The exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’, held in 2019 at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), points to ‘happiness’ as a new focus and concern for today’s architecture. Happiness, which used to be considered a very personal feeling and experience, now functions as part of the logic of the market economy, an ideology, and as a standard measurement within urban and national rankings. Two years later, in 2021, the exhibition opened at the Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture (Seoul HOUR) as an international exchange exhibition. How does architecture affect happiness and how does happiness affect architecture? SPACE spoke with the three curators of the exhibition: Francesco Garutti and Irene Chin of CCA and Kim Hyoeun of Seoul HOUR.

interview

Francesco Garutti curator, Canadian Centre for Architecture

Irene Chin curatorial assistant, Canadian Centre for Architecture

Kim Hyoeun senior curator, Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture

×

Choi Eunhwa

Choi Eunhwa (Choi): The exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’ was first held in 2019 at the CCA. It suggested that what architecture and the city should pay attention to now is no longer the experiment with form or type, but to emotional responses and the happiness of individuals and collectives. How did you start the exhibition?

Francesco Garutti (Garutti): The founder of CCA, Phyllis Lambert said ‘We’re not a museum that puts things out and says, “This is architecture”. We try to make people think.’ When CCA initiates the project, we often begin by exploring cultural transformations and looking for moments of friction. We identify what we call ‘grey areas’ from which we raise questions to better understand the role of architecture and design space production in society: such as the idea of progress, environment, health, technology and education. So I would say this mode of looking at society and raising urgent cultural questions through the lens of space, architecture and the city is always our starting point and our driving motivation.

Choi: What is the intention or reason behind why you chose ‘happiness’ from numerous emotions and feelings experienced by human being?

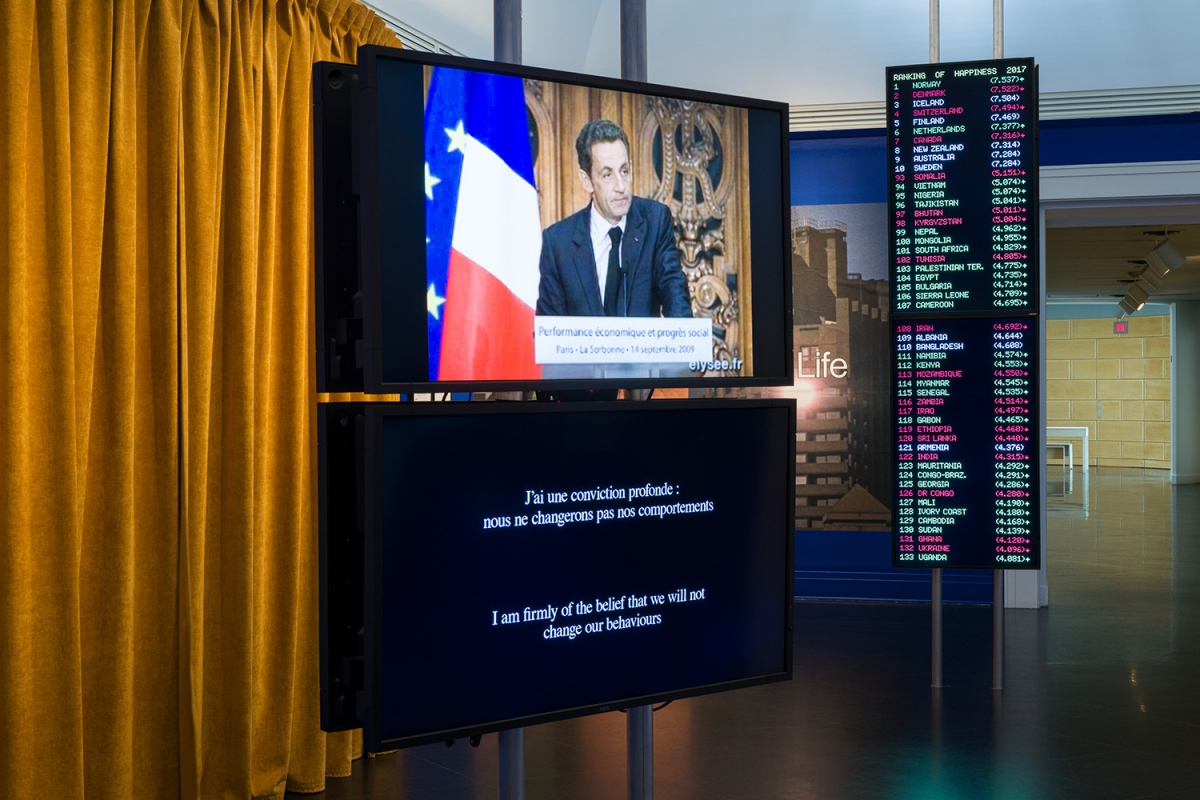

Garutti: ‘Happiness’ had entered political and economic discourse and the way it was used in the media, and this was of interest to us—the fact that it became the subject of speeches by Prime Ministers and resolutions in the United Nations, the fact that countries and cities were being ranked in lists and reports on quality-of-life really gained traction. The shift from wealth to well-being as a way of ‘measuring’ society after The 2008 Financial Crisis where the project begins to identify a redefinition of happiness and the emergence of an emotional capitalism in which feelings and experiences are instrumentalised. The exhibition presented how governments, economists, and social scientists have defined it through systems of metrics, surveys, and data. In this sense, you might say we approached it through a scientific lens rather than a philosophical one.

Still from Now, Please Think About Yesterday, a narrative documentary that closely observes the processes and people behind the design and execution of the Gallup World Poll and Global Emotions Report. Directed by Erin Weisgerber. Commissioned and produced by the CCA in 2019, as part of the exhibition 'Our Happy Life'. (ⓒCCA)

Choi: Is it possible to measure an immaterial happiness, which is both personal and collective (even national); subjective and objective?

Garutti: We explored through the documentary film, Now, Please Think About Yesterday. Gallup is an American analytics and consulting agency famous for its public opinion polls—they are the largest listening machine in the world related to World Happiness Report. With filmmaker Erin Weisberger, we visited their headquarters and call centre better understand the design and implementation of this critical tool that has evidently made it possible to measure happiness.

Irene Chin (Chin): With information gathered through the Gallup World Poll, governments started to observe and track this subjective data. Surpassing objective figures like mortality or graduation rates, notions of fulfillment came into play. Beyond measuring square footage of homes or green space in a community, feelings of belonging became relevant.

Choi: In the exhibition, there was few photographs, models, and drawings that introduced the completed building that is brought to mind when exhibiting architecture. The exhibition consisted of essays, statistics, collage images, and videos to reveal important issues that we should think about in the near future; there must be concerns about the relationship between message and format.

Garutti: Yes, exactly. We wanted to present the side-effects of the so-called ‘happiness agenda’ on the built environment which meant depicting space in unexpected ways. For instance, we used promotional photographs of a hotel room to enter into the story of WELL certification, a new set of criteria for interiors and buildings to satisfy beyond LEED. In that case, we were interested in how an environment can supposedly produce happiness through surface treatments, technological devices, and certain colour palettes. We were asking ourselves and the audience—‘Are our perceptions of well- being only superficial?’ With the collages by Bovenbouw Architectuur, we had asked the architects to interpret the research we had gathered and visualise the rules of conduct for a happy life found across global reports. The compositions have an ambiguous quality, simultaneously depicting textures and richness of everyday life, while flattening the city into an idealistic image, thereby capturing the contradiction in compartmentalising life into domains and indicators. We also relied on journalistic photography, social media, legal documents, and market trends to depict architectural and urban scenarios as by-products of social and economic forces, far from the field of design. The implicit question posed to architects in this approach to depicting space, therefore is ‘what is the agency of design?’

Choi: Two years later, the exhibition is now on show in Seoul HOUR under the same title. How did been this international exchange exhibition proceed?

Kim Hyoeun (Kim): When Giovanna Borasi (director, CCA) was invited to participate in the opening ceremony of Seoul HOUR in 2019, talks regarding an international exchange exhibition were already in progress and were followed up when the team from Seoul HOUR came to later visit CCA. This collaboration took shape in 2020 and we were able to organise the exhibition ‘Our Happy Life’. We wanted to unravel CCA’s curatorial framework in the Korean environment and narrate through it the story of Seoul.

Garutti: The first stage was defining a strategy to edit and fit the CCA content to the space of Seoul HOUR and developing a general structure for the exhibition. This posed a very interesting challenge and we arrived at it through a completely digital approach, with zones of distinct materiality and atmosphere for the adapted video content. Then we entered the phase of transferring the curatorial framework to the team at Seoul HOUR and the SoA, because from the start we decided that it would not be a simple touring exhibition but a dialogue and expansion of the CCA’s approach.

Kim: With SoA and Kang Yerin (professor, Seoul National University) we unpacked the specific curatorial processes and discussed them together at all stages covering the overall project direction and format, the research themes in Korea, spatial composition, public programme, and marketing solutions.

Garutti: It was an intense period of exchange and discussion, aligning perspectives and methods of representing architecture and the city and entering into each other’s social contexts. In parallel, we were developing on our side a new three-channel video essay to condense the research conducted for the original exhibition and to reflect upon the questions we generated then in light of our current crises.

Choi: Compared to the first exhibition at Montreal, what stayed the same and what didn’t?

Kim: The curatorial direction and the spatial interpretation concerning how to communicate happiness through surface, atmosphere, and mood remained the same. One might say that there were two major changes, however. First, all exhibition contents were transformed into a digital format. The 25 case studies depicting the happiness agency that were displayed in various formats such as text, image, video, exhibitions in Montreal were all communicated via video format in Seoul. We came to this decision as transportation and curator visits from CCA were restricted due to the ongoing pandamic situation. Second, the epilogue adopted a different character. At Montreal, the exhibition ended with a critical question, ‘Are the producers of rankings the new designers of our cities?’ with photos from organisations that rank cities such as The Economist, Monocle, and Gallup. In Seoul, the exhibition ends with an expanded narrative propelled by the new form of dialogue and research regarding happiness as defined in the local context.

Installation view of 'Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism', Seoul HOUR, 2021. (Image courtesy of Seoul HOUR)

Choi: How does ‘architecture’ and the ‘city’ affect people’s ‘well-being’ and ‘happiness’ in practical terms?

Garutti: Well, if I were to answer from the perspective of the Our Happy Life Report— buildings should protect people from noise or other forms of pollution, allowing 7 – 9 hours of good quality sleep. We should not have to commute too far to get to school or work. These seem like pretty basic needs. But then in the exhibition we present a suite of devices and gadgets that mediate our interiors, with commissioned photography by Yuri Pattison, examine the bond between the optimisation of rest with social demands for productivity. We explore the lives of nomadic seniors who live permanently out of Recreational Vehicles, perpetually travelling from one temporary job site to another. The critique was maybe not subtle. The influences and forces in daily lives are not operating at the architectural scales that we have assumed. That’s why I think it’s important to say that the project is also a meditation on the role of the architect today.

Choi: As part of the exhibition, interviews with architects such as Dirk Somers (principal, Bovenbouw Architectuur) and Reinier de Graaf (partner, OMA) and talks with experts from various fields were conducted and displayed. Please share some of the memorable moments in them.

Chin: Dirk Somers remarked that a straightforward visualisation of happiness would come too close to the world of publicity agencies and commercials, which is a regrettable conclusion. But as designers, they see that they can influence debates in society through images. Reinier de Graaf strongly rejected the notion that happiness can be designed, stating that architecture is about moving people and that life is about highs and lows. He finds the criteria for life and space, even if well-meaning, to be oppressive and disempowering. Mayra Madriz (director, Gehl Architects) noted that while metrics can be associated with unhealthy competition between cities under neoliberal development, they are also incredible tools to hold governments accountable. Journalist Anna Minton stressed the importance of understanding the people or institutions funding and developing such metrics and their motivations, for collective wellbeing—lower inequality is more important than individual levels of happiness.

Kim: Using his interpretation of statistical data regarding happiness and feeling, the Dirk Somers expressed an ideal and happy life and city across eight collages that used images such as the enjoyment of leisure activities close to work, the spending time together with families and friends, the co-existence of contemporary and historical buildings in an urban setting, and the seasonal and physical property of cities expressed by colours. It was very impressive to see how scientifically measured data of feelings and subjective individual happiness agenda could be assembled as a collage and expressed as something urban.

Installation view of 'Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism', Seoul HOUR, 2021. (Image courtesy of Seoul HOUR)

Choi: In the exhibition, there were city-scale research projects conducted with a focus on Tokyo, Copenhagen, and so on. The results pointed out that climate, nature, transportation, security, and other factors affect the happiness index. Also in Seoul, mountains, apartment balconies, Starbucks, and Danggeun Market ‒ things that are very familiar to Koreans ‒ are featured in the exhibition. What efforts do we have to undertake to make our lives happier?

Kim: According to SoA’s research, if one were to talk about happiness in Seoul, one should first contemplate what we should talk about as we are going through the pandemic in 2021 and how those things would impact our lives. While speaking of happiness, they also question why is it that we cannot be happy. For example, they propose the necessity of breathing space in the city through Can Breathing Matter More Than Ever? by portraying how people seek well- being within their living habitats and highlight the comfort provided by public spaces through Starbucks City while simultaneously critiquing the lack of it. In Plus & Minus of Thumbs, they express how we must also be responsible for the distribution system, the hard labour of delivery workers, and the waste that accompany happiness from the high level of comfort that we enjoy from such things. It is a situation where both the condition for and the obstruction against happiness are present, and it is my view that if these two elements were to be juxtaposed and considered as part of the city, it would be possible to discover and enjoy a greater level of happiness in Seoul.

Chin: Recognising factors such as systems help us to understand the complexity of cities and frame the space of intervention— our research showed that resilience may be designed in the detail of a sidewalk’s tree soil, equity can be distributed through a network of bikelanes, and security can be created through neighbourhood networks of care and trust. However, efforts must be made so as to not be reductive when defining problems and so as to approach them with centralised solutions. Rather than thinking and measuring factors as on a balance sheet, in terms of pluses and minuses, effort must be made to think relationally, which is to say, spatially.

Installation view of 'Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism', Seoul HOUR, 2021. (Image courtesy of Seoul HOUR)

Links

‘Our Happy Life’ (Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2019) ▶ https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/events/63178/our-happy-life

‘Our Happy Life’ (Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Architecture, 2021) ▶ https://sca.seoul.go.kr/seoulhour/site/urbanArch/exhibition/exhibitPast/441