In November 2020, Sung Hong Kim who has throughout his career patiently developed a study on the history of the formation process in Seoul, published his new book Seoul Solutions. Offering deep insights, the book covers various themes across the creative processes of urban architecture, such as land, law, institutions, administration, time, cost, space, and morphological structures. SPACE interviewed him to hear more about the key messages he hopes to convey through his wide-ranging and rigorous research.

Sung Hong Kim (professor, University of Seoul) x Bang Yukyung

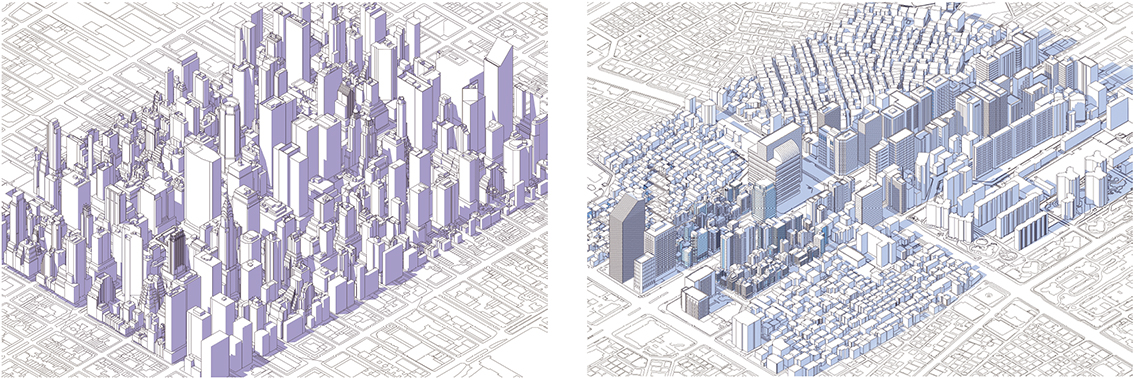

(left) Isometric of Manhattan, running north-south along Park Avenue, 39-55 Streets, east-west along 3-5 Avenues (student work). Sung Hong Kim, Seoul Solutions, p. 66

(right) Isometric of Teheran-ro, between Yeoksam Station and Seolleung Station (student work). Sung Hong Kim, Seoul Solutions, p. 67

Bang Yukyung (Bang): Your third book came out nine years after the publication of New Imagination of Urban Architecture (2009) and Street Corner Architecture (2012). What story did you hope to add?

Sung Hong Kim (Kim): I wrote my first book to point to signal cities in the east and west and the the driving principles behind their architecture when I began studying in Seoul around 2000, and the second book was to present an easy impression of Seoul while maintaining the same critical framework as the first book. Afterwards, I decided to author a book solely about Seoul with all western theories and principles removed. Oeuvres by famous Korean architects are made available in other countries. However, I wrote the book mainly as there was no proper academic research on the historical and urban context behind the creation of Seoul for foreign architects and researchers trying to understand Seoul. That is why I have consistently published a number of research papers on Seoul over time in overseas journals since 2012. I was also invited abroad to give lectures and their reactions deepened my convictions.

Bang: You carried out a lot of work during the nine years in which you wrote your books. I think that the range of your experiences, as a professor and exhibition curator, influenced your book. In particular, ‘The FAR Game: Constraints Sparking Creativity’ (hereinafter The FAR Game), the Korean Pavilion at the 15th Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibition (2016) on which you worked as artistic director, made a big splash abroad.

Kim: ‘The FAR Game’ encouraged me to write about Seoul. While preparing for the Biennale, I thought that the time of introducing well-made Korean architecture to the world is over. It is nothing but the level of a school arts festival. In the end, the biennale focuses on how sharp and creative a perspective on common problems is and how contemporary architects are contending with challenges such as environment, climate, urban inequality, polarisation, sustainability, and gentrification. In that respect, it seems that viewing Seoul, a metropolitan city with concentrated capital from the perspective of a floor area ratio (FAR) was a fresh shock. Of course, there was criticism for seeing architecture only in terms of quantitative figures. However, it will only come to a standstill if unaccompanied by figures in the capitalist market.

Bang: Seoul Solutions is an extension of that perspective. It deals in depth with the conflict and confrontation between the external logic acting on a city and the internal logic of creating buildings. In particular, analysis that traces the relationship of laws, institutions, and capitalism by regions and times distinguishes the book from others that interpret Seoul.

Kim: A large part of the book reflects experience gleaned from urbanism and the architecture related committee of Seoul Metropolitan Government from 2013 to 2014 and 2017 to 2019. My great teacher in many deliberations and evaluations was Lee Kwanghwan (principal of Stategic Planning Division, HAEAHN Architecture, Inc.), an expert in law. In fact, a city is comprised of matters of law and institutions, but I felt keenly that architects are often ignorant about this union. It is not that there were no experts in the field who understood these things, but they simply could not explain their knowledge in a language that people could understand. They know how the Act on the Improvement of Urban Areas and Residential Environments operates on a construction site, but they find it difficult to explain in plain words. I felt that someone should interpret this properly, and so I tried to explain how urban architecture has been formed and changed by laws and institutions in this book.

Bang: Seoul is still changing under the shifting framework of the law, systems, and administrative bodies. What for you are the issues facing the architectural world now, and to which architects should attend?

Kim: The average parcel area in Seoul is 250m2. Compared to this, the parcel area of most large-scale redevelopment, reconstruction, and urban environment rearrangement projects ranges from 10,000 to 100,000m2 or more. They are created not through the Building Act, but through the Housing Act, Urban Improvement Act, and under various District Unit Plans. There is no room for medium-sized architectural structures in between. In the end, is it not the interface between the city and architecture with which architects should deal? Aren’t the spaces created in this kind of interface so-called ‘publicity’? Recently, medium-sized projects such as the Block-unit Housing Rearrangement Project and Autonomous Housing Improvement Projects are carried out, but the system still makes architects carry out projects within a framework created by urban engineers. It is a pity that the places in which our cities are rapidly changing are out of reach to architects.

Bang: I think that the Seoul public architect and Seoul village architect system and the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy were established in the hope of playing a significant role.

Kim: Of course, they were expected to do so, but the reality was different. The working scope afforded to architects is extremely limited within the administration of Seoul and the municipality. They can participate in design competitions of public facilities on a plot, but the Master Architect is completely excluded from any involvement in urban management planning, urban master plans, district unit plans, and urban improvement projects. The real problem is that even if architects are allowed to participate in the project, they canʼt communicate with others. Architects must understand the language of urbanism; if architects learn it, they can find out where the detonator of urban issues are and communicate with urban engineers instead of facing off with them. In the same context, the underlying reason why architects cannot participate in construction is due to their lack of capacity to control details in the construction process compared to construction companies.

Works from the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2016,

Bang: Part 4 of this book, ‘Proposition’ was written based on real experience as a teacher at the chalkface. How should one teach the law and its corroborative systems to students in order to improve their understanding and overall awareness?

Kim: It may sound ironic, but I do not think laws should be taught in detail at college.

I believe that architecture should be created according to its own rules, even without external conditions. Only then can students keep and develop their own architecture under external influences and pressure when they practice in the field. Design education should be further strengthened at school so that they can build upon an inner logic. I reject design education that provides a specific sites, concrete forms, and conditions and solves design from the outside to inside. Universities should approach architecture in a different way to those working in the field. Otherwise, they will be nothing but vocational schools.

Bang: How does the content of this book relate to architecture education?

Kim: It will not be possible to apply all of the content to a pedagogical context. Even if students donʼt know the details of laws and regulations, I hope they will come to understand when they graduate from university that architecture is the product of a constant conflict and clash with external forces that surround its inner principles. Developing graduation works, some students design a museum with a FAR of 200% on a site with a FAR of 600 ‒ 800% in a city centre. I mean I wish they had a rough idea about who owns the land, private or public; how to purchase the site and how much it will cost; the volume required to offset the cost. I think it would be best to read this book in the second semester of the fifth grade.

Bang: In that sense, the expression ‘sandwiched architect’ in reference to contemporary architects resonates with me. How has it become possible to create and expand the position of architects beyond realistic constraints?

Kim: Urban planning, if compared to other activities, is an important task that draws on social agreements, provides procedures, and transforms them into a broader framework for institutions and guidelines. On the other hand, architects design physical entities based on their creative powers. They should provide specific answers rather than the fictional or imaginative. Employing creativity to solve issues is a great advantage unique to architects. When architects see a city, they consider it to be a realistic object, rather than the object restricted by laws and institutions. They see its materials and its spaces. Architects can become urban planners or engineers, but the reverse is not true, and so I think architects have greater potential.

Bang: You finish the stories of urban architecture in three books. Are you preparing any other publications?

Kim: I think Iʼm going to write a story about architecture that envisions an independent autonomy. In fact, isnʼt that the core concern of architects? I mentioned few Korean architects in this book, except for two people: Suh Jaewon (principal, aoa architects) and Lee Dongjoon (co-principal, Stocker Lee Architetti). I found pure geometric spatial norms in their architecture. The ability to orchestrate sections that correspond with urban constraints to form geometrically refined plans. The representative example of a holistic form is the plans behind historic buildings in Paris or Rome. The periphery of the building conforms to an atypical urban context, but the central part retains a perfect geometry. Ironically, however, both explain their works through grounded conditions such as ‘FAR’ and ‘regulations’, and not with a meta-discourse such as philosophical musings or creative principles. They don’t have to mention such things because they have a self-integrated grammar that blends their concepts and their architecture. This elevates their works above the eclectic buildings around them, which rely upon gratuitous curves and diagonal lines at the expense of the site context.

Bang: What do you think will become important in terms of the changes you anticipate in Korean architecture, including for that of young architects?

Kim: Architects will have to become real experts. In that sense, I find hope in fourth-generation Korean architects. Hundreds of foreign-schooled architects are returning home, and they are competing on the same stage as overseas architects. Eventually, the quality of the final product, that is, of the structure rather than the meta-discourse, will ultimately determine victory or defeat. I believe that the extent to which an architect can take control of a site and its details will continue to be an important point of differentiation with the architect.

Urban Tattoo: signbords of Miju Shopping Center (student work). Sung Hong Kim, Seoul Solutions, pp. 208 - 209. ⓒ Han Juhee