Chebu-dong Community Cultural Center ©Namgoong Sun (covered in SPACE No. 605)

The Preservation and Use of Architectural Asset

As members of society, we live embedded within our historical and cultural heritage. As we pass through a period centred on urban development, we became increasingly aware of the importance of structures with historical value neglected so far, and we realised how rapidly these structures are disappearing from our landscapes. The Yongjaegwan (1957) in Yonsei University, designed by Kim Jaecheol, one of the first architects in Korea, was demolished in January 2013; and in 2015, the 100-year-old Science Hall at Paiwha Girls High School was embroiled in a controversy over its demolition. Structures of such profound historical value cannot be restored once they are erased or lost. Today, it is our duty as members of society and community, and for our shared future, to protect those foremost works of rich historical and cultural heritage.

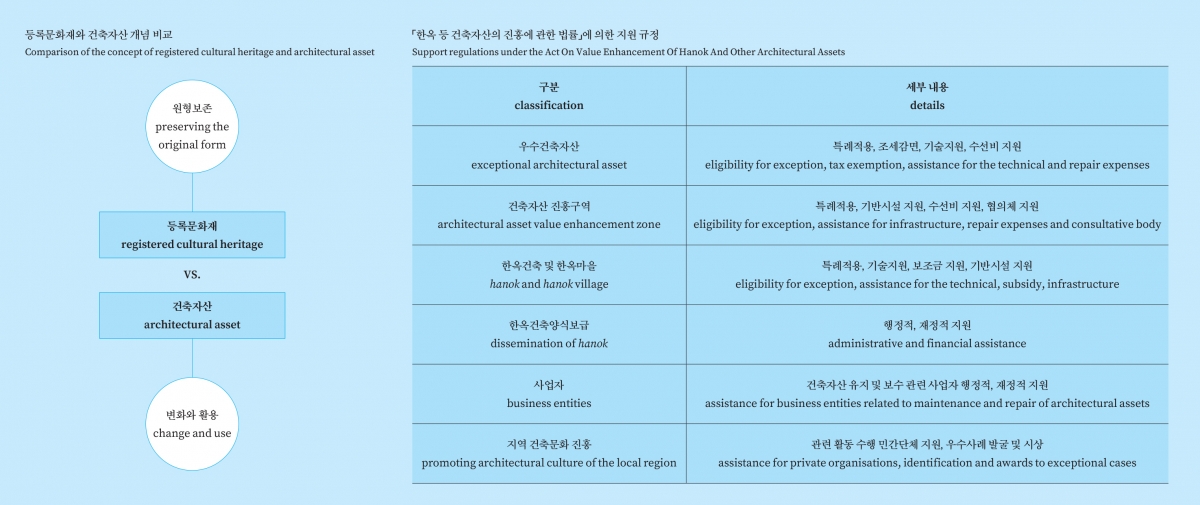

Since the 2000s, the number of cases of buildings that creatively recycle old architectural assets local to their region, such as the hanok (in Seoul and Jeonju), as points of interest for the tourist industry and as bases for broader cultural revitalisation in the region have increased. Accordingly, as voices were raised over buildings and spatial environments that should be recognised as cultural heritage, preserved and actively used, the Act on Value Enhancement Of Hanok And Other Architectural Assets (hereinafter Act On Architectural Assets) was ratified. The Act aimed to promote systematic policies in support of hanok and to prevent the indiscriminate use and loss of modern architectural assets. The term ‘architectural asset’ gestures at buildings, spatial environments, and infrastructure with social, economic or scenic value sustainable from the present to the future, which either has significant and unique historical or cultural value, such as hanok, or contributes to promoting the architectural culture of the State or the formation of the identity of any local region (Article 2).

Until now, the only framework for legally preserving modern and contemporary buildings was the Cultural Heritage Protection Act revised in 2001, the system of registered cultural heritage.▼1 The present terms target buildings that are over 50 years old, whereas architectural assets do not place any restrictions on the construction period so they include modern and contemporary architecture as long as those proposed structures have meaning and value for the local community.▼2 In the way that the term ‘asset’ is used instead of ‘heritage’ or ‘resource’,▼3 one must bear in mind that it is a proactive concept that seeks to actively operate while also preserve valuable elements rather than the original form.

The Act stipulates that the state should formulate ‘Master Plans for Value Enhancement of Architectural Assets’, and local governments should establish an annual Implementation Plan for the Value Enhancement of Architectural Assets every five years to systematically promote related policies. Since the number of architectural assets is vast when an introductory survey is conducted, a national-level specialist institution is required to implement policies effectively. However, at present only the ‘Architecture & Urban Research Institute National Hanok Center’ has been installed, which is limited to reflecting upon hanok policies.▼4 Meanwhile, at the level of local governments, there is a continued need for a department that will be exclusively in charge of management objects similar to architectural assets. Even the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG), which runs the ‘Hanok Architectural Assets Division’ in charge of hanok and other architectural assets; future heritage, which falls under the category of architectural assets, and ‘priority control targets’ of the Historic City Center Basic Plan, all managed by other divisions. In the short term, the local government should establish a department for architectural assets, which is in charge of the essential investigation, inventory management, and support. In the long term, it will be necessary to overcome the limitations of project promotion or the loss of heritage sites by integrating the work related to architectural assets, such as historical heritage, architectural assets, and future heritage, into one division.▼5

The Support and Preservation of Architectural Assets

The Act on Architectural Assets adopts a strong stance as a supportive law that avoids a museum-style preservation of architectural assets and induces ‘use’ that can be employed in contemporary life. To efficiently use and manage a vast number of architectural assets, it focuses on indirect support softens connected regulations such as the building-to-land ratio, building lines, fire protection, and parking lots, rather than direct public financial support. It requires that direct support for the construction of new hanok and the renovation of architectural assets be operated according to the conditions of local governments. Conceptually, direct support from the state or local governments focuses on maintaining infrastructure such as roads, transportation facilities, water and sewage facilities, parking lots and support for the renovation and repair of historic buildings. In contrast, the law provides supportive regulations for the business entity and consultative body, tax reduction or exemption, technical assistance. However, there is no solid support for tax reduction because there are no tax-related legal regulations.

The preservation methods proposed in the Act On Architectural Assets engender the voluntary participation of owners rather than coercion or setting out regulations.Much like the hanok registration system, if the owner applies directly and registers their structure as an exceptional architectural asset, construction regulations will be eased or repair costs will be provided on condition of complying with the grace period for demolition.

Meanwhile, national support projects related to architectural assets include the Korea Hanok Competition, expert training programme and architectural asset based urban regeneration project conducted by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). The urban regeneration project is included as a type of cooperative project of government division. However, since the leading agent is MOLIT, there is a limit to promoting the urban regeneration project outlined specifically for architectural assets as it proceeds without any substantial additional budget support. Local government projects mainly include support for repair costs and subsidies for hanok construction, largely centred on Seoul and Jeonju. Renovation and repair support projects for modern buildings have also been partially carried out, such as in Jung-gu, Daegu. However, there is a limitation in that they are temporarily carried out by relying on state support projects, such as urban vitality enhancement projects and urban regeneration projects.

Policy Implementation Status and Performance

As of June 2021, six years after the law came into force, a total of 13 exceptional architectural assets were recognised by owners directly applying for building assets, and 13 were designated as falling within the architectural asset value enhancement zone. Except for the Maehyang-ri Koon-ni Range, registered as the first exceptional architectural asset in Korea, all are exceptional architectural assets in Seoul, and the SMG has designated nine out of 13 architectural asset value enhancement zones. Architectural assets policies based on this law and voluntary participation of owners can be said to be insignificant except for some local governments. Chebu-dong Holiness Church, Seoul’s exceptional architectural assets No. 1, was purchased by the SMG and has been renovated and repaired with the relaxation of building to land ratio, building lines, and attached parking lot installation regulations and is currently being used as the Chebu-dong Living Culture Support Center. Moreover, the No. 2 Daesun Flour Mills site is also planned to be developed as a complex cultural space by applying exceptional architectural asset to sidestep parking lot installation regulations. Maehyang-ri Koon-ni Range was also designated as an exceptional architectural asset by Hwaseong City, and it was opened as Maehyang-ri Peace Ecological Park in September last year.

Future Policy Direction and Tasks

The enactment of the Act on Architectural Assets can be meaningful because the state recognised the preservation value of our architectural assets. However, as an inducement through support rather than a compulsory regulation concerning conservation, the choice of whether to keep architectural assets and continue to use them can still be left to the owner. Recently, best practices have emerged in which the private sector directly drew upon architectural assets, such as Incheon COSMO 40, Yeongdeungpo Daesun Flour Mills, Seongsu Yeonbang, GongGongIlHo (formerly Samtoh Building). Daesun Flour Mills is the only case in which the architectural assets system was recognised and applied to an exceptional architectural asset in the process of being developed as a complex cultural facility. Other cases prompt questions about the need for various supports, expressing difficulties in preservation and using architectural assets in terms of their operation, such as a renovation or profit creation. The preservation of building assets needs to be made possible through the engagement of the private sector in this way. It is why we need to listen to their actions and voices.

Although changes are taking place that give importance to architectural heritage’s historical, living, and cultural values, the economic value still cannot be ignored. To this end, more diverse activities and policies are needed to broaden awareness of architectural assets. Another way is attracting public responses through architecture-related events such as the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism and the OPEN HOUSE programme. At the same time, it is necessary to locate the practical support measures desired by owners, discover effective ways of securing financial resources, and to build a system that can generate real estate profits. These include the promotion of the transfer of development rights to compensate for the economic loss caused by tax reduction or low floor area ratio, support for loans for operation and renovation, and the realisation of tax reductions and exemptions. Most of the architectural assets are low-rise, so it is a challenge to increase the effectiveness of the law and preserve valuable architectural assets.

(top) Yeongdeungpo Daesun Flour Mills ©Kim Yongkwan

(bottom) Maehyang-ri Koon-ni Range / Image courtesy of Architecture & Urban Research Institute

-

1 The ‘Seoul Future Heritage’ operated by SMG is a system drawn from the institutional sphere.

2 In this sense, architectural assets can be understood as more comprehensive than cultural assets. However, to avoid duplication and conflict with connected legislation, cultural assets designated and registered under the Cultural Heritage Protection Act are excluded from architectural assets.

3 UNESCO defines heritage as ‘our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations’. While ‘heritage’ is a concept that focuses on preserving the original form of high-value objects such as cultural assets, ‘asset’ refers to objects that can create added value through preservation and improvement in consideration of their future potential. ‘Resource’ is a concept that encompasses objects used in human life and economic production.

4 The Architecture & Urban Research Institute National Hanok Center is designated as a statutory institution under this regulation (Article 20 of the Act).

5 Sim Kyungmi et al., ‘A Study on the National Support Policy Plan for the Management and Utilisation of Architectural Assets’, Architecture & Urban Research Institute, 2019, pp. 51 – 52.