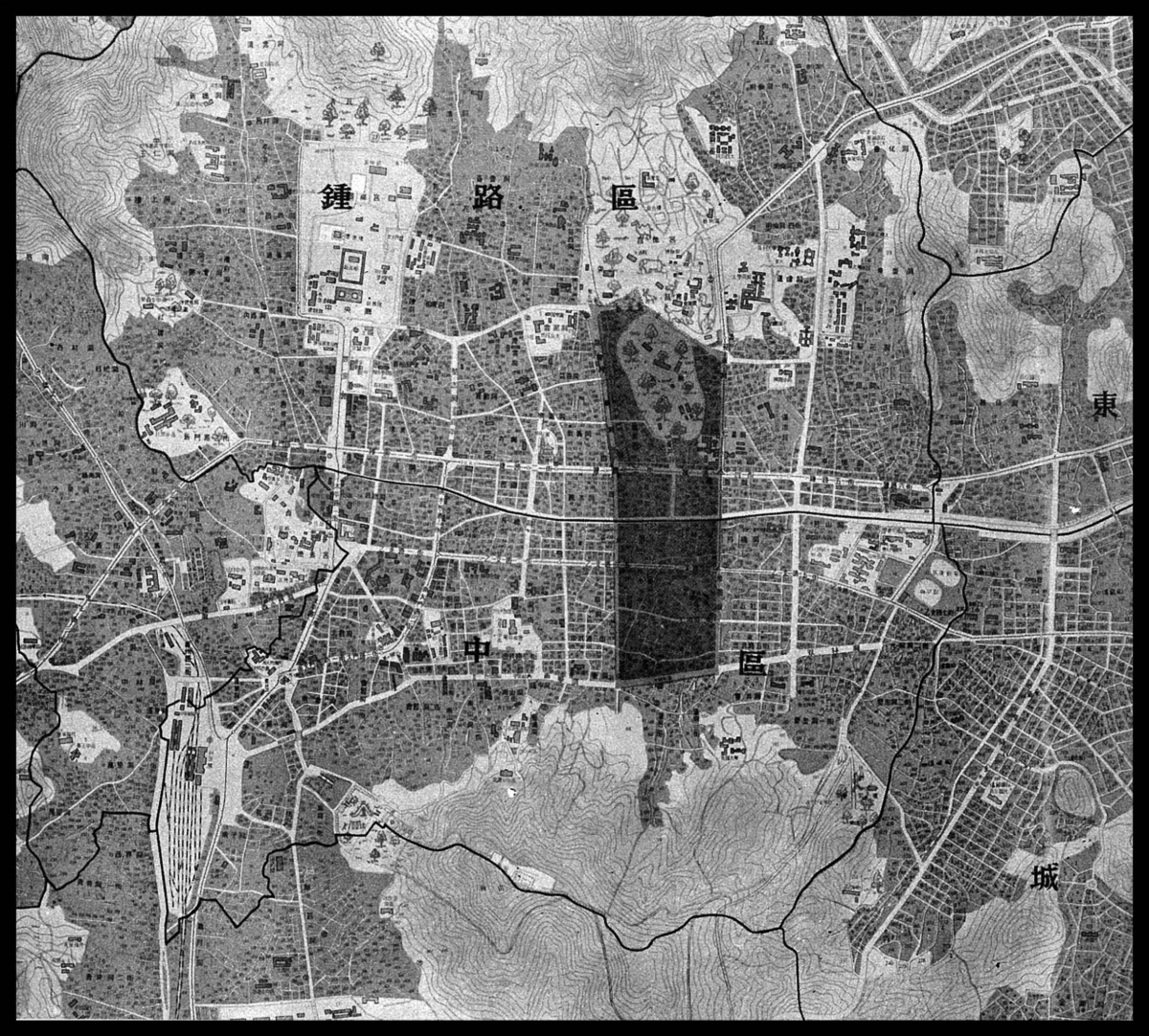

The cover of SPACE No. 11 (Sep. 1967)

In 1967, when the world was in the thrall of the psychedelic sound of the Beatlesʼ ‘Sgt. Pepperʼs Lonely Hearts Club Band’, Seoul was enchanted with the noise of heavy equipment and digging work (and it took a decade before ‘Sgt. Pepperʼs Lonely Hearts Club Band’ was released as an Oasis-licensed album). In the 6th presidential election on the 3rd of May 1967, Park Chunghee was elected after commanding over half of the votes, and the Second Five-year Economic Development Plan began with the goal of modernising industrial structures and establishing a self-supporting economy. As if responding to this, SPACE No. 11 (Sep. 1967) published a special feature ‘Urban Planning’. It was unusual when viewed alongside previous issues of SPACE, which had focused on individual architects and specific building typologies since its establishment. In the same year, special features on ‘Park Kilyongʼs Memorialʼ was published in April; ‘Major designs subscribed to the Competition for Unified Government Buildingʼ in May; ʻCulture Centersʼ in June; ‘Contemporary Architecture in Japan’ in July, and on ‘Le Corbusierʼ in August. Urban planning, as opposed to architectural projects produced by urban planning, was not the primary concern of architecture magazines. This is not that different with the 1970s and 1980s also in view.

The first page of special feature ‘Seoul·1967’, SPACE No. 11, p. 5.

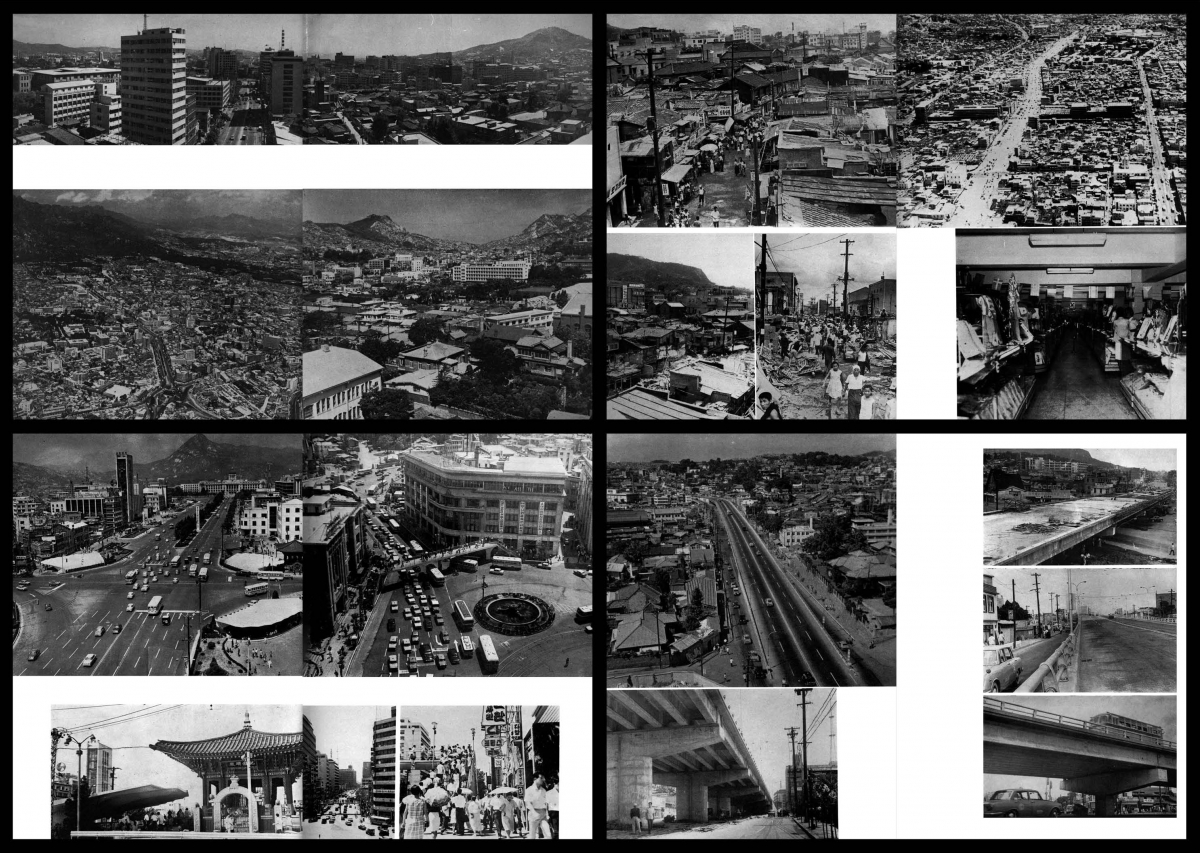

The special feature begins with a group of photos under the title ‘Seoul·1967’. The report covered various features of Seoul, including Sejongno, Seoul City Hall, Myeong-dong, Euljiro, high-rise buildings such as the Civic Center and Chohung Bank, construction sites covered with scaffolding, the UNESCO Building curtain wall, the Oyang Building façade, the Tower Hotel, its chaotic shanty town as good as a construction site or modern ruins, the pedestrian overpass in front of the Shinsegae Department Store filled with white-robed citizens, the overpasses under construction or completed, the Samilro and Yanghwa Bridge before and after the construction, the poor hillside village in Malli-dong, the hanok cluster area, and the Hongeun-dong National Housing Complex. The photographs are colourful, not only in terms of their subjects but also their technique. Aerial photos of Seoul taken in a time when helicopters were not easily available, viewpoints emphasising the height of buildings, snapshots captured from pedestrian eye level, reportage lenses focused on the urban environment rather than buildings as their main subject, contrasting layouts before and after construction, rich gradations and deep depth of field; these photos offer sensuous insights into how Seoul was changing in 1967 rather than offering an explanation. This may explain why the photos have no captions or credits. No information about the photographers or the locations is provided. Readers of the time would have easily recognised the locations. The photos conveyed an imprerssion of a Seoul that was changing and invited further change.

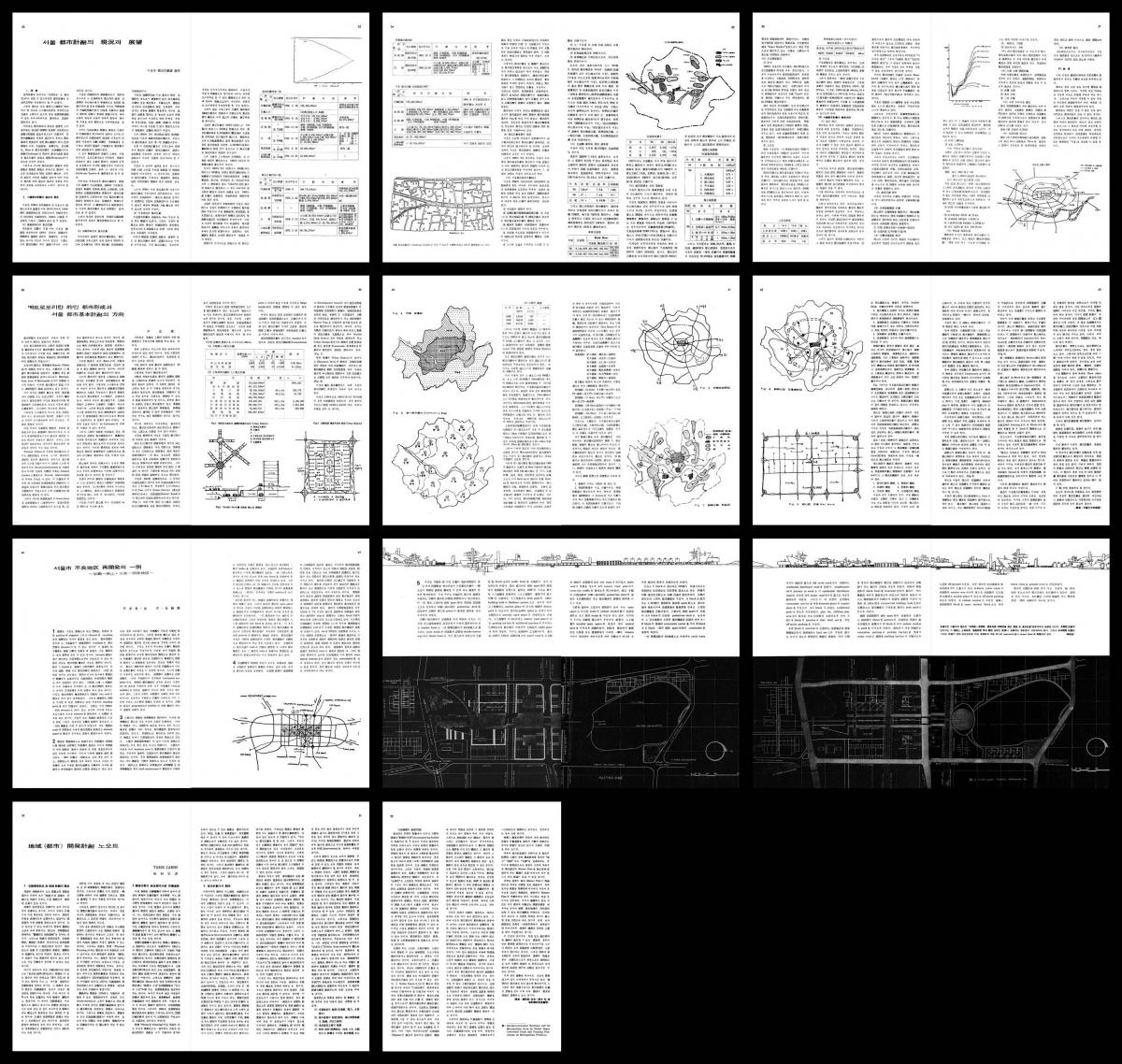

SPACE No. 11, pp. 6 ‒ 7, 16 ‒ 21.

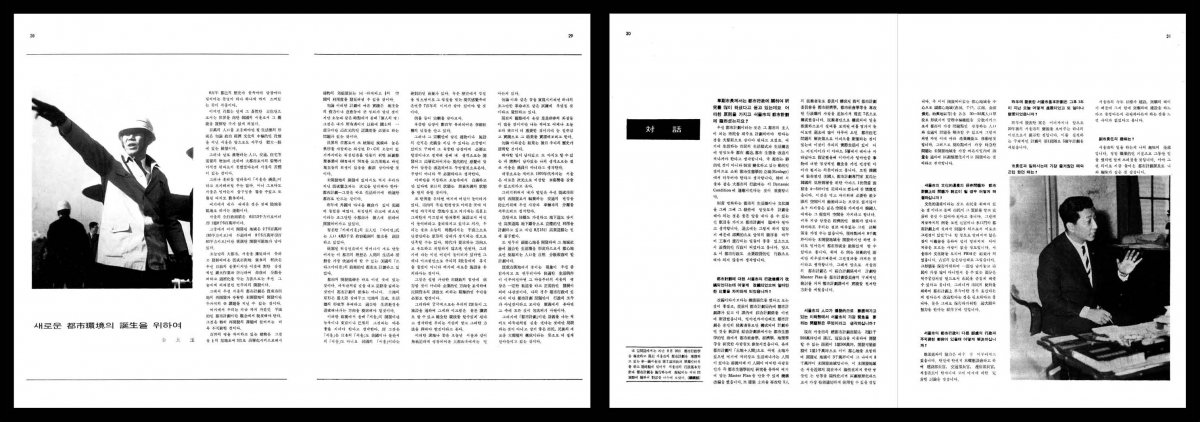

A photo of the then Seoul mayor Kim Hyunok, who raised his right arm upwards at the site, is depicted wearing a hard hat and working clothes. This iconic image, which points to a future through the prism of the construction site, from Park Junghee, Kim Jongpil, Jang Dongwoon, to Kim Hyunok, was a representative propaganda image of the 3rd Republic. He is depicted here as a leader spearheading the myth of economic development, and a collection of these photos was enough for an exhibition. Along with the photo, Kim Hyunok published the declarative article titled ʻFor the Birth of a New Urban Environment’. It may be the first and last time that the mayor of Seoul personally contributed to an architecture magazine, except when giving an interview. Lee Hochulʼs novel, Seoul is Full, was published a year ago, in which there was a sentence that encapsulates the situation in Seoul at that time. Kim Hyunok objected to this. ‘Many people say that Seoul is full, but we cannot give it up. We can open a windpipe in Seoul when we want, and there are many opportunities for it’.▼1 The mayor, who had worked as a transport officer and used to liken urban development to a situation of war, appointed the ‘redevelopment of existing urban areas’ and ‘greenfield sites’ as his targets for his assault. The expansion of Seoulʼs horizons and incorporation of surrounding greenfield sites into urban area through land readjustment was a policy that had been used since the Japanese colonial period. A new method proposed in 1967 was the redevelopment of the existing urban area, that is, downtown redevelopment, and high-rise buildings and three-dimensional development were proposed as the main direction for Seoul. The emphasis was placed on three-dimensional development: ‘I think the first thing I have to do is to redevelop the old urban area, and I will hasten to separate pedestrian and vehicles to prevent soaring traffic congestion’.▼2 Pedestrian overpasses, underpasses, and overpasses were the symbol for a developing city before high-rise buildings were built.▼3 And in the Sewoon Plaza, completed two months later, the separation of cars through an elevated pedestrian deck were a visual demonstration of the vertical expansion of the city's surfaces. The division of pedestrians from cars was one of the main goals of the Housing, Urban and Regional Planning Institute (HURPI) under the Ministry of Construction’s Urban Planning Division, which was established with the support of Asia Foundation in 1965.▼4 The three-dimensional construction of the roads was more effective in terms of symbolic and practical effects than high-rise housing, which was hard to accept due to practicalities and a certain emotional attachment.

The ‘Interview’ with vice-mayor Cha Ilsuck, the following article, revealed a subtle difference in position to Kim Hyunok. Cha Ilsuck, who majored in urban administration, was in charge of urban planning in Seoul at the time. He suggested that ‘administrative’ staff members who majored in urban economics and urban sociology should be added to the City Planning Committee which established the basic plan of Seoul. As the existing committee was made up of only ‘engineers’ who majored in architecture and civil engineering, he argued that this had resulted in a concentration on building apartments. He noted, ‘If a child is born and raised on the fifth floor of this apartment, it is questionable how this child will become a healthy child with a normal conception of things’. Although the six-storey Mapo apartments, which were constructed through a coup dʼetat like a blitzkrieg despite opposition from the United States, were advertised as one of the military regimeʼs greatest achievements, concerns about high-rise apartments were great. This is not unrelated to the fact that most of apartments in Seoul, including Jeong-dong, Ihwa-dong, Dongdaemun, Hongje-dong, and Jeongneung, were being constructed as low-income housing. According to Park Cheolsoo, the ‘policies to solve population concentration in Seoul and the serious housing shortage gave priority to the efficient use of land and supply of affordable housing, and securing livability was set aside’.▼5 The poor conditions of apartments at the time is implied when the vice-mayor of Seoul expressed doubts about whether they would be an appropriate house for a child. Two years later, Wawoo Citizen Apartments, located in Mapo-gu, collapsed four months after completion, causing dozens of casualties and Kim Hyunokʼs resignation. This was another version of Cha Ilsuck’s concerns. The vice-mayor, who was an administrative official, considered that the most urgent task at this point ‘to carry out city planning and develop green areas as soon as possible through better surveying’. He took a different approach to politicians who needed proof of significant achievements over a short period of time.

After delivering the voices of the mayor and vice-mayor of Seoul, the special feature presented ‘Seoul City Planning: Today and Tomorrow’ by the Urban Planning Department of Seoul and ‘The Metropolitan Urban Development and Master Plan of Seoul City’ by Yoon Chungsup of Seoul National University. Both articles, which seem to have copied detailed statistical data and Seoul urban planning, are not suitable for publication in architecture magazines. This was followed by Yoon Seungjoong, Yoo Kerl, and Kim Seok Chul’s ‘The Redevelopment of Bad Districts in Seoul: From Jongmyo to Namsan, 3-ga to 4-ga Districts’. This article is a part of The Survey and Basic Plan for Redevelopment of Wonnamro ‒ Toegyero, Yeongcheon District, submitted to Seoul in January of the same year under the name of Kim Swoo Geun Urban Architecture Research Lab. It was a report that included redevelopment plan of both sides of Sewoon Plaza under construction, in the area from Jongmyo to Namsan, and Yeongcheondong, Seodaemun-gu, which was a densely populated shanty town area. The list of authors in charge of the report included not only Yoon Seungjoong, Yoo Kerl, and Kim Seok Chul, but also Park Seonggyu, Kang Taeseok, Jeon Sangbaek, Lee Changnam, Jeong Changsu, and Kim Boguk. The block around Sewoon Plaza, where redevelopment issue are still contested, already had a redevelopment plan in 1966 when the Sewoon Plaza was under construction. It was a huge block stretching from Jongmyo to the north, Namsan to the south, Jongno-Euljiro 3-ga to the west, and Jongno-Euljiro 4-ga to the east. Aware of this plan, Kim Hyunok implied in the previous article that the wall around Jongmyo could be broken down.

The last section of the special feature was Tarik Carim’s ‘The Implications of Physical Regional Planning’. Karim worked as an advisor to HURPI. Two years later, in 1969, the Korean government and the UN commissioned the 10-year plan for comprehensive national development to OTAM-METRA, a French technology service company, and he was the UN officer in charge of the project.▼6 The article was general, on the concept and planning process. It was a Western expert’s introduction to systematic urban planning, from survey and research to implementation and construction, addressed to politicians and planners in Korea who had little comprehension of these phases.

SPACE No. 11, pp. 32 ‒ 52.

The special feature on urban planning in SPACE (Sep. 1967) consisted of articles written by government officials and civil servants. It included familiar names such as Yoon Seungjoong, Yoo Kerl, and Kim Seok Chul, but they also forged a relationship with the state-run Korea Engineering Consultants Corperation at that time. This special feature testifies to a time when the human networks of SPACE, City Planning Committee of Seoul Metropolitan Government, HURPI of Ministry of Construction, and Korea Engineering Consultants Corp were all intermingled. Researchers who trace the antagonistic relationship between them and study the branching processes of architecture, urban planning, and journalism have no choice but to refer to this article from time to time. We donʼt know yet everything about this tangled relationship. (written by Park Junghyun / edited by Kim Jeoungeun)

In our next issue Park Junghyun will cover ʻKimm Jong-soung and the Evolution of Modernismʼ, which featured in SPACE No. 216 (June 1985).

-

1 Kim Hyunok, ‘For the Birth `1234of a New Urban Environment’, SPACE, No. 11 (Sep. 1967), p. 28.

2 Ibid, p. 29.

3 Jang Okyeon, ‘Mayor Kim Hyunok and His Municipal Administration 1: 1966~1967’, Assault Construction! Seoul of Mayor Kim Hyunok I, 1966~1967, Seoul: Seoul Museum of History, 2012, p. 270.

4 For more on HURPI and Oswald Nagler, who led the organiszation, refer to Lee Hyunjei’s Master’s Thesis, Critical Design Approach and the Emergence of South Korean Urban Design in the 1960s : an analysis on the working methods of the housing, urban and regional planning institute (HURPI), Seoul National University, 2018.

5 Park Cheolsoo, Genes of Korean Houing 2, MATI, 2021, p. 347.

6 The 50-year history compilation committee of the Korea Planning Association, 50 Years of the Korea Planning Association, Korea Planning Association, 2009, p. 169.