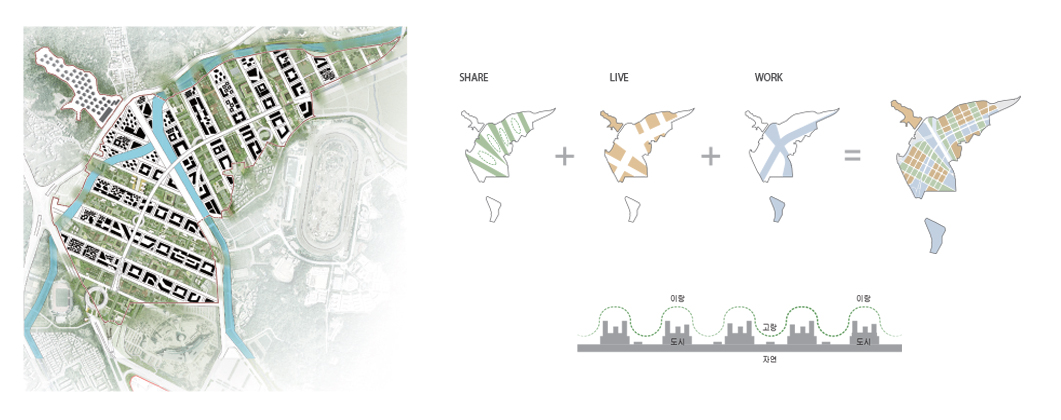

Gwacheon-Gwacheon, Layout shown the concept of ridges and furrows ⓒ SIAPLAN Consortium

ROUNDTABLE

Kee Hyosung (chairman, Urban-Lab Cooperative, director, Han-A Urban Research Institute)

Kim Saehoon (professor, Seoul National University)

Lee Jaeseung (professor, Seoul National University)

Jung Sanghoon (professor, Gachon University)

Hwang Gayeon (manager, Urban-Lab Cooperative)

Kim Saehoon (Kim): Recently, a rough sketch of the basic design for the 3rd Generation New Towns was publicised. The President Moon Jae-in administration announced their Policy of Providing 300,000 Houses in the Metropolitan area in order to stabilise the housing market. These include the five different districts that have been designated as 3rd Generation New Towns: Wangsuk-Namyangju, Gyosan-Hanam, Changneung-Goyang, Daejang-Bucheon, and Gyeyang-Incheon; and public housing districts: Gwacheon-Gwacheon and Jangsang-Ansan. In general, what do you think of the location, size, and defining characteristics of the 3rd Generation New Towns?

Kee Hyosung (Kee): In terms of their location

and size, the 3rd Generation New Towns are different from the previous New Towns.

First, it broke the unwritten law behind previous New Towns projects – that they

would not encroach upon Green Belt land – by releasing large swathes of the

Green Belt. Of course, it mostly released areas that had been determined to be

third grade or less and of low conservation value. It must have been a decision

made when searching for easily accessible sites within 20km from the centre of

Seoul. In terms of their size, when compared to the previous developments that consisted

of more than a 3-million-pyeong (about 991,735㎡), the 3rd

Generation New Towns are to be developed on a smaller scale. Since they are close

to Seoul and their surface areas, populations, and number of businesses is

relatively small, it will be challenging to implement the proposed aims of

including the ‘creation of jobs’ and ‘pursuit of self-sufficiency’. In terms of the

system, the 3rd Generation New Towns are based on the Special Act on the

Construction of Public Housing, which was revised based upon the Act on the

Special Measures for the Construction of National Rental Housing and the

Special Act on the Construction of Bogeumjari Housing. Accordingly, more than

50% of all housing is public housing, of which more than 35% is public rental

housing and less than 25% is public tract housing. Whereas the previous New

Towns were cities that had mainly 30-pyeong (about 99㎡)

private housing units, the 3rd Generation New Towns are cities of mainly

20-pyeong (about 66㎡) public housing developments.

Kim: Let’s take a look at the design competition

for the basic design of the new towns. Interestingly, the competition guidelines

presented the proposal topics and development directions for each site in a

very specific manner. For example, in the case of Gwacheon-Gwacheon, the

guidelines outlined the governing theme of a ‘street-oriented shared city’ with a plan for land use, area tables, and planning principles.

Going one step further, it also included additional requests such as to ‘avoid

super blocks and to compose small and medium-sized blocks’ and to ‘use a linear

arrangement of mid to low-rises along the street to encircle the overall

design’. Moreover, in addition to the basic design, it requested a proposal for

the ‘Integrated Master Plan for Urban and Architecture’ as mandatory to

submission. Through these actions, the competition designated specialised zones

within the new towns and requested the establishment of not only

two-dimensional plan designs but also three-dimensional spatial plans.

(left) Wangsuk2-Namyangju, Wangsuk-type Courtyard ⓒ G.S Architects Consortium

(right) Gyeyang-Incheon, P-PATH (Park Path) ⓒ Siteplanning Consortium

Hwang Gayeon (Hwang): The fact that the

competition guidelines were specified in such detail means that the host

pondered them greatly in the preliminary stages of their preparations. From the

perspective of a person who participated in a competition, providing specific

guidelines at the early stages of designing a new town of multiple functions

and demands may inhibit freer thinking. The winners must have felt similarly.

As an example, following the guidelines, most of the winning proposals were

designs of small blocks of 60 × 90m modules and courtyard housings. In urban planning,

the process of selecting a particular block size and housing type is extremely important,

but in fact, it was difficult to find an explanation of why the size of the

block should be so small and why the housing units had feature a courtyard.

Jung Sanghoon (Jung): I agree. If the location

already had enough of an urban atmosphere, a small block encouraging contact

between the city and its occupants is more appealing. However, it takes a long time

for a new town to become urbanised after its construction. Moreover, those who

settle in the new town in the first place wish to enjoy a relaxing natural environment

and a rural life with a certain level of urban vitality. In this case, a super block

rather has merit. This is because once a large expanse of land uninterrupted by

roads has been secured, then it is possible to jointly purchase park land,

green areas and open spaces at a reasonable cost.

Lee Jaeseung (Lee): The effort to improve and

standardise the landscapes of the existing new towns through this competition

should be very highly commended. As a result, in the future, it will be

necessary to revisit what the design competitions of the basic design for the

new towns achieved. Should it not be a public project promoter, such as Korea

Land & Housing Corporation (LH), who is the principal agent in initiating competitions

and steering the process of creating new towns, to select a design entry that

can be applied to the public sector – such as urban structures,

infrastructures, public lands, schools, and parks – rather than the private

sector? A design for the private sector that is nicely presented from a given

perspective is, in fact, for areas in which the public cannot guarantee its implementation,

except for areas that can be regulated by district unit plans such as development

scale and construction lines.

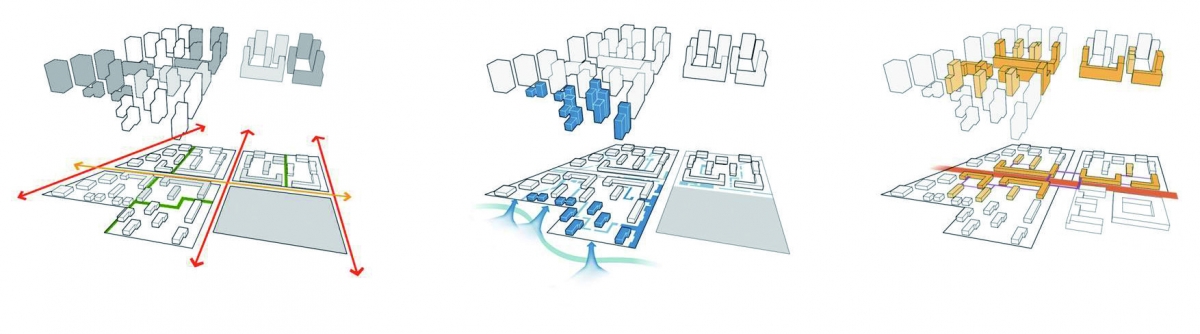

Kim: An urban design competition is different

from an architectural design competition, in that an urban design competition

is difficult to establish a 1:1 corresponding relationship between a single concept

and a single form. Let’s talk about the city’s governing concept. In the case of

Wangsuk-Namyangju, the proposed idea was that of a ‘Symbiosis City’, and as the

content of symbiosis, a city of ‘multi-persona’ was presented. However, it was actually difficult to identify the

subject of this persona, how this new town would be different from other new

towns, and how such symbiosis could be transferred to the spatial design. In

contrast, in the case of Gwacheon-Gwacheon, at least I have a high opinion of

the fact that the concept was expressed in a clear spatial vocabulary. I think

it was good decision to compose the urban form through two different types of

band: a linear type where highly-dense developments will take place following the

concepts of ‘ridges and furrows’, and a type of a shared zone which will be

used as parks, green areas and community spaces.

(left) Wangsuk-Namyangju, Specialized planning area ⓒ DA GROUP Consortium

(right) Wangsuk2-Namyangju, Specialized area where the three streams meet ⓒ G.S Architects Consortium

Jung: I personally think a good city is a city that realises a good concept through a highly legible structure. For this reason, it is necessary to have an in-depth discussion of the true nature and the meaning of the urban concept, and on urban structure itself. In terms of the pedestrian environment, there is a lot left to be desired in setting the public-transportation-oriented-pedestrian axis, a spatial sense of encirclement, and establishing the function of the first floor surrounding it. It would not have been easy to resolve this well within the short term of the competition.

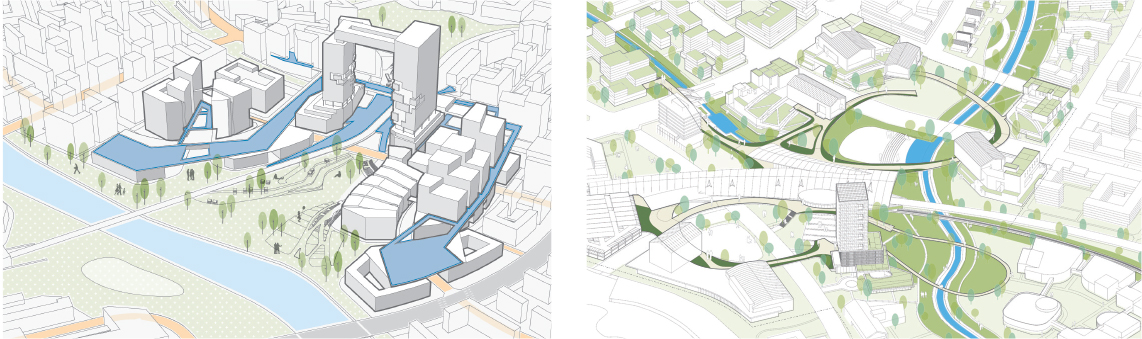

Kee: Of the winning proposals, I think the urban

concept of the ‘Eco-Sponge’ proposed for Changneung-Goyang was the best one implemented

within the space. The junction between Mangwol Mountain, the river, and the

city was imagined as an ecotype reservoir while also ensuring it would be used

more ordinarily as Dulle-gil. In the Wangsuk2-Namyangju, after identifying the distribution

of the furniture manufacturing industry – which is deeply connected to the industrial

character of the surrounding area – nearby, the design

aimed to introduce a function of life and cultural design industry in the new

town. I liked that this was realised as the Dumulmeori Square and an Art Center

at which three streams meet. When an urban concept bonds to its local status

and natural conditions, it becomes more powerful.

Kim: I am also curious about your impression

of the metropolitan and public transportation project proposed by the winning

proposals. In general, the design established transportation hubs such as GTX

and S-BRT to act as specialised areas and to emphasise a sense of traffic-friendliness,

with subways and bus stops provided within a 10-minute walk from anywhere in

the new towns increase access to public transportation.

Kee: Access to transportation is extremely important

in a new town. However, considering the short term of the competition and the

identities of the participants, I feel like the objectives of these

competitions ask too much of their contestants. Due to the weight of these expectations,

several winning proposals presented a lot of untested plans for transportation.

For instance, in the design of the Wangsuk2-Namyangju, a regional highway was

presented to Gyeongchun-ro as a six-lane road, with a bus-only lane in the centre followed

by a lane for general vehicles and an outermost lane for self-driving vehicles.

Considering the overall traffic flow, a single one-way lane for general

vehicles is difficult to imagine.

Gyosan-Hanam, Urban Plateau ⓒ GYEONG GAN Consortium

Lee: I believe the ‘traffic-friendliness’ requested

in the guidelines of the competitions is not necessarily an issue for the

transportation system. In terms of qualitative aspects, it is important to

consider the mobility handicapped, the balance of needs posed by pedestrians/bicycles/single

drivers, the speed restrictions on highways and side streets, and the

development of small-scale parking lots scattered throughout, in order to

create a ‘traffic-friendly’ city.

Kim: It is also worth noting that the guidelines

stressed the ‘three-dimensional planning of urban space’ and the ‘mixing of

different classes and generations’. In the winning entry from Gyosan-Hanam, an enlarged

structure resembling the earth’s surface named the ‘Urban Plateau’ covers the Jungbu

Expressway and the Meeting Plaza. I rate the spatial language that resuscitates

a disconnected urban fabric occasioned by large-scale highways very highly.

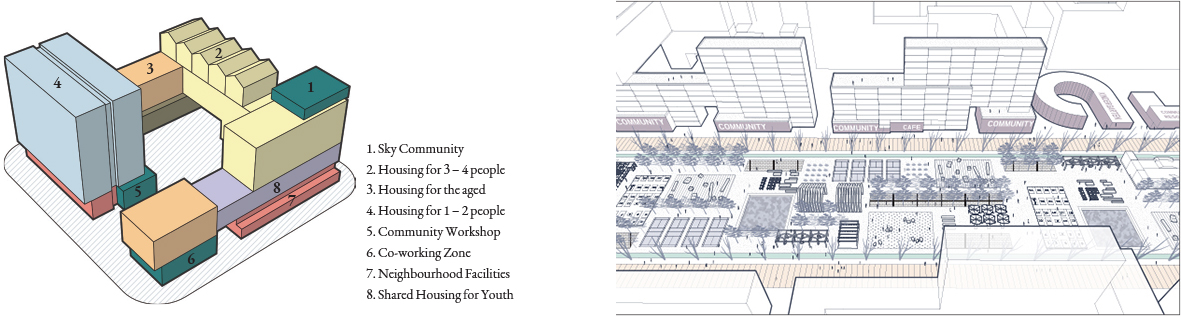

Jung: I agree with the purpose of mixing different

classes and generations. However, although the ‘Wangsuk-type Courtyard’, suggested

in the winning entry for the Wangsuk2-Namyangju, was a novel attempt, it had to

be adjusted. Housing for 1 – 2 individuals, housing for seniors, private tract

housing, and rental housing do not have to be located in the same block around a

single courtyard as intermediation. It would be better to implement an approach

that would provide a place to encourage interaction . Furthermore, it is

questionable whether there are businesses in Korea that are able to develop and

run such complex housing types on a single site.

Kim: There were other important keywords signalled

by these competitions for the new towns, including economic self-sufficiency and

the creation of jobs. In the earlier 1st and 2nd Generation New Towns different

attempts were made, including inviting large-scale sales facilities and

business facilities and relocating administrative and employment facilities

from other cities.

Kee: When the 3rd Generation New Towns were

announced, the total area of the self-sufficient site proposed by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure,

and Transport (MOLIT) was 13 times larger than the area of the Pangyo Techno

Valley. This implied that a large proportion of the site will serve the

metropolitan area. I presume that it will be difficult to fulfill those supply

demands. This prompted another concern: what kind of companies, roles or

functions will fill the area? The winning proposals suggested mixed-use sites

in order to secure self-sufficiency, but in fact, a highly advanced level of mixed-use is

already feasible in the commercial sites or peripheral city regions in the

existing new towns. Something that differentiates the mixed-use site proposed by

the winning proposals from that of the existing new towns is that the new enables

residential functions—however, it is doubtful whether this will help to strengthen

a notion of self-sufficiency.

Hwang: In terms of the urban environment, it

is impressive to have secured a high percentage of park land and green areas within

these 3rd Generation New Towns. However, on the contrary, it indicates that the

percentage of land that will be supplied for free is high, so in the end, the public

project promoter will eventually adjust their design plans in the direction of expanding

the provisional disposal site in a good location, which can be sold to the private

sector. Throughout this process, the initial intentions driving many commercial

sites and self-sufficient sites may become distorted. The goal and

appropriateness of developing self-sufficient functions in a given city must be

carefully considered along with the location and size of the city.

Goryang Changneung, Eco-sponge ⓒ HAEANN Architecture Consortium

Kim: Finally, please outline the

significance of the competition for the 3rd Generation New Towns and the

meaning that runs through these different winning proposals.

Lee: What I rate most highly in these competitions

is that there has been a slight change to the format of urban design. The previous

process of designing new towns was led by a large construction engineering company

and operated in a rather closed manner. In these competitions for the 3rd Generation

New Towns, there was a balance between cities, architecture, and landscape in

terms of the contestants and formation of the reviewing committee, and the

promotion process has changed to adopt a more open manner. It was also a

admirable gesture by MOLIT to introduce an Urban Concept Planner before the

competition was held, and to conduct a preliminary review of each site. From

now on, I hope that experts from across various fields will collaborate more closely,

settling these spaces into a system that is able to create a truly great new

town.

Kee: Earlier, we discussed an imbalance between

the demand and supply to the self-sufficient site and the creation of jobs in the 3rd Generation New

Towns. Before the announcement of a basic design, there should be an integrated

research project conducted on the core site and its grounds. Design entrants

only study the individual site, so there is no time to figure out the bigger

picture. In terms of the site area, size, number of businesses and employees,

if there is solid basic data set from which plans can will be developed in the

future and shared along with a basic design proposal, more promising design

entries can be submitted.

Jung: It is necessary to select and focus upon

what we want to obtain through the competition for the new towns. I wish the

purpose of these competitions were more clear, for instance, whether they

expect to see entries that can truly be realised as originally designed or if

they want to receive the overall philosophical and urban concept serving as the

basis for directions to be studied in the future.

Hwang: It was good to see these competitions

draw sufficient attention to radical social issues such as super blocks, white

zoning, self-sufficiency, parks and green spaces, transportation challenges, and

logistics and. Aside from this, I am excited to see that small but meaningful cities

that are closed to Seoul, of mainly 20-pyeong housing units and in which young

people live and work, being created.

Bucheon Daegang, The first village near Lake Park ⓒ DA Architects Office consortium

Kim Saehoon graduated from the Architecture Department at Seoul National University and Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is associate professor at Seoul National University Graduate School of Environmental Studies. He is co-running the Urban Studies and Design Lab and authored a book titled Exploring the City Through Cities (Hansup, 2017).

Lee Jaeseung received his Ph.D in planning from MIT. He is associate professor at Seoul National University Graduate School of Environmental Studies. His research and practice focus on reciprocal interaction between urban environments, human behaviour, and quality of life.

Jung Sanghoon graduated from the Department of Civil, Urban and Environmental Engineering at Seoul National University and Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is associate professor at the Department of Urban Planning and Landscape Architecture at Gachon University. He runs the Urban Innovation Lab and has authored multiple papers on urban development and urban design.

Hwang Gayeon graduated from the Department of Urban Design at Hongik University and Seoul National University. She is an urban designer at the Han-A Urban Research Institute and the Urban-Lab Cooperative.