Various agents, such as the Ministry of National Defense, Incheon Metropolitan City (IMC), Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), and other civic bodies, are in conflict over whether to demolish the hospital building of the Incheon Arsenal located in the Bupyeong Camp Market (hereinafter BCM), one of the returned US military bases. In a meeting with Lee Yeonkyung (research professor, Incheon National University) who has spent many years researching the returned US military base, SPACE discussed the controversies concerning demolition and what needs to be changed more broadly across the architectural field to resolve such issues.

interview Lee Yeonkyung research professor, Incheon National University × Bang Yukyung

Current view of the Bupyeong Camp Market area (Hello ASCOM City, Goodbye Camp Market – The Story of the Bupyeong US Military Base and the People of Bupyeong, Bupyeong Museum of History, 2020). Image courtesy of Bupyeong History Museum

Bang Yukyung (Bang): Several points of controversy have arisen over whether to demolish the hospital building of Incheon Arsenal in the BCM. Before we begin, what is Incheon Arsenal, and how was it formed?

Lee Yeonkyung (Lee): Incheon Arsenal was the first weapons manufacturing arsenal built in the colony by Japan (as opposed to on the Japanese mainland) and the first to manufacture weapons during the Asian- Pacific War. Its official name is ‘Incheon (Army) Arsenal’ and it was founded in 1941. The site of the Incheon Arsenal was the site of the Bupyeong training field used by the 20th division of the Japanese Army, a site active since the 1920s, and the surrounding area was developed as the Bupyeong district of the Kyeong-In Town Plan since 1939. To invite factories into the Bupyeong area, the Japanese Government-General of Korea and Dongyang Cheoksik Co., Ltd. lent funds at low- interest rates, and several companies with connections to the military industries such as Mitsubishi Steel Manufacturing and Tokyo Steel Manufacturing Co., Ltd. moved into the area. As a result, Bupyeong rapidly developed into a military-industrial city in just five years, from 1939 to 1944. Incheon Arsenal mostly manufactured firearms, and manpower for forced labour was also conscripted at the same time. As such, housing complexes to accommodate the influx of workers were quickly constructed around the factories. The well-known Mitsubishi row housing was the first housing complex to be introduced near the Incheon Arsenal. In the Sangok-dong area, near the main site, there are still more than a thousand houses were built at that time.

Bang: The Incheon Arsenal is now being used as the BCM. I believe it is also important to revisit the history if the site since the US military moved in and were stationed there. What processes of change did it go through?

Lee: After liberation, the US 24th Corps took over the area near Incheon Arsenal, including the military factories. Since then, for most of the time excepting during the Korean War,

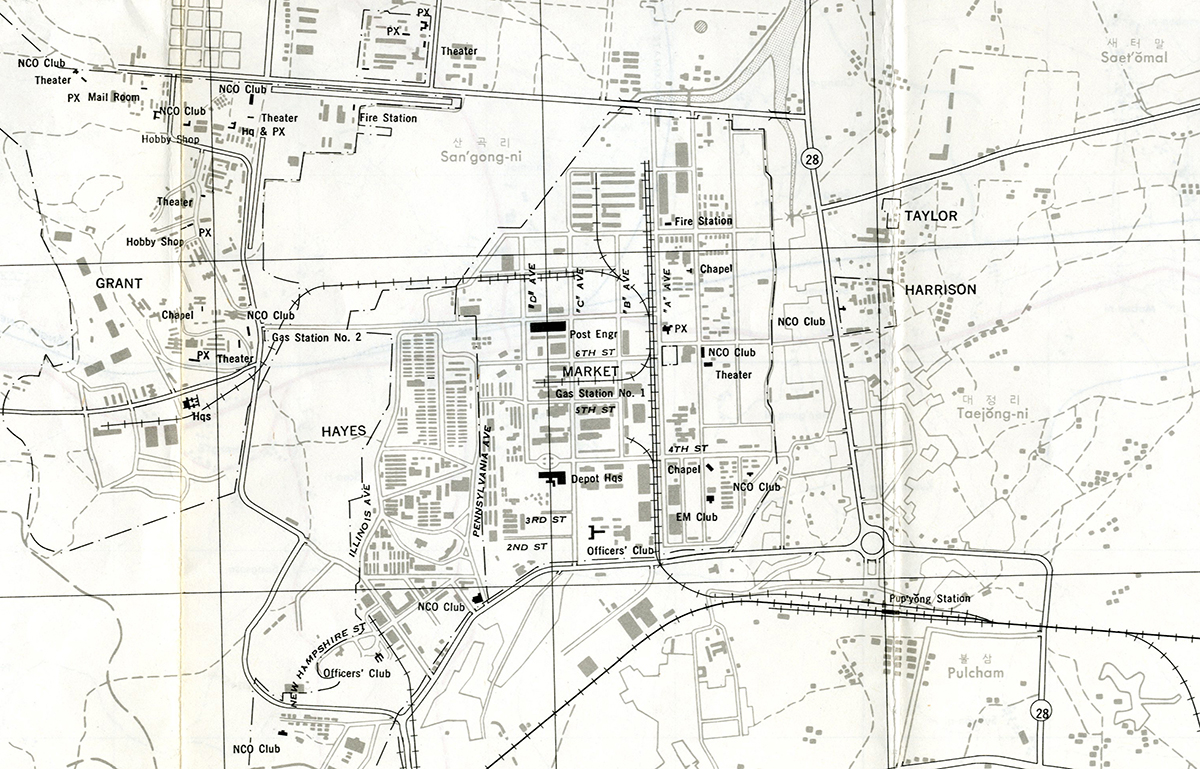

the Incheon Arsenal was used as a main US military base for stationing in South Korea. It’s important to note that when the Army Service Command was stationed in 1955, the US military renamed it the Bupyeong US military base (consisting of seven camps), which was responsible for the production and distribution of military supplies, as ‘ASCOM City (Army Service Command City)’. However, the most significant functions of the base moved to Yongsan in the early 1970s. Therefore, ASCOM City was disbanded in 1973, and its area reduced to the current area of the BCM. The voices of those advocating for the return of the US military base, which occupied the area of Incheon Arsenal for more than 70 years, rose in volume in 1996, when the Movement for the Return of Bupyeong US Military Base was galvanised by environmental groups. After that, the decision to relocate the US military to Pyeongtaek was confirmed, and the ‘return of the BCM’ was realised. At present, the US military is returning the BCM partially by dividing it into zones A to D according to the Korea-US Land Partnership Plan (LPP) signed in 2002. Of the site of the entire BCM (440,000m2), zones A and B (210,000m2) were returned first in December 2019, and the remaining zone D (230,000m2) will be returned in April 2022 after discussing the shutdown and relocation of the baking factory.

Bang: Ever since the IMC decided to demolish the hospital building of Incheon Arsenal in the BCM in this June, various news media outlets expressed their concern that it might destroy any evidence of Japan’s forced mobilisation. What followed was a national petition posted on the Cheong Wa Dae (presidential Blue House) website, requesting the preservation of the hospital building as a historical heritage site. As a consequence, in August, IMC decided to postpone the decision to demolish the building. Why did this controversy arise considering that the military base is being returned?

Lee: This is because the decision to demolish the BCM was made without proper investigation or research into its historical and architectural values. Prior to the return of the military base, the CHA recommended the preservation of the building. However, unlike the Cultural Heritage Excavation Act, a ‘recommendation’ does not carry any legal obligation. The building subject to controversy today is ‘Building No. 1780’ located in zone B, as most of the buildings in zone B except for this building have been destroyed. Some interested parties question whether Building No. 1780 was really used as a hospital during the period of Incheon Arsenal, putting pressure on the identification of its architectural and historical values. But this is a spurious argument. It is impossible to prove its value when there hasn’t been any formal investigation or research conducted on the buildings of Incheon Arsenal. Of course, there is sufficient data, such as the testimonies of residents, related records, and previous research data, to prove that the building was a hospital. Yet, in order to go beyond confirmation of the fact that it was a ‘hospital’ and to clarify its value accurately, there has to be a thorough investigation. Administrative assistance is required to conduct such an investigation, particularly when it is difficult to get support from the US military base due associated questions of military security, secrecy, and safety. However, it is difficult at present to obtain cooperation for such investigative efforts and research projects.

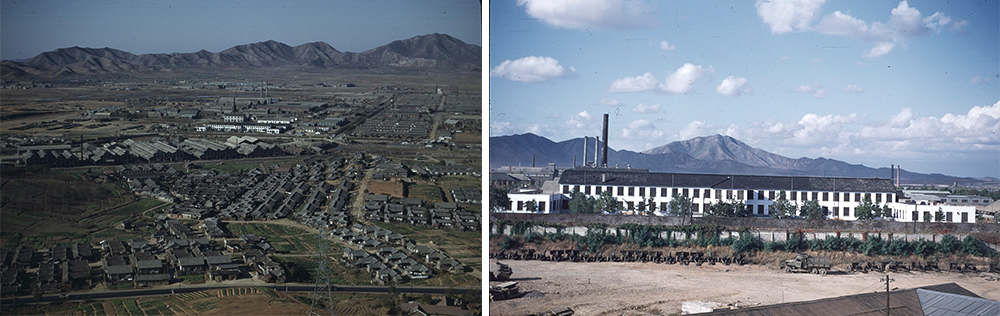

The area around the Incheon (Army) Arsenal and hospital building photographed in 1948 ©Norb Faye / Image courtesy of flickr

Bang: What are the main arguments and issues for those advocating demolition?

Lee: I believe both environmental and economic issues are provoking controversy. The cost and time involved in the reduction of pollution are also important issues. In general, the most convenient method is to remove the facility and to purify the soil. There is also a means of limiting pollution while maintaining the facility, but in this requires more time and greater investment. Therefore, those who advocate demolition want to remove the facility and to purify the environment as quickly and economically as possible. And yet, a significant historic site cannot be recreated once it is erased. Even if it takes more time and cost, we must actively seek alternatives.

Bang: I think a substantial number of US military bases, other than the BCM, are being returned to South Korea. What is the situation in these cases?

Lee: Currently, a series of processes is repeated across different US military bases nationwide, as well as at the BCM. Since most of the returned US military bases are being used as parks, each municipal and provincial government seems to have rushed into planning the park without properly investigating the historical value of these sites. In the case of the well-known Yongsan US military base, a thorough investigation of 1,200 facilities in the military base has been conducted under the leadership of the CHA since 2011 prior to the construction of a park. Since that moment, experts from across various fields have gathered to evaluate the value of the facility from different angles, ruminating on ways to preserve and use the existing facilities. In order to decide whether or not to demolish and to discuss ways of best using them, isn’t it necessary to establish a master plan and to implement a project based on such thorough investigations? However, Yongsan was a ‘very special’ case even in South Korea. Except for Yongsan, the process of the return of US military bases such as Busan Camp Hialeah, Wonju Camp Long, and Hwaseong Koon-ni Range have mostly followed ‘pre-planning and post-investigation’ rather than ‘pre-investigation and post- planning’. Conversely, there are substantial instances in which the process of investigation and research is carried out for the purpose of a ‘documentation project for demolition’.

Bang: As an architectural expert conducting research related to US military bases in South Korea, what are the primary values of BCM?

Lee: Due to the nature of military architecture, one that pursues efficiency and function, it is difficult to evaluate buildings on a US military base based on architectural values such as style and a sense of form. Rather, it is more feasible to discuss their historical value and how that captures a particular era; this can be roughly divided into three categories. The first is its value as a remnant of the Asia-Pacific War. As a weapon manufacturing factory during the Asia-Pacific War, Incheon Arsenal represents a highpoint of architecture during wartime. It is a large-scale reinforced concrete building erected by exploiting all available resources under the restriction on supplies during the war (National Mobilization Law) that conscripted even brass vessels and spoons from house to house. The second is its value as core space that impelled the formation and development of the city Bupyeong, which played a vital role in the industrialisation of South Korea. The history of ASCOM City and BCM, once occupying two-thirds of the area of Bupyeong, represents the history of Bupyeong. Most of the urban resources and manpower were forged and operated in and around this space. In this way it displays an important sense of place in the study of Bupyeong’s urban and life history. The third is its value as a heritage site from the Cold War era following the Korean War. In compliance with special circumstances such as the division of Korea, the BCM is a symbolic place that retains a part of the history of the Cold War system intact, and illustrates its worth as a research subject not only domestically but also internationally. Just as the period Incheon Arsenal was used at the end of the Japanese colonial period is important, the period it was occupied by the US military should also be treated as crucial. When looking only at the period of occupancy, the Japanese used it for six years while the US used it for more than 70 years. On a personal note, while studying several US military bases, I discovered that characteristics such as structure, material, method, and space continuously change from time to time. So before discussing whether to remove the site, I think there is an urgent need for more detailed investigation and research on US military bases.

Bang: Recently, a new fact related to the basement of Incheon Arsenal has been gradually revealed in the efforts of an individual researcher. It is good news, but it is unfortunate that research on the BCM is conducted in a sporadic fashion at the individual level rather than being integrated and combined.

Lee: Historian Cho Gun (researcher, Northeast Asian History Foundation) is conducting a research project through excavating documents regarding the plan of the underground facility of Incheon Arsenal at the end of the Japanese colonial period. We believe that this study will provide many clues to the use of the underground facility of the Incheon Arsenal that have not yet been revealed. Moreover, a cave called the Salted Shrimp Cave in Sangok-dong was built by the Japanese to hide weapons at the end of the Asian- Pacific War. The map of the 1948 US military records reveals the marks such as ‘CAVE 1, 2, 3…’. According to US military records, there are more than 40 locations. But as ASCOM City was reduced to the BCM in 1972, some of them were used by residents as Salted Shrimp Cave, some remained inside the South Korean military base, and some were lost while building houses. Currently, Bupyeong Cultural Center is investigating this cave, managing it as a historic and cultural resource. Bupyeong Cultural Center and Bupyeong History Museum have long been conducting living and cultural analysis and academic research into Incheon Arsenal and the Bupyeong area. However, as it became official that the military base was to be returned, the two institutions were excluded from the research project into the BCM. Then, when the ministries under IMC took charge, it became evident that the research on Incheon Arsenal was not being conducted in an integrated manner.

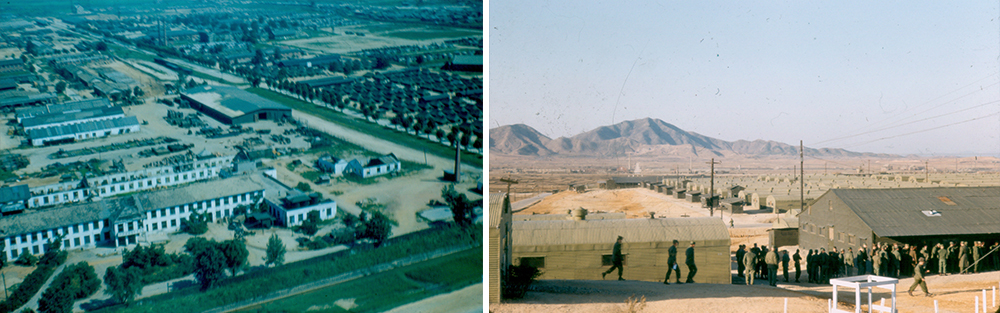

The ASCOM City area photographed in 1952 and US military’s map showing the deployment to ASCOM City in the 1960s. Image courtesy of Bupyeong History Museum

Bang: What do you think the fundamental reason for this series of controversies is? Where can we find clues to solve the problem?

Lee: The fundamental reason for the problem is the absence of governance. Haven’t we experienced enough of what happens when a city acquires a large available lot? In this specific case, concerning a returned US military base, there are bound to be a lot of stakeholders such as the Ministry of National Defense, CHA, IMC, Bupyeong-gu Office, and civic groups. On the outside, it may seem like this is a conflict between the preservation of cultural heritage and environmental pollution, but in fact it is a political battle over the nature of development. Of course, it is natural for stakeholders to have different opinions. I am also not saying that we should preserve every buildings. Yet, the controversy continues due to the lack of governance, which could play a role in publicising different perspectives and leading a decision-making process through discussion. Of course, in consideration of such roles, IMC organised the Citizen Participation Committee of the BCM in 2011, but there have only been a few actual meetings held, and a number of problems in the decision-making process.

Bang: The return of the BCM is currently ongoing. If we want to make sure that the case of the BCM does not become an example of demolition, how should the architectural field respond before and during the returning process?

Lee: What I talked about the most when I was involved in the BCM was the absence of a master plan. We need to establish an integrated master plan based on the results of a survey and research. At present, since the BCM is being partially returned according to divided zones, it is difficult to establish an overall plan. Yet, as in the case of Yongsan, an investigation can be conducted even before the military base is returned. The survey may not be the whole content of the master plan, but once this process is conducted, it is possible to set the direction of the park and determine whether or not the building will be preserved, along with the scope and the method of preservation. After that, doesn’t the rest depend on design? However, unfortunately, according to a recent update, most of the buildings in zones A and B have been demolished, and IMC has decided to let ministries use the remaining buildings in zone B. For instance, the Health and Sports Bureau will separately design and use the gym building, and the Culture and Tourism Bureau the enlisted restaurant.

Bang: How can we use the Incheon Arsenal building if we preserve it? What should we do to preserve and use the existing modern and contemporary cultural heritage sites, including the BCM, in the Incheon?

Lee: According to an employee at the Bupyeong History Museum, there are so many remaining elements connected to the Incheon Arsenal that it is impossible to store them all in storage. If we can use the hospital building as open storage, I think it would be an appropriate place to display aspects from the life of Incheon Arsenal and underline its social and historical value as war heritage. We could employ the terms and practices of industrial heritage as an architectural method in the use of the Incheon Arsenal building. Factory architecture, which places emphasis on function and efficiency, reveals the limits of time and technology. In a space of industrial heritage, people talk about the sense of an overwhelming context and the aesthetic of ruins presented by monumental factory architecture. Since the time and historical period centred in BCM is not exactly light, the same method cannot be applied. Yet we can consider remodeling it as a cultural space, as in the cases of Incheon Art Platform, Bucheon Art Bunker B39 and COSMO 40. In that set of circumstances, if the master plan can be linked with the Modern Historical and Cultural Heritage Sites projects (CHA) or the Idle Space Cultural Regeneration projects (Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism), it would be helpful to raise the financial resources.In Incheon, general cultural heritage or modern cultural heritage sites are concentrated in the open port of Jung-gu, whereas, in other areas except here, development-oriented projects are ongoing. Cultural heritage such as Dongyang Spinning Co. or Ilshin Electric in Dong-gu has not yet been designated as modern cultural heritage. Why does the administration adopt such a passive manner? Small towns in the region including Gunsan have no choice but to stress modern cultural heritage as the only driving force behind urban growth. But the situation in Incheon is different. There is a prevailing perception that modern cultural heritage is less useful when compared to the possible profit that could be obtained from real estate development—even if you pour taxes in, no clear results can be expected. Such an equation is also evident in numerical values. Currently, the number of Registered Cultural Heritage sites by the CHA across the country is over 900, but there are only eight cultural properties designated as such by the State in Incheon. Incheon is often criticised for its lack of human resources. I believe this imbalance will disappear only when more people study the preservation and use of modern cultural heritage in the region.

The current scenery of the Incheon (Army) Arsenal hospital building (It was reduced from a two-story building to a one-story building.) ©Lee Yeonkyung