One of the first things to consider when remodeling a non-exhibition space into an art gallery is the fate of the windows. Windows potentially compete with artworks as they take up wall space and attract attention, and many windows, intentionally or not, function as frames around outdoor scenes. Any decision to keep the windows as they are signals the desire to embrace the local character and historical context of the buildings seen through the windows as a part of any future exhibition. Curating an exhibition in a space, which seems to be partially yet continually occupied by a permanent installation, (whether there is an ongoing exhibition or not) can be likened to the act of attempting to draw over a half-complete picture. An exhibition space would not require windows if it displayed self-contained artefacts. In general, windows are intended to aid the experience of visitors. The earliest piloted spaceships only had windows to satisfy the human need of the astronauts confined aboard like cargo. Humans have a need for windows, to permit our gaze to wander elsewhere. This may also be why we continue to create exhibitions.

Consider how the artefacts in an exhibition have been carefully selected for display. For these objects, windows are more useful in the way they invite natural light rather than for their scenic views. As a light source, windows assist the eyes without requiring direct contact; windows are holes which furnish a given space with light. An important part of designing a museum involves creating pathways for light that do not intrude upon lines of sight, as well as controlling the overall balance in lighting by complementing the levels of natural light with artificial light. Ideally, the exhibition space must seem to have been lit up from within, yet not in such a ways as to portray the space as an exhibited artefact in itself. This is not simply an issue concerning the intensity of the light. For example, the central hall of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Gwacheon, is not that bright, yet, beneath the circular skylight through which sunlight streams, a monumental space evocative of a celestial sphere is composed through a sequence of sparkling lights and narrow windows following a spiraling pathway. The radial light falling from above, and the movement which rises to meet it, suffuses the museum with a sense of longing for the sacred.

On the other hand, the Seoul MMCA, built after the Gwacheon MMCA, is choreographed with lighting diffused throughout ground level, rather than light falling from the sky above. Light is generally absorbed by the walls and ceiling of spaces receptive to natural light, with dramatic shadowing effects minimised by artificial lighting that evenly diffuses the light. While different chambers can be reconfigured as bright or dark, tall or low, as required, no symbolic meaning is attributed to these sliding qualities. Here, the museum is portrayed as more of a congress for the arts, advocating exchange between diverse practices and objects, rather than as a pantheon aspiring to the next level. As a horizontal platform, the museum is already sufficiently open without requiring more windows. However, such openness presumes that the objects chosen for display in each chamber remain confined and do not intrude upon nor flow over onto each other. The movement of people and objects, light and air is regulated imperceptibly. Apart from the physical walls in the museum, through which opacity is controlled, undetectable partitions delineate the interior and exterior spaces of the museum, its centre and its peripheral reaches.

Walls are not negative in and of themselves, yet neither are they neutral. Walls define the space inside and out, protecting a space and its identity from what lies outside. Art museums are spaces enclosed by walls for whatever must be defended in the name of the arts. The museum has traditionally been, and will continue to be, a place in which to gather and revive the legacies of other worlds diverging from our here and now, lest they scatter. If this may permit the present to be understood as unfamiliar for some, or as offering the potential for an autonomous order free from reality to be witnessed by others, then all of these discoveries have functioned as a roadmap to remind each individual of their ability to move towards another place and time. Perhaps, it is memories such as these that inform the imaginings museums extract from their possessions. The day in which a physical museum will match with one’s ideals is at an infinite distance. Nevertheless, this extraordinary space provides us with an outlet, allowing us to outline the form of a window opening out to another place, even while we live in a world that constantly makes us feel out of place.

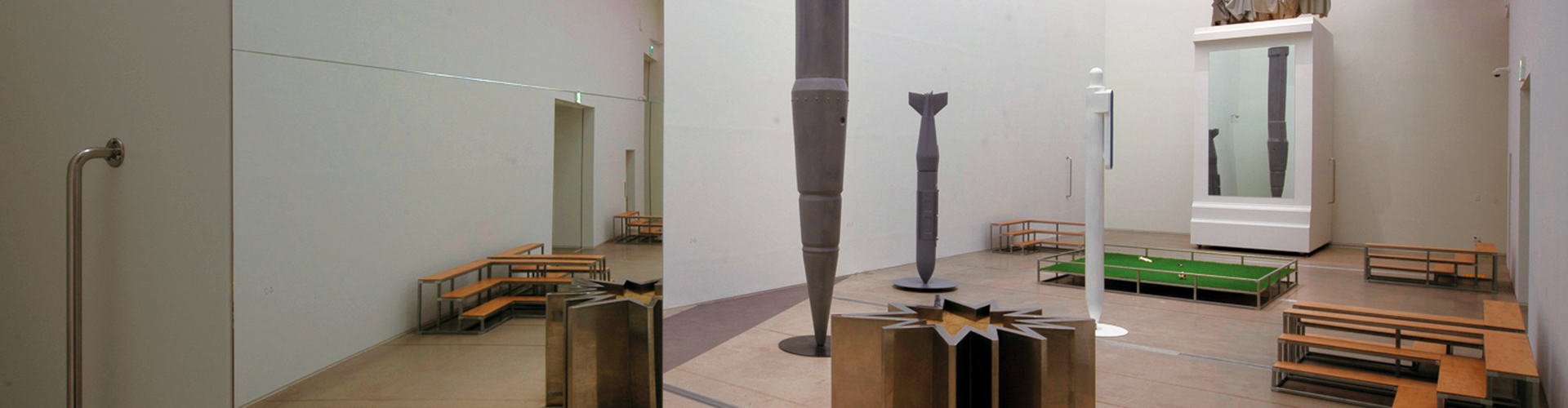

A window is not a door, and so it cannot be used to cross over to another side. On the contrary, the presence of a window indicates the existence of a wall. In this case, how might we insert windows into the unseen walls of a museum? As an example, Minae Kim diffuses light or installs reflective surfaces in exhibition halls to create imitations of windows. These things, together with other objects mimicking a museum’s typical architectural elements, temporarily distort the space, questioning what must be seen and unseen in an exhibition hall and how those boundaries might be drawn. Recently, as part of the exhibition for the 2020 Korea Artist Prize exhibition, Kim installed different objects, mirrors and fake windows to physically reflect the museum spaces in the tall and long exhibition hall that continue from underground to the upper levels of MMCA Seoul. These objects led me to come face to face with, for the first time, the ‘laylights’ of the museum. Risking stating the obvious, a museum neither lights itself up nor is it a self-fulfilling object. Light is drawn into the museum by the many objects and people who are at work out of public view.

What is the nature of this light? The mock-window installations seem to point to the exhibition’s source of light and acknowledge ‘The real light comes from outside, I’m actually a fake’. Yet, the real light, filtered through the skylights and replenishing the space in a soft manner, is of a different character to the sunlight experienced outside, which attacks the eyes and heats our bodies. These mock windows are not simply ‘almost windows’; they allude to the museum’s assumed role of hypothetical ‘manmade windows’. All exhibitions require lighting for their work to be seen, yet these mock windows light up an exhibition space by replicating the hypothetical ‘light’ that an exhibition is thought to represent. This light, according to the aesthetic tradition, derives from the place in which we must rightfully fulfill our destinies, in the sense that we are freed in the union of self and essence. A mock window signals that this ‘light’ lies at the other side of this wall. Like an ironic traffic sign, this light shines on, directing itself towards neither outside nor inside, but rather towards a narrow crevice which lies between a place which does not exist and a place which does not really need to exist. Is this place emblematic of a final remnant of hope, or of a curse that can never be undone?

Gallery 2 of MMCA Seoul. Exhibition view of Kim Minaeʼs ‘1. Hello 2. Helloʼ (‘Korea Artist Prize 2020ʼ) / Image courtesy of MMCA