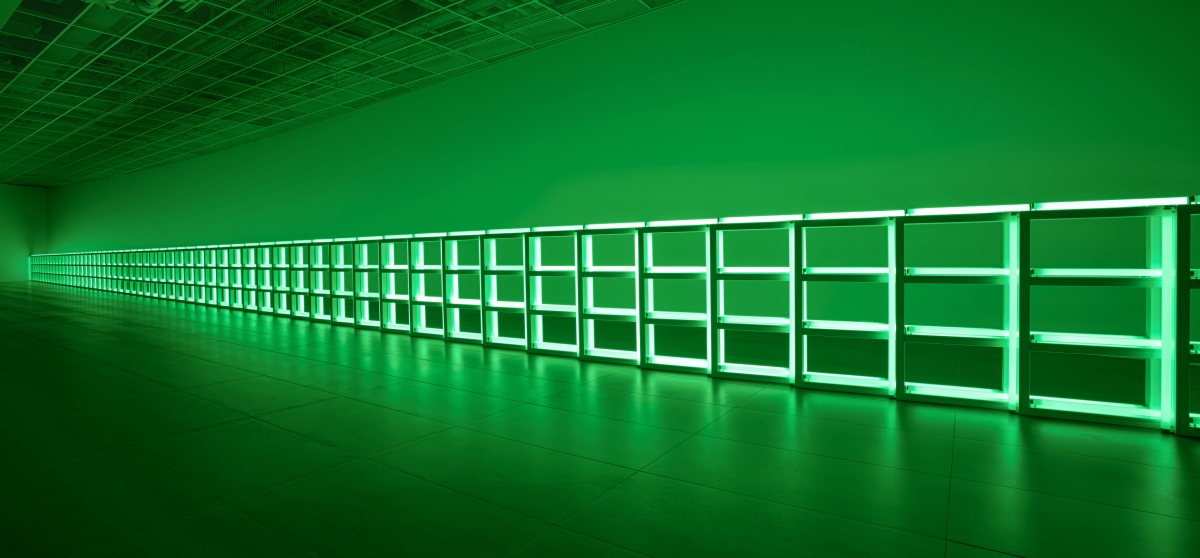

‘Dan Flavin, Light: 1963 – 1974’

Lotte Museum of Art

Jan. 26 – Apr. 8, 2018

The Crossing of Pop Art and Minimalism

The exhibition of Dan Flavin (1933–1996) begins in the showroom with alighting fixture. Before turning on the lights, his work consists of a fluorescent tube as a standardized ready-made industrial product. When the lights turn on, however, a fluorescent light seizes the spectators’ eyes with a great deal of intensity, emitting light. Lights create a metaphysical ambience in the exhibition space, and turn industrial products into materials resplendent in their existence. However, this does not mean that Flavin is fascinated by the religious implications of art. He does not like being unrealistic, overbearing, or demanding of respect. What he seeks instead is the actual space, the actual time of the present, and art with a sense of materiality. To him, art is a declaration to space, not an ambiguous set of ideas.

Dan Flavin, born in New York, is an intelligent and sensitive man who studied art history as well as fine art. In 1960, when he was 27, he had finally got his own studio in Manhattan near the Hudson River. Around this time, he filled his notebook with ideas of artworks employing electric lighting, and the results of his search over the following three years were a series of Icon. The title of Icon is drawn from Byzantine icons, comparing electro-lighting effects to the brilliance emitted by medieval icons. Fluorescent lights appear in Flavin’s work first as a series of icons. These works, which put fluorescent lights on a square box reminiscent of a canvas, recall the assemblage works of Robert Rauschenberg that combine things in interesting, different ways.

Pop and minimalism dominated the 1960s, and Flavin did not remain immune to the impact of these genres. Fluorescent lights are completely different from colours found in the natural world and are in fact very artificial. Pink or orange fluorescent lights, for example, are among so-called ‘candy colours’, which is quite a pop art colour found more easily in public restaurants and bars. As Flavin conceded, the vulgar and coarse fluorescent light of pink and yellow lamps are colours that Mies van der Rohe, the architect who pursued a more restrained modernist aesthetic, would never have used within a space.

Just as pop art represents the nature of the urban landscape in the era of mass production and mass consumption, minimalism, of the same epoch, was derived from the sophisticated and cold emotional profile of the city. When the material or structure of a work is simple, it does not necessarily correspond with the tendencies of minimalism, but rather presents the nature of an object as it is without any requisite symbolism or presence. Since Minimalist artists did not believe that a masterpiece had to be crafted by the skilled labour and due attention of an artist’s hands, not much weight was placed on manual tasks but rather on the general aesthetic of manufactured goods. So, Flavin’s employment of the common manufactured product of fluorescent light was a perfect contribution to the direction of minimalism at the time.

Dan Flavin, The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), Fluorescent light and metal fixtures, 180.3 × 177.8 × 11.4cm, 1963

The Materiality and Transcendence of Fluorescent Light

On 25 May 1963, a gold fluorescent lamp divided the wall with an oblique stroke. It was noticeably different from Flavin’s previous object works. As if to commemorate the discovery of the day, the artist dated the work: The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), a work with fluorescent lights detached from a box-like frame and placed at either side, was the active application of the non-material properties of light. From this point on, the artist did not need any additional background on which to attach fluorescent light bulbs, but only an empty wall. The entire white wall became the scope of his work, and fluorescent light was used to create diagonal lines spreading across the wall and through space.

Flavin referred to the sculptor Brancusi as the title of the work because it is associated with the work, Endless Column (1938) in a collection in Targu Jiu, Romania. The Endless Column of Brancusi consists of a layered trapezoidal wedge that expands vertically. This column is made of the same components but tries to reach infinity by repetition and connection, and to remain upright like an immortal totem. Flavin was thoroughly a city person, always had a city-oriented attitude, and the work was all set against the city. It would have been so natural for him to consider a totem as artificial, not natural. Flavin thought that his oblique stroke could be set up repeatedly on any wall and could become a totem of the modern technological world because it emitted such brilliant light.

Furthermore, for Flavin fluorescent light was a twofold material. It was neither unique nor permanent, but ready-made. There are many standardized replacements, which may no longer be manufactured one day, and these are simply inexpensive manufactured goods finite use. On the other hand, this causes an illusory experience for the viewer and sometimes prompts a kind of unexpected epiphany through connection with the light. Visions and epiphanies are illusions, which are a visionary or supernatural phenomenon beyond the material nature of things, in the nonmaterial realm.

Flavin created The Nominal Three (to William of Ockham) (1963) based on medieval philosophy as if to demonstrate the material and non-material properties of fluorescent light. In the piece, there are one, two, and three fluorescent tubes each standing vertically. A total of six fluorescent lamps have been spread out in space, emitting a pale white light. William Oakham, a fourteenth-century English philosopher and a Franciscan monk, advocated nominalism. Nominalism is a philosophical theory that explains a notion based on an entity. Ockham argued that the theoretical structure should be simple, and the variables that effect on an individual’s attributes should be minimised.For example, to recognize and apprehend red light, one must catch it through individual red objects, and its red must not be hidden by other variables. The idea of the ‘minimisation’ of variables here greatly helped Flavin to develop the concept of minimalism through his units of fluorescent light. Light is infinite and can not be counted numerically — it is difficult to comprehend simply through an appreciation of materiality. According to Ockham’s nomination theory, light is perceived as contained within an object, the fluorescent tube, and is something that can be individualised by a piece.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (to Heidi and Uwe), Fluorescent light and metal fixtures, 243.8 × 243.8 × 12.7cm, 1966-1971

(left) Dan Flavin, Untitled (to Shirley and Jason), Pink and blue fluorescent light, 243.8 × 10.2 × 25.4cm, 1969

(right) Dan Flavin, Untitled, Pink fluorescent light, 243.8 × 10.2 × 25.4cm, 1969

Monument Temporarily Lit Up

Flavin, who has researched the nature of light with his works in fluorescent light, conveys the understanding that the actual space of a room can look different depending on the positioning of a fluorescent lamp. For example, when a 2.4m long fluorescent bulb is placed at an angle on a corner, a brilliant beam of light and a shadow across both walls will blur and erase the edge of the wall to create a triangular shape. Since December 1964, Flavin has worked on the effects of light on space. Works in this period used fluorescent light bulbs on the wall at an angle to the floor and attached fluorescent light bulbs of complementary colour sat the back.

The work of Russian Constructivists in the 1920s contributed to Flavin’s idea that a wall can be a constituent part of the work, and not just a support it. Proun Rooms, in which El Lissitzky tried to organise an abstract composition using the whole room as a canvas, and the Complex Coner Relief of Vladimir Tatlin which crossed the corners of the walls with a single line, are perhaps the foremost examples. Inspired by these Russian Constructivist artists and designers, who freely used space as their canvas, Flavin was able to organise spaces through fluorescent light or to install them vertically and horizontally across corners.

The artist even used the word ‘monument’ to title this work, and most importantly, he thought to quote Tatlin's Monument to the Third International. The series Monument for V. Tatlin combines four types of white fluorescent light bulbs in a vertical or a horizontal symmetrical structure. In 1919, at Lenin’s request Tatlin made an architectural model comprising a spiral-shaped tower, in testament to the dynamic Russian vision in transformation following the Russian Revolution, but had not been built. The building inside the tower was designed to rotate 360 degrees with the help of state-of-the-art technology, and the exterior of the tower was a solid sculpture of a steel frame. Although it was only an unrealised project, it revealed the enormous potential of art to be combined with technology and to expand into architecture.

The works of the Russian avant-garde, which tried to maximise the sense of space through new materials and innovative designs, gave Flavin substantial inspiration. Citing an unrealised work by Tatlin, Flavin always put the quotation marks around the word ‘monument’. The reason for this is that the monuments he made had different characteristics. Fluorescent lights are not of eternal material like stone, but somewhat temporary. Flavin’s declaration seems to signal the decision to create a monument with fluorescent light that is destined to die out at the end of its life, a symbol of immortality.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection), fluorescent light and metal fixtures, 121.9(top) × 121.9(bottom) × 7.6cm(height) each of 58, 1973

Lee Jooeun

Lee Jooeun graduated from Seoul National University with a degree in linguistics, graduated with a master's degree in art history from the University of Denver in the United States, and subsequently received a doctorate in art history from Ewha Women's University. She was a curator at the Ewha Women's University Museum and is currently Professor of the department of Digital Culture and Contentat Konkuk University. She is also the author of a publication on art and of a serially published column on the ChosunIlbo, 'I went to the art museum', which has more than 100,000 readers.

242