealt with similar subjects.

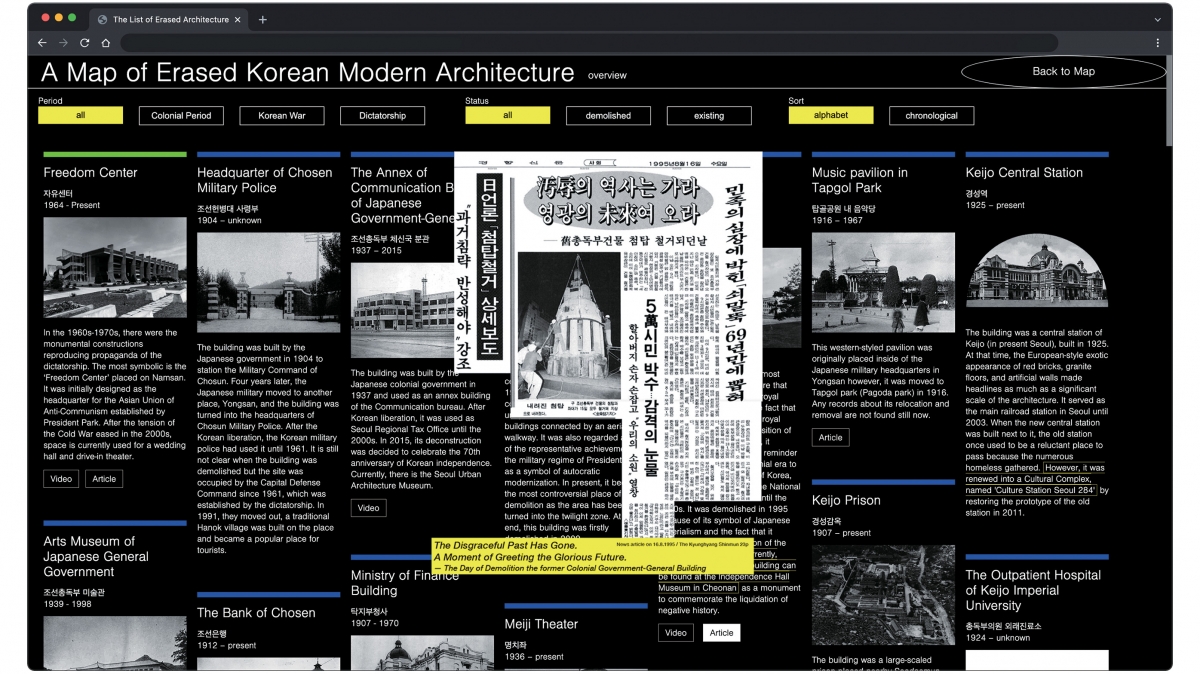

Park: It was a challenge to conduct one research project across two media platforms, particularly in terms of design. The book and website are based on the same information, but in books, research subjects are arranged linearly according to time, whereas on the web, users can choose what they want to see and cross past and present information, independent of the historical context. I wanted to make it an interactive map-based on ‘information storage’. Therefore, it was an important task to be able to map and visualise building information across different time zones on a map and to feature information about the contemporary physical location. The website made it possible to categorise buildings by era, whether or not to demolish them, and organised them by function. Related newspaper articles and videos were also archived here. In addition, the debris left behind after demolition and historical landmarks built on the same site were collated and arranged in a single register. I put a lot of effort into building the website, but I haven’t been able to translate the English into Korean because I haven’t had the guts to complete it yet. (laughs) In this book, I mitigated my disappointment by printing a map that shows the location of the building on the inside of the back cover.

Bang: It must have been quite a burden to translate the thesis and publish it in Korea. Unlike the thesis, which begins with photographs of Seoul in 1927 and 2000, respectively, the book begins with over 20 pages of stills from Korean black- and-white films in Seoul in the 1950s and 1970s. Although it is the same print medium, I wonder what changes were made between the thesis and the book.

Park: It wasn’t like that when I was writing a thesis abroad, but when I decided to publish a book in Korea, the first thing I was worried about was the opinions of domestic experts and researchers. As a designer, I have archived works of modern architecture as the subject of my thesis, that is, as an object of data collection, in the context of ‘data visualisation’. Since the thesis mainly deals with broad frameworks related to history, it is not possible to include detailed stories about individual buildings. So, I tried to supplement many moments with the information and images that were lacking in the book. At the beginning of the book, there are stills from movies archived during the preparation of the thesis. It was a way to observe how modern architecture had been reflected in the eyes of people at the time. At the end of Chapter 1, forty-five photo postcards from the Japanese colonial period buildings are listed, and detailed explanations about the completion, transformation, and demolition of each building have been added. In particular, the story of the Bando Hotel, a commercial facility, was added to Chapter 1 in order to examine modern architecture by use, such as government offices, commercial facilities, and religious facilities. Chapter 2 deals with the statue of a great man and an underpass that suddenly appeared in Seoul after the Korean War, and in Chapter 3, the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, which is currently used as the Korea National University of Arts, is a new concern. I was also in charge of designing the book myself, and while archiving documentary photos taken in public, I selected the examples that were of greatest interest according to the designer’s point of view of the municipal photos and decided on the bolder aspects of the layout. I also included photos taken when I returned to Korea and undertook a field trip.

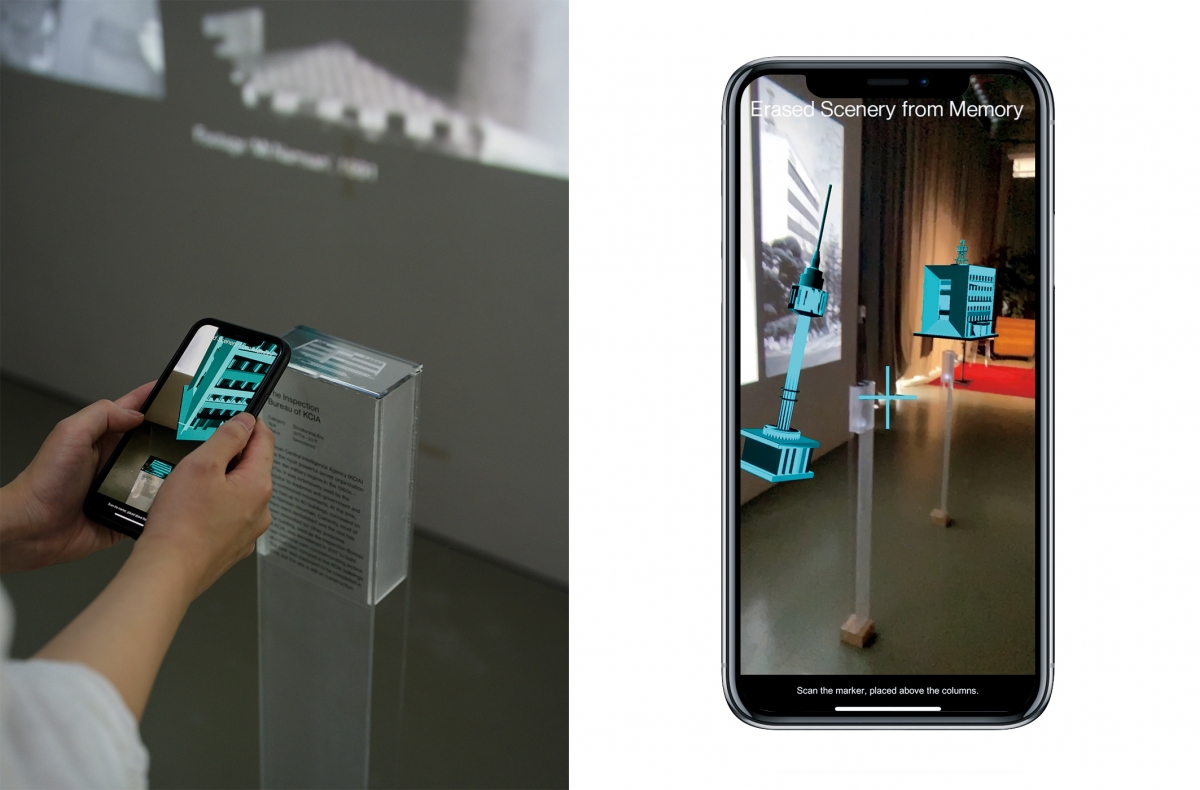

Bang: I saw the master’s course graduation exhibition, which was presented based on this research, on your website. The part that allows you to see the missing buildings through augmented reality (AR) is particularly impressive. How was this made possible?

Park: While preparing for the graduation exhibition, I wanted to restore the missing building through an invisible layer of AR. I thought that the concept of a layer that could be accessed through a device, a layer that exists but does not exist, would fit with the characteristics of the buildings I have archived. I developed an application that would allow you to see fragments of modern architecture restored in 3D by scanning the installation in front of the image projected on the wall of the exhibition hall. It was restored in 3D with reference to old photos and drawings. If the scale of the exhibition could be increased, I intend to reproduce the old streetscape where buildings have been restored through AR at the site where the actual building has disappeared.

Bang: In the book, you expressed the hope that the layers of the city that have accumulated over time would present a rich and dense urban life. Those expressed on paper, on the website, and in the exhibition were also read as ways of recording and the memories possessed by an individual. What is the method of preservation or remembrance we should pursue to preserve the stories that lie deep within a building and which will one day disappear?

Park: Although perceptions of modern architecture have changed gradually since the 2000s, modern heritage sites such as the buildings of the Central Intelligence Agency at the foot of the Namsan Mountain and the Seoul Animation Center, the former KBS broadcasting station, have disappeared in the last five-to-six years. The Annexe of Communication Bureau of the Government-General of Joseon building, which used to be the site of the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture, was also demolished in 2015 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the liberation and so to erase traces of colonial rule. Although it was not revealed in the book, I guess that the logic of real estate and capital is working with stealth under the superficial reason of removing signs of the traumas of the past. According to the logic of the market, it is important to keep good records of buildings that disappear before the possibility of preservation. The reference provided by a master’s thesis advisor may be one way. Rotterdam, the Netherlands, was one of the most heavily damaged cities in the World War II. The entire city was burnt down in the bombing of 1940, and 70 years later, in the city that was rebuilt in a completely modern form, the boundary of the old city centre that had been lost in a historic fire was installed on the street to commemorate the extent of the old city. The design project ‘Brandgrens: Rotterdam War Memorial of WWII’ was also undertaken. We often place signposts with dry explanatory texts engraved on them in inconspicuous locations. I think there are various ways of capturing the attention of members of society while documenting the history and works of architecture

that have vanished from the city.

Bang: I’m wondering about your next step. Is there another book in the works?

Park: Through this study, interest in the ‘vanished or soon to vanish’ has grown. As a visual designer, the point of restoring and visualising the vanished and the invisible is interesting. If given the opportunity to publish another book, I would like to collaborate with architectural researchers to feature a range of voices and professional opinions concerning modern architecture. At that time, I think I will be able to show work more focused on data visualisation from the designer’s point of view. Personally, I entered the Ph.D programme at the Graduate School of Design this year. When I have the physical time to expand and continue connected research, I will try to translate the website into Korean and to open this as a resource.