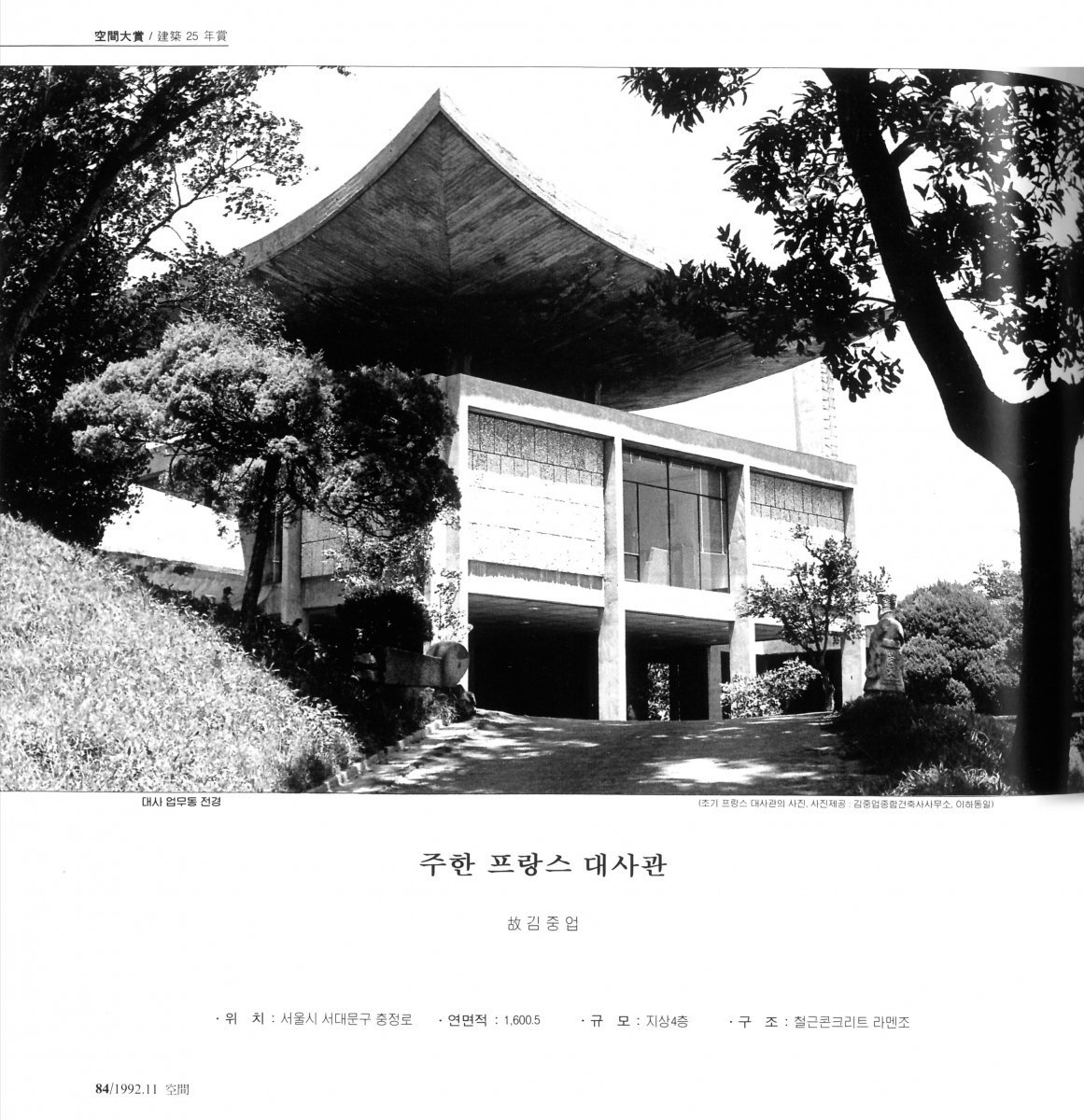

The cover of SPACE No. 302 (Nov. 1992)

Constructed in 1961, the French Embassy in Korea (hereinafter French Embassy) designed by Kim Chung-up is legendary in contemporary Korean architecture. This status is not simply because of the excellent formation of the building—the characteristics of the building as a foreign diplomatic office, where the visitor access is strictly controlled, played an important role as well as the distinction of the design itself. The French Embassy, which is revered as a representative work by Kim and a masterpiece in Korean architecture, has long been a building that many people wish to visit but many have not been able access for a long time. It was a great privilege to visit and look around the building. We could only access the French Embassy through the reproduction of media. SPACE has played a crucial role in producing and distributing influential words and images on the building. The editions which featured the French Embassy in detail are the No. 5 (Mar. 1967) and No. 224 (Mar. 1986) with Kim Chung-up specials, the No. 227 (June 1986) with the obituary of Kim, and the No. 302 (Nov. 1992) and the No. 552 (Nov. 2013), which dealt with the building’s receipt of architecture awards. The special feature dealing with the new construction and renovation of the French Embassy is included in this issue, No. 649 (FRAME). A fully-fledged historical critique of the French Embassy was attempted in November 1992, in issue No. 302, which was produced in celebration of the SPACE TIME Award. Marking its 300th issue, SPACE established an architecture award for buildings that had stood for more than a quarter of a century. The French Embassy was the first winner of the SPACE TIME Award, celebrating work that has passed the test of time over the short history of modern Korean architecture.▼1 For the judges, Kim Kwanghyun, Kim Bongryol, Park Gilryong, and Yim Changbok published commentary essays on the French Embassy. Of course, there are existing studies on the architect and the world of his work, but it is noteworthy that such prominent scholars and critics wrote lengthy critical appreciations of a specific building.

The French Embassy in Korea in ʻThe 1st SPACE TIME Award’, SPACE No. 302, p. 84.

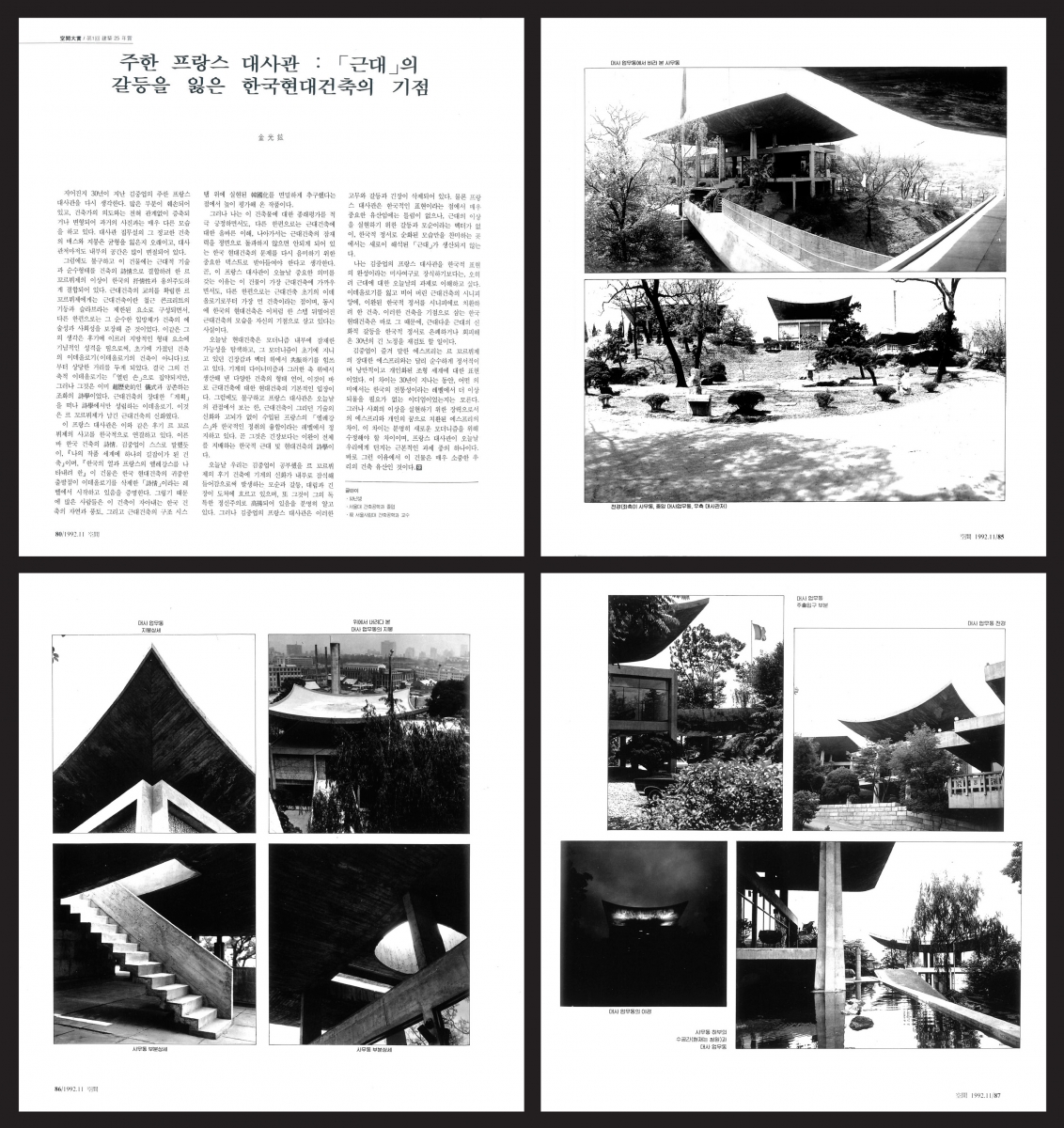

These four articles, which established the French Embassy as an origin of modern Korean architecture, provide an essential framework for discussion of the building. First of all, Park Gilryong’s essay attends to the purpose of the study in that it attempted a detailed and specific analysis of the form and space of the embassy buildings. Notably, it draws a dramatic contrast in the form of different roofs of the embassy residence and the ambassador office building and captures the resonance created by the structures arranged with opposite axes. Yim Changbok compares and analyses the French Embassy and the buildings of Le Corbusier. Yim aims to guarantee the legitimacy of the origins of contemporary Korean architecture by proving that Kim did not simply imitate Le Corbusier’s architecture but exposed a unique creative approach different to that of his master. The discussion of the architecture of Kim and the influence of Le Corbusier intitiated a more empirical and objective point of view by following researchers, including Jung Inha. Kim Bongryol, a traditional architecture researcher, reexamines traditional discours in contemporary Korean architecture using the the French Embassy as a lens. He resets the starting point and direction of the debate on tradition, stating an expression of Koreanness attempted by Kim Chung-up was not a copy or simple transformation of traditional architecture, as in the ʻtradition argument’ in the mid- 1960s, but was tried at a more fundamental, lyrical, and spiritual level. Meanwhile, Kim Kwanghyun’s article differs from the previous three essays in that it critiques the historical significance of the French Embassy and its limitations. Kim acknowledged that the embassy buildings were a triumph achieved under harsh conditions. However, he also pointed out that admiration for the building that combines ʻFrench elegance and Korean sentiment’ merely concealed ʻthe absence of consideration and the myth of technology in modern architecture’ with the rhetoric of Korean expression. Moreover, he finds the contradictions and distortions faced by Korean architecture in that the French Embassy is the starting point of modern Korean architecture, which is far from the early modern architecture theory. This criticism is understandable if one recalls Kim’s commitment to rediscovering the zeitgeist of modern architecture with 4.3 Group architects of the time.

The interpretations of the four critics differ in their point of view and interests, but they all emphasise Kim Chung-up’s architecture as archetypal before the extension and transformation. They lamented that the embassy had changed from the original they had seen in photos when they visited the embassy site to select the winner of the SPACE TIME Award. Kim Kwanghyun regretted that the repeated phases of extension and transformation which deviated from the architect’s design resulted in a loss of the ʻmass and balance in a delicate work of architecture’, while Kim Bongryol also described its transformation as a ʻtragedy’. Let us consider the second half of the essay by Park, which demonstrates the most intense reaction:

ʻAs I witness how the architecture deteriorated, damaged, and aged over the course of 30 years, I felt as if ecology was breathing exhaustedly. How many buildings have we harmed so far simply as a consequence of unclear use? As with our lack of appreciation for life, we either hurt, burden, erase or distort architecture. It is also our duty to the history that this building removes its scars immediately, allows it to breathe more comfortably, and restores the wounds to rest.’ ▼2

The article of Kim Kwanghyun and photos of the French Embassy in Korea in ʻThe 1st SPACE TIME Award’, SPACE No. 302, pp. 80; 85 ‒ 87.

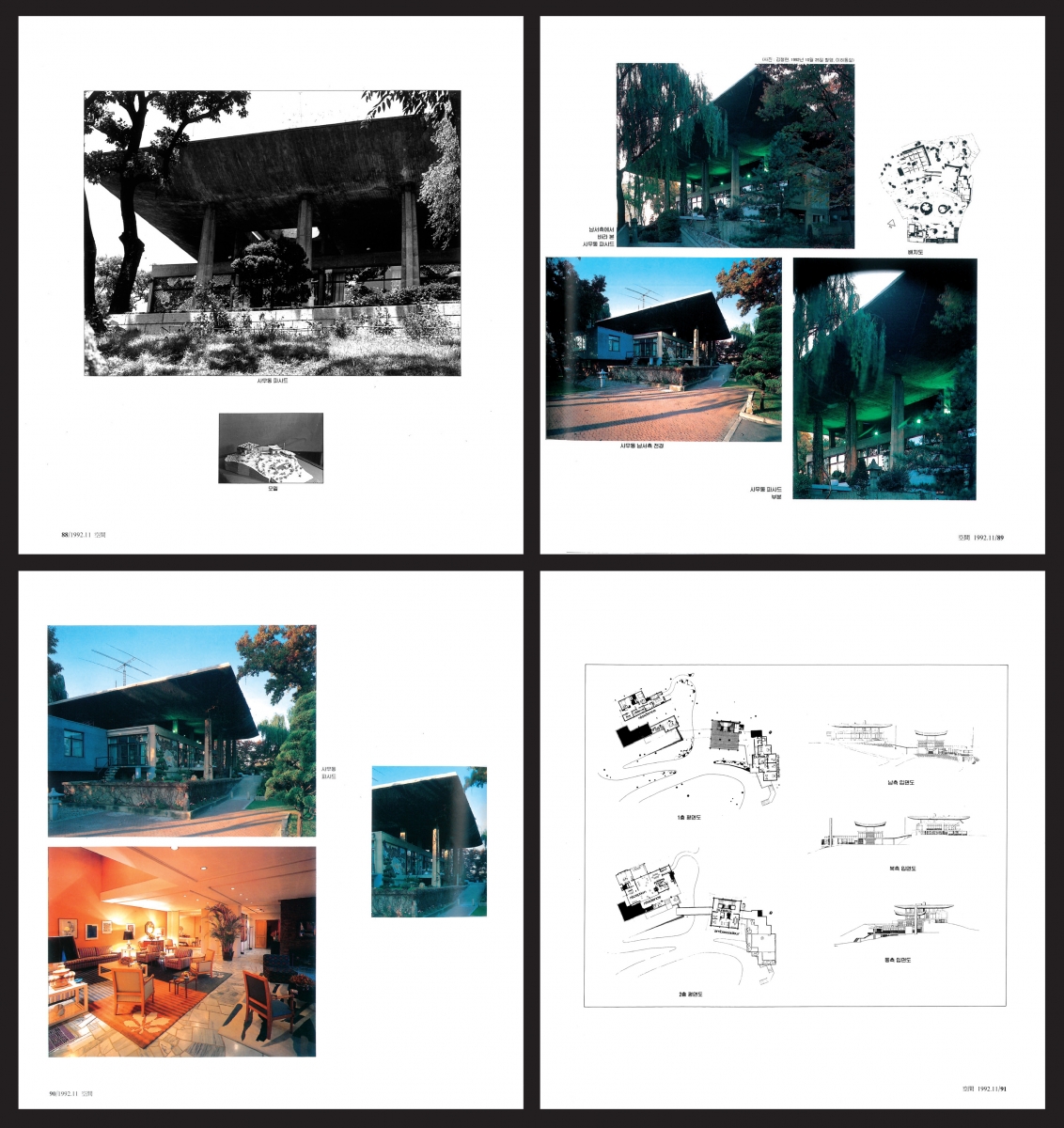

The photos and drawings of the French Embassy in Korea in ʻThe 1st SPACE TIME Award’, SPACE No. 302, pp. 88 ‒ 91.

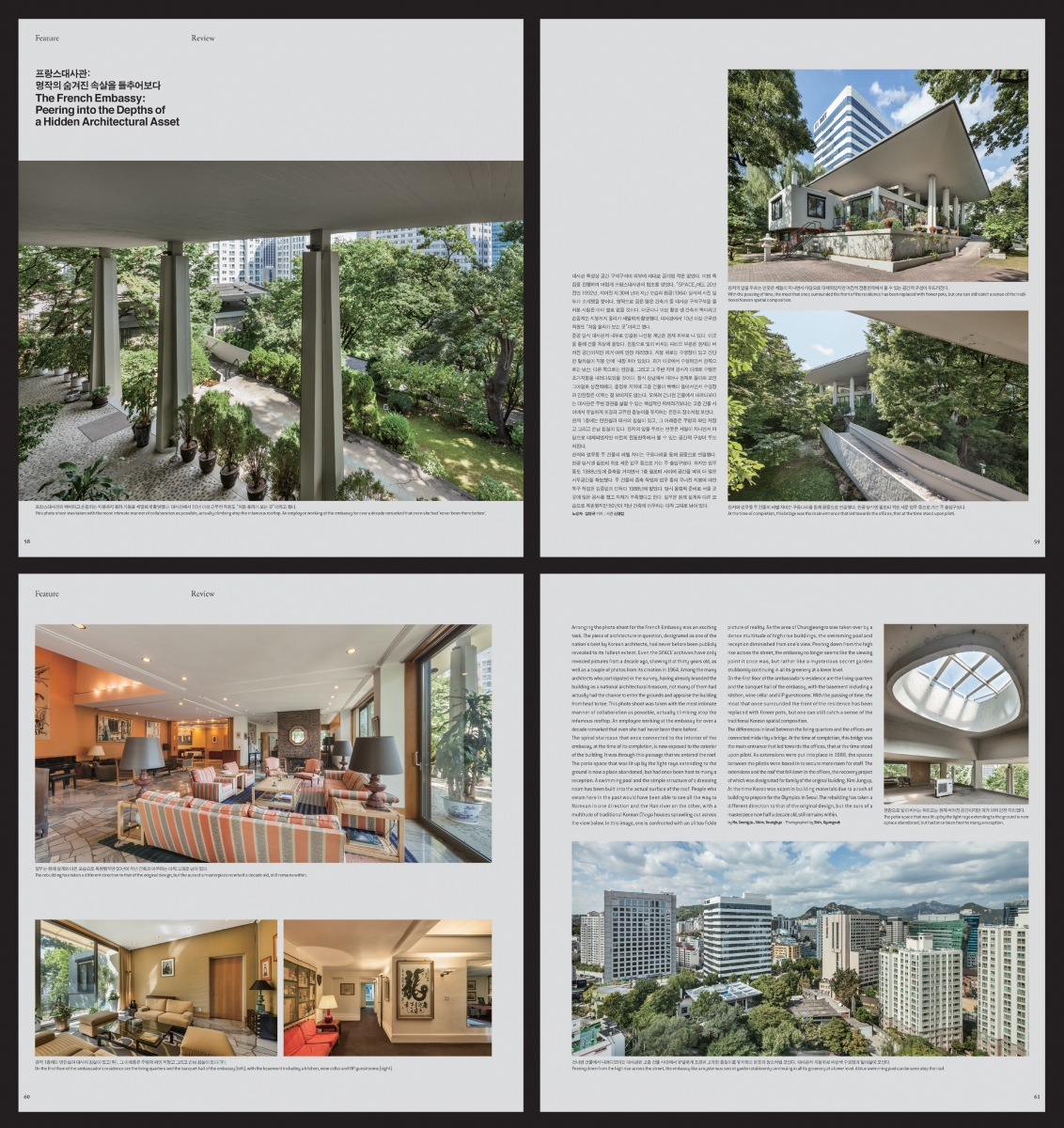

So, how far was the French Embassy from its 1992 original form? Among the French Embassy complex, which consists of the embassy residence, the ambassador office building, and the staff office building, the only building that has not experienced significant change is the embassy residence. In 1988, it was enlarged to solve the shortage of space, and at that time, it added offices by filling the lower part of the pilotis of the ambassador office building and extended the staff office building. The biggest change was the replacement of the roof, which had been worshipped as a symbol of Korean curves, in a flat and angular form while repairing the ambassador office building that had caved in due to the construction problems in the late 1970s. The exact timing is not precise, but the appearance of the gardens carefully arranged by Kim, including the pond surrounding the embassy residence, has been changed, a new security office building was built, and the existing internal spaces have also changed to suit the needs. The embassy residence, which has experienced relatively slight changes in its appearance, has also undergone changes, such as the closure of the rooftop garden, where people could enjoy swimming with the scenery of the urban landscape.▼3 As such, the French Embassy has changed from its original appearance, but at least photos in the SPACE bring the whole embassy back to its full form, which we no longer see. The embassy residence and the ambassador office building in the picture carve into the sky with their overlapping rooflines. Along with the majestic view of the ambassador office building lightly sitting on the pilotis, the very Korean roofline is captured in close-up. These black-and-white photos right after the completion in 1961 were widely distributed as images representing the timelessness of the French Embassy. SPACE No. 302 includes six new colour photos were taken by photographer Kim Cheolhyeon in 1992 at the embassy’s good consideration, as well as those black- and-white pictures in 1961. Interestingly, the colour photos were taken to show the current appearance of the building, only capturing the embassy residence with minor modifications and intentionally excluded the ambassador office building and the staff office building from the frame. This selective reproduction is repeated afterwards. Finally, let us look to SPACE No. 552, which featured the selection of the French Embassy as one of ʻThe Thirty Masterpieces of Korean Contemporary Architecture’ in 2013. This issue composed the pages only with colour images taken by photographer Kyungsub Shin and delivered the changed appearance of the embassy. Seven out of eight colour photos reveal the interior and exterior of the embassy complex, while none of the individual images of the ambassador office and the staff office buildings was published. However, the ambassador office building’s changed roof can be glimpsed in one photograph, overlooking the embassy complex surrounded by the city’s forest of building to emphasise the changed urban context.

The long-standing call for the pure original form of the French Embassy seems to be bearing fruit in a recent new construction and renovation project. At first, the French government requested the preservation of only the official residence. However, the continued appeal of the Korean architecture community and the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism was accepted, and it was decided the the ambassador office building would be restored following the original design by Kim Chung-up. The design created by the MASS STUDIES and SATHY consists of the office tower ʻLa Tour de France’, which can bring together various embassy functions scattered throughout Seoul, and ʻLa Jetée’, access and gallery. La Tour de France and La Jetée resonate with existing buildings along the axis of the embassy residence and the ambassador office building, while highlighting the difference between the past and present, the design of Kim and MASS STUDIES and SATHY, and employing a contrast in colour and texture. When the new construction is completed in 2022, the French Embassy will be more open and accessible than the past. Although public access is still restricted due to the nature of an official foreign residence, anyone who works in the La Tour de France and La Jetée can see Kim’s buildings from a relatively close distance. How will the French Embassy’s status remain legendary when selective media representation no longer plays an exclusive role as in the past? One thing is sure: the French Embassy is no longer the building of Kim Chung-up. While the proposals of MASS STUDIES and SATHY preserve the historic architecture designed by Kim, they demonstrate a flexible and open attitude to the changing urban contexts and new needs around the embassy rather than sticking to the original form. (written by Cho Hyunjung / edited by Bang Yukyung)

In our next issue, Hyon-Sob Kim will cover the first issue of SPACE (Nov. 1966).

The ʻReview’ of the French Embassy in Korea in ʻThe Thirty Masterpieces of Korean Contemporary Architecture and What Came Next’, SPACE No. 552 (Nov. 2013), pp. 58 ‒ 61.

1 SPACE selected the SPACE TIME Award four times until 1999: the French Embassy by Kim Chung-up (1992), the Korean Catholic Martyrs’ Museum by Lee Heetae (1994), the Freedom Center by Kim Swoo Geun (1996), and the SPACE Group of Korea Building by Kim Swoo Geun (1999).

2 Park Gilryong, ʻThe Traditional, Space, and Rhetoric in the French Embassy in Korea’, SPACE, No. 302 (Nov. 1992), p. 82.

3 Relevant data, including the exact time and persons in charge of the damage, repair and extension of the building, do not remain, so it is difficult to grasp the historical changes that have altered the French Embassy in Korea.