From AutoCAD to parametric and algorithmic design, digital technology has made major advancements and developed new expertise in the architectural world. However, as ‘drawing’ – the medium that has divided ‘design’ and ‘construction’ since Alberti – was gradually replaced by simulation, the working area of architects is now under threaten. In this context, David Ross Scheer diagnosed our current situation as the age of ‘the death of drawing’ in his book The Death of Drawing: Architecture in the Age of Simulation (2014). Seven years after its publication, this book has been translated into Korean and this translation was published last October. SPACE interviewed the translator Lee Junseok (professor, Myongji University) to consider what drawing means today for an architect, and what impact has such technological advancement had on architectural work and education.

interview Lee Junseok professor, Myongji University × Bang Yukyung

ⓒBang Yukyung

Bang Yukyung (Bang): The Death of Drawing: Architecture in the Age of Simulation is a rich and well researched study of drawing – that is, drawing as the architect’s primary tool of expression – and documents the changes to this medium. I’m curious to know how you came to translate this work on such a topic despite the obstacles to finding a study of this nature in Korea.

Lee Junseok (Lee): When I visited London on a business trip for the Korea Architectural Accrediting Board (KAAB), I randomly came across this book while perusing a bookstore managed by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). As I was pondering a suitable means by which to teach this topic to my students, I was very excited when I discovered this book. Upon returning to Korea, I contacted an publishing company with whom I was acquainted to propose its publication.

Bang: What led you to feel that it ought to be translated and published?

Lee: I have taught design to university students for more than 20 years. In all of my classes, aside from the improvements in design techniques among students, I felt that there was still a relative lack of understanding in terms of general education and theory. The students lacked especially the ability to understand and grasp individual works. As Korea’s architectural education is founded upon the engineering sciences, its curriculum is relatively less robust in terms of education on design theory or architectural history when compared to the educational system in the US or Europe. There is a need for students to deeply engage with theory and historical examples in architectural history classes and have them train visualisation skills regarding representation through design classes. However, due to the insufficiency of the curriculum, students tend to dismiss the importance of eye-hand coordination when it comes to perceiving and representing architecture. One cannot truly learn how to represent oneself through an approach that merely skims the surface. In this context, I felt that the topic and the questions and controversies raised by this book, particularly regarding architectural ‘representation’, is an pressing concern for the architectural realm and for architectural education in Korea.

Bang: This book suggests that the foundations of the architectural profession are being undermined by the introduction of technology—that is, simulation. It is replacing drawing, which was traditionally conceived as the exclusive realm of architects. As someone who has worked as an architect and now teaches, what are your views?

Lee: The author David Ross Scheer is an architect and educator who is currently active and working in the US. He is also an innovative architect, who incorporated the concept of Building Information Modeling (BIM) into his work at the end of the 1990s when it was only just beginning to catch on in the US. The fact that someone with this story is here testifying from his own experience about the challenges and threats posed to the working area of architects, due to the radical nature and pace of technological advancements, felt very real to me. The charms of designing, and the position and status that one holds over the design and construction processes—aren’t those the things that most architecture students dream of as they engage in their studies? The truth, however, is that the public view toward architects is changing, and we architects – and even universities that produce architects – are lamentably unaware of this threat. This is why I think that this book, which was originally published in 2014, is still pertinent today.

Bang: The first two chapters of this book explore the relationship between representation and simulation, and drawing and architecture, from a historical perspective. What specific significance does drawing have for architecture?

Lee: In architecture, ‘drawing’ is both a tool and an outcome that represents the architect’s intentions. Here, the ability to approach the problem creatively through ‘design thinking’ is especially important. To propose the problem, solution, and process in form, a high level of proficiency in visual training and talent is required. From the Renaissance to the contemporary era, architects have been thought of as people who draw with a level of expert ‘craftsmanship’. As architects retained control over both ‘drawing’ and information, they were able to establish a clearly defined working area and status among their clients, builders, and other related parties.

Bang: The author uses various examples to introduce a situation in which simulation has replaced the role of drawing. What is simulation and how is it used in architecture?

Lee: As a digital model that substitutes reality with experience, architectural simulation translates the coordinates of architectural planning from the virtual realm to the language of performance and experience. The two simulation tools used generally in architecture are BIM and computational design. Digital technology was first incorporated with the early AutoCAD program that produces simple drawings. In my personal experience, while I was required to draw by hand during my studies in the US, I switched to computer drawings when embarking on my professional career in 1995. The reason behind BIM’s development lies in ‘performance’. This is because the US General Service Administration in the early 2000s announced that all large-scale public projects must be based on BIM to improve building management efficiency. The changes brought about by BIM had a huge impact on the design process. However, what truly threatened the architectural profession was computational design as it allowed computers to create forms using self-made calculations. A certain amount of input data is entered, and the design emerges as an output. The architect who promoted a new design theory based on its development and use is Greg Lynn.

ⓒBang Yukyung

Bang: One could say that all of the representations produced during architectural design, ranging from making sketches, diagrams, and finalisation, are all drawings. And it seems like the act of drawing cannot but be affected by the property of the medium used. It seems like, along with the changes to medium from pen and paper to computers, there will also be changes in the way one thinks?

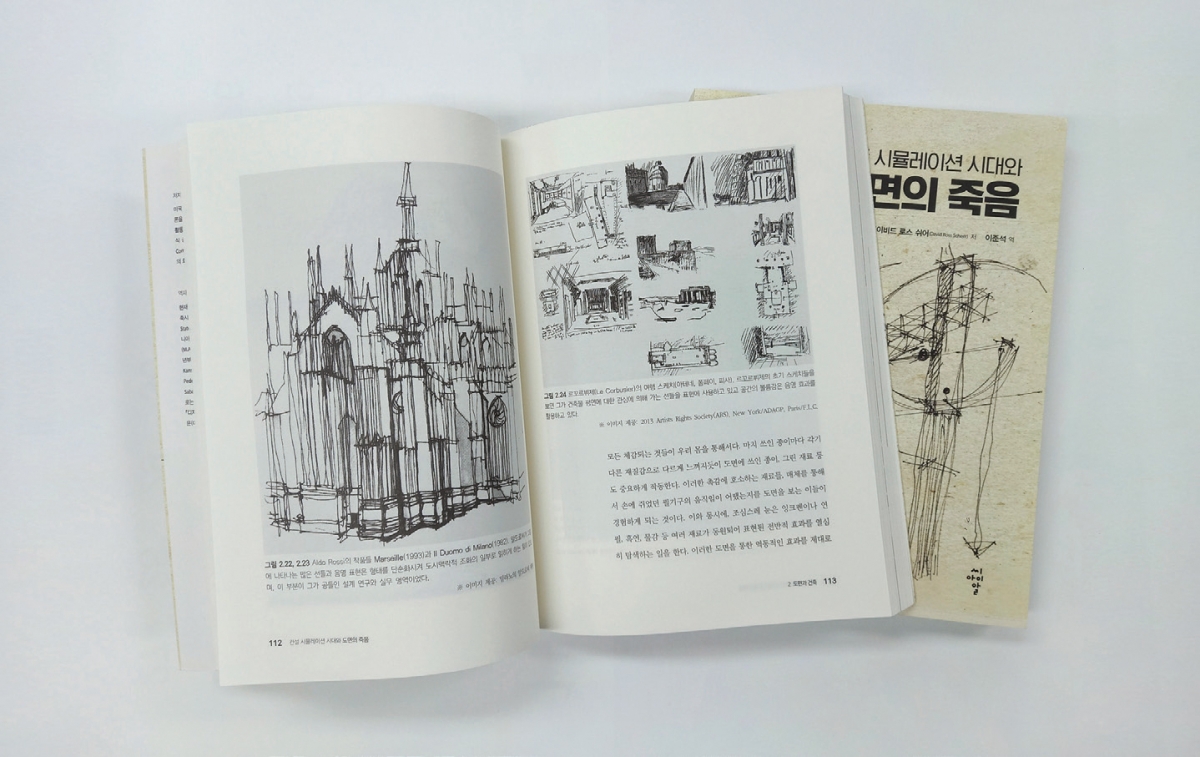

Lee: According to Francis D. K. Ching, and the argument pursued in his co-authored textbook Design Drawing (1998) – a book commonly used in architecture schools across the US – creativity is produced as cognition conceives of something formally. The same idea is repeated in this book. When architects hold the pencil and draw something on paper, a new interpretation is created. As they express their idea as a ‘drawing’, it turns into a new kind of representation from what was originally conceived, and this in turn becomes the seed for another creative idea. Although I live in an era in which computers are already employed at the earliest stage of any design, I still believe that traditional methods based on ‘representation’ will not disappear altogether. There cannot be anything but an uncrossable gap between the act of thinking and creating on a monitor screen and the act of developing the idea by hand. That is why architecture students must take the course, design practice by hand, at the early stage of 5-year curriculum in the school of architecture.

Bang: I heard that you are currently lecturing on a course titled ‘Art of Architectural Presentation’. How is this idea practiced in universities?

Lee: The course Art of Architectural Presentation is a class tailored to junior and senior undergraduates. While preparing this course, I set myself two aims: first, to expose the students to as many of the historical achievements in architectural drawing as possible, and second, to teach them about the cognitive process behind visual presentation, which shares similarities with Gestalt theory. The working results of architects are shared through their drawings. I noticed that the more I show my students the wonderful drawings from Gothic to contemporary architecture embodying this principle, the more profoundly engaged my students become. As with the visual training conducted at the Bauhaus, it is a crucial part of the course that students understand the visual mechanisms whereby these results are represented and realised. The final exam on this course is to create representations related to their design work.

Bang: The title, ‘Death of Drawing’, sounds somewhat portentous. What future does the author ultimately envisage in this book for architecture and architects?

Lee: To go straight to the conclusion, the author closes the book with the claim that ‘the role of architects will become more important in the era of simulation, and this is something which the architect has to discover by oneself.’ This is because no matter how digital technology develops, the final decision and responsibility for the design must lie with someone, and even in the most computer-intensive work there is still room for ‘craftsmanship’. While it may be the case that the role of architects is somewhat dispersed due to digital technology, Scheer firmly believes however that the core function, based on the ability to conduct ‘design thinking’, still resides within the exclusive realm of architects. As such, ‘Death of Drawing’ does not mean ‘there is no longer a place for architects’, but rather that there continues to be an impetus to establish an awareness of the problem and with it a platform for active debate and discussion.

Bang: What do you think is this book’s message for Korea’s architectural realm today? As its translator, what do you hope to realise?

Lee: With advancements made in simulation technology based on ‘performance’ values such as economy and efficiency, collaborations across borders between clients, developers, constructors, and various bodies are more and more popular in architecture projects. There is an urgent need for a mutually respectful and healthy discussion that understands the roles occupied by each party. To do this, realms such as architectural education, design, theory, construction, and technology need to cooperate and prepare themselves to usher in a new era of collaboration. Also, in spite of the progress in digital technology, we are becoming more aware of issues that cannot be quantitatively evaluated such as matters concerning ‘value’ and ethical judgments. In this sense, it is a time for us to actively define new roles and positions of leadership demanded of the ‘architect’ in this era.